Mary J. Reed, PhD, APN, PMHCNS-BC On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify key physiologic, psychologic, and sociologic changes associated with aging that make it difficult to identify and treat substance abuse in older adults. 2. List the key components of assessing older adults for substance abuse. 3. Identify the key multidisciplinary and nursing interventions for older adults who abuse substances. 4. Identify the signs and symptoms of alcohol abuse and withdrawal in older adults, and describe the corresponding nursing interventions. 5. Identify the signs and symptoms of prescription medication abuse and withdrawal in older adults, and describe the corresponding nursing interventions. 6. Identify the signs and symptoms of nonprescription medication abuse and withdrawal in older adults, and describe the corresponding nursing interventions. 7. Identify the signs and symptoms of nicotine abuse and withdrawal in older adults, and describe the corresponding nursing interventions. 8. Identify the signs and symptoms of caffeine abuse and withdrawal in older adults, and describe the corresponding nursing interventions. The well-documented prevalence of elderly substance abuse and the aging of the baby boom generation indicate that substance abuse and its treatment will soon be one of the most pressing public health concerns. Among those aged 65 years or older, 2.36% of men and 0.38% of women in a national epidemiologic study met criteria for alcohol abuse. It is estimated that up to 11% of older women misuse prescription drugs and that the numbers of users of nonprescription drugs among older adults will increase to 2.7 million by 2020 (Trevisan, 2008). Frequently, the symptoms are subtle or atypical, or they mimic symptoms of other age-related illnesses and remain undiagnosed. Clients’ presenting symptoms may be erratic changes in affect, mood, or behavior; malnutrition; bladder and bowel incontinence; gait disturbances; and recurring falls, burns, and head trauma (Morris, 2001; Videbeck, 2004). Approximately one third of older adults began to abuse alcohol late in life because of bereavement, retirement, loneliness, or physical and emotional illnesses. Denial is more intense in older adults because of cognitive and memory problems and shame that substance abuse is immoral. Prescription drug abuse in older adults is two or three times higher than in the general population. Benzodiazepine abuse and dependence are more common than in the general population, and the drugs are usually prescribed over longer periods, which results in excessive daytime sedation, ataxia, falls and accidents, and cognitive impairments such as attention and memory problems (Fontaine, 2003). Nurses must understand definitions associated with substance abuse to correctly assess it and plan appropriate interventions for older adults. The fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) is used by physicians to aid in diagnosing clients. The DSM-IV-TR distinguishes between substance abuse and substance dependence. Substance abuse is defined as “a maladaptive pattern of substance use manifested by recurrent and significant adverse consequences related to the repeated use of substances.” Substance dependence is defined as “a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms indicating that the individual continues use of the substance despite significant substance-related problems” (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Substance dependence also comprises the distinct phases of tolerance, withdrawal, and compulsive drug-taking and drug-seeking behaviors. Box 18–1 lists the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for substance abuse and substance dependence. Substance misuse is a problem for many independent-living older adults. It includes not following instructions on a prescription by either taking too much or not enough medication or taking someone else’s prescribed drugs. Misuse also means self-medicating with old prescriptions kept long after the reason for the prescription has passed (Meiner, 1997; Meiner, 2004). It can be argued that alcohol use disorders represent one end of a continuum of problematic alcohol use. The terms hazardous use and harmful use have been used to define consumption of alcohol in amounts that are harmful or potentially harmful to physical health but that do not necessarily meet DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence. These terms are defined according to the number of drinks consumed. Measures that are based on quantity and/or frequency of alcohol consumption may more accurately describe the extent of problematic alcohol use in the elderly. Hazardous or at-risk use of alcohol is that which exceeds the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines. For adults 65 years or older, hazardous use is three or more drinks at one sitting or more than seven drinks a week. These guidelines are the same for men and women (Trevisan, 2008). The physiologic, psychologic, and sociologic changes associated with aging make the identification and treatment of substance abuse in older adult clients difficult. Most studies report that the average older person is not taking the prescribed medication at all or is taking unnecessary drugs with dosages that are too high, even though a safer alternative to the drug is available. Age-related psychologic and sociologic changes and symptoms can be subtle or atypical and can mimic symptoms of substance abuse (Mohundro & Ramsey, 2003; Videbeck, 2004). Often clinicians and family members are hesitant to ask whether the older adult is having problems with substance use or misuse of prescription medications. Traditionally accepted ways of detecting problems with substances (e.g., time lost from work, legal problems, or decreased participation in important social activities) are not helpful in older adults because they generally have fewer activities and obligations (Trevisan, 2008). Patients with early-onset alcohol dependence appear to have a more severe course of illness. They make up about two thirds of the dependent drinkers in the elderly, are predominantly male, and have more alcohol-related medical problems and psychiatric comorbidities. Patients with later onset alcohol dependence tend to have a milder clinical picture and fewer medical problems because of the shorter exposure to alcohol. They are more affluent, include more women, and are likely to begin their alcohol use after a stressful event, such as loss of a spouse, job, or home (Trevisan, 2008). Psychologic changes in older adults result primarily from the numerous losses this age group may experience in a relatively short period. Separation from family and friends, retirement, a decline in physical health, and a decreased ability to participate in previous social activities can contribute to feelings of loss. Two thirds of this age group has long-standing problems with alcohol and multiple medical complications. One third develop a drinking problem late in life, often in response to bereavement, retirement, loneliness, relationship stress, and physical illness (Eliopoulos, 2001) (Fig. 18–1). The DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance abuse are developed for the general population, not specifically for the older adult population (see Box 18–1). Therefore it is essential for the nurse to assess clients’ medical and psychologic histories. After a history is complete, the nurse should identify whether the key medical and psychologic manifestations of substance abuse are present (Boxes 18–2 and 18–3). A number of screening tools are available to assess alcohol use (Figs. 18–2 to 18–4). The two most commonly used tools are the CAGE (Mayfield, McLeod, & Hall, 1974) and the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) (Selzer, 1971). The Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (BMAST) is a modified form of the MAST (Pokorny, Miller, & Kaplan, 1972). Frederick Blow developed the MAST—Geriatric Version (MAST-G) (Morton, Jones, & Manganaro, 1996). Results indicate that the MAST-G is an instrument that is more reliable and valid in the older adult population than the MAST (Knight & Mjelde-Mossey, 1995). Even though further research is required to validate the use of these tools for the assessment of abused substances besides alcohol, positive clinical results have been demonstrated with the use of these tools, substituting the words substance or prescription medication for drink. Clients undergoing detoxification from alcohol abuse should be assessed on an ongoing basis using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment tool. The tool measures the severity of alcohol withdrawal based on 10 common signs and symptoms: nausea and vomiting; tremor; paroxysmal sweats; anxiety; agitation; tactile, auditory, and visual disturbances; headache; and orientation. The maximum score is 67, and clients who score higher than 20 should be admitted to a hospital (Fontaine, 2003). • Risk for altered body temperature • Ineffective individual coping • Altered family processes: alcoholism • Altered nutrition: less than body requirements Interventions and treatment options include brief therapy, intensive outpatient or inpatient treatment, and residential treatment. Brief therapy is usually provided by a trained professional in a community drug treatment center. Goal setting, self-monitoring, and identifying high-risk situations are specific behaviors that clients learn in order to stop or reduce their substance abuse. Intensive outpatient programs allow clients to remain at home and continue working while they participate in treatment in an unrestricted setting for 4 to 5 hours every day. Intensive inpatient treatment occurs in the emergency department or acute care inpatient units for clients at risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, for those who are psychiatrically disabled, and for those who have not responded to less intensive treatment efforts. Residential treatment programs are downsizing and closing because third-party reimbursement is rapidly decreasing. Traditionally treatment lasted 7 to 21 days and offered a safe and structured environment for those who lacked social and vocational skills and drug-free social supports to be abstinent in a less restricted setting (Fontaine, 2003).

Substance Abuse

Definitions and Common Usage

Difficulty in Identification of Abuse

Physiologic Changes

Psychologic Changes

Assessment

Substance Abuse History

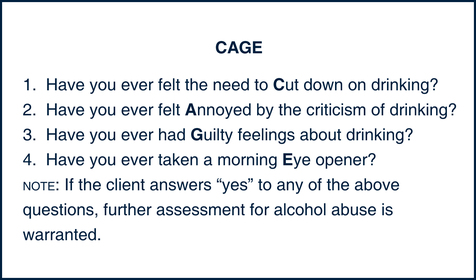

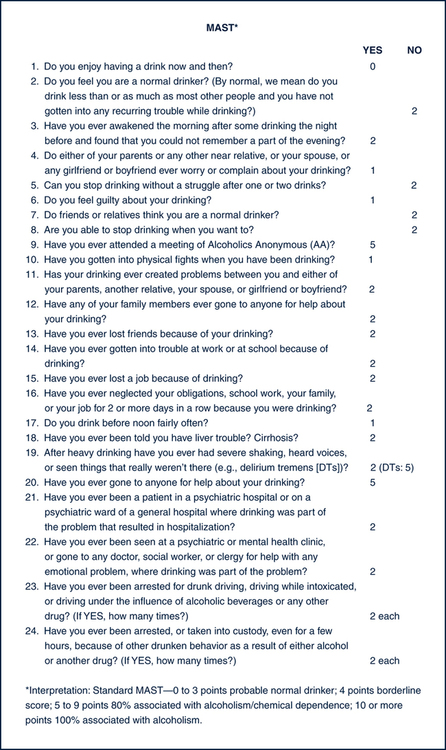

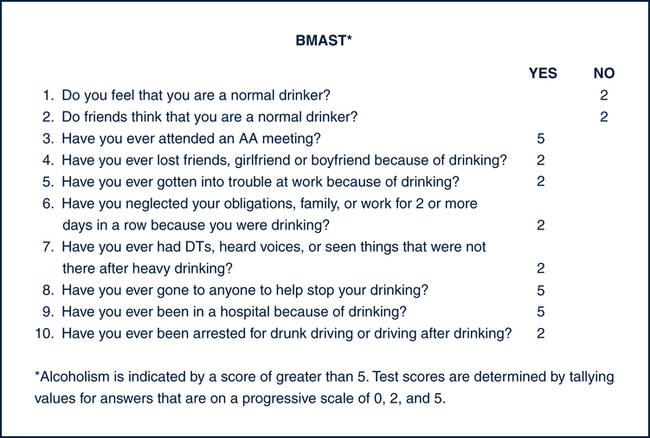

Screening Tools

Nursing Diagnoses

Interventions

Substance Abuse

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access