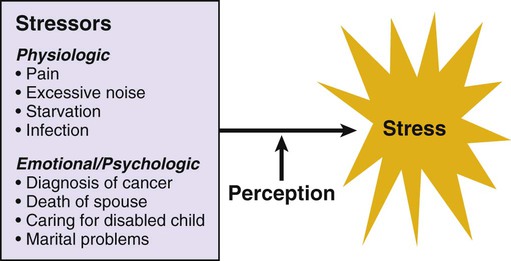

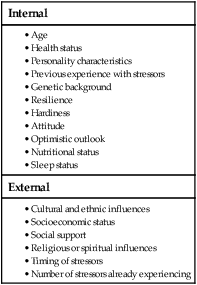

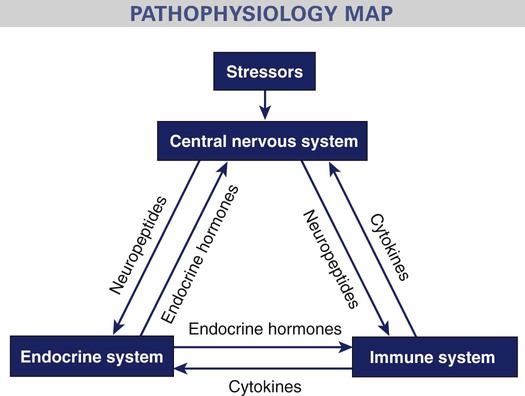

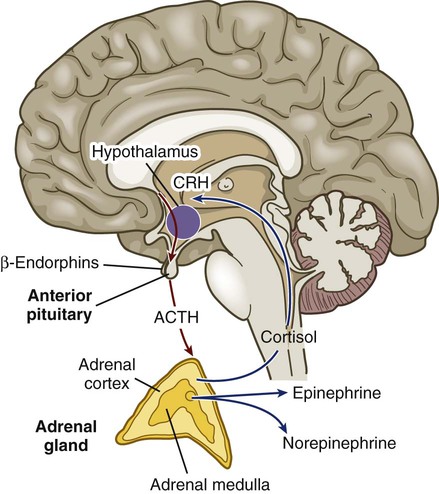

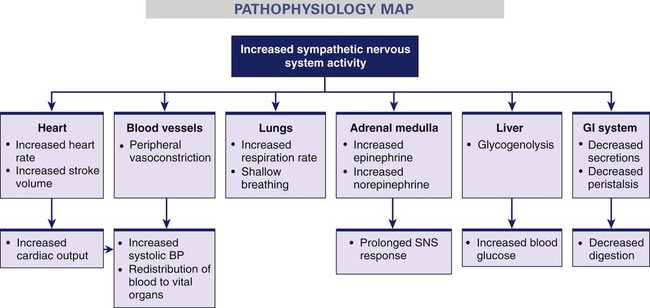

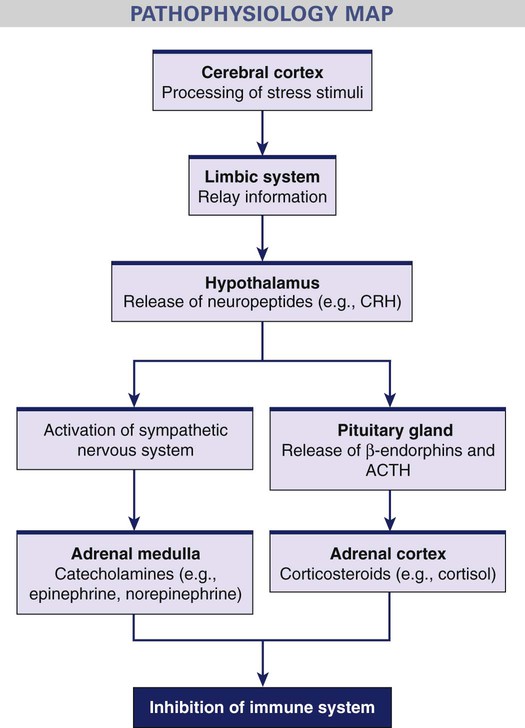

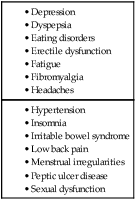

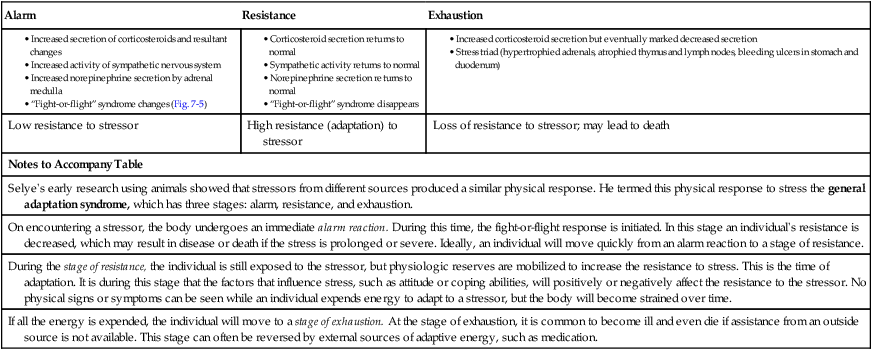

1. Differentiate between the terms stressor and stress. 2. Explain the role of coping in managing stress. 3. Describe the role of the nervous and endocrine systems in the stress process. 4. Describe the effects of stress on the immune system. 5. Discuss the effects of stress on health. 6. Describe the coping and relaxation strategies that can be used by you or a patient experiencing stress. 7. Describe the nursing assessment and management of a patient experiencing stress. Stress is the inability to cope with perceived (real or imagined) demands or threats to one’s mental, emotional, or spiritual well-being.1 Because demands are perceived differently based on the person and situation, what is emotionally or psychologically stressful to one person may not be stressful to another. Individual responses to the same stressor vary greatly. Perception of the potential stressor influences the way an individual responds to that stressor (Fig. 7-1). This is demonstrated in the following examples. • B.J., a 43-year-old woman, becomes depressed after a laparoscopic hysterectomy for fibroids. She is unwilling to participate in normal self-care activities. You are surprised by her response and think that this is fairly simple surgery and she should get on with her life. After further assessment, you discover that the removal of her uterus is a great psychologic stressor because she perceives it as a loss of her womanhood and femininity. • K.R., a 52-year-old woman, has just been told by her physician of her new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. After the physician’s visit to her, you are prepared to provide emotional support. However, you are puzzled when she is smiling and breathing a sigh of relief. You think that this diagnosis should be stressful. However, K.R. tells you that she is so relieved because for weeks she has worried that her symptoms were related to terminal cancer. Many different events or factors can be stressors. They can be physiologic or emotional/psychologic (see Fig. 7-1). The emotional/psychologic stressors can be positive or negative. For example, the birth of a baby is a positive stressor. Marital discord is a negative stressor. eTABLE 7-1 STAGES OF THE GENERAL ADAPTATION SYNDROME The key aspect of stressors is that they require an individual to adapt. In addition, differences in the behavioral and physiologic adaptive responses to a stressor can be based on the duration of a stressor (acute or chronic) and intensity of a stressor (mild, moderate, or severe). For example, an individual dealing with the chronic stress of caring for a loved one may also be exposed to many acute episodic stressors (e.g., car accident, influenza). Therefore the type, duration, and intensity of a stressor are important variables that can influence an individual’s adaptive response (Fig. 7-2). Why do people respond so differently to stress? Why do some people cope better with stress than others? Interestingly, some individuals experience significant adverse life events but do not succumb to the effects of stress. Factors that affect an individual’s response to stress include internal and external influences (Table 7-1). These factors indicate the importance of using a holistic approach when assessing the impact of stress on a person. Hardiness is a combination of three characteristics: commitment, control, and openness to change. Together they provide the courage and motivation needed to turn stressful circumstances from potential calamities into opportunities for personal growth.2 Attitude can also influence the effect of stress on a person. People with positive attitudes view situations differently from those with negative attitudes. A person’s attitude also influences how he or she manages stress. To some extent, positive emotional attitudes can prevent disease and prolong life.3 Optimists are able to cope more effectively with stress. Optimism also reduces a person’s chances of developing stress-related illnesses. When optimistic people do become ill, they tend to recover more quickly. Pessimists are likely to deny the problem, distance themselves from the stressful event, focus on stressful feelings, or allow the stressor to interfere with achieving a goal. People with a more pessimistic attitude tend to report poorer health than people with optimistic attitudes.3 The following section discusses the roles of the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. These systems are interrelated, and that interrelationship is reflected in a person’s physiologic response to stress (Fig. 7-3). Further, stress activation of these systems affects other body systems, such as the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal, and reproductive systems. The complex process by which an event is perceived as a stressor and the body responds is not fully understood. A person’s response to a stressor (real or imagined, and physiologic or emotional/psychologic) determines the impact that stress will have on the body.4 Hans Selye, a pioneer in stress research more than 70 years ago, showed that stressors from different sources produced a similar physical response. He termed this physical response to stress the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), which has three stages: alarm reaction, stage of resistance, and stage of exhaustion.5 The GAS is presented in eTable 7-1 on the website for this chapter. The hypothalamus, which lies at the base of the brain just above the pituitary gland, has many functions that assist in adaptation to stress. Stress activates the limbic system, which in turn stimulates the hypothalamus. Because the hypothalamus secretes neuropeptides that regulate the release of hormones by the anterior pituitary, it is central to the connection between the nervous and endocrine systems in responding to stress (Fig. 7-4). The hypothalamus plays a primary role in the stress response by regulating the function of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system. When an individual perceives a stressor, the hypothalamus sends signals that initiate both the nervous and endocrine responses to the stressor. It does this primarily by sending signals via nerve fibers to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and by releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (see Chapter 48). Once the hypothalamus is activated in response to stress, the endocrine system becomes involved. The SNS stimulates the adrenal medulla to release epinephrine and norepinephrine (catecholamines). The effect of catecholamines and the SNS, including the response of the adrenal medulla, is referred to as the sympathoadrenal response. Epinephrine and norepinephrine prepare the body for the fight-or-flight response (Fig. 7-5). The stress response involves increases in (1) cardiac output (resulting from the increased heart rate and increased stroke volume), (2) blood glucose levels, (3) oxygen consumption, and (4) metabolic rate (see Fig. 7-5). In addition, dilation of skeletal muscle blood vessels increases blood supply to the large muscles and provides for quick movement. Increased cerebral blood flow increases mental alertness. The increased blood volume (from increased extracellular fluid and the shunting of blood away from the gastrointestinal system) helps maintain adequate circulation to vital organs in case of traumatic blood loss. Stress also has an impact on the immune system. Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) is an interdisciplinary science that studies the interactions among psychologic, neurologic, and immune responses.6 Because the brain is connected to the immune system by neuroanatomic and neuroendocrine pathways, stressors have the potential to lead to alterations in immune function (Fig. 7-6). Both acute and chronic stress can cause immunosuppression. Stress affects immune function by (1) decreasing the number and function of natural killer cells; (2) decreasing lymphocyte proliferation; (3) altering production of cytokines (soluble factors secreted by white blood cells and other cells), such as interferon and interleukins; and (4) decreasing phagocytosis by neutrophils and monocytes.7 (Natural killer cells, lymphocytes, and cytokines are discussed in Chapter 14.) Importantly, the network that links the brain and immune system is bidirectional (see Fig. 7-3). Signals from these systems travel back and forth, allowing for communication among these systems. Consequently, not only do emotions modify the immune response, but products of immune cells send signals back to the brain and alter its activity. Many of the communication signals sent from the immune system to the brain are mediated by cytokines, which are central to the coordination of the immune response. For example, IL-1 (a cytokine made by monocytes) acts on the temperature regulatory center of the hypothalamus and initiates the febrile response to infectious pathogens (see Fig. 12-3). The central nervous system is capable of influencing the function of the immune system. Stress-induced immunosuppression may exacerbate or increase the risk of progression of immune-based diseases such as multiple sclerosis, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer.7–9 Acute stress leads to physiologic changes that are important to a person’s adaptive survival. This is your “alarm system.” It puts you on high alert. However, if stress is excessive or prolonged, these same physiologic responses can be maladaptive and lead to harm and disease. Your body was not meant to be on high alert all of the time. When a person sustains chronic, unrelieved stress, the body’s defenses can no longer keep up with the demands. Therefore stress plays a role in the development or progression in the diseases of adaptation, or stress-related illnesses (Table 7-2). Stress is linked to leading causes of death, including cancer, accidents, and suicides. Stress can have effects on cognitive function, including poor concentration, memory problems, distressing dreams, sleep disturbances, and impaired decision making. Stress can also cause a wide variety of changes in behavior. These include people withdrawing from others, becoming quiet or unusually talkative, changing eating habits, drinking alcohol excessively, or becoming irritable.4,8–10 Long-term exposure to catecholamines resulting from excessive activation of the SNS may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and hypertension. Other conditions that are either precipitated or aggravated by stress include migraine headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and peptic ulcers.9,10 Control of metabolic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, is also affected by stress. Behavioral interventions aimed at stress reduction and relaxation have been successful in helping to manage these diseases in conjunction with standard medical therapy. Stressful life events can make a person more susceptible to infection. For example, psychologic stress may increase one’s risk for developing the common cold. In a landmark study, healthy volunteers were inoculated intranasally with low doses of upper respiratory tract viruses. The subjects underwent psychologic testing to determine the occurrence of stressful events in their lives and their reactions to such stresses. The results showed that the rates of both viral infection and clinical colds increased with the degree of psychologic stress. In this study, social support buffered the harmful effects of stress.11 Obesity and depression are often exacerbated by stress. Those who suffer from these conditions report that they are unable to take the necessary steps to relieve their stress or improve their health and therefore engage in maladaptive coping behaviors.12 At the cellular level, stress may promote earlier onset of age-related diseases. There is a link between stress and telomere length. Telomeres are the protective end caps on chromosomes, and their diminishing size is an indication of age. Telomeres are highly susceptible to stress and depression. Telomeres are shorter in people who are stressed and depressed than in healthy people. Thus chronic stress can have a long-term effect on our overall health by changing our DNA and accelerating the rate at which our cells age.13,14 Adverse experiences early in life have an impact on brain functions. Early life stress can program the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and eventually result in neurobehavioral changes.15 People exposed to major psychologic stressors in early life have elevated rates of morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases of aging. Children raised in poverty or mistreated by their parents have increased risk for vascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and premature death.16 Chronic stress is a major driver of chronic illness, which in turn is a major driver of escalating health care costs. It is critical that the entire health care community recognize the role of stress and unhealthy behaviors in causing and exacerbating chronic health conditions.12

Stress and Stress Management

Definition of Stress

Alarm

Resistance

Exhaustion

Low resistance to stressor

High resistance (adaptation) to stressor

Loss of resistance to stressor; may lead to death

Notes to Accompany Table

Selye’s early research using animals showed that stressors from different sources produced a similar physical response. He termed this physical response to stress the general adaptation syndrome, which has three stages: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

On encountering a stressor, the body undergoes an immediate alarm reaction. During this time, the fight-or-flight response is initiated. In this stage an individual’s resistance is decreased, which may result in disease or death if the stress is prolonged or severe. Ideally, an individual will move quickly from an alarm reaction to a stage of resistance.

During the stage of resistance, the individual is still exposed to the stressor, but physiologic reserves are mobilized to increase the resistance to stress. This is the time of adaptation. It is during this stage that the factors that influence stress, such as attitude or coping abilities, will positively or negatively affect the resistance to the stressor. No physical signs or symptoms can be seen while an individual expends energy to adapt to a stressor, but the body will become strained over time.

If all the energy is expended, the individual will move to a stage of exhaustion. At the stage of exhaustion, it is common to become ill and even die if assistance from an outside source is not available. This stage can often be reversed by external sources of adaptive energy, such as medication.

Factors Affecting Response to Stress

Physiologic Response to Stress

Nervous System

Cerebral Cortex.

Hypothalamus.

Endocrine System

Immune System

Effects of Stress on Health

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree