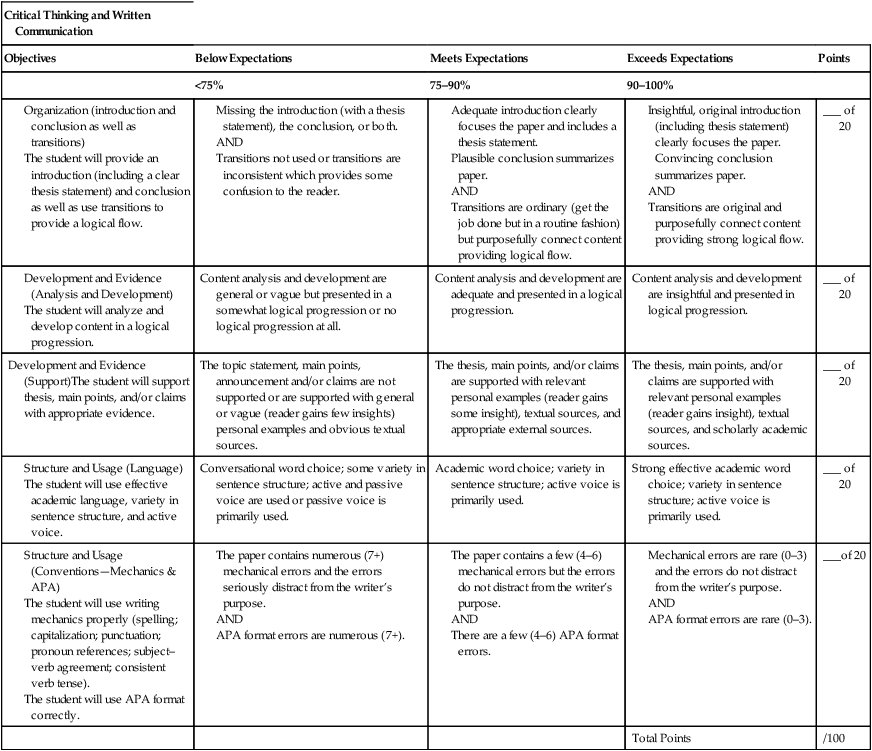

Jane M. Kirkpatrick, PhD, RN and Diann A. DeWitt, PhD, RN, CNE The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the uses, advantages, disadvantages, and issues related to a variety of strategies that faculty can use to assess and evaluate student learning. The Carnegie Foundation’s report on nursing education (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2009) calls for stronger integration of both clinical and classroom instruction and “radical transformation” in how nursing education is provided. Just as teaching methods are expanding to ensure that graduates achieve desired outcomes as identified by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) essentials (2008) and National League for Nursing (NLN) competencies (2010), we must also expand our assessment and evaluation strategies to determine if these competencies are attained. Competency in clinical judgment, critical thinking, and best nursing practices may need multiple measures to be evaluated accurately. As educators expand teaching methods and seek to assess deep learning and critical thinking, we can explore ways that our active learning teaching strategies can be transformed to assess the desired learning outcomes. The chapter includes practical information on a variety of outcome assessment strategies. Included are ways to select strategies, improve validity and reliability of the assessment strategies, and increase the effectiveness of their use. Just what is the difference between assessment and evaluation? In many instances it seems that these two terms are interchangeable. Assessment basically means obtaining information for a specific purpose. The information collected may be quantitative or qualitative depending on how it will be used (Brookhart, 2005). The main purpose of assessment is understanding and improving student learning (T. A. Angelo, personal communication, November 7, 2006). “It involves making our expectations explicit and public; setting appropriate criteria and high standards for learning quality; systematically gathering, analyzing, and interpreting evidence to determine how well performance matches those expectations and standards; and using the resulting information to document, explain, and improve performance” (Angelo, 1995, pp. 7–9). This definition of assessment is quite similar to formative evaluation, a process of determining progress with the goal of making improvements. 1. Clearly delineate the purpose of the assessment and evaluation. 2. Consider the setting in which the learning and assessment and evaluation will take place. 3. Choose the best assessment and evaluation strategy for the purpose. 4. Determine the procedure for the strategy selected. 5. Establish validity and reliability of the strategy. 6. Assess and evaluate the overall effectiveness of the process. The issues of validity and reliability are critical, especially when the purpose is for summative assessment and evaluation. The terms validity and reliability are defined and described in Chapter 24. For the purposes of this chapter, specific examples are given to clarify establishment of validity and reliability in nonmultiple-choice assessment methods. In determining validity, faculty must ask whether the assessment technique is appropriate to the purpose and whether it provides useful and meaningful data (Linn & Gronlund, 2005). Faculty must consider the fit of the assessment strategy with the identified objectives. In other words, does the strategy measure what it is supposed to measure? For instance, if the objective for an assignment is for the student to demonstrate skill in written communication, evaluating student performance through oral questioning will not provide valid data. Similarly, at the nursing department level, faculty should coordinate assessment and evaluation strategies with nursing program outcomes such as critical thinking and communication. It is a challenge to develop sound criteria for assessment that accurately reflect the specified outcomes, objectives, and content. To establish face validity, faculty must seek input from colleagues by asking questions such as “Do these criteria appear to measure what my objectives are?” In addition, obtaining the opinion of other content experts can assist in determining whether there is adequate sampling of the content (content validity). Whereas these types of validity (e.g., face, content) constitute the traditional approach to establishing validity, Gronlund (2006) asserts that this view is being replaced by validity as a unitary concept, based on several different categories of evidence (e.g., face-related evidence, content-related evidence). The evidence available to establish validity determines whether validity is considered low, medium, or high. Once assessment and evaluation criteria or rubrics are developed, it is essential to establish their reliability. The most commonly used method for establishing reliability in this situation is when two or more instructors independently rate student performance using the agreed upon criteria or rubric for sample work. Then the ratings are correlated to establish interrater reliability. Interrater reliability is expressed as a percentage of agreement between scores. An example of using criteria to establish interrater reliability is provided in Box 25-1. Educators must also be mindful of the domain of learning being assessed or evaluated (see Chapter 13). Cognitive learning is typically assessed with strategies requiring the students to write, submit portfolios, or complete tests (see Chapter 11). Assessment in the psychomotor domain typically involves simulations and simulated patients and ultimately occurs in clinical practice (see Chapters 19 and 20). Assessment in the affective domain is particularly important in nursing and is discussed further here. The taxonomy of affective assessment and evaluation as applied to nursing (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Mases, 1964) lists five behavioral categories: (1) receiving, (2) responding, (3) valuing, (4) organization of values, and (5) characterization by a value or value complex. The beginning student may be at the receiving level, able to hear and recognize the values. As the student progresses, more sophisticated affective growth would demonstrate the ability to respond to or communicate about the particular value or issue. At the next level, the student embraces the value. Ultimately, the student would act on the value. Once actions are consistent, the highest levels of the affective domain would be realized. When assessment strategies are used to collect data for grading purposes, it is imperative that the grading requirements be communicated to the students. Information about grading criteria is typically provided to students in the course syllabus. Other methods such as checklists, guidelines, or grading scales can be used as well. See Box 25-2 for an example of a writing assignment with grading rubric. Rubrics are another way to inform students about grading expectations. According to Stevens and Levi (2005), rubrics are rating scales used to assess performance. The two types of rubrics are holistic and analytic. The holistic approach is based on global scoring, often with descriptive information for each area based on a numerical scoring system, whereas analytic scoring involves examining each significant characteristic of the written work or portfolio. For example, in assessment of writing, the organization, ideas, and style may be judged individually according to analytic scoring (Linn & Gronlund, 2005). The global method seems more suitable for summative assessment, whereas the analytic method is useful in providing specific feedback to students for the purpose of performance improvement. Regardless of the type, rubrics are composed of four parts: (1) a task description (the assignment), (2) a scale, (3) the dimensions of the assignment, and (4) descriptions of each performance level (Stevens & Levi, 2005). The first portion of a rubric contains a clear description of the assignment and should be matched to the learning outcomes of the course. The next part of the rubric is a scale to describe levels of performance. Such a scale may include levels such as “excellent,” “competent,” and “needs work.” The dimensions of the assignment are the third part of rubric development, where the task is broken down into components. Last, differentiated descriptions of each performance level are explicitly identified. Rubrics thus provide clarity of expectations to assist students in the successful completion of assignments as well as making grading of these assignments more objective for the faculty. See Box 25-3 for an example of grading rubrics. Nursing faculty can use a variety of strategies to assess and evaluate student learning. This section identifies several strategies known to be effective in nursing. Table 25-1 provides an overview of these strategies. TABLE 25-1 Overview of Assessment and Evaluation Strategies

Strategies for assessing and evaluating learning outcomes

Assessment and evaluation

Selecting strategies

Validity and reliability

Matching the assessment strategy to the domain of learning

Communicating grading expectations

Strategies for assessing and evaluating learning outcomes

Technique

Domain and Assessment Purpose

Possible Applications

Advantages

Disadvantages

Issues

Portfolio (paper and electronic)

Role play

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Strategies for assessing and evaluating learning outcomes

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access