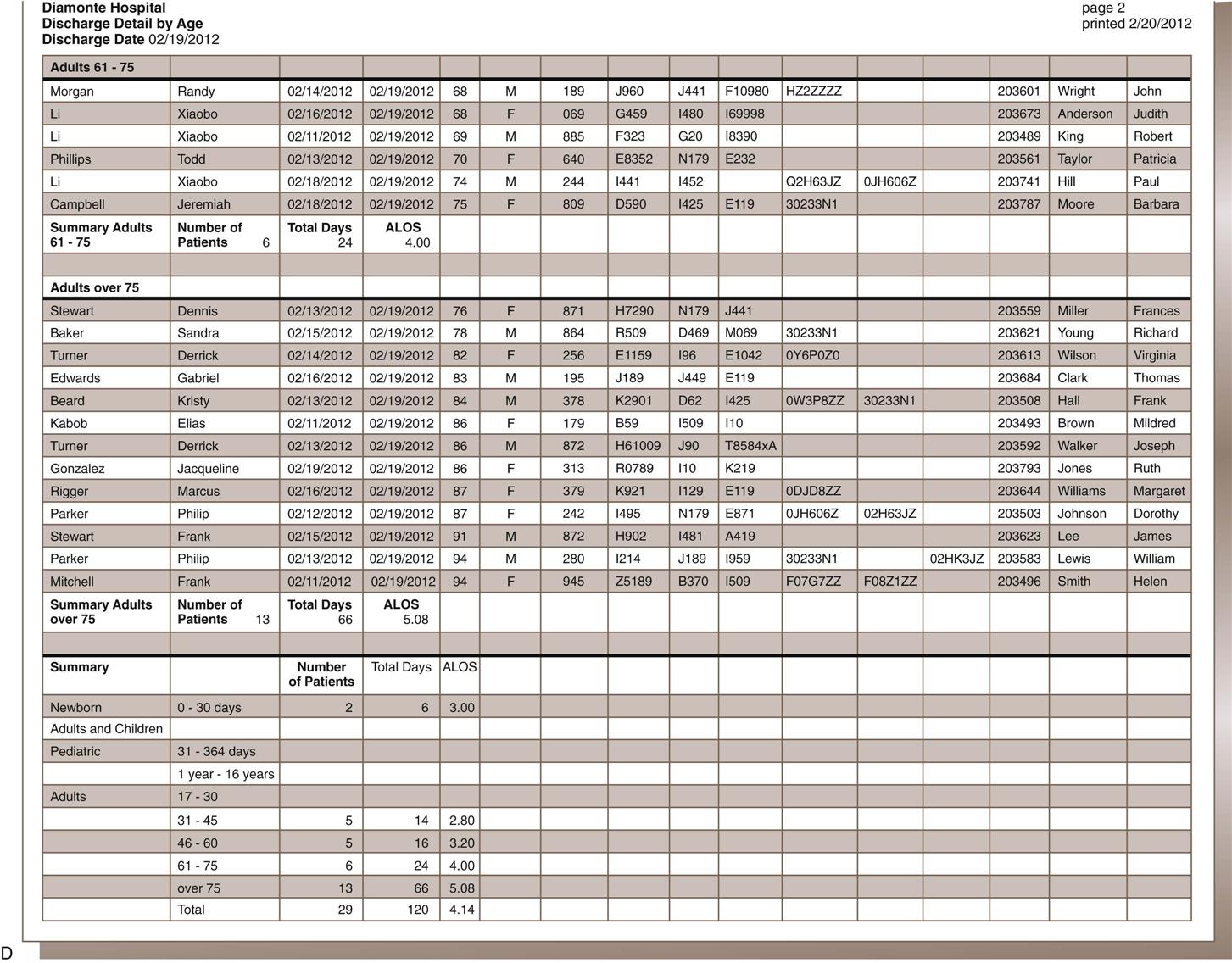

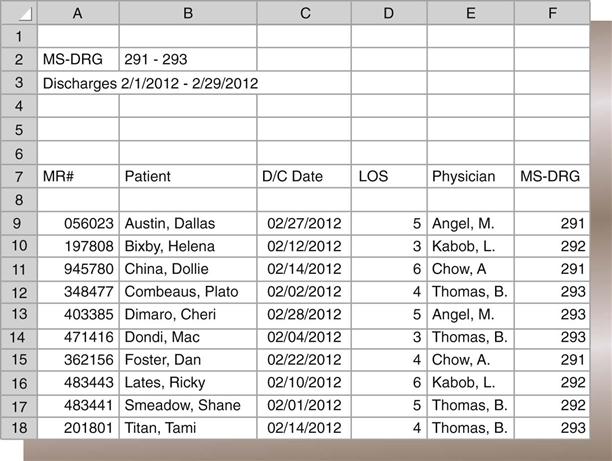

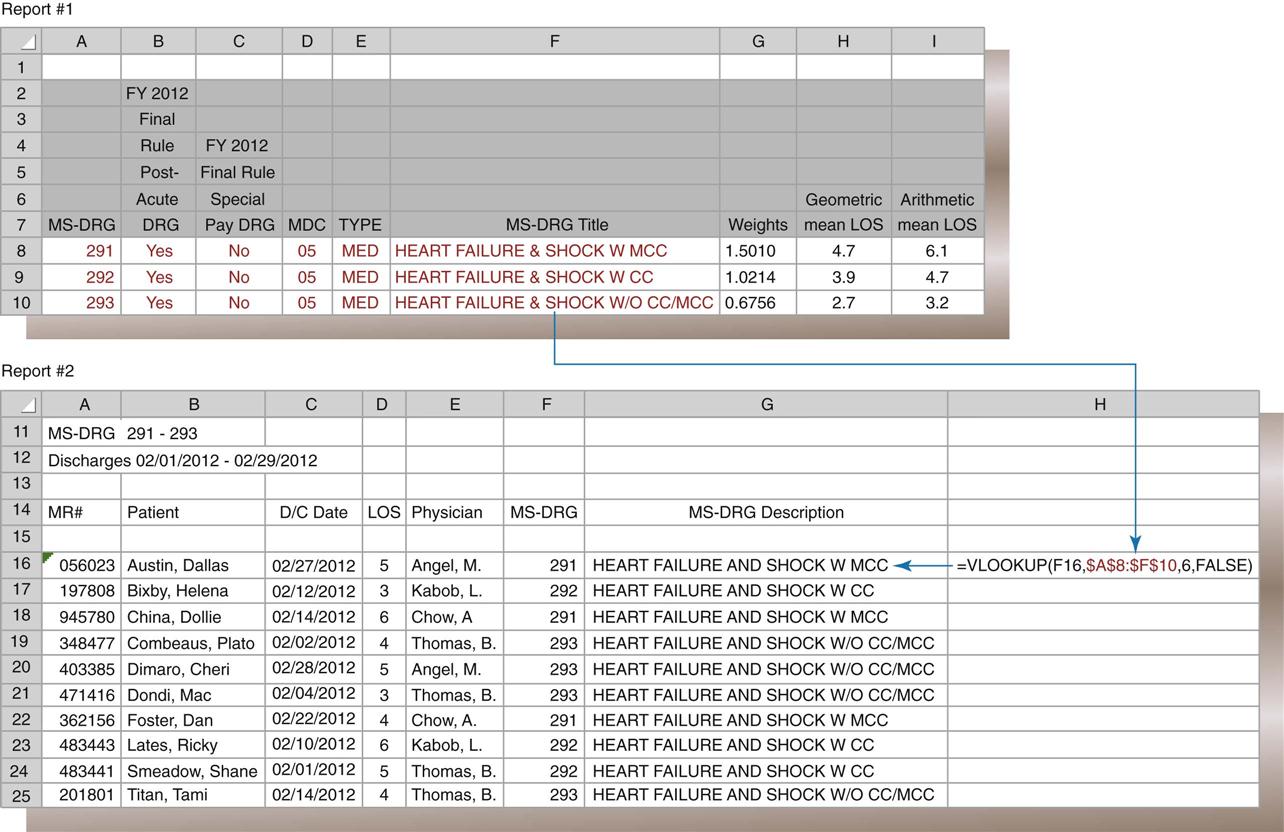

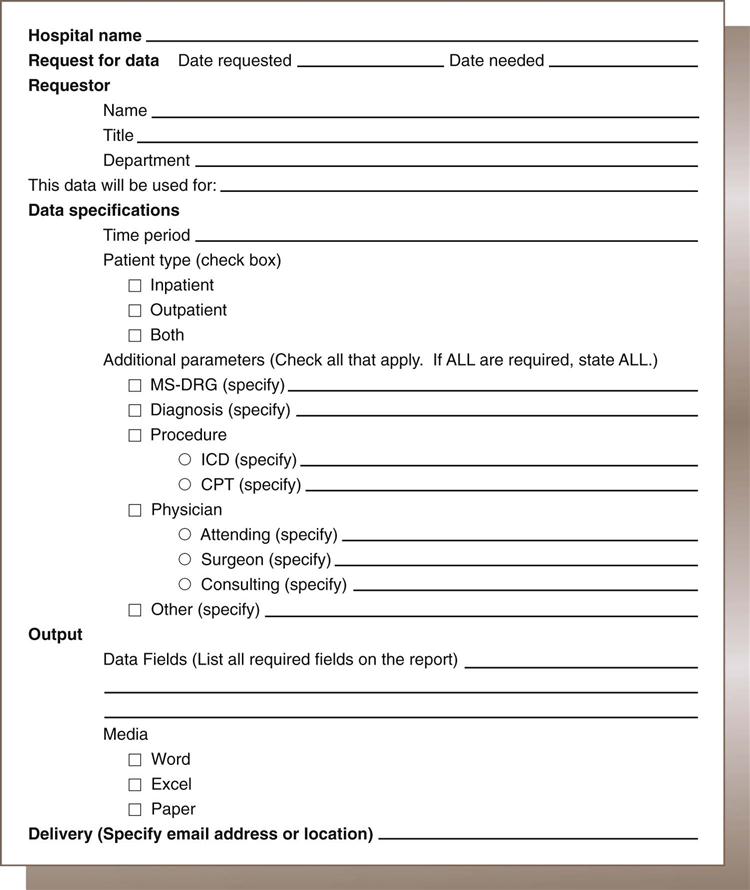

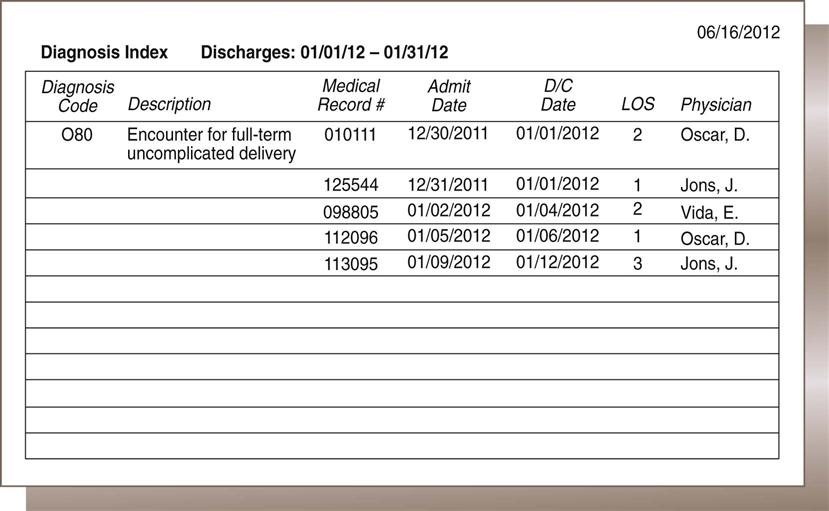

Nadinia Davis By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. Distinguish between primary and secondary data. 2. Explain the criteria for creating a report from a database. 3. List and describe four examples of indices that can be queried from a patient database. 4. Calculate the length of stay for a patient, given the admission and discharge dates. 5. Retrieve appropriate data according to the request. 6. Identify the optimal source for retrieval of information. 7. Describe and state the uses for statistical tools. 8. Compute routine institutional statistics. 9. Prepare graphic representation of data appropriate to the data type. aggregate data average length of stay (ALOS) bar graph bed control census central limit theorem class intervals discrete data frequency distribution histogram index inpatient service days (IPSDs) Institutional Review Board (IRB) length of stay (LOS) line graph mean median mode normal curve occupancy outlier percentage pie chart population primary data query random selection redact registry report sample secondary data skewed standard deviation statistics trend In earlier chapters, the collection of health data for documentation in the health record was discussed. The health record is used to gather health data for storage in a physical location or database to facilitate retrieval for future use. Organizing specific data elements for each patient allows reporting of health information as it is mandated by law, accreditation, or policy or as needed by authorized users. Important reasons to collect specific health data are statistical analysis, outcome analysis, and quality or performance improvement. Data analysis is a critical function in all health care facilities. To analyze data within one record or among multiple records, the health information management (HIM) professional must collect the data elements in the same way every time. An important function of the HIM department is the organized retrieval and reporting of these data. In previous chapters, the collection of health data was discussed in the context of providing proper patient care and following health care professional guidelines. The data were categorized into reports, such as the history and physical (H&P), laboratory reports, and nurses’ notes. This chapter focuses on the importance of collecting specific data in an organized format—such as a data set for input to a database—so that the health information can be analyzed and reported as necessary. Basic analytical and reporting strategies are explored. In order to be analyzed in a meaningful way, the data must first be collected appropriately. Appropriate collection of data is accomplished through the consistent use of forms and data screens to ensure timely, accurate, and valid data, as discussed in previous chapters. When one is using the data, it is important to understand the source of the data, including the most appropriate source for the purpose. Primary data come from original sources, such as patient medical records. These are the data that are collected or generated by clinicians while they are treating a patient. The clinician is the original recorder/reporter of the data: the firsthand account of the patient’s treatment. Examples of primary data are the history given by the patient to the nurse (Figure 10-1) and the patient’s blood pressure or temperature reading as recorded by the monitor or the nurse. These data elements are documented in the patient’s health record in a format that helps transform the raw data into usable information. Because the data are from the original patient record, they are considered primary data. Primary data are used when the identity of the patient is relevant to the user or the events recorded in the record are the focus of the review. For example, a physician who wants data for continuing patient care would be interested only in the patient-identifiable data from that specific patient’s chart. A performance improvement team reviewer looking for compliance with protocols would probably need to review primary data. Secondary data come from sources other than the original recorder/reporter of the data. Scholarly articles and aggregate (summarized) data are secondary sources. Census data and publicly available mortality data are examples of secondary health data. Abstracted data (data selected and reported from the health record) are secondary data and can be sorted and made available in a variety of formats. For example, a list of discharges sorted by physician is a physician index. The physician index is secondary data. Secondary data may be patient identifiable or may be redacted (patient identity removed) (Figure 10-2). Hospital administrators and managers use both primary and secondary data for monitoring, tracking, and forecasting hospital and departmental activities, for example. Physicians may use such data for tracking volume and outcomes. Questions such as “How many?” “How often?” and “How well?” may be answered through analysis of the appropriate data. For example, a physician might want a list of patients that she treated for a specific diagnosis or with a specified procedure, or to answer the question: Which of my patients had a principal diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or On which of my patients did I perform surgery? In these cases, the identity of the patients is relevant to the physician, and primary data would be accessed in order to provide the data. The report itself, however, is secondary data. The report might contain only a list of the patients and perhaps the relevant identification numbers. The report gives no insight into other issues that might be relevant to the cases. A hospital administrator may want to know how many cases of a particular surgical type were performed during a period of time. Although the primary data would be used to produce the abstracted report, the patient-identifying information would not be relevant—it would be omitted from the report. If the report generated from the computer system contains patient identifiable data, such as name, such data would be redacted (removed or blocked) from the report before the report was transmitted to the administrator. Such secondary reporting and analysis of patient data is the focus of this chapter. Because each data element is defined before it is collected, the database is a useful source of information. For example, “attending physician” is one of the data elements collected. One can collect this data element in the admission record by entering the identification number for the physician who matches the description of the attending physician (see Table 4-1). This information is reported on the Uniform Bill (UB-04) for each patient discharged. The collection of this data element on all patients in the database makes it possible to query, or ask, the database for information specific to the attending physician. For example, facilities should review a representative sample of records on all physicians on the medical staff at the facility when conducting studies of documentation and quality. To do so, the user must be able to run a report that lists records for each physician. The ability to query the database on the attending physician data element is therefore quite useful. In addition to documentation and quality studies, such a report might also be part of a review of physician practice patterns, including patient volume. As noted previously, some data are required by the federal government and other payers. However, other data elements are collected only as specified by the facility. These types of data must be collected in the way in which they will be useful in the future. For example, in some cases, the type and frequency of consulting services, such as cardiology, and infectious disease, may influence the patient’s outcomes and length of stay. To collect this type of data (if not already captured), as each patient record is abstracted, the HIM professional identifies consulting services and enters the corresponding physician identifiers into the abstract. Later, the user can access that information in the database in the way that he or she prefers. For example, the user might look at consulting services associated with a specific diagnosis or procedure or with a particular attending physician. Examples of additional data that might be captured are type of anesthesia, length of surgery, and consent details. An example of other data that may be collected is advance directive acknowledgments. Facilities can include fields containing Yes or No to capture whether a patient has signed the advance directive acknowledgement statement or whether the patient has signed an Advance Beneficiary Notice (ABN), accepting responsibility for charges not payable by Medicare. Copies of the documents themselves would be on file, but their presence is not retrievable as a data field unless specifically captured. This Yes/No field is an example of a discrete data point: a named and identifiable piece of data that can be queried and reported in a meaningful way. ICD-10-CM/ICD-10-PCS codes and medical record number are also examples of discrete data. Certain services provided to patients and supplies used to treat patients are not separately payable. However, hospital administration may wish to track such services and items for staff productivity or inventory control purposes. One way to do this is to enter charges to the patient’s account that have no dollar amount associated with them. These data, then, would also be available for abstraction and analysis by authorized users. When all required elements of the patient’s data have been captured, the abstract is considered complete. All patient records must be abstracted as required to satisfy payer and facility guidelines for specific data. Each patient receiving services in a health care setting has an abstract. However, the abstract differs according to the setting (e.g., ambulatory care, long-term care). By collecting this data in the abstract, the facility is able to query the system (run reports) for information related to these topics. Some of the typical queries of the abstract database are as follows: For maintenance of a functional database, abstracted data must be audited for quality: validity, accuracy, completeness, and timeliness, for example. To do so, an HIM professional other than the initial clerk, usually a supervisor, routinely audits the abstracts by pulling the patient health record, retrieving the abstract from the database, and verifying the data elements. In general, only a sample of the abstracts is reviewed. However, the supervisor must be sure to choose a random sample of abstracts that includes all of the employees’ work. Errors are corrected, documented, analyzed, and tracked to improve the quality of the database. The quality of the data is extremely important because of the high volume of information that the database provides for the health care facility. The quality of the database enables performance improvement activities and appropriate decisions about the facility or about individual patients. Remember that data quality audits must be recorded for future comparison. It is important to document compliance or noncompliance with a set standard of quality for data. Over time, this information provides support for improvement efforts, indicates a need for improvement, or demonstrates quality. Discussion of database quality in the context of an electronic health record is continued in Chapter 11. Once a database exists, the data can be used for analysis or comparison. When health information is needed for utilization review, quality assurance, performance improvement, routine compilation, or patient care, the HIM department is asked to retrieve relevant data. With the right instructions on the type of information needed and its intended use, HIM personnel can provide high-quality health information on both individual patients and groups of patients. Compilation of health data for groups of patients is called aggregate data. Aggregate data are a group of like data elements compiled to provide information about a group. For example, a collection of the length of stay (LOS) for all patients with the diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) would be aggregate data, as shown in the report in Figure 10-4. Further review of the report shows that the LOS data element for each patient has been retrieved. This report can be analyzed to determine the average LOS and the most common LOS. Sorting by any single data element for each of these patients produces a meaningful list of aggregate data. Requests for data come into the HIM department frequently. Most of these requests are routine and can be satisfied quickly. Others are more complex and may require some analysis. In either case, the HIM professional needs to record the request in detail, partly to evaluate whether the request can be granted and partly to clarify the exact requirements of the requester. The following details are helpful: the name and contact phone number of the person making the request, the date of the request as well as the date parameters for the information requested, the specific information requested, and the reason for the request. This information helps the person querying the database ensure that the most appropriate information is retrieved from the database and provides an audit trail for accounting of disclosures. The facility should have an administrative policy regarding who may obtain data and for what purposes. For example, residents may need to collect data on their own patients for educational purposes; however, a study involving other patients would require either faculty or possibly Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Similarly, Dr. Braun may request data on her own patients, but not on the patients of Dr. Wong. Data requests should be formatted in order to ensure clarity and reduce the potential for error. Figure 10-5 illustrates a sample data request form. Note that the parameters for the report include the time period, the specific data elements requested, and the desired format of the output. In many cases, output format is determined by the system when predesigned reports are used. If it is possible to remove unnecessary data elements prior to delivering the report to the requestor, such removal should be done. For example, if patient identity is not required, then patient name and account references should be removed from the report. Most systems provide for custom report design, which may or may not be the responsibility of the HIM department. The ability to identify and extract data from a database is a useful skill that renders the user a more valuable member of the organization. Combined with an HIM professional’s knowledge of the underlying data, particularly code sets, this is a desirable skill in his or her practice. The first step to retrieving appropriate useful information is to identify the population of interest. In health care a population can be defined as a group of people identified by a particular characteristic or group of characteristics, such as race, age, gender, diagnosis, procedure, service, or financial class. From hospital data, one can also identify patients by date of admission, date of discharge, charge code, payer, or virtually any data element that is resident in the database. The population, then, consists of all patients with the characteristic under consideration. For example: all inpatients discharged between January 1, 2012, and June 30, 2012, with a discharge status of 20 (expired). The next step is to narrow the data request, if desired. Although some users may want to review all of the patients in the population, rarely will the user need all of the available data. Therefore the output of the data retrieval must be specified. In many systems, there are preformatted (a.k.a. “canned”) reports that contain standard output that users would typically need: diagnoses, procedures, admission and discharge dates, gender, age, financial class, medical record number, patient account number, and patient name. Customized reports may also be available. For a customized report, it is important to be very specific as to the output desired. The user will get only what the user has specified. Therefore, if the attending physician’s name is required, the user must ask for the attending physician’s name to be included in the report. A common reason to request data is for surgical case review or utilization review. For these studies, the population of patients may be based on a diagnosis or the operation that was performed and includes the period under study. Sometimes, the population is too large to be analyzed. This is often the case with coding audits. It is usually too expensive for auditors to review a population of 100% of the charts in a month, for example. Therefore a sample is generally chosen from the population. A sample is a small representation of the entire population. The next matter to discuss with regard to data retrieval is how to ascertain the optimal source of the data. In a well-constructed database, with unique data dictionary definitions, the computer program will have stored the data in only one place. Therefore the data will always be recorded at the best time by the best person, as defined in the data dictionary. For instance, the data dictionary probably specifies that the data element for a patient’s name—and most other demographic data—will be recorded by the patient registration department when the patient arrives at the facility. Once the patient’s name is recorded at registration, it is available in the system to populate electronic forms for all users. The name is not entered again and again by each user. Similarly, a nurse enters nursing assessments and notes—they are not entered by HIM personnel. The final diagnosis and procedure codes are stored in the system upon abstraction, and not a second time. For retrieval of a population report of all of the patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia, there is only one database where the patient’s diagnosis is recorded: in the abstract. Thus writing a query or searching the database requires the user to understand the location of the data. However, in a paper record, understanding the optimal source of data becomes critical. In many paper environments, the same information is recorded multiple times. The patient’s admitting diagnosis, for example, is recorded on the face sheet by the admitting clerk; it is recorded on the nursing assessment by the nurse; and it is recorded on the admitting notes by the physician. What is the optimal, most reliable place to determine the patient’s admitting diagnosis? It depends on the reason for the review. If one wants to learn why the patient thought he or she was admitted, the face sheet is probably the most important place to look. However, if one wants to know the physician’s clinical reason for admitting the patient, the admitting note or the history and physical are better places to look. Another example of how important it is to identify the optimal source of data is during a survey by The Joint Commission (TJC). TJC surveyors may ask to review specific records (e.g., records of patients who were restrained). This information is not normally identified in the patient abstract. From the HIM perspective, several different data elements in the database can indicate that a patient may have been restrained. In an electronic system, a special data field can be added to indicate (Yes or No) whether a patient was restrained. If a special data field does not exist, other information in the abstract may help identify patients who were restrained. For example, a certain diagnosis indicates that a patient may have required restraints (e.g., organic brain syndrome or delirium). Optimally, there are appropriate and timely orders, nursing notes describing the application, duration, and monitoring of the restraints, and a restraints log maintained on the nursing unit; still, the surveyors may want to obtain corroborating evidence or to search for missing documentation. Trying to find the optimal source of data requires knowing the database and knowing how to query it and relate the data elements, as well as a bit of detective work. Sometimes one has to begin with known data and work backwards. For instance, if the chief financial officer wants to know how many fertility treatments were performed in the facility, the user would have to know the procedure codes for fertility treatments in order to query the system for all of those procedures. The result should be a list of patients, their health record numbers, and the fertility procedures performed. Another requestor may want a list of cases for MS-DRG 312 (Syncope and Collapse) and the total charges for each case. The HIM professional might have two canned reports: one that contains the DRG, but not the total charges; and another that contains the total charges, but not the DRG. If the requestor wants both, the professional has to look for a common field—usually the patient account number—and combine the two reports to get what the requestor wants. One common task of this nature is the insertion of an MS-DRG description into a report that contains only the MS-DRG itself. Figure 10-6 illustrates the latter example in which the VLOOKUP function in Excel is used. An index is a list that identifies specific data items within a frame of reference. The abstracting process has enabled facilities to create indices for diagnoses, procedures, and physicians. For example, the attending physician is systematically identified on each patient record during the abstract process. A listing of patients by attending physician creates what is called the physician index. Additional indices can be created if the data are captured in the system. Referring physician, primary care physician, and consulting physician are typically captured, and each surgical procedure has a performing physician’s name attached to it. Therefore reporting lists of visits by physician relationship is possible. The database can also provide information about any group of patients according to the instructions given by the person requesting the information to HIM personnel and further refined by HIM personnel queries to the database. As with any other data, the quality of the data capture dictates the completeness and accuracy of such reporting. It should be noted that physician attribution (the assignment to a case of a physician and the physician’s relationship to the case) is a matter of some importance to the physicians themselves. Increasingly, payers are reviewing facility and physician claims together and assessing whether the billing is consistent. As such, if a physician submits a claim as an attending physician, but the facility has a different physician listed as attending, then the payer may question either or both claims. Physician attribution is also an important issue for recredentialing. A physician may have a minimum volume requirement in order to maintain privileges at a particular facility. Indices may also be generated on the basis of the principal diagnosis or the principal procedure. Although indices were a very important tool in the retrospective analysis of patient data before computerization, the automation of data collection and on-demand printing make the necessity for routinely maintaining physical copies obsolete. However, in the event of a system conversion (abandoning an old system for a new one), care should be taken to preserve the historical data. Hospitals may be required by state regulation to retain the master patient index permanently, and abstracted data may logically be attached during the conversion. Figure 10-7 shows a diagnosis index of diagnosis code O80 for discharges in January 2012 in computerized format. Health data are used by various departments in the health care facility. The performance improvement department uses the database to retrieve specific cases and review the documentation found in the health records to determine compliance with accreditation standards, perform performance improvement studies, or study patient care outcomes. The finance department may use charge data to verify or prepare financial reports and budgets. Case management may perform retrospective reviews to investigate admission denials. Infection control needs to identify and analyze reportable infectious disease cases. The HIM department has many customers for data, both internal and external. Various agencies associated with health care facilities routinely require information. Some states gather information from facilities to create a state health information network. The information in the database is shared (without patient identifiers) so that facilities can compare themselves with other facilities. Organ procurement agencies may request information on deaths for a certain period to assess the facility’s compliance with state regulations for organ procurement. Certain statistics must be reported to the CDC so that disease prevalence, incidence, morbidity (illness), and mortality (death) can be studied. Prevalence is the portion of the population that has a particular disease or condition. Incidence is how many new cases of a particular disease or condition have been identified in a particular period in comparison with the population as a whole.

Statistics

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Organized Collection of Data

Primary and Secondary Data

Creation of a Database

Data Review and Abstracting

Data Quality Check

Data Retrieval

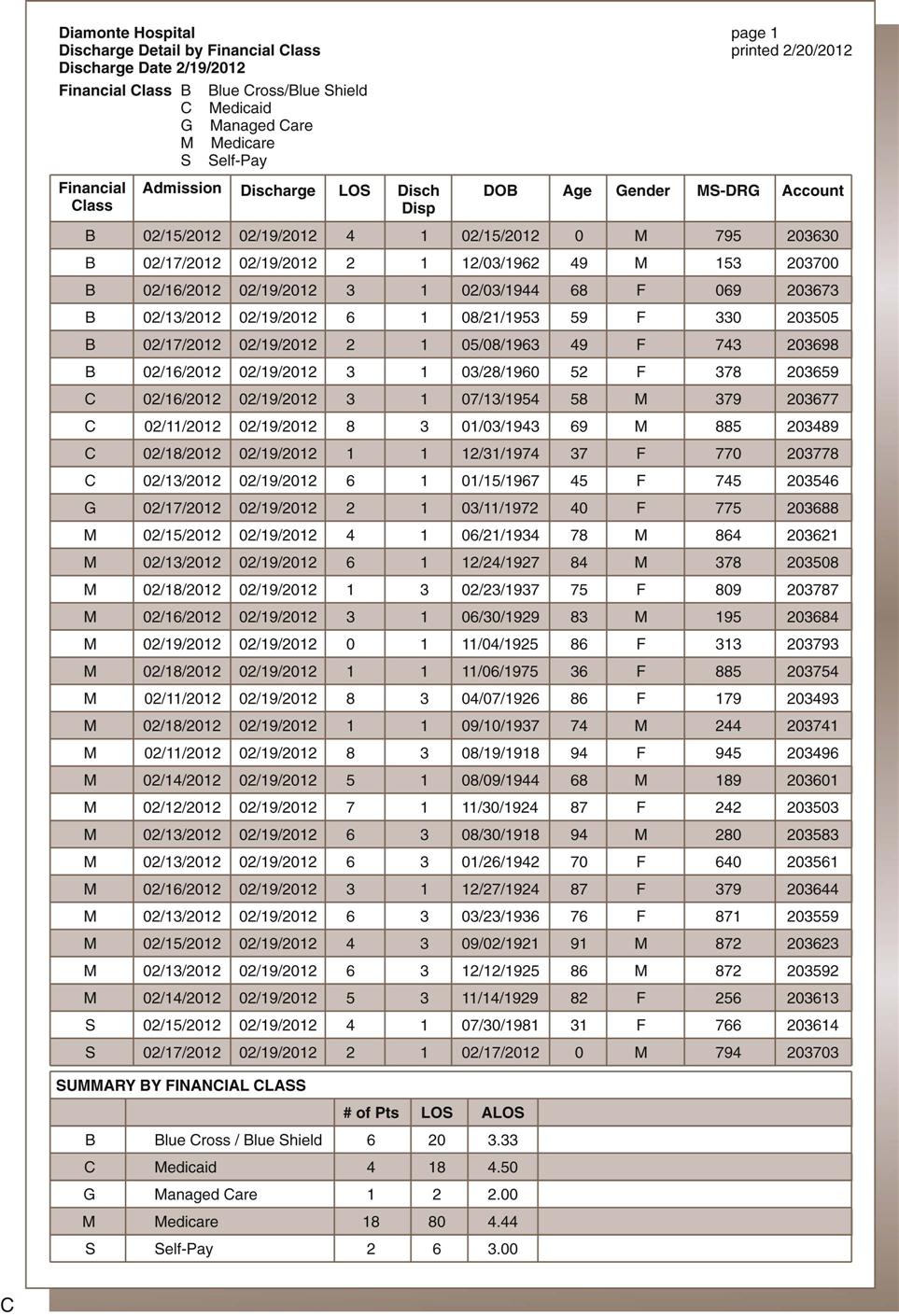

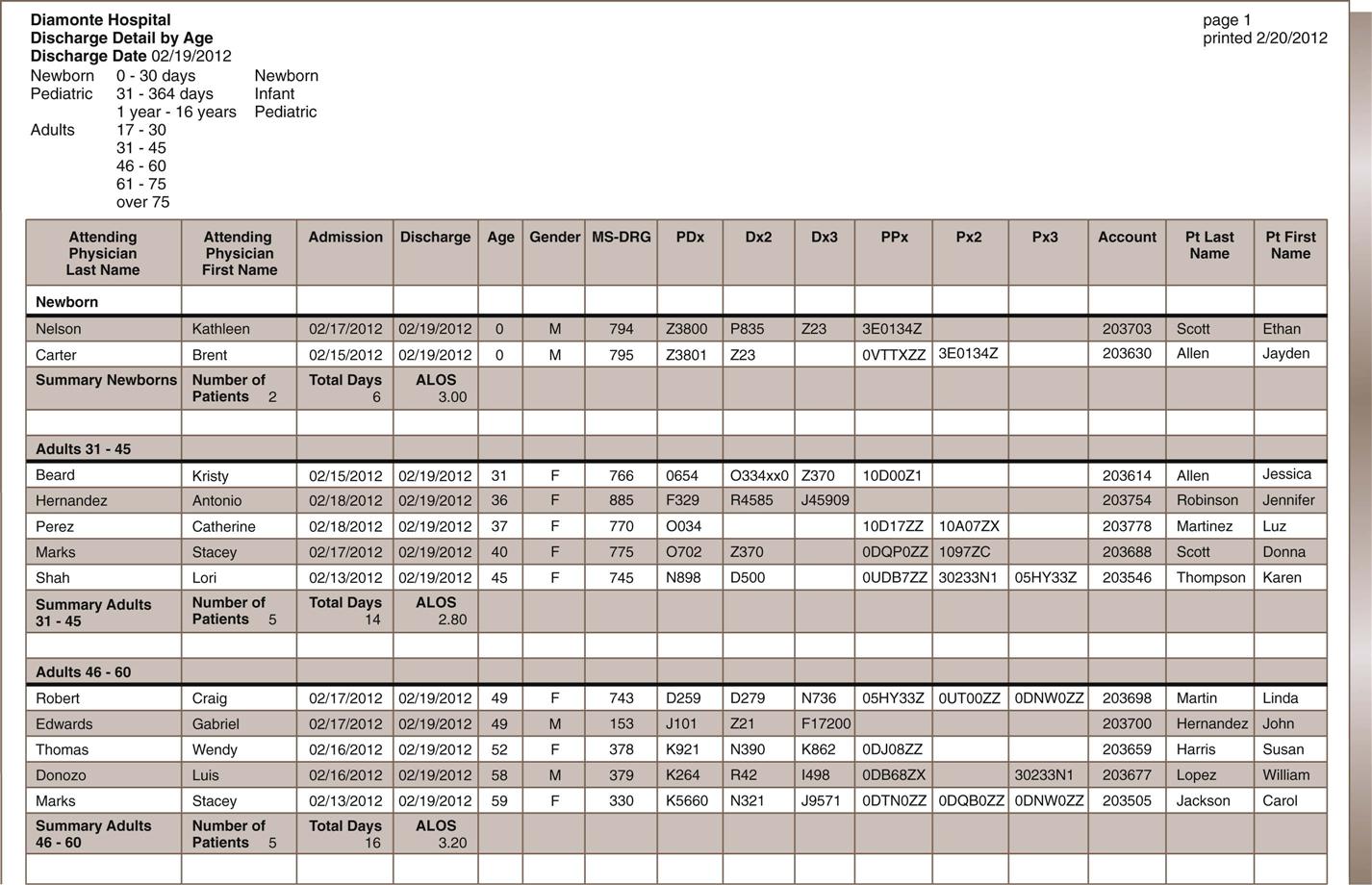

Retrieval of Aggregate Data

Retrieving Data

Optimal Source of Data

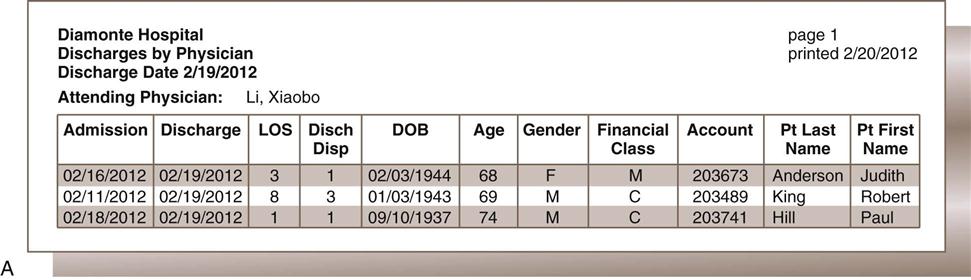

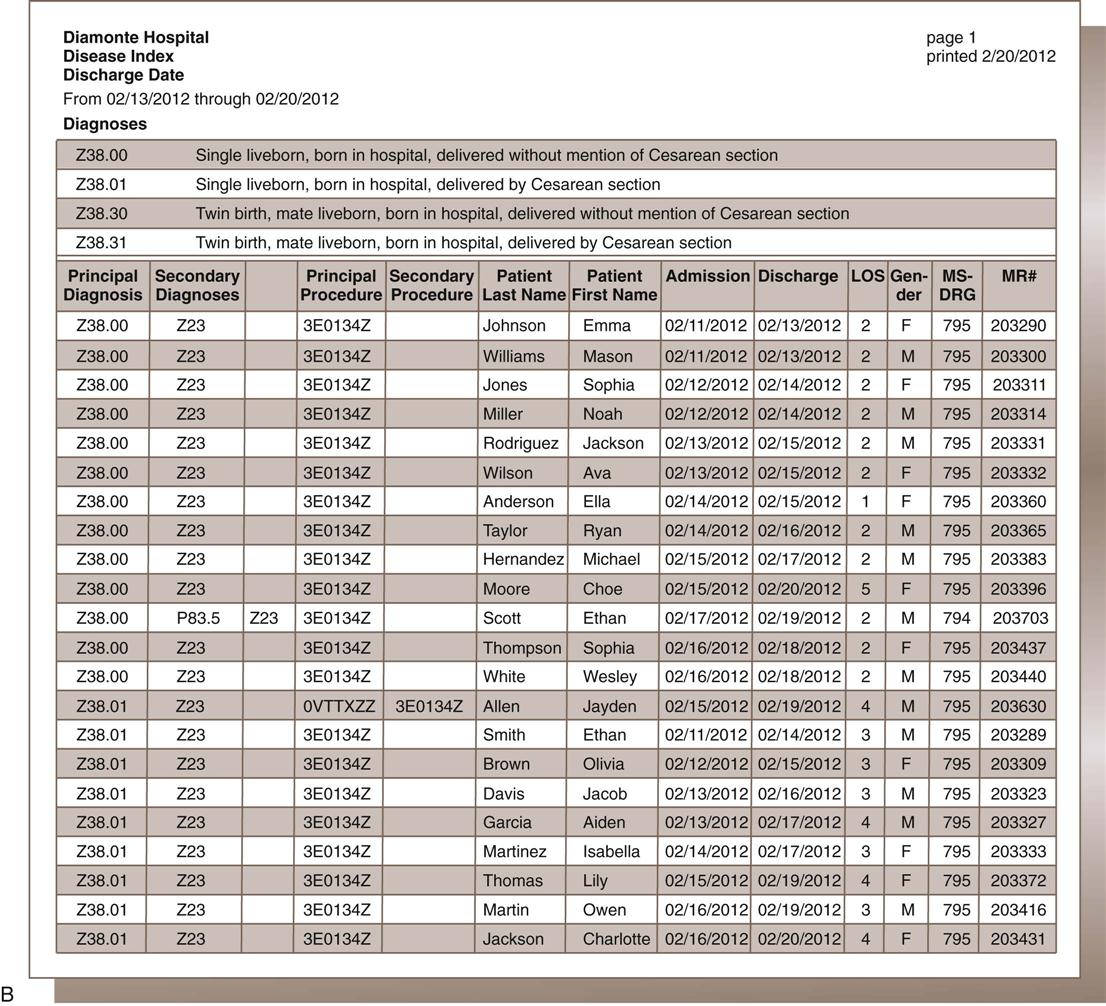

Indices

Reporting of Data

Reporting to Individual Departments

Reporting to Outside Agencies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Statistics

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access