Chapter 21

Staffing and Scheduling

Sharon Eck Birmingham, Beth Pickard and Lori Carson

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

Nurse staffing methodology eloquently articulated by Aydelotte in the early 1970s continues as a critical issue affecting the quality, safety, and cost of U.S. health care today (Aiken et al., 2002; Aiken et al., 2003; Blegen & Goode, 1998; Hinshaw, 2006; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2004; Kane et al., 2007a, b; Kovner & Gergen, 1998; Litvak et al., 2005; Needleman et al., 2002; Needleman et al., 2006; Needleman et al., 2011; Unruh, 2008). Nursing is essential in the delivery of health care to society. Nursing’s Social Policy Statement reflects the societal contract for the provision of safe and quality nursing care and services for all people in every health care setting (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2010a). The major goal of staffing management is to provide the right number of nursing staff with the right qualifications to deliver safe, high-quality and cost-effective nursing care to a group of patients and their families as evidenced by positive clinical outcomes, satisfaction with care, and progression across the care continuum (Eck Birmingham, 2010; Warner, 2006).

Staffing management is one of the most critical yet highly complex and time-consuming activities for nurse leaders at every level of the health care organization today (Abdoo, 2000; Sullivan et al., 2003). How well or poorly nursing leaders execute staff management impacts the safety and quality of patient care, financial results, and organizational outcomes, such as job satisfaction and retention of registered nurses (RNs) (Beyers, 2000). The purpose of this chapter is to assist students and nursing leaders at all levels to understand the complex issues associated with staffing management in patient care. A framework for staffing management is presented, and critical components of the staffing management plan are described. New evidence that fosters an understanding of the effects of RN fatigue, independent of staffing, on quality is presented. Technology tools for frontline nursing leaders to foster the alignment of roles and accountability for staffing management are discussed. Additionally, the IOM (2010) report on the future of nursing articulates many recommendations to strengthen the advancement of evidenced-based staffing and they are explored here.

DEFINITIONS

Staffing terminology in nursing is multifaceted and often confusing, with a specific set of terms used. The most common staffing terms are defined in Box 21-1. Staffing strategies reflect the hospital’s mission, and annual strategic goals and are executed to meet the staffing management plan of an organization. Chief nursing officers are accountable to establish and translate staffing management strategies for the overall patient care divisions. The nurse managers accountable for a patient care unit or area execute the staffing management strategies, to yield an optimal health experience and clinical outcomes for patients and their families; a healthy, satisfying work environment; and cost-effective staffing model for the organization. Nursing leaders at all levels are challenged to clearly identify the leadership roles that are accountable for staffing management and adopt technologies that provide the real-time tools to execute, measure, and achieve the desired outcomes.

FRAMEWORK FOR STAFFING MANAGEMENT

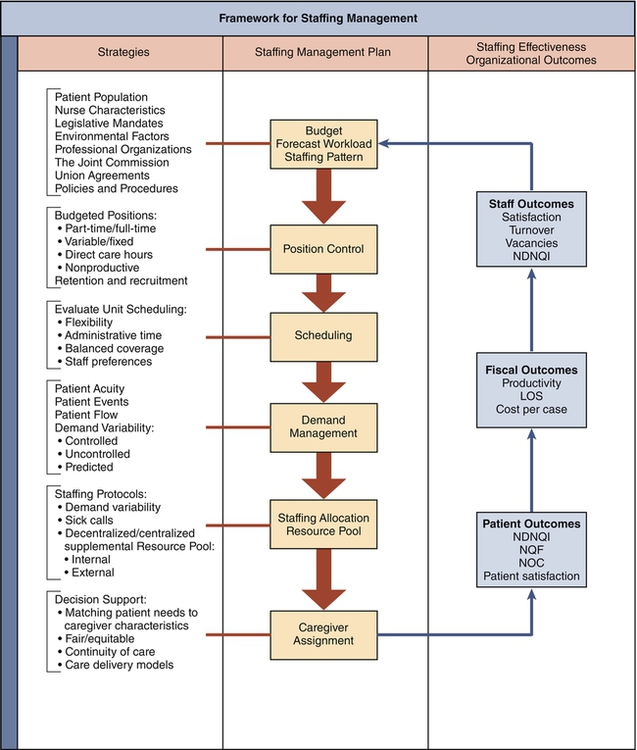

Staffing management is complex and challenging because of the numerous dependencies and interrelated organizational processes. A conceptual framework provides logic and order to complex processes for administrators and scientists to consider (Edwardson, 2007). A conceptual framework for staffing management is proposed and illustrated in Figure 21-1.

This conceptual framework is adapted from Donabedian’s (1966) framework for the evaluation of quality of care: relating various structures (e.g., hospital characteristics) that impact various processes (e.g., actual staffing) and subsequently influence various outcomes (e.g., patient quality, patient satisfaction, and staff satisfaction). Multiple staffing studies have adapted this framework to organize the variables of interest (Cho, 2001; Eck, 1999; Edwardson, 2007; Kane et al., 2007a, b; Mark et al., 2007; Mark et al., 2004). In the proposed framework, structures represent the various nursing strategies, both internal and external to the organization, which directly influence an organization’s ability to effectively manage processes for staffing. The processes are a series of defined stages with outputs that directly affect subsequent stages of staffing. Finally, the outcomes of staffing management are multidimensional and measured in terms of organizational outcomes including patient, fiscal, and staff outcomes. The staffing management framework is not intended to address all possible variables but, instead, is intended to provide a guide for nursing leaders to assess staffing management in their organizations.

STRATEGIES INFLUENCING STAFFING MANAGEMENT

American Nurses Association Principles for Nurse Staffing

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has published guiding documents that serve as resources to understand the complex staffing issues associated with creating a nursing unit schedule, an organization-wide staffing plan, or meeting staffing legislation. Principles for Nurse Staffing (ANA, 1999) was developed by an appointed expert panel to guide nurse staffing. The nine principles are organized into three categories pertaining to the patient care unit, the staff, and the organization (ANA, 1999). The nine principles capture the complexity of nurse staffing and offer an excellent guide for dialogue among nursing leaders. Principles related to the patient care unit are the following (ANA, 1999, p. 2):

A Appropriate staffing levels for a patient care unit reflect analysis of individual and aggregate patient needs.

B There is a critical need to either retire or seriously question the usefulness of the concept of nursing hours per patient day (HPPD).

C Unit functions necessary to support delivery of quality patient care must also be considered in determining staffing levels.

Principles related to nursing staff are the following (ANA, 1999, p. 2):

A The specific needs of various patient populations should determine the appropriate clinical competencies required of the nurse practicing in that area.

B Registered nurses must have nursing management support and representation at both the operational level and the executive level.

C Clinical support from experienced RNs should be readily available to those RNs with less proficiency.

Principles related to the organization are the following (ANA, 1999, p. 2):

A Organizational policy should reflect an organizational climate that values registered nurses and other employees as strategic assets and exhibit a true commitment to filling budgeted positions in a timely manner.

B All institutions should have documented competencies for nursing staff, including agency or supplemental and traveling RNs, for those activities that they have been authorized to perform.

C Organizational policies should recognize the myriad needs of both patients and nursing staff.

As the nursing shortage intensified, the ANA (2005) responded with an updated Utilization Guide for the ANA Principles for Nurse Staffing. This report highlighted several policy perspectives: (1) the value of direct-care nurses’ input into an organization’s staffing plan; (2) the value of direct-care nurses’ input into the selection and implementation of patient classification or acuity systems; and (3) the value of both the clinically skilled and experienced RN who is familiar with the specific patients and nursing staff rendering their professional judgment regarding staffing decisions. This guide is an excellent document relevant for all nursing leaders and staffing committees for dialogue and planning.

Patient Acuity

Technology advancements foster adoption of the ANA staffing principles for annual budgeting and in everyday practice. Unfortunately, most patient classification systems aimed at adjusting staffing for acuity have been plagued with an inability to accurately and reliably measure patient care variability. Further, they have lacked organizational credibility and added burden to the direct care nurse. In recent years, health care reform and meaningful use legislation (HITECH act) has catapulted the advancement of health information technology to widespread adoption of electronic medical records (EMR) in the United States (www.hipaasurvivalguide.com/hitech-act-summary.php). These advances additionally offer nursing leaders technologies that leverage the automated patient assessment information entered into the patient EMR by nurses to generate accurate measurements of patient acuity (Eck Birmingham et al., 2011). The electronic patient assessment information is translated into not only workload information at the patient level, but also standardized outcomes of care (Moorhead et al., 2008) that may assist the nurse and care team in tracking patient progression to the anticipated Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) and length of stay (Eck Birmingham, 2010). The objective patient acuity information generated as a by-product of routine clinical documentation allows frontline charge nurses to make informed patient care assignment decisions. From the chief nurse’s perspective, new acuity technologies help build the business case for acuity-adjusted staffing for both improved quality and cost outcomes (Dent & Bradshaw, 2012).

Nursing Care Delivery Models

Nursing care delivery models significantly influence staffing management. A nursing care delivery model “is defined as a method of organizing and delivering nursing care in order to achieve desired patient outcomes” (Deutschendorf, 2010, p. 444). Examples of nursing care delivery models include patient-focused care, team nursing, private duty nursing, total patient care, functional nursing, primary nursing, and various combinations.

Manthey (1990) and Person (2004) described the four fundamental elements of any nursing care delivery model as follows: (1) nurse/patient relationship and decision making; (2) work allocation and patient assignments; (3) communication among members of the health team; and (4) management of the unit or environment of care. Translating the nursing care delivery model’s elements and inherent values to staffing management is a key role for nursing leaders (ANA, 2004). One common element among care models is the value of the nurse and patient/family relationship. Patient assignment technology offers charge nurses access to real-time data in order to match the right nurse (i.e., competency, expertise) with the right patient and provide continuity of care during an episode of care. A second common trend is the evolving role of the charge nurse as the frontline leader with responsibility to coordinate patient flow with expert communication among health care team members. Increasingly a charge nurse is appointed as a resource, managing patient flow and supporting novice nurses, and thus does not assume a direct care assignment.

Three nursing care delivery models, relationship-based care, the synergy model, and case management are briefly described next and depict how each model influences staffing management. Relationship-based care (RBC) is a common model used in care delivery (Koloroutis, 2004). Person (2004) articulated continuity of care as central to the RBC model, and this model also integrates Jean Watson’s theory of caring (Watson, 2002).

The synergy model for patient care is presented by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (Hardin & Kaplow, 2005). The core concept of the model is also based on the nurse-patient relationship and acknowledges that the needs or characteristics of the patients and families drive the competencies of the nurse. Synergy, or optimum outcomes, results when the needs and characteristics of the patient clinical unit, or system, are matched with a nurse’s competencies (Kaplow & Reed, 2008). Patient assignment technology may assist in defining, and therefore aligning, patient needs with the nurse’s abilities, a concept central to the model.

A third example is case management, defined by the Case Management Society of America (CMSA) as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” (CMSA, 2012, p. 1). Case management can be coupled with demand management to best coordinate care and resources to achieve positive patient outcomes, transitions of care coordination, and hospital reimbursement (Pickard & Warner, 2007).

Complementing these models, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) has recommended a new professional nurse role, the clinical nurse leader (CNL), into current care delivery models (AACN, 2003, 2007). The CNL role integrates various aspects of previous roles known in nursing, such as the case manager and clinical nurse specialist. The CNL vision statement is as follows: “The CNL champions innovations that improve patient outcomes, ensure quality care and reduce healthcare costs. The CNL integrates emerging nursing science into practice and leads this effort to enhance patient care. A recognized leader in all settings, the CNL is an advocate for reforming the healthcare delivery system and putting best practices into action” (AACN, 2003, p. 2).

American Organization of Nurse Executives

The American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE), a subsidiary of the American Hospital Association, is a national organization whose mission is to represent nurse leaders. More than a decade ago, this key leadership group published Staffing Management and Methods: Tools and Techniques for Nurse Leaders (AONE, 2000), which presents an introduction to evolving staffing measures. It has a chapter dedicated to staffing management approaches in each of four hospital types: the large academic medical center, an integrated health care system, a small community hospital, and a rural hospital setting. The final chapter discusses how various innovations in information systems support nurse staffing.

More recently, AONE’s 2008 Legislative Agenda for public policy and advocacy included several key points relevant to staffing management. The policy agenda aims to: “Develop, evaluate and support legislation that will foster the nurse executive’s leadership role in the management of the care environment, especially in areas related to staffing, information technology and patient care services” (AONE, 2008, p. 1). The agenda does not support mandates, such as overtime or staffing ratios, and recommends working with state and federal legislators to shape policies that promote flexibility and recognize the volatility of the patient care environment.

Staffing Recommendations by Professional Organizations

Several professional nursing specialty organizations have published position statements for nurse staffing to offer evidence-based guidelines for specialty practice. Nursing leaders in specialty practice should encourage identification and discussion of the position statement during the annual staffing plan review. For example, the National Association of Neonatal Nurses (1999a, b) has a staffing position statement and recommended staffing ratios that are also described in the “Guidelines for Perinatal Care” (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007). The ratios delineate care provided for women and newborns in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum settings, as well as the newborn nursery. In recently revised guidelines, the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN, 2010) describes the specific staffing recommendations for women in the various stages of normal labor and labor with complications.

Similarly, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN, 2005) has a position paper addressing key staffing issues in the operating room (OR), and the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA, 2003), has published recommendations for staffing. Finally, the American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN, 2005) has published an annotated bibliography summarizing the ambulatory nurse staffing literature. Haas and Hastings (2001) have outlined the methods for determining staffing requirements, skill mix, and productivity in the ambulatory care setting. Adoption of staffing recommendations in clinical settings by the relevant professional organizations is endorsed in the Principles of Nurse Staffing and frequently seen written into the staffing plans.

Collective Bargaining Agreements and Staffing Management

Provisions in the ANA Code of Ethics articulate the rights of nurses to address work conditions through collective action (ANA, 2010b). Porter (2010) described a successful model of professional practice labor partnerships. The two largest nursing and health care unions are (1) the United American Nurses (UAN), a branch of the ANA; and (2) the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) District 1199. Nursing unions are organizations that represent nurses for the purpose of collective bargaining, which has been defined as “the performance of the mutual obligations of the employer and the representative of the employees to meet at reasonable times and confer in good faith with respect to wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment…such obligation does not compel either party to agree to a proposal or require the making of a concession” (National Labor Relations Board, 2012, section 8b, paragraph 7d).

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

Legislative Impact on Staffing Management

Nurse dissatisfaction and concern for adequate staffing to provide quality nursing care to patients and their families arose from hospital cost-reduction initiatives throughout the 1990s. Armed with quality-of-care concerns, nurses began to organize and craft proposed staffing legislation in many states. The historical context that led to quality-of-care concerns continues to impact legislation today. Throughout the 1990s, hospital administrators relied on consultants to implement work redesign to promote patient-focused care as a method of cost reduction. The central labor reduction approach in patient-focused care was reducing the number of RNs and increasing the number of UAP. This approach for decreasing nursing RN skill mix was implemented in a “one size fits all” approach across organizations and often lacked evaluation of the skill mix change and other changes on the quality of care and nurse job satisfaction and retention (Eck, 1999; Norrish & Rundall, 2001). This was most apparent in California where a leaner RN skill mix was tried by Kaiser Permanente Northern California in the early 1990s. Skill mix was reduced from 55% RNs to 30% RNs in 1995 (Robertson & Samuelson, 1996). The changes in skill mix led to widespread real and perceived increases in RN workload, patient safety concerns, and nurse and consumer complaints (Norrish & Rundall, 2001; Seago et al., 2003).

Despite patient complaints and reports of nurse dissatisfaction, little was done until 1999. Only then did the California legislature pass Assembly Bill 394 (AB 394) to mandate minimum nurse staffing ratios and acuity adjusted staffing. The mandating of minimum nurse-to-patient ratios legislated in California ignited great debate, controversy, and study. Nurse scientists and policy experts have presented compelling arguments against mandated ratios and explicate that the local nursing leaders are in the best position to determine the actual staffing required by the particular patient population (Clarke, 2005). The bold action, however, of the California state legislative mandate stimulated focused attention on addressing nurse staffing issues.

Since the late 1990s, state legislation regarding nurse staffing issues has been commonplace, and over 25 states have various regulations. Primary trends of the enacted state legislation include limiting or precluding mandatory overtime, requiring staffing committees with direct-care nurse input, whistleblower protection, mandated public access to staffing information, and a requirement that implementation of patient acuity methodologies must adjust for staffing workload (White, 2006). State nurse staffing legislation has a significant impact on staffing management via regulation. The economic downturn in 2008 following the end of the Bush administration, however, shifted political attention to jobs and the economy and has stalled further legislative nurse staffing mandates.

THE STAFFING MANAGEMENT PLAN

The staffing management plan provides the structured processes to identify patient needs and then to deliver the staff resources as efficiently and effectively as possible. An effective plan first focuses on stabilizing the unit core staffing. A staffing pattern, or core coverage, is determined through a forecasted workload and a recommended care standard (e.g., HPPD). Hiring to the associated position complement and developing balanced and filled schedules, without holes, are essential building blocks for efficient and cost-effective daily resource allocation. Daily staffing allocation requires managing a variable staffing plan, measuring and predicting demand, and then providing balanced workload assignments to ensure that the correct caregivers are best matched to patient needs (Warner, 2006). A successful staffing management plan incorporates the policies inherent to the organization, patient care unit, and nurse population including union and contracting affiliations. Kane and colleagues (2007a, b) suggested that nurse staffing policies should address both patient care units and organizations, such as shift rotation, overtime, full-time/part-time mix, and weekend staffing. The traditional emphasis in staffing planning has been on hospital settings. However, with shifts to primary care as the predominant site, staffing planning is equally critical.

Forecasted Workload and Staffing Pattern (Core Coverage)

However, not all patients require the same number of care hours, and the total number of patient days may be inadequate for planning purposes. Finkler and colleagues (2007) suggested using adjusted units of service. For example, a nursing unit can be adjusted using a system for classifying patients, such as a patient acuity system, based on the resources each classification category is expected to use. Segregating patients into acuity classifications allows the staffing pattern to be developed based on the resource requirements of the specific mix of patients forecasted for the unit. Similar calculations can be made in ambulatory and primary care by using a method to classify patients into different categories to estimate the average resource required for patients in each category (Finkler et al., 2007).

1. Determine the number of paid hours per FTE.

2. Determine the percentage of productive hours to total paid hours.

3. Multiply the number of paid hours per FTE by the percentage of productive hours to find the number of productive hours per FTE.

4. Divide required care hours by productive hours per FTE to find the required number of FTEs.

5. Divide the required care hours by the number of days per year that the unit has patients to find care hours/day.

6. Divide that result by hours per shift to find the number of person shifts needed per working day.

7. Assign staff by employee type and among required shifts per day.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree