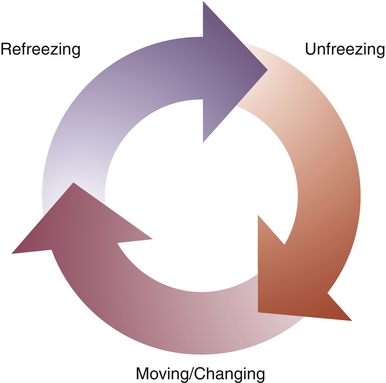

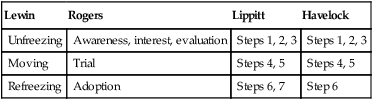

We participate in a world where change is all there is. We sit in the midst of continuous creation, in a universe whose creativity and adaptability are beyond comprehension. Nothing is ever the same twice, really. (Wheatley, 2007, p. 84) Change is inevitable in health care, just as it is in life. Nurses today are accustomed to change in their environments. Many have seen changes in the acuity of patients, changes in practice models and skill mixes, a change to evidence-based practice, changes in educational requirements, and changes within their own roles. Some nurses report that changes in practice are so frequent that they are taken for granted (Copnell & Bruni, 2006). Yet they also indicate that the very basis of nursing, providing care and support for patients, has not changed (Copnell & Bruni, 2006). Two approaches or models of change are found in the literature: planned change theories or models and emergent models (Shanley, 2007). Critiques of the planned approach highlight the prominence of its top-down approach and overemphasis on the role of managers in the process. In addition, the emphasis on cookbook-like approaches portrays change itself as linear rather than complex and multidimensional. In emergent approaches, the complex and multidimensional view of change is central. The emphasis is on principles or processes of change because there is little support for one particular strategy or number of steps being more effective than another (Shanley, 2007). Emerging views of change also emphasize the importance of the participatory process in change. Therefore, in this model, it is essential for nurse leaders to understand the role of the recipients in creating and sustaining change. Viewing change and resistance as two opposing forces can result in stereotyping one group as irrational resisters, rather than as partners in and co-creators of change. Change has long been a topic of interest to individuals and organizations. In the past, writings on organizational change emphasized a top-down planned change strategy. In most of these, the focus was on the role of administrators and top managers in the change process. Change was seen as initiated by administrators who formulate a plan for the change and communicate it to middle managers and others. Strategies for disseminating the change, informing staff, and dealing with resisters (often viewed as stubborn and irrational) are developed and implemented (Table 2-1 displays contrasting views of change). TABLE 2-1 Alternative views emerged that promoted the idea that top-down change is not just undesirable; it does not work (Balogun, 2006). Staff and other “recipients” of change must be viewed as integral to the process rather than as potential obstructions to be influenced and acted upon (Porter-O’Grady & Malloch, 2011). All levels need to be involved in planning for and sustaining change, and ideas for change can come from all levels. In addition, when considering the processes of change, issues of power and how individuals make sense of the change are essential. Evidence supports this emergent view of change (Shanley, 2007). There is little evidence in the literature showing whether any of the specific approaches to planned change actually work. There is evidence about what does work (Balogun, 2006). The literature points to the decreased importance of executives and increased importance of those affected by any change. The planned approach is too simplistic, takes too much for granted, and does not allow the analysis of the complex aspects of change over time. Two major types of change are applicable both to individuals and to organizations. They are first-order and second-order change. A classic book by Watzlawick and colleagues (1974) popularized the terms. In their definitions, a first-order change is one within a given system in which the system itself is unchanged. The terms first-order change and second-order change can be applied to individuals, small systems, and organizations. First-order change occurs in a stable system and is characterized by rational stepwise processes. It is seen as a method for maintaining stability in a system while making small incremental adjustments. First-order change is not seen as a vehicle for innovation, nor would it achieve organizational transformation (Alas, 2007). For an organization, it is adaptation based on monitoring the environment and making purposeful adjustments. At the industry level, this is evolution as a response to external forces such as markets. An example in nursing is when a new evidence-based protocol is developed and put into use in clinical practice. This is adaptation and adjustment. Second-order change is discontinuous and radical and occurs when fundamental properties or states of systems are changed. Second-order change calls for transformation, using innovation, new ideas, and creativity. In a second-order change, however, the occurrence changes the system itself. Watzlawick and colleagues (1974) found that second-order change often appears strange, unexpected, and even nonsensical. Organizational change has been defined as any modification in organizational composition, structure, or behavior (Bowditch & Buono, 2001). Most often, it refers to management efforts to move an organization from a current state to “some desired future state to increase organizational functioning” (Weimer et al., 2008, p. 381). These efforts are often described as planned change and involve top-down conception, communication, and implementation. Literature on organizational change is extensive. Lewin’s (1947, 1951) unfreezing, moving, and refreezing three stages of change theory is the classic model. In addition, newer approaches to organizational change, consistent with the emergent views, and can be found in the literature. In the 1990s, Senge (1990) introduced the idea of learning organizations. Learning organizations are ones that learn to adapt to change (Alas, 2007). How organizations adapt is related to their ability to be open, dynamic, and responsive to changes in the environment. The success of the learning organization is directly related to the people within the organization and their own learning. Workers need to be empowered themselves to be open and responsive to changes and to become “lifelong learners” (Senge et al., 1994). Within the learning organizations, Senge (1990) described the following five learning disciplines: • Personal mastery: Refers both to individual capacity to create desired results and to the creation of an environment or culture in which others can do the same • Mental models: How individuals develop, create, and project the personal vision they have of the world and understand how these personal views affect their decisions and actions • Shared vision: Sharing preferred future visions within a group for developing plans to get to that preferred future • Team learning: A sharing of learning skills and conversations so that the group can develop skills and learning greater than the individual parts • Systems thinking: Envisioning the organization as an interrelated system rather than unrelated parts Learning organizations are about change and helping people embrace change. Although Senge and colleagues (1994) noted that change and learning are certainly not synonymous, they believe they are clearly linked. Senge (1990) also emphasized that developing learning organizations equal to the challenges of today’s societal issues will require moving away from hierarchical leadership models and towards a new evolving idea of leadership. Anderson and Anderson (2009) also challenged hierarchical approaches to organizational change. They described how organizational leaders realized that traditional top-down, manager-driven approaches were no longer working. On encountering obstacles and resistance, leaders learned that they had to focus more on the process of change and human relationship aspects. Anderson and Anderson (2009) call the old way of viewing change as the industrial mind-set, and that organizational leaders need to move towards an emerging mindset. The industrial mindset is a mechanistic world view, relying on power and control, certainty and predictability. Anderson and Anderson (2009) identified the emerging mindset, like other complexity views, as one grounded in wholeness and relationship, embracing co-creation and participation. A component of this emerging mindset is that leaders need to move to what they call conscious change leadership. Conscious change leaders are aware of the dynamics of change and learn to lead from the principles of the emerging mindset. Conscious change leaders must be willing to look internally to transform their own mind-set, expand their thinking about process, and evolve their own leadership style. Nurse leaders, from the bedside to the executive suite, need to understand and be able to apply a variety of change theories. The majority of change theories originate from the work of Kurt Lewin. Most nurses have heard of Lewin and his three elements for a successful change: (1) unfreezing, (2) moving, and (3) refreezing (Figure 2-1). Since his work outlining the basic concepts of the change process was first published in 1947, it has been influential to those interested in change. It might be tempting to consider his ideas more consistent with the older, more traditional views of planned change (Burnes, 2004). However, Lewin was not only a remarkable thinker but also a humanitarian who believed that it was essential for democratic values to permeate all aspects of society. His model is also meant to help increase understanding about how groups and organizations change, and not as a rigid strategy to impose change. Lewin’s basic change process is still useful and applicable today and is the basis for many newer theories. Lewin coined the term planned change to distinguish the process from accidental or imposed change (Burnes, 2004). Lewin’s (1947, 1951) theory of change used ideas of equilibrium within systems. Unfreezing, the first stage of change, can be characterized as a process of “thawing out” the system and creating the motivation or readiness for change. An awareness of the need for change occurs. This first stage is cognitive exposure to the change idea, diagnosis of the problem, and work to generate alternative solutions. The unfreezing stage is considered to be finalized when those involved in the change process understand and generally accept the necessity of change. The second change stage is moving. This means proceeding to a new level of behavior, which implies that the actual visible change occurs in this stage. When the individuals involved collect enough information to clarify and identify the problem, the change itself can be planned and initiated. Lewin (1951) observed that a process of “cognitive redefinition,” or looking at the problem from a new perspective, happens. As a first step to launch a change, a pilot test may be done so that the change can be pretested and a transition period launched. Lewin’s (1947, 1951) planned change process stages can be compared to the nursing process and the generic problem-solving process (Table 2-2). Unfreezing is like assessing in the nursing process and like problem identification and definition in the problem-solving process. Moving is similar to planning and implementing in the nursing process and similar to problem analysis and seeking alternative solutions in the problem-solving process. Refreezing is like evaluation in the nursing process and like implementation and evaluation in the problem-solving process. TABLE 2-2 Similarities of Change, Nursing Process, and Problem Solving Data from Workman, R., & Kenney, M. (1988). The change experience. In S. Pinkerton, & P. Schroeder (Eds.), Commitment to excellence: Developing a professional nursing staff (pp. 17-25). Rockville, MD: Aspen. Individuals and systems naturally strive for equilibrium. Lewin (1951) saw this as a balance between driving forces that promote change and restraining forces that inhibit change. Both driving and restraining forces impinge on any situation. The relative strengths of these forces can be analyzed. To create change, the equilibrium is broken by altering the relative strengths of driving and restraining forces. A force field analysis facilitates the identification and analysis of driving and restraining forces in any situation. Unfreezing occurs when disequilibrium is introduced into the system to disrupt the status quo. Moving is the change to a new status quo. Refreezing occurs when the change becomes the new status quo and new behaviors are frozen. Lewin’s (1947, 1951) work forms the classic foundation for change theory. Other change theorists have elaborated further understanding and application of change theory. Bennis and colleagues (1961) assembled a book of readings on planned change that emphasized planner-adopter cooperation and high levels of adopter participation. Because actually implementing planned change is more dynamic and complex than Lewin’s model, Lippitt (1973) refined and expanded Lewin’s (1947, 1951) work on unfreezing, moving, and refreezing to identify the following seven phases of the change process that more fully describe planned change: 2. Assessment of motivation and capacity to change 3. Assessment of the change agent’s motivation and resources 4. Selecting progressive change objectives 5. Choosing an appropriate role for the change agent 6. Maintaining the change once it is started 7. Termination of the helping relationship with the change agent The first three steps can be compared to Lewin’s unfreezing (1947, 1951). Steps 4 and 5 match moving, and steps 6 and 7 are comparable to refreezing. Similar to Lippitt (1973), Havelock (1973) listed the following six elements in the process of planned change: The first three steps correspond to the unfreezing stage of change, the fourth and fifth are similar to the moving stage, and the last relates to refreezing. The various conceptualizations of the stages of the process of change bear similarity to one another but vary in emphasis (Table 2-3). TABLE 2-3 Comparisons of the Process of Change Theories Change and innovation are companion terms, but innovation has been differentiated from change by many authors over time. Change is a disruption; innovation is the use of change to provide some new product or service (Romano, 1990). An innovation is defined as something new—the introduction of a new process or new way of doing something. Innovation also has been viewed as the use of a new idea to solve a problem (Kanter, 1983). Kanter (1983) said that innovation refers to the process of bringing any new or problem-solving idea into use. Innovation is often linked with creativity. Organizations need to promote environments that encourage creativity and opportunities for innovation (Hughes, 2006). Leaders are essential to innovation because they must help create the environment and opportunities for innovation. Innovation is a complex phenomenon. It is of interest in many fields from business to science, and, of course, in health care. In some views, innovation is considered a radical act, such as the introduction of a new product or process (Aranda & Molina-Fernandez, 2002). Others, such as Drucker (1992), believe that it can be a purposeful and systematic use of opportunity from changes in the economy, technology, and demographics. In this view, innovation is systematic, takes hard work, and has little to do with genius and inspiration. A purposeful and organized search for change is the basis for systematic innovation. A careful analysis of the opportunities for change is the best hope for successful economic or social innovation. This occurs because successful innovations exploit change. Drucker noted that the challenge is to make institutions capable of innovation; innovation depends on “organized abandonment” (1992, p. 340). This is a process of eliminating the obsolete and the no longer productive efforts of the past. A willingness to view change as an opportunity is needed. 1. First knowledge of an innovation’s existence and functions 2. Persuasion to form an attitude toward the innovation 3. Decision to adopt or reject 4. Implementation of the new idea 5. Confirmation to reinforce or reverse the innovation decision 1. Relative advantage: The degree to which the change is thought to be better than the status quo 2. Compatibility: The degree to which the change is compatible with existing values of the individuals or group 3. Complexity: The degree to which a change is perceived as difficult to use and understand 4. “Trialability”: The degree to which a change can be tested out on a limited basis 5. “Observability”: The degree to which the results of a change are visible to others

Change and Innovation

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

BACKGROUND

Planned Change (Traditional View)

Emergent View

Direction

Top-down, linear

Multidirectional, multidimensional

Initiator

Leader initiated

Diffuse

Process

Planned, step-by-step process

Principles to guide process

Organizational culture

May be considered

Essential to consider

Power issues

Not considered, or not spoken

Essential to consider

Role of staff/recipients of change

Resisters

Participants in change process

View of the change recipients

May be assessed so they can be changed or manipulated

Essential to process

PERSPECTIVES ON CHANGE

Types of Change

Organizational Change

CHANGE THEORIES

Lewin’s Change Process

Change

Nursing Process

Problem Solving

Unfreezing

Assessing

Problem identification and definition

Moving

Planning and implementing

Problem analysis and seeking alternatives

Refreezing

Evaluation

Implementation and evaluation

Lewin

Rogers

Lippitt

Havelock

Unfreezing

Awareness, interest, evaluation

Steps 1, 2, 3

Steps 1, 2, 3

Moving

Trial

Steps 4, 5

Steps 4, 5

Refreezing

Adoption

Steps 6, 7

Step 6

Innovation Theory

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Change and Innovation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access