Spiritual Health

Objectives

• Discuss the influence of spiritual practices on the health status of patients.

• Describe the relationship among faith, hope, and spiritual well-being.

• Compare and contrast the concepts of religion and spirituality.

• Perform an assessment of a patient’s spirituality.

• Discuss nursing interventions designed to promote spiritual health.

• Establish presence with patients.

Key Terms

Agnostic, p. 692

Atheist, p. 692

Connectedness, p. 692

Faith, p. 693

Holistic, p. 702

Hope, p. 693

Self-transcendence, p. 692

Spiritual distress, p. 693

Spirituality, p. 691

Spiritual well-being, p. 692

Transcendence, p. 692

![]()

The word spirituality derives from the Latin word spiritus, which refers to breath or wind. The spirit gives life to a person. It signifies whatever is at the center of all aspects of a person’s life (Smith, 2008). Florence Nightingale believed that spirituality was a force that provided energy needed to promote a healthy hospital environment and that caring for a person’s spiritual needs was just as essential as caring for his or her physical needs (Dolamo, 2010). Today spirituality is often defined as an awareness of one’s inner self and a sense of connection to a higher being, nature, or some purpose greater than oneself (Smith, 2008; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009). A person’s health depends on a balance of physical, psychological, sociological, cultural, developmental, and spiritual factors. Spirituality is important in helping individuals achieve the balance needed to maintain health and well-being and cope with illness. Research shows that spirituality positively affects and enhances health, quality of life, health promotion behaviors, and disease prevention activities (Jurkowski, Kurlanska, and Ramos, 2010; Lee, 2009).

Too often nurses and other health care providers fail to recognize the spiritual dimension of their patients because spirituality is not scientific enough, it has many definitions, and it is difficult to measure. In addition, some nurses and health care providers do not believe in God or an ultimate being, some are not comfortable with discussing the topic, and others claim that they do not have time to address spiritual needs (Tanyi, McKenzie, and Chapek, 2009). The concepts of spirituality and religion are often interchanged, but spirituality is a much broader and more unifying concept than religion (Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

The human spirit is powerful, and spirituality has different meanings for different people (Pesut et al., 2008). Therefore nurses need to be aware of their own spirituality to provide appropriate and relevant spiritual care to others. They need to care for the whole person and accept a patient’s beliefs and experiences when providing spiritual care (Ellis and Narayanasamy, 2009; Mueller, 2010). Being able to determine the importance that spirituality holds for patients depends on a nurse’s ability to develop a caring relationship (see Chapter 7). Nursing care involves helping patients use their spiritual resources as they identify and explore what is meaningful in their lives and find ways to cope with the impact of illness and the ongoing stressors of life.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The relationship between spirituality and healing is not completely understood. However, the individual’s intrinsic spirit seems to be an important factor in healing. Healing often takes place because of believing. Current evidence shows a link between mind, body, and spirit. An individual’s beliefs and expectations often have effects on his or her physical and psychological well-being (Burris et al., 2009). Many of these effects are tied to hormonal and neurological function. For example, relaxation exercises and guided imagery improve immune function in certain situations (Lahmann et al., 2010; Weigensberg et al., 2009) and reduce perceptions of pain and anxiety (Casida and Lemanski, 2010). Laughter raises pain thresholds, boosts the immune system, reduces stress and anxiety, relieves tension, and elevates mood (Harkins 2009; Swetz et al., 2009). A person’s inner beliefs and convictions are powerful resources for healing. Nurses who support the spirituality of patients and their families are successful in helping patients achieve desirable health outcomes.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nursing research shows the association between spirituality and health. For example, Pierce et al. (2008) found that caregivers used spirituality to cope with the daily aspects of providing care to family members who have had strokes. Hollywell and Walker (2009) found that prayer often helps those who attend church or who are older, female, or less educated cope with chronic illnesses and maintain feelings of well-being. The increased interest in studying the relationship between spirituality and health has greatly contributed to nursing science.

Current Concepts in Spiritual Health

A variety of concepts describe spiritual health. To provide meaningful and supportive spiritual care, it is important to understand the concepts of spirituality, spiritual well-being, faith, religion, and hope. Each concept offers direction in understanding the views that individuals have of life and its value.

Spirituality

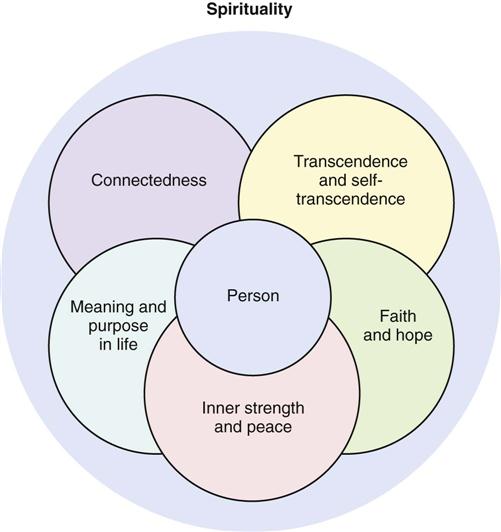

Spirituality is a complex concept that is unique to each individual; it depends on a person’s culture, development, life experiences, beliefs, and ideas about life (McSherry, 2007). Furthermore, spirituality is an inherent human characteristic that exists in all people, regardless of their religious beliefs. It gives individuals the energy needed to discover themselves, cope with difficult situations, and maintain health (Villagomeza, 2006). Energy generated by spirituality helps patients feel well and guides choices made throughout life. Spirituality enables a person to love, have faith and hope, seek meaning in life, and nurture relationships with others. Because it is subjective, multidimensional, and personal, researchers and scholars cannot agree on a universal definition of spirituality (Tanyi, McKenzie, and Chapek, 2009). However, five distinct but overlapping constructs are frequently found in definitions of spirituality (Fig. 35-1).

Self-transcendence is a sense of authentically connecting to one’s inner self (Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009), whereas transcendence is the belief that a force outside of and greater than the person exists beyond the material world (Bailey et al., 2009). Individuals usually see this force as positive, and it allows people to have new experiences and develop new perspectives that are beyond ordinary physical boundaries. Examples of transcendent moments include the feeling of awe when holding a new baby or looking at a beautiful sunset. Spirituality offers a sense of connectedness intrapersonally (connected within oneself), interpersonally (connected with others and the environment), and transpersonally (connected with the unseen, God, or a higher power). Through connectedness patients are able to move beyond the stressors of everyday life and find comfort, faith, hope, peace, and empowerment (Nelson-Becker, Nakashima, and Canda, 2007). Faith allows people to have firm beliefs despite lack of physical evidence. It enables them to believe in and establish transpersonal connections. Although many people associate faith with religious beliefs, it exists without religious beliefs (Villagomeza, 2006). Hope has several meanings that vary on the basis of how it is being experienced; it usually refers to an energizing source that has an orientation to future goals and outcomes (Phillips-Salimi et al., 2007; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

Spirituality gives people the ability to find a dynamic and creative sense of inner strength that is often used when making difficult decisions. Inner strength is a source of energy that instills hope, provides motivation, and promotes a positive outlook on life (Lundman et al., 2010). Inner peace fosters calm, positive, and peaceful feelings despite life experiences of chaos, fear, and uncertainty. These feelings help people feel comforted even in times of great distress (Hanson et al., 2008). Spirituality also helps people find meaning and purpose in life in both positive and negative life events (Bailey et al., 2009; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

Some people do not believe in the existence of God (atheist) or they believe that there is no known ultimate reality (agnostic). This does not mean that spirituality is not an important concept for the atheist or agnostic (Smith-Stoner, 2007). Atheists search for meaning in life through their work and their relationships with others. Agnostics discover meaning in what they do or how they live because they find no ultimate meaning for the way things are. They believe that people bring meaning to what they do.

Spirituality is an integrating theme. A person’s concept of spirituality begins in childhood and continues to grow throughout adulthood (Narayanasamy et al., 2004; Smith and McSherry, 2004). It represents the totality of one’s being, serving as the overriding perspective that unifies the various aspects of an individual. It spreads through all dimensions of a person’s life, whether or not the person acknowledges or develops it.

Spiritual Well-Being

The concept of spiritual well-being is often described as having two dimensions. The vertical dimension supports the transcendent relationship between a person and God or some other higher power. The horizontal dimension describes positive relationships and connections that people have with others (Gray, 2006; Smith, 2006). Spiritual well-being has a positive effect on health. Those who experience spiritual well-being feel connected to others and are able to find meaning or purpose in their lives. Spiritual well-being leads to spiritual health. Those who are spiritually healthy experience joy, are able to forgive themselves and others, accept hardship and mortality, report an enhanced quality of life, and have a positive sense of physical and emotional well-being (Whelan-Gales et al., 2009; Yampolsky et al., 2008).

Faith

In addition to being a part of the definition of spirituality, the concept of faith has other common definitions. Faith is a cultural or institutional religion such as Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, or Christianity. It is also a relationship with a divinity, higher power, authority, or spirit that incorporates a reasoning faith (belief) and a trusting faith (action). Reasoning faith provides confidence in something for which there is no proof. It is an acceptance of what reasoning cannot explain. Sometimes faith involves a belief in a higher power, spirit guide, God, or Allah. Faith is also the manner in which a person chooses to live. It gives purpose and meaning to an individual’s life, allowing for action. Many times patients who are ill have a positive outlook on life and continue to pursue daily activities rather than resign themselves to the symptoms of the disease. Their faith often becomes stronger because they view their illness as an opportunity for personal growth (Alcorn et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2010).

Religion

Religion is associated with the “state of doing,” or a specific system of practices associated with a particular denomination, sect, or form of worship. Religion refers to the system of organized beliefs and worship that a person practices to outwardly express spirituality. Many people practice a faith or belief in the doctrines and expressions of a specific religion or sect such as the Lutheran church or Orthodox Judaism. People from different religions view spirituality differently. For example, a Buddhist believes in Four Noble Truths: life is suffering; suffering is caused by clinging; suffering can be eliminated by eliminating clinging; and to eliminate clinging and suffering, one follows an eightfold path. The path includes right understanding, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. It promotes wisdom, moral behavior, and meditation (Wilkins, Mailoo, and Kularatne, 2010). A Buddhist turns inward, valuing self-control, whereas a Christian looks to the love of God to provide enlightenment and direction in life.

When providing spiritual care to a patient, it is important to understand the differences between religion and spirituality. Many people tend to use the terms spirituality and religion interchangeably. Although closely associated, these terms are not synonymous. Religious practices encompass spirituality, but spirituality does not need to include religious practice. Religious care helps patients maintain their faithfulness to their belief systems and worship practices. Spiritual care helps people identify meaning and purpose in life, look beyond the present, and maintain personal relationships and a relationship with a higher being or life force.

Hope

Spirituality and faith bring hope. When a person has the attitude of something to live for and look forward to, hope is present. It is a multidimensional concept that provides comfort while people endure life-threatening situations, hardships, and other personal challenges. It is closely associated with faith and is energizing, giving individuals a motivation to achieve and the resources to use toward that achievement. People express hope in all aspects of their lives to help them deal with life stressors. Hope is a valuable personal resource whenever someone is facing a loss (see Chapter 36) or a difficult challenge (Duggleby, Cooper, and Penz, 2009).

Spiritual Health

People gain spiritual health by finding a balance between their values, goals, and beliefs and their relationships within themselves and others. Throughout life a person often grows more spiritual, becoming increasingly aware of the meaning, purpose, and values of life. In times of stress, illness, loss, or recovery, a person often uses previous ways of responding or adjusting to a situation. Often these coping styles lie within the person’s spiritual beliefs.

Spiritual beliefs change as patients grow and develop. Spirituality begins as children learn about themselves and their relationships with others. Nurses who understand a child’s spiritual beliefs are able to care for and comfort the child (Mueller, 2010). As children mature into adulthood, they experience spiritual growth by entering into lifelong relationships. An ability to care meaningfully for others and self is evidence of a healthy spirituality.

Beliefs among older people vary based on many factors such as gender, past experience, religion, economic status, and ethnic background. Healthy spirituality in older adults is one that gives peace and acceptance of the self. It is often based on a lifelong relationship with a Supreme Being. Illness and loss sometimes threaten and challenge the spiritual developmental process. Older adults often express their spirituality by turning to important relationships and giving of themselves to others (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Factors Influencing Spirituality

When illness, loss, grief, or a major life change occurs, either people use spiritual resources to help them cope or spiritual needs and concerns develop. Spiritual distress is the “impaired ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself” (NANDA International, 2011). Spiritual distress causes a person to feel doubt, loss of faith, and a sense of being alone or abandoned. Individuals often question their spiritual values, raising questions about their way of life, purpose for living, and source of meaning. Spiritual distress also occurs when there is conflict between a person’s beliefs and prescribed health regimens or the inability to practice usual rituals.

Acute Illness

Sudden, unexpected illness frequently creates significant spiritual distress. For example, both the 50-year-old patient who has a heart attack and the 20-year-old patient who is in a motor vehicle accident face crises that threaten their spiritual health. The illness or injury creates an unanticipated scramble to integrate and cope with new realities (e.g., disability). People often look for ways to remain faithful to their beliefs and value systems. Some pray, attend religious services more often, or spend time reflecting on the positive aspects of their lives. Often conflicts develop around a person’s beliefs and the meaning of life. Anger is common; and patients sometimes express it against God, their families, themselves, or the nurse. The strength of a patient’s spirituality influences how he or she copes with sudden illness and how quickly he or she moves to recovery. Nurses use knowledge of a person’s spiritual well-being and implement spiritual interventions to maximize inner peace and healing (Yeager et al., 2010).

Chronic Illness

Many chronic illnesses threaten the person’s independence, causing fear, anxiety, and spiritual distress. Dependence on others for routine self-care needs often creates feelings of powerlessness. Powerlessness and the loss of a sense of purpose in life impair the ability to cope with alterations in functioning. Spirituality significantly helps patients and their family caregivers adapt to the changes that result from chronic illness (Box 35-1). Successful adaptation often provides spiritual growth. Patients who have a sense of spiritual well-being, feel connected with a higher power and others, and are able to find meaning and purpose in life are better able to cope with and accept their chronic illness (Daaleman and Dobbs, 2010; Ebadi et al., 2009).

Terminal Illness

Terminal illness commonly causes fears of physical pain, isolation, the unknown, and dying. It creates an uncertainty about what death means, making patients susceptible to spiritual distress. However, some patients have a spiritual sense of peace that enables them to face death without fear. Spirituality helps these patients find peace in themselves and their death. Individuals experiencing a terminal illness often find themselves reviewing their life and questioning its meaning. Common questions they ask include “Why is this happening to me?” or “What have I done?” Terminal illness often affects family and friends just as much as the patient. It causes members of the family to ask important questions about its meaning and how it will affect their relationship with the patient (see Chapter 36). In addition to managing patients’ physical and psychosocial symptoms experienced at the end of life, empower them to have a greater sense of control over their disease, regardless of whether they receive care in a hospital or at home. Providing holistic care is essential because dying is a part of life that encompasses the patient’s physical, social, psychological, and spiritual health (Wasserman, 2008).

Near-Death Experience

Some nurses care for patients who have had a near-death experience (NDE). An NDE is a psychological phenomenon of people who either have been close to clinical death or have recovered after being declared dead. It is not associated with a mental disorder. Persons who experience an NDE often tell the same story of feeling themselves rising above their bodies and watching caregivers initiate lifesaving measures. Most individuals describe passing through a tunnel to a bright light, encountering people who had preceded them in death, and feeling an inner tranquility and peace. Instead of moving toward the light, they learn that it is not time for them to die, and they return to life (Rominger, 2010).

Patients who have an NDE are often reluctant to discuss it, thinking that others will not understand. However, individuals experiencing an NDE who discuss it with family or caregivers find acceptance and meaning from this powerful experience. They are often no longer afraid of death. After a patient has survived an NDE, it is important to remain open and give him or her a chance to explore what happened. Provide support if the patient decides to share the experience with significant others (Duffy, 2007).

Critical Thinking

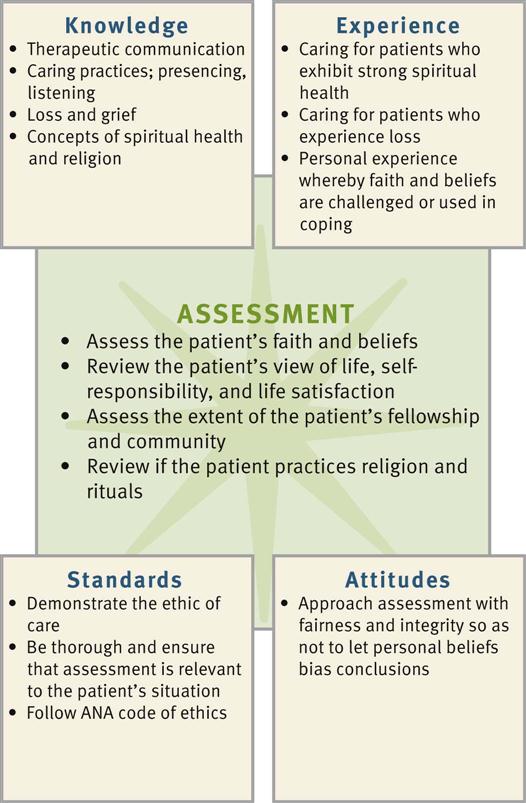

The helping role is important in nursing practice (Benner, 1984). Patients look to nurses for help that is different than the help they seek from other health care professionals. Expert nurses acquire the ability to anticipate personal issues affecting patients and their spiritual well-being. Critical thinking, knowledge, and skills help nurses enhance patients’ spiritual well-being and health. While using the nursing process, apply knowledge, experience, attitudes, and standards in providing appropriate spiritual care (Fig. 35-2). Nurses who are comfortable with their own spirituality often are more likely to care for their patients’ spiritual needs. Nurses who foster their own personal, emotional, and spiritual health become resources for their patients and use their own spirituality as a tool when caring for themselves and their patients (Chism and Magnan, 2009; Ellis and Narayanasamy, 2009).

Taking a faith history reveals patient’s beliefs about life, health, and a Supreme Being. Knowing patients’ cultural preferences provides additional insight into their spiritual practices. Applying knowledge of spiritual concepts, principles of caring (see Chapter 7), and therapeutic communication skills (see Chapter 24) helps nurses readily recognize and understand patients’ spiritual needs. Convey caring and openness to successfully promote honest discussion about patients’ spiritual beliefs.

A sound understanding of ethics and values (see Chapter 22) is essential when providing spiritual care. A person’s values or beliefs about the worth of a given idea, attitude, or custom are linked to his or her spiritual well-being. Application of ethical principles ensures respect for a patient’s spiritual and religious convictions.

Personal experience in caring for patients in spiritual distress is valuable when helping patients select coping options. You need to determine if your spirituality is beneficial in assisting patients. Nurses who sense a personal faith and hope regarding life are usually better able to help their patients. Previous personal and professional experiences with dying patients, patients with chronic disease, or those who have experienced significant losses provide lessons in how to help patients face difficult challenges and how to offer support to family and friends.

Because each person has a unique spirituality, you need to know your own beliefs so you are able to care for each patient without bias (Tiew and Creedy, 2010). Use critical thinking when assessing each patient’s reaction to illness and loss and when determining if spiritual intervention is necessary. Humility is essential, especially when caring for patients from diverse cultural and/or religious backgrounds. Recognize personal limitations in knowledge about patients’ spiritual beliefs and religious practices. Effective nurses show genuine concern as they assess their patients’ beliefs and determine how spirituality influences their patients’ health. You demonstrate integrity by refraining from voicing your opinions about religion or spirituality when your beliefs conflict with those of your patients.

The application of intellectual standards helps you make accurate clinical decisions and helps patients find meaningful and logical ways to acquire spiritual healing. Critical thinking ensures that you obtain significant and relevant information when making decisions about patients’ spiritual needs. The nature of a person’s spirituality is complex and highly individualized. Therefore avoid making assumptions about his or her religion and beliefs. Significance and relevance are standards of critical thinking that ensure that you explore the issues that are most meaningful to patients and most likely to affect spiritual well-being.

In setting standards for quality health care, The Joint Commission (2010) requires health care organizations to assess patients’ denomination, beliefs, and spiritual practices and acknowledge their rights to spiritual care. Health care organizations also need to provide for patients’ spiritual needs through pastoral care or others who are certified, ordained, or lay individuals.

The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses (Fowler, 2010) requires nurses to practice nursing with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each patient despite socioeconomic status, personal characteristics, or type of health problem. It is essential to promote an environment that respects patients’ values, customs, and spiritual beliefs. Routinely implementing nursing interventions such as prayer or meditation is coercive and/or unethical. Therefore determine which interventions are compatible with the patient’s beliefs and values before selecting them. An ethic of caring (see Chapter 22) provides a framework for decision making and places the nurse as the patient’s advocate.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to use to develop and implement an individualized plan of care. The core of nursing includes a commitment to caring and respect for an individual’s uniqueness. Application of the nursing process from the perspective of a patient’s spiritual needs is not simple. It goes beyond assessing his or her religious practices. Understanding a patient’s spirituality and then appropriately identifying the level of support and resources needed require a compassionate perspective. Remove any personal biases or misconceptions from patient assessments and be willing to share and discover another person’s meaning and purpose in life, illness, and health. Love, trust, hope, forgiveness, meaning, and community are universal spiritual needs. Learning to share these needs helps you find a way to give patients spiritual care and support. Patients bring certain spiritual resources that help them assume healthier lives, recover from illness, or face impending death. Supporting and recognizing the positive side of a patient’s spirituality goes a long way toward delivering effective, individualized nursing care.

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Because spirituality is deeply subjective, it means different things to different people (Bailey et al., 2009).

Through the Patient’s Eyes

It is essential to take the time to assess the patient’s viewpoints and establish a trusting relationship with him or her. Focus nursing assessment on aspects of spirituality that life experiences and events most likely influence. As you and your patients reach a point of learning together, spiritual caring occurs.

Spiritual assessment is therapeutic because it expresses a level of caring and support. It is also a fundamental part of the nursing assessment. Because completing a spiritual assessment takes time, conduct an ongoing assessment over the course of the patient’s stay in the health care setting if possible. Establish trust and rapport and make the opportunity to conduct meaningful discussions with patients a priority.

You can assess a patient’s spiritual health in several different ways. One way is to ask direct questions (Box 35-2). This approach requires you to feel comfortable asking others about their spirituality. Several assessment tools are available to help nurses clarify values and assess spirituality. For example, the spiritual well-being (SWB) scale has 20 items that assess the individual’s view of life and relationship with a higher power (Gray, 2006). The B-E-L-I-E-F assessment tool helps nurses evaluate a child’s and family’s spiritual and religious needs (McEvoy, 2003). The acronym stands for the following:

Effective spiritual assessment tools such as the SWB and B-E-L-I-E-F help nurses remember important areas to assess. A patient’s response to items on assessment tools often indicates areas that need further investigation. For example, if after using an assessment tool, a nurse finds that a patient has difficulty accepting change, the nurse needs to spend time understanding how the patient is accepting and managing the new illness. Whether you use an assessment tool or direct an assessment with questions that are based on principles of spirituality, it is important not to impose your personal value systems on the patient. This is particularly true when the patient’s values and beliefs are similar to those of your own because it then becomes very easy to make false assumptions. When nurses understand the overall approach to spiritual assessment, they are able to enter into thoughtful discussions with their patients, gain a greater awareness of the personal resources that patients bring to a situation, and incorporate the resources into an effective plan of care.

Faith/Belief

Assess the source of authority and guidance that patients use in life to choose and act on their beliefs. Determine if the patient has a religious source of guidance that conflicts with medical treatment plans and affects the option that nurses and other health care providers are able to offer patients. For example, if a patient is a Jehovah’s Witness, blood products are not an acceptable form of treatment. Christian Scientists often refuse any medical intervention, believing that their faith heals them. It is also important to understand a patient’s philosophy of life. Assessment data reveal the basis of the patient’s belief system regarding meaning and purpose in life and the patient’s spiritual focus. This information often reflects the impact that illness, loss, or disability has on the person’s life. Considerable religious diversity exists in the United States. A patient’s religious faith and practices, views about health, and the response to illness often influence how nurses provide support (Table 35-1).

TABLE 35-1

Religious Beliefs About Health

| RELIGIOUS OR CULTURAL GROUP | HEALTH CARE BELIEFS | RESPONSE TO ILLNESS | IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH AND NURSING |

| Hinduism | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|