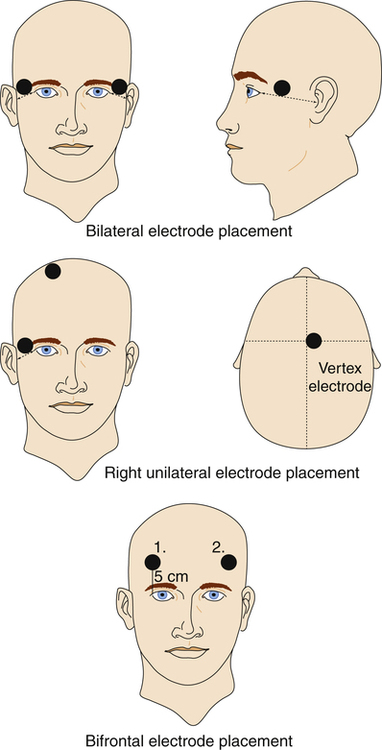

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d, Pluck from the memory rooted sorrow, Raze out the written troubles of the brain, And with some sweet oblivious antidote Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of the perilous stuff 1. Analyze the use, indications, mechanism of action, and adverse effects of convulsive therapies (electroconvulsive therapy [ECT] and magnetic seizure therapy) as treatment strategies for psychiatric illness. 2. Discuss the nursing care needs of the patient receiving ECT. 3. Analyze the use, indications, mechanism of action, and adverse effects of chronotherapy (phototherapy, sleep deprivation) as treatment strategies for psychiatric illness. 4. Analyze the use, indications, mechanism of action, and adverse effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and implantable brain stimulation devices as treatment strategies for psychiatric illness. 5. Analyze the use, indications, mechanism of action, and adverse effects of implantable brain stimulation devices (vagus nerve stimulation and deep brain stimulation) as treatment strategies for psychiatric illness. Nurses provide care to patients receiving somatic therapies and it is essential that all nurses understand how these treatments work. This includes an understanding of nursing care that enhances their effectiveness. This chapter discusses some of the most current somatic therapies used for psychiatric illnesses (Higgins and George, 2009). Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was first described in 1938 as a treatment for schizophrenia, when it was believed that people with epilepsy were rarely schizophrenic, and it was thought that convulsions could cure schizophrenia. This was not supported by later research. ECT is actually more effective for mood disorders than for schizophrenia (Payne and Prudic, 2009a). • Electroconvulsive therapy is a treatment in which a grand mal seizure is artificially induced in an anesthetized patient by passing an electrical current through electrodes applied to the patient’s head (Mankad et al, 2010). • Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) is a newer form of treatment that uses a magnetic current instead of electricity. MST has been developed based on the ECT model. It uses a magnetic stimulus to produce controlled seizures in selected regions of the brain. It was developed in an effort to reduce seizure spread to medial temporal structures, thus limiting cognitive side effects (Kayser et al, 2009; Cycowicz et al, 2009). Clinical experience with MST is still limited, and current studies are exploring its antidepressant efficacy. Traditionally electrodes in ECT have been applied bilaterally. Alternative electrode placements are now routinely used, including bifrontal and unilateral. Patients have equal effectiveness and fewer cognitive side effects with these alternative placements, including less disorientation and fewer disturbances of verbal and nonverbal memory (Sackeim et al, 2008; Peterchev et al, 2010). Studies of a new form of unilateral ECT, called focal electrically administered seizure therapy (FEAST) appears to minimize cognitive effects of ECT even further (Pierce et al, 2008). Figure 29-1 illustrates the different electrode placements. ECT is an effective psychiatric treatment and is generally well tolerated by patients. In some cases, after a successful initial course of treatment, maintenance ECT plus antidepressant medication is recommended: weekly treatments for the first month after remission, gradually tapering to monthly (APA, 2001). The primary indication for ECT is major depression (Weiner and Falcone, 2011). Some see it as the gold standard for treatment-resistant depression (Nahas and Anderson, 2011). ECT’s response rate of 80% or more for most patients is better than response rates for antidepressant medications, and is considered to be the most effective antidepressant in use (Keltner and Boschini, 2009). It can be used for people in most age-groups who cannot tolerate or fail to respond to treatment with medication. Box 29-1 lists the primary and secondary criteria for the use of ECT as determined by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Task Force on Electroconvulsive Therapy. Finally, ECT should be an initial intervention when its anticipated side effects are considered less harmful than those associated with drug therapy in populations such as the elderly, patients with heart block, and women who are pregnant. The potential effectiveness of ECT is reduced in those with personality disorders. Box 29-2 summarizes behaviors for which ECT is and is not effective. • Neurotransmitter theory suggests that ECT acts like tricyclic antidepressants by enhancing deficient neurotransmission in monoaminergic systems. Specifically, it is thought to improve dopaminergic, serotonergic, and adrenergic neurotransmission. • Neurotrophic factor theory suggests that cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) is up-regulated with ECT, which increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF regulates neuronal cell growth and is also involved in norepinephrine and serotonin receptor expression. • Anticonvulsant theory suggests that ECT treatment exerts a profound anticonvulsant effect on the brain that results in an antidepressant effect. Some support for this theory is based on the fact that a person’s seizure threshold rises over the course of ECT and that some patients with epilepsy have fewer seizures after receiving ECT. The mortality rate associated with ECT is estimated to be the same as that associated with general anesthesia in minor surgery (approximately 2 to 10 deaths per 100,000 treatments) (Payne and Prudic, 2009b). Mortality and morbidity are believed to be lower with ECT than with the administration of antidepressant medications. • Cardiovascular: Transient cardiovascular changes are expected in ECT. Routine electrocardiograms (ECGs) are performed to rule out baseline pathology, with further work-up as indicated. • Systemic: Headaches, nausea, muscle soreness, and drowsiness may occur after ECT, but usually respond to supportive management and nursing intervention. • Cognitive: ECT is associated with a range of cognitive side effects, including confusion immediately after the seizure and memory disturbance during the treatment course, although a few patients report persistent deficits. The onset of cognitive side effects varies considerably among patients. Patients with preexisting cognitive impairment, those with neuropathological conditions, and those receiving psychotropic medication during ECT are at increased risk of developing side effects. No evidence has been found to indicate that ECT causes brain damage (McClintock and Husain, 2011). As the patient reveals these fears and concerns, the nurse can clarify misconceptions and emphasize the therapeutic value of the procedure. Supporting the patient and family is an essential part of nursing care before, during, and after treatment (Payne and Prudic, 2009b). Before ECT treatment begins, an informed consent form must be signed by the patient or, if the patient does not have the capacity to give consent, by a legally designated person (Chapter 8). This consent acknowledges the patient’s rights to obtain or refuse treatment. Although it is the physician’s ultimate responsibility to explain the procedure when obtaining consent, the nurse plays an important part in the consent process (Fetterman and Ying, 2011). The treatment nurse is responsible for ensuring proper preparation of the treatment suite. Box 29-3 provides a list of standard equipment needed to provide optimal patient care. A crash cart with defibrillator should be readily available for emergency use.

Somatic Therapies

Convulsive Therapies

Indications

Mechanism of Action

Adverse Effects

Nursing Care

Emotional Support and Education

Pretreatment Nursing Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Somatic Therapies

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access