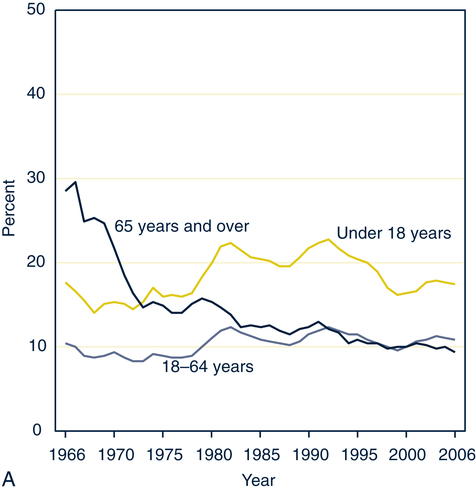

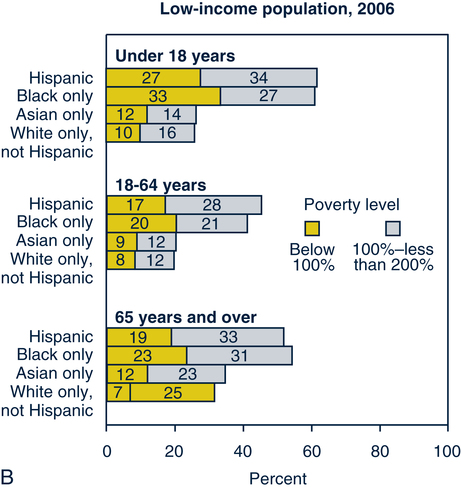

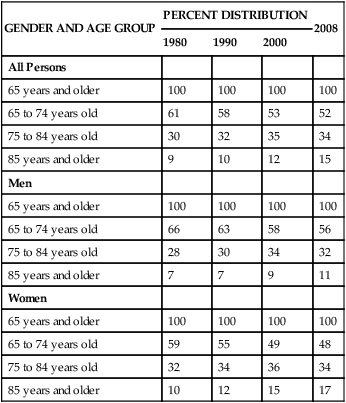

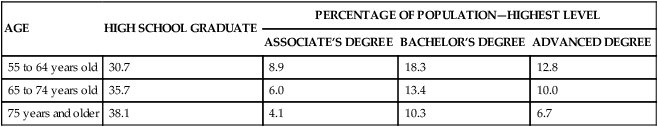

Sue E. Meiner, EdD, APRN, BC, GNP On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify the major socioeconomic and environmental factors that influence the health of older adults. 2. Explain the importance of age cohorts in understanding older adults. 3. Describe the economic factors that influence the lives of older persons. 4. Identify components of the Medicare health insurance programs. 5. Discuss the influence of support systems on the health and well-being of older adults. 6. Distinguish between a conservator, guardian, and durable power of attorney. 7. Discuss environmental factors that affect the safety and security of older adults. 8. Compare and contrast the housing options available for older adults. 9. Compare the influences of income, education, and health status on quality of life. 10. Relate strategies for protecting older persons in the community from criminal victimization. 11. Assess the ability of older adults to be their own advocate. Socioeconomic factors such as income, level of education, present health status, and availability of support systems all affect the way older adults perceive the health care system. Benefits and entitlements may influence the availability of high-quality health care. A small number of older adults may not be competent to manage their own health care; they need the protection of a conservator or guardian (see Chapter 3). Environmental factors such as geographic area, housing, perceived criminal victimization, and community resources make a difference in older adults’ abilities to obtain the type and quality of health care that is appropriate. One of the strongest and most consistent predictors of illness and death is socioeconomic status (Krause, 1997). The environment also influences safety and well-being. Therefore it is imperative that health care professionals understand the socioeconomic and environmental status of older adults. Although, in some cases, illness can lead to poverty, more often poverty causes poor health by its connection with inadequate nutrition, substandard housing, exposure to environmental hazards, unhealthy lifestyles, and decreased access to and use of health care services. In 2008 research found that the nation’s health has continued to improve overall, in part because of the resources that have been devoted to health education, public health programs, health research, and health care. The United States spends more per capita than any other country on health care, and the rate of increase in spending is going up. Much of this spending is on health care that controls or reduces the impact of chronic diseases and conditions affecting an increasingly older population; notable examples are prescription drugs and cardiac operations. The older population also averaged more physician contacts than persons younger than 65: 11 contacts versus 5 contacts (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Persons who share the experience of a particular event or time in history are grouped together in what is called a cohort. They shared certain experiences at similar stages of physical, psychologic, and social development that influenced the way they perceive the world. Therefore they develop attitudes and values that are similar (Cox, 1986; Richardson, 1996). By understanding cohorts, the nurse develops a greater understanding of older adults’ value systems. For example, persons who reached maturity in the Depression learned the value of having a job and working hard to keep it. Generally, persons in this cohort have been loyal workers. They feel better if they are “doing their jobs.” The nurse might increase adherence with a treatment regimen by referring to the need for adherence as an older adult’s “job.” The age cohort that reached young adulthood in the post-World War II and Korean War era benefited from a very productive time in American history. The late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were times of rapidly increasing earnings and heavy spending. Strong unions negotiated for better pension plans and medical benefits. This cohort became accustomed to contacting professionals for services, thereby becoming more conscious of preventive health care than previous generations. This group has become aware of wellness techniques and self-care strategies that improve health. Members of this cohort usually have at least a high school education and often have some form of higher education. Many pursued further educational opportunities. As a group, however, they experience a less cohesive family life. Many have moved from their home communities and have experienced divorce, remarriage, or other circumstances that complicate family support (Johnson, 1992). The workforce was expanded to include more women, many of whom continued to work after the war. In 1940, 12 million women were working; by 1945, 19 million women were working (Wapner, Demick, & Redondo, 1990). Men and women serving in the armed forces became accustomed to regular physical and dental checkups, and they extended these practices to their families after the war. Veterans took advantage of the G.I. Bill to pursue a college education, which would have been unobtainable otherwise. With the help of veterans’ benefits, they purchased houses for little or no money down. Having experienced the trauma of war, this group developed an appetite for the good things in life and willingly paid for them. Many of today’s conveniences, including antibiotics, were not available during the 1930s. The technology now used in health care settings, ranging from electronic thermometers to computed tomography and positron emission tomography scanners, represents a true technologic explosion to persons who have witnessed its development. Today’s older adult cohort has survived many significant changes. Among those changes is the family living arrangement of the approximately 450,000 grandparents aged 65 or older that have primary responsibility for their grandchildren who live with them (Administration on Aging (AOA), 2009). Income and income sources for older adults differ according to age. Although income generally decreases with age, net worth peaks among householders ages 65 to 69. However, even though net worth decreases with advancing age, it remains substantial in older age groups. The median income of older adults in 2007 was $24,323 for men and $14,021 for women. Median money income (after adjusting for inflation) of all households headed by older adults did not change in a statistically different amount from 2006 to 2007. Households containing families headed by persons older than 65 reported a median income in 2007 of $41,851, according to “A Profile of Older Americans: 2008” (Administration on Aging, 2009). In 2006, Social Security was the primary income source for 89% of Americans older than 65. This federal government package of protection provides benefits for retired individuals, survivors of participants, and the disabled. Funds for Social Security are derived from payroll taxes, and benefits are earned by accumulating credits based on annual income. A person can earn up to four credits a year by working and paying Social Security taxes. In 2006 about 55% of older persons also reported income from other assets, and 29% of older adults reported private pensions. Government employee pensions were reported by 14%, and additional wages were reported by 25% of all older adults in this national survey by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, National Center on Health Statistics, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (AOA, 2009). Retirement age in the United States is not mandatory but is usually around age 65. A person can begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits as early as age 62. However, if a person begins receiving early benefits, monthly payments will be lower. Those born before 1938 are eligible for full Social Security benefits at age 65. However, beginning in 2003 the age at which full benefits are payable began increasing in gradual steps from 65 to 67 (Table 7–1). For those who wish to delay retirement, the benefit increases by a certain percentage depending on the year of birth. The yearly rate of increase varies from 3% for those born before 1924 to 8% for those born in 1943 or later (Retirement, 1997). TABLE 7–1 AGE TO RECEIVE FULL SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS From Social Security Online: Retirement age, Baltimore, 2009, US Department of Health and Human Services, Social Security Administration. Retrieved February 1, 2010, from http://www.ssa.gov/pubs/retirechart.htm Very poor older adults depend on another federal government program. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) pays monthly checks to persons who are aged, disabled, or sight impaired and who have few assets and minimal income. This program is also regulated by the Social Security Administration, but the money to provide benefits is from income tax sources rather than Social Security payroll taxes. Eligibility depends on income and assets. Additional information is obtainable through the government’s internet site www.socialsecurity.gov. Income sources for this age group are diverse. Most members of the group are still working; thus wage and salary earnings are substantial. Households often have two incomes because more women in this age group work. However, the number of men in this age group participating in the labor force has fallen dramatically since 1970. Those who are displaced from their jobs before the age of 60 experience a loss in earnings of 39%, and the rate of health insurance coverage is 16% lower than for those who are employed (Couch, 1998). With the downturn in employment hours, forced early retirement, or job loss experienced in the late 2000s, many older adults between ages 60 and 65 may or may not have pension plans. Savings and investments are used prematurely when an older adult loses employment. Financial losses taken in the mid- to late 2000s reduced hundreds of thousands of investment portfolios to minimal levels. For those older than 62, Social Security may provide part of their income. Interest and investment dividends contribute to income, but the income from these sources is usually insignificant. Retirement ordinarily causes income to decrease by about 35% or more. The median income before taxes for households ages 65 to 74 is $24,323, which is approximately $11,000 less than the median income of households in the 55 to 64 age bracket (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). This reduction in income is often offset by reduced expenditures associated with working, such as transportation, clothing, and meals. In this age group 19% of household heads continue to work. However, only half of those wage earners bring home more than $12,500 per year (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). The work is generally part time, so the portion of household income from wages and salary is reduced. Today this age group includes many veterans from World War II and the Korean War. Veterans’ benefits are important to this age group because of the increased risk of chronic disease and other acute health problems. Eligibility for veterans’ benefits is based on military service, service-related disability, and income. Benefits are considered on an individual basis (Federal benefits for veterans and dependents, 1993) (Box 7–1). Although benefits such as Medicare, food stamps, and housing assistance are not often thought of as income, they are factors used when assessing the poverty status of older adults in the United States. After age 75, women outnumber men in American society. Many persons in this age group live alone, which affects their average household income. Most women in this age group did not work outside the home, so their incomes depend on their spouses’ pensions or Social Security benefits. Surviving spouses with no work experience receive about two thirds of the overall income earned before the death of their spouses (Wapner, Demick, & Redondo, 1990). These findings have not been disputed in the 20 years since this study was published. Because few persons in this age group are employed and most who still work are self-employed, wages and salaries are a small income factor. Social Security is the most important factor. Pensions are available to fewer persons, and those who receive pensions receive less than younger age groups. Income from investments increases slightly (Wapner, Demick, & Redondo, 1990). This group is the fastest growing segment of our population (Table 7–2). Although the life span of Americans has been prolonged by medical and social advances, this age cohort is at risk for an increase in chronic disease, resulting in decreased ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and increased expenses for assistance, assistive devices, and medication (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005; Van Nostrand, Furner, & Suzman, 1993). TABLE 7–2 POPULATION 65 YEARS OR OLDER BY GENDER AND AGE GROUP: 1980 TO 2008 From US Census Bureau: The 2010 statistical abstract. Retrieved February 1, 2010, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/educ-attn.html. This group has the lowest average annual income level (less than $15,000) of all older Americans (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Social Security is the primary income source, although fewer members of this group are covered by Social Security. Pension and investment income is less than for younger groups, whereas SSI is increased. More members of this age group receive assistance from family, but the amount is small and often sporadic. Few receive wages or salary. The 85 or older group is more likely to need assistance with ADLs. They are also more likely to need institutional and home care (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005; Van Nostrand, Furner, & Suzman, 1993). Dependence on medication and assistive devices increases. If persons in this age group live independently, their housing is likely to be old and in need of repairs and maintenance (Mack et al, 1997). Adaptations to compensate for decreasing abilities help older adults remain in their homes, but these changes can be costly. Some older adults choose to move in with family or to facilities that offer assistance. In 1996 almost one fifth (18.4%) of those age 65 or older were classified as poor or near-poor, with income between the poverty level and 125% of this level (American Association of Retired Persons [AARP], 1997). One of every 11 older white adults (9.4%) are poor compared with one fourth (25.3%) of older black adults and one fourth (24.4%) of older Hispanic adults. The poverty rate for older women is 13.6%, whereas the rate for older men is 6.8%. Almost half (47.5%) of older black women who live alone are poor. The poverty rate is also high for those who live in metropolitan areas or the South, have not completed high school, or are too ill or disabled to work (AARP, 1997; US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Asians and other racial/ethnic groups were not included. Older black and Hispanic adults are more vulnerable to poverty than are whites. Many are more likely to have held low-paying jobs with few or no benefits. Black Americans older than 55 years are less educated as a group. Few reports of other racial/ethnic groups are available during this reporting time (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Educational attainment of older adults in general is identified in Table 7–3. The U.S. Census Bureau is planning an aggressive campaign to encourage all racial/ethnic groups to fully participate in the 2010 Census. This will allow all Americans access to government programs. TABLE 7–3 EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT OF OLDER ADULTS BY AGE: 2008 From US Census Bureau: The 2010 statistical abstract. Retrieved February 1, 2010, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/educ-attn.html. Low income may affect the quality of life for older adults. For example, basics such as housing and diet may be inadequate. An aging wardrobe and lack of transportation may cause the older adult to avoid social contact, leading to isolation. Older adults may delay seeking medical help or may not follow through with the prescribed treatment or medications because of limited income. Eyeglasses, hearing aids, and dental work may become unaffordable luxuries. Identifying an older client’s income level enables the nurse to direct the client to agencies and services that are available to those with limited resources (see Fig. 7–1A and Fig. 7–1B). Education has been shown to have a strong relationship to health risk factors (Brown, 1995). The level of education influences earning ability, information absorption, problem-solving ability, value systems, and lifestyle behaviors. The more educated person often has greater access to wellness programs and preventive health options (Land et al, 1994). The educational level of the older population has been steadily increasing, reflecting increased mandatory education and better educational opportunities in the last 50 years. The percentage of individuals who completed high school varies by race and ethnic origin. In 1995, 67% of older white adults had completed high school compared with 37% of black Americans and 30% of Hispanics (AARP, 1997; US Census Bureau, 1996). The educational level may be seen to rise even further after new data are gathered from the 2010 Census Report. Many older adults continue their education in their later years. From 1994 to 1995, 15% of those older than 65 participated in adult education courses (US Census Bureau, 1996). Some were completing high school or taking college courses. High school equivalency programs and reduced college tuition fostered this trend. Others took advantage of continuing education programs such as Elderhostel to explore subjects of interest. The Elderhostel program offers opportunities for persons older than 60 and their spouses to attend courses on specific topics, often held in 1-week segments on college campuses throughout the world. Low costs, made possible by volunteer professional instructors, on-campus housing, and other cost-saving factors, make the programs available to many. Erikson’s seventh stage of development stresses how important generativity versus stagnation is to the individual’s sense of achievement and fulfillment in life (Cox, 1986). Education provides an opportunity to avoid stagnation and isolation and adds to the enjoyment of later life. Teaching older adults with disabilities can be a challenge for nurses when the teaching is a part of health education. See Box 7–2 for suggestions related to the learning environment of those with memory, vision, or adherence issues. The health status of older adults influences their socioeconomic status. Persons older than 65 have an average of two chronic conditions (Lorig, 1993). The most common chronic problems in 2002 were arthritis (50%), followed by hypertension (36%), heart disease (32%), hearing impairments (29%), cataracts (17%), orthopedic impairments (16%), sinusitis (15%), and diabetes (10%) (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). The influence health problems exert often depends on the older person’s perception of the problem. Among noninstitutionalized persons, 74.3% of those ages 65 to 74 consider their health to be good, very good, or excellent compared with others their age, as do 66.8% of those 75 or older (US Census Bureau, 1996). Some approach health problems with an attitude of acceptance, whereas others find that chronic problems require considerable energy, and they spend extensive time and resources finding ways to cope or adapt (Burke & Flaherty, 1993). Functional status is affected by chronic conditions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports in Healthy Aging for Older Americans (2004) that functional status is important because it serves as an indicator of an older adult’s ability to remain independent in the community. Functional ability is measured by the individual’s ability to perform ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). ADLs include six personal care activities: eating, toileting, bathing, transferring, dressing, and continence. The term IADLs refers to the following home-management activities: preparing meals, shopping, managing money, using the telephone, doing light housework, doing laundry, using transportation, and taking medications appropriately. Data concerning the ability to perform ADLs and IADLs were gathered through the National Health Interview Survey. For more information on chronic conditions and their impact, see Chapter 17. Nurses can work with older adults to prolong independence by encouraging self-management of chronic conditions. Self-management is defined as learning and practicing the skills necessary to carry on an active and emotionally satisfying life in the face of a chronic condition (Lubkin & Larsen, 2002). Education and support help older adults make informed choices, practice good health behaviors, and take responsibility for the care of a chronic condition. A comprehensive service delivery system built on capitated benefits through Medicare and Medicaid funding is called the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE). The program is a state option under Medicare with additional funding from Medicaid; participants can receive services at home rather than be institutionalized. All services are delivered through an interdisciplinary team of health care and social services members. Full financial responsibility is assumed by the providers of care regardless of the duration of care, amount of services used, or the scope of services provided. Because no deductibles, coinsurance, or other cost-sharing is done, the older adult must be certified eligible for nursing home care, be older than 55, and receive both Medicare and Medicaid (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2006). Many older adults have automobiles that have reached maximum depreciation. These automobile owners may still be carrying full coverage when all they need is liability insurance. They may also be able to save money by investigating senior discounts, choosing higher deductibles, and comparing premiums from several companies. Completion of a defensive driving course such as the AARP Driver Safety Program (2005) may help older adults qualify for lower insurance rates. Health insurance is a necessity for older adults because medical problems—and therefore medical expenses—increase with age. As persons age, they visit the doctor more often (US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Older adults spend more time in the hospital—an average of 6.8 days—compared with the average of 4.5 days spent by those younger than 65 (AARP, 1997; US Census Bureau, 2004–2005). Part A, the hospital insurance, helps pay for inpatient hospital care and some follow-up care such as a skilled nursing facility, home health services, and hospice care. A person is eligible for Medicare Hospital Insurance if he or she is age 65 or older and (1) is eligible for any type of monthly Social Security benefit or railroad retirement system benefit or (2) is retired from or the spouse of a person who was employed in a Medicare-covered government position. It costs nothing for those who contributed to Medicare taxes while they were working. If the person is not eligible for premium-free Part A, then a monthly premium can be paid, as long as the person meets citizenship or residency requirements and is age 65 or older or disabled. The 2010 premium amount for people who buy Part A is $461 each month (Medicare & You, 2010). Part B, the medical insurance, helps pay for (Medicare & You, 2010) • Outpatient hospital services and home health visits • Vision services provided by a qualified optometrist (excluding the cost of glasses) • Inpatient treatment of mental illness • Diagnostic x-ray, laboratory, and other tests • Surgical dressings, splints, and casts • Necessary ambulance services • Rental or purchase of durable medical equipment used in the home • Braces for limbs, back, or neck

Socioeconomic and Environmental Influences

Socioeconomic Factors

Age Cohorts

Income Sources

YEAR OF BIRTH

FULL RETIREMENT AGE

1937 or earlier

65

1938

65 and 2 months

1939

65 and 4 months

1940

65 and 6 months

1941

65 and 8 months

1942

65 and 10 months

1943–1954

66

1955

66 and 2 months

1956

66 and 4 months

1957

66 and 6 months

1958

66 and 8 months

1959

66 and 10 months

1960 or later

67

Ages 55 to 64

Ages 65 to 74

Ages 75 to 84

Ages 85 and Older

GENDER AND AGE GROUP

PERCENT DISTRIBUTION

2008

1980

1990

2000

All Persons

65 years and older

100

100

100

100

65 to 74 years old

61

58

53

52

75 to 84 years old

30

32

35

34

85 years and older

9

10

12

15

Men

65 years and older

100

100

100

100

65 to 74 years old

66

63

58

56

75 to 84 years old

28

30

34

32

85 years and older

7

7

9

11

Women

65 years and older

100

100

100

100

65 to 74 years old

59

55

49

48

75 to 84 years old

32

34

36

34

85 years and older

10

12

15

17

Poverty

AGE

HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATE

PERCENTAGE OF POPULATION—HIGHEST LEVEL

ASSOCIATE’S DEGREE

BACHELOR’S DEGREE

ADVANCED DEGREE

55 to 64 years old

30.7

8.9

18.3

12.8

65 to 74 years old

35.7

6.0

13.4

10.0

75 years and older

38.1

4.1

10.3

6.7

Education

Health Status

Insurance Coverage

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Socioeconomic and Environmental Influences

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access