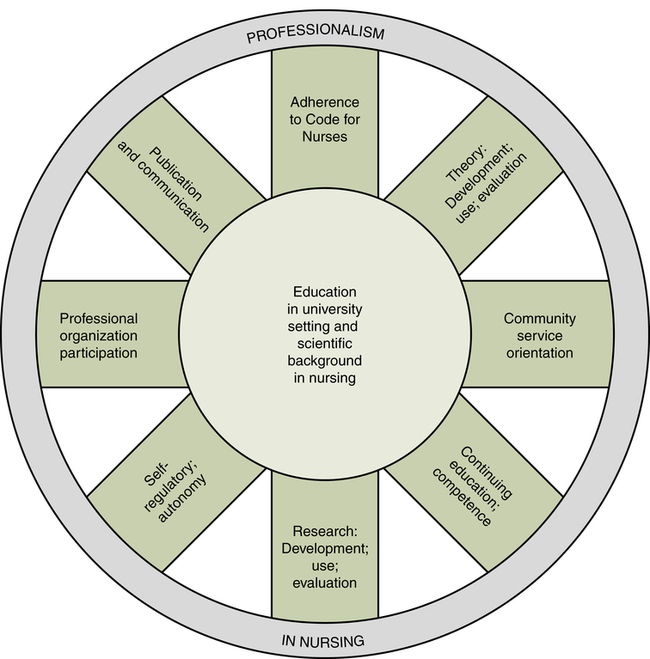

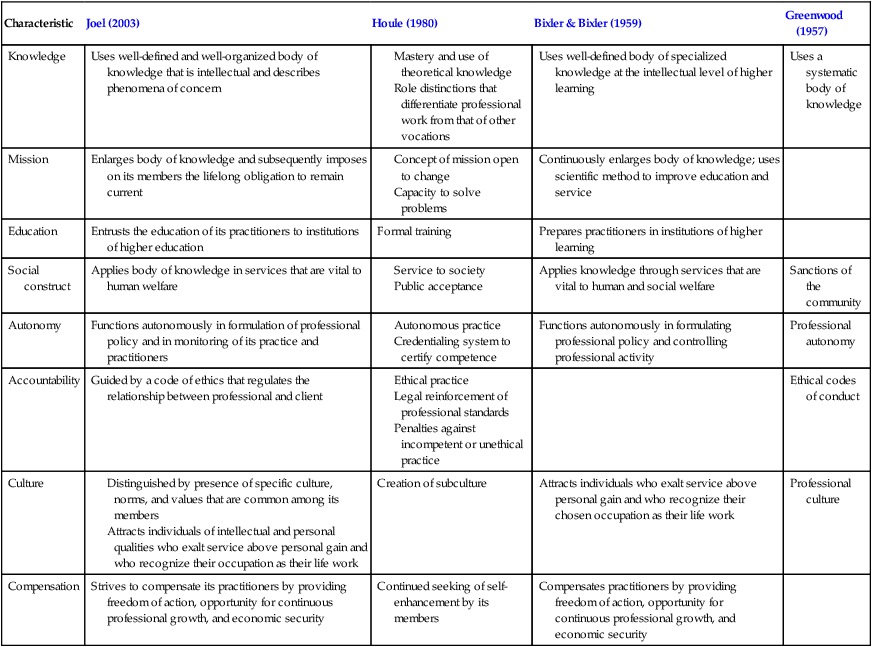

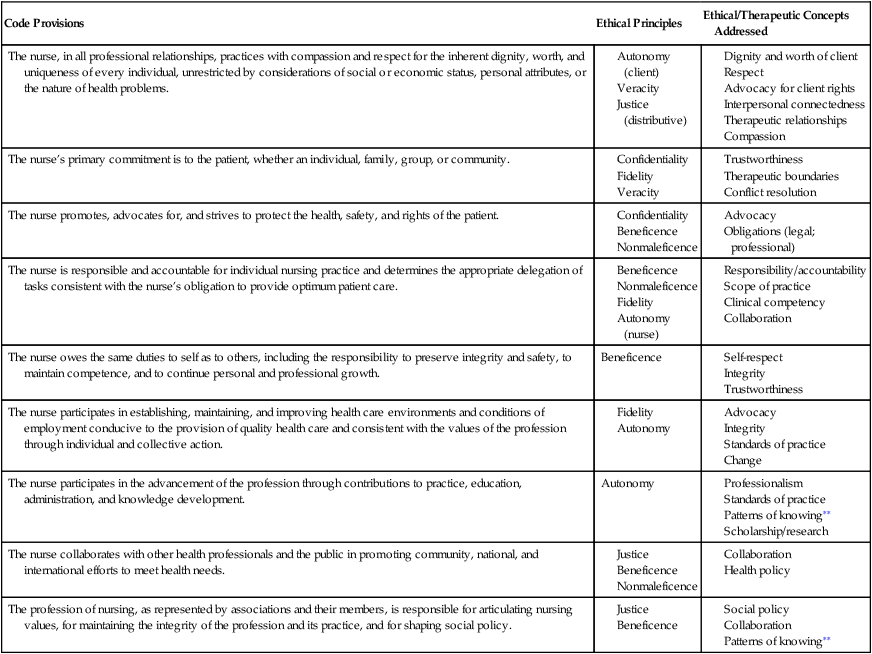

Karen J. Saewert, PhD, RN, CPHQ, CNE At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Evaluate the current status of nursing as a profession. • Describe the barriers that slow the professionalization of nursing. • Discuss factors that influence professional socialization. • Differentiate accountability, autonomy, and shared governance as characteristics of professional practice. • Describe the relationship between professional socialization and participation in professional nursing associations. The roots of nursing are firmly anchored in service to others: individuals, groups, and communities. Since the days of Florence Nightingale, nurses have entered nursing to help people and serve the health care needs of society. This service orientation is evident in the Nightingale Pledge, which has been spoken by millions of nurses since the late 1800s. Dedication to duty is reflective of nursing’s evolutionary links from holy orders (Birchenall, 1998). The pledge concludes with “devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care” (American Nurses Association. Nursing World: Media resources, n.d.). But are devotion and caring sufficient for nursing to call itself a profession? This question has stimulated discussion, debate, and controversy within health care and related disciplines. The ongoing debate about what nursing is and is not is timely and essential as the profession delineates its place within the emerging new order of health care delivery (Gordon, 2005). In response to concerns about the quality of educational programs in medical schools, particularly admission standards and curriculum, the Carnegie Foundation issued a series of papers. Abraham Flexner’s classic paper (1910) was part of this series and served as the catalyst for reform of medical education in the United States and Canada. Flexner’s recommendations were supported by the American Medical Association and the American Public Health Association. Their collective efforts, along with the willingness of members of the medical community to embrace a major reorientation of medical education, led to changing the face of medicine within a 10-year period, strengthened medicine as a profession, and raised its status in the eyes of the public (Schwirian, 1998). • It is basically intellectual (as opposed to physical), with high responsibility. • It is based on a body of knowledge that can be learned. • It is practical (applied) rather than theoretical. • It can be taught through the process of professional education. • It has a strong internal organization of members. • It has practitioners who are motivated by altruism (the desire to help others). Since Flexner’s work in 1915, additional authors have modified and amplified the criteria of a profession. The works of Greenwood (1957), Bixler and Bixler (1959), Houle (1980), and Joel (2003) are summarized in Table 3-1. The cluster of characteristics that emerges include (1) relevance to social values and needs, (2) a lengthy and required education, (3) a code of ethics, (4) a mechanism for self-regulation, (5) research-based theoretical frameworks for practice, (6) common identity and distinctive subculture, and (7) members motivated by altruism and commitment to the profession. TABLE 3-1 Characteristics of a Profession A specified body of knowledge and altruism are the most widely acknowledged characteristics of a profession. A professional possesses unique knowledge, and members of the profession acquire this knowledge through a significant period of training. Group members profess to be knowledgeable in an area that is not known by most people but which society needs. Members also are invested with a service ideal, altruism. Nursing actions convince the public that members are not self-serving but use knowledge to benefit the public. Society then grants autonomy or control to the profession to set its standards and regulate practice (McCloskey & Maas, 1998). What society sees as nursing has, to a large extent, influenced nursing’s public image: “The manner in which the public thinks of nurses will strongly influence the destiny of nursing and the contributions that nurses can make to better health care” (Kalisch & Kalisch, 2005, p. 16). Members of the public play an important role as they are called on to participate in decision-making processes in health care by voting, organizing, and exercising influence on government. For public citizens to do this responsibly and to make intelligent judgments, they need a clear awareness of nursing activities; however, the public more typically holds an “obsolete, one-dimensional image of nurses and their roles” (Kalisch & Kalisch, 2005, p. 16). Benner (2005), in a commentary to the Kalisch and Kalisch article, indicates that “nurses’ voices are still relatively silent in the newspapers” (p. 14). She continues saying that nurses do much but say little in public arenas. However, outsiders cannot be expected to be the major champions of the visibility of nursing; nurses must move from “silence to voice” through public communication about nurses and nursing (Buresch & Gordon, 2000). Professionalization is the process through which an occupation achieves professional status. The status of nursing as a profession is important because it reflects the value society places on the work of nurses and the centrality of this work to the good of society (Strader & Decker, 1995). Guided by the descriptions of what constitutes a profession, how does nursing measure up? At the time those criteria were being developed, nursing fell short of professional status in a number of areas. For example, most nursing education programs were based in hospitals and reflected an apprenticeship model rather than being in institutions of higher education. Nursing research was in its infancy, thereby offering little toward the identification of a unique body of knowledge that would improve nursing practice and education. In addition, autonomous nursing practice was relatively uncommon, and no formalized code of ethics existed. An analysis of nursing’s placement along the occupation-profession continuum reveals strengths and challenges. Strengths include (1) a service-to-society mission, (2) the provision of services that are vital to human welfare, and (3) a well-defined code of ethics. Challenges include (1) limited development of nursing theory and a unique body of nursing knowledge, (2) lack of standardization of nursing education, with university preparation still not the minimum entry requirement, (3) variation in members’ commitment to their work, and (4) minimal cohesive culture within the nursing community (Schwirian, 1998). Autonomy, the freedom to act, is a key characteristic present in all definitions of a profession and is clearly linked to achieving professional status. But autonomy is linked to other characteristics as well. A limited body of scientific knowledge and an incomplete articulation of phenomena unique to nursing are cited as major contributors to the lack of autonomy in nursing practice. Nursing is still viewed by many as a lower level of medical knowledge that should be under the jurisdiction of medicine (Wurst, 1994). In contrast, Gordon (2005) compares the difference between nurses and physicians to that of a ship’s captain and its pilot. She identifies similarities between a physician and the captain, suggesting that their knowledge is more abstract, with general skills needed to manage a vessel in open waters. In contrast, the nurse is similar to the ship’s pilot, possessing more particular knowledge that is highly contextual. She describes nurses as piloting patients into ports of health, coping, cure, and death. The development of nursing knowledge is fundamental to the professionalization of nursing. The science of nursing is concerned with developing a unified body of knowledge that includes skills and methods for applying that knowledge (Chinn & Kramer, 1999). Until the 1980s knowledge, by definition, was empirically based, focusing exclusively on objective, observable data and an analytical, linear line of reasoning. Since that time awareness has been growing that exclusive reliance on empirical data provides only a partial view of the world and that knowledge can best be expanded by using multiple approaches to scientific inquiry. Carper’s classic publication (1978) describes four fundamental and enduring patterns of knowing: According to Chinn and Kramer (1999), “the fundamental patterns of knowing remain valuable in that they conceptualize a broad scope of knowing that accounts for a holistic practice” (p. 4). Thus nursing knowledge is derived from theoretical formulations and scientific research, as well as an analysis of personal experiences that contributes to clinical knowledge and expertise. The continued development of a distinct body of knowledge will aid in differentiating nursing from other health professions and provide a stronger basis for practice. Other factors identified as limiting nursing’s autonomy include gender stereotypes and public image. Historically, women have been socialized to shy away from power and assume more subservient roles. Gordon (2005) cites the fusion of nursing and moral virtues as one of the building blocks of this 19th-century secularization and professionalization of nursing. If nursing is viewed as a calling, a form of penance, or a hobby, then education and experience will not seem relevant. The typical emphasis on the emotional aspects of nursing rather than on the required intelligence and skill returns attention to nurses as self-sacrificing and silent. Unfortunately, some of the current language being used in public relations efforts keeps nursing in this emotional state. Use of phrases such as “the noble profession,” “lifting spirits, touching lives,” or identifying rewards of nursing as being “big doses of public affection” and “a job where people will love you” returns nursing to that 19th-century stereotype. In sharp contrast, nursing is a profession with a high level of specificity. Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, and Sochalski (2001) describe nurses as the early warning and intervention systems; Gordon (2005) views nursing as creating order out of chaos and protecting patients from risk without making them feel at risk. Presentation of self may also act as a barrier to advancing the professional status of nursing. For example, “nurses’ verbal informality with patients is linked to persistent stereotypic themes that diminish the professional image, shroud the cognitive nature of their work, perpetuate hierarchical relationships between physicians and nurses, and even threaten nurses’ therapeutic effectiveness” (Campbell-Heider, Hart, & Bergren, 1994, pp. 212-213). However, attempts to elevate the language of nurses must be balanced with clarity in meaning. Gordon (2005) points to the confusion by the official-sounding statements used in nursing diagnoses. Use of this language is “an understandable attempt to give status to nursing work but ends up concealing it from those who have a need to know” (p. 217). She goes on to say that speaking English rather than “code” would help everyone better understand what nurses do. Gordon asserts that it would be far “more productive if nurses professionalized their appearance rather than their jargon” (p. 438). Indeed, clothing styles seem to diminish the professional status of nursing. The current style of dress may make nurses seem more accessible, but Gordon (2005) asserts that today’s common attire also makes nurses more forgettable, stating that the “new uniforms” make nurses look immature and silly, signaling that they are not a threat to anyone’s power or authority. In contrast, physicians continue to dress for status as well as easy identification. Nurses today tend to dress in “pajama-like outfits with heart, flower, and angel designs or in pastels. Nurses blend into an undifferentiated mass of people whose outfits signal an asymmetrical power relationship” (Gordon, 2005, p. 34), whereas most physicians wear lab coats or business suits. In response to an editorial on appropriate nursing attire in NurseWeek (Ulrich, 2005), comments from patients focused on the importance of being able to tell who the nurses are; they were less interested in color of uniform. In this article a nurse reader commented, “If nurses cannot agree on what image they present to their clients and the public, then how can nurses come together concerning nursing as a profession?” (p. 3). Takase, Kershaw, and Burt (2002) focused on nurses’ perceptions of common public stereotypes and identified that these perceptions were related to the development of self-concept, collective self-esteem, and job satisfaction. To counter these public stereotypes, nurses must be less modest about taking credit for what they know and do. Too often, nurses do not take ownership, but instead assign the credit to others. Other groups that attempt to control nursing, such as organized medicine and health services administration, are well organized, have clearly defined their unique content and roles, and are viewed as having control of professions that enjoy high status. However, the occupation-profession distinction is largely artificial. The designation of what is professional versus what is occupational is based on tradition and existing mechanisms (unions and academic departments) in an effort to maintain the status quo (McCloskey & Maas, 1998). Taking a different approach to professionalization, Adams, Miller, and Beck (1996) focus on the individual nurse. Their approach reflects the view of Styles (1982), who maintained that the individual and her or his personal presentation fosters the collective image of nursing. Citing lack of consensus among nurses on what behaviors exemplify professional status, Miller (1985) and Miller, Adams, and Beck (1993) drew from common definitions of a profession and added behaviors expressed in key nursing documents, such as early versions of the American Nurses Association’s Social Policy Statement and Code of Ethics for Nurses. Miller’s “wheel of professionalism” is presented in Figure 3-1. The basic education of a professional, occurring in a university setting with emphasis on the scientific basis of nursing, is at the hub of the wheel. The eight spokes extending from the hub represent behaviors deemed essential to achieving, maintaining, and expanding professionalism in the individual nurse. Florence Nightingale (1860), in her clear and direct manner, stated that the goal of nursing is to “put the patient in the best condition for nature to act upon him” (p. 133). This essence of nursing practice continues to be reflected in contemporary nursing. In the revised Social Policy Statement developed by the ANA (2003), six essential features of contemporary nursing practice are identified (p. 5): 1. Provision of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing 2. Attention to the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness within the physical and social environments 3. Integration of objective data with knowledge gained from an appreciation of the patient’s or group’s subjective experience 4. Application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment through the use of judgment and critical thinking 5. Advancement of professional nursing knowledge through scholarly inquiry 6. Influence on social and public policy to promote social justice Knowledge, skills, and ethical grounding of the nurse directly affect the quality of care provided. The profession’s values give direction and meaning to its members, guide nursing behaviors, are instrumental in clinical decision making, and influence how nurses think about themselves. Although skills change and evolve over time, core values of nursing persist and are communicated through the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses (ANA, 2001). With licensure as a registered nurse, each nurse accepts responsibility for practicing nursing consistent with these values. The Code of Ethics for Nurses with associated ethical principles is summarized in Table 3-2 and discussed further in the chapter on ethics (Chapter 12). Note that philosophical ethical principles and concepts of interpersonal relationships are reflected, either directly or indirectly, in all the canons. The ethical principles are those most directly reflected in the respective canons. TABLE 3-2 ∗Based on the American Nurses Association. (2001). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretative statements. Washington, DC: Author. ∗∗Carper, B. A. (1978). Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. Advances in Nursing Science, 1(1), 13-23. Courtesy B. P. Fargotstein, Tempe, AZ. Weis and Schank (2000) developed and tested an instrument based on the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses that measured professional nursing values. Included were 44 short descriptive phrases (each reflecting a specific code statement), along with interpretive commentary for each phrase. With a sample of 599 respondents, caregiving was the predominant professional nursing value identified. Examining professional values held by baccalaureate and associate degree nursing students, Martin, Yarbrough, and Alfred (2003) found that the student groups did not differ significantly. However, significant differences were found for both gender and ethnicity. Men scored lower on all subscales and on the total scale. Ethnic groups differed on responses to three subscales representing respect for human dignity, safeguarding the client and public, and collaborating to meet public health needs. Service to society has remained a central value of nursing, and nursing’s consistent provision of service to benefit the public has earned the public’s trust. A key component in preserving this trust is accountability. Accountability is the state of being responsible and answerable for one’s own behavior. This is explicit in the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001): “Nurses are accountable for judgements made and actions taken in the course of nursing practice irrespective of health care organizations’ policies or providers’ directives” (p. 16). Accountability extends to self, the client, the employing agency, the profession, and the public. The ANA’s Scope and Standards of Clinical Nursing Practice (2004) describe both the “what” and “how” of professional nursing. Standards of practice are the “what” and describe a competent level of nursing care through use of the nursing process. Standards of professional performance are the “how” of nursing, with nine standards describing a competent level of behavior in the professional role. Each standard is accompanied by criteria that permit measurement of performance and characterize competent, professional practice. These standards are listed in Box 3-1. Further elaboration of professional nursing responsibilities can be found in the standards of care for the various specialty practices.

Socialization to Professional Nursing

![]() Nursing as a Profession

Nursing as a Profession

CHARACTERISTICS OF A PROFESSION

Characteristic

Joel (2003)

Houle (1980)

Bixler & Bixler (1959)

Greenwood (1957)

Knowledge

Uses well-defined and well-organized body of knowledge that is intellectual and describes phenomena of concern

Uses well-defined body of specialized knowledge at the intellectual level of higher learning

Uses a systematic body of knowledge

Mission

Enlarges body of knowledge and subsequently imposes on its members the lifelong obligation to remain current

Continuously enlarges body of knowledge; uses scientific method to improve education and service

Education

Entrusts the education of its practitioners to institutions of higher education

Formal training

Prepares practitioners in institutions of higher learning

Social construct

Applies body of knowledge in services that are vital to human welfare

Applies knowledge through services that are vital to human and social welfare

Sanctions of the community

Autonomy

Functions autonomously in formulation of professional policy and in monitoring of its practice and practitioners

Functions autonomously in formulating professional policy and controlling professional activity

Professional autonomy

Accountability

Guided by a code of ethics that regulates the relationship between professional and client

Ethical codes of conduct

Culture

Creation of subculture

Attracts individuals who exalt service above personal gain and who recognize their chosen occupation as their life work

Professional culture

Compensation

Strives to compensate its practitioners by providing freedom of action, opportunity for continuous professional growth, and economic security

Continued seeking of self-enhancement by its members

Compensates practitioners by providing freedom of action, opportunity for continuous professional growth, and economic security

![]() Professionalization of Nursing

Professionalization of Nursing

BARRIERS TO PROFESSIONALISM

A MODEL FOR PROFESSIONALISM

![]() Professional Nursing Practice

Professional Nursing Practice

VALUES OF THE PROFESSION

Code Provisions

Ethical Principles

Ethical/Therapeutic Concepts Addressed

The nurse, in all professional relationships, practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual, unrestricted by considerations of social or economic status, personal attributes, or the nature of health problems.

The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, or community.

The nurse promotes, advocates for, and strives to protect the health, safety, and rights of the patient.

The nurse is responsible and accountable for individual nursing practice and determines the appropriate delegation of tasks consistent with the nurse’s obligation to provide optimum patient care.

The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to preserve integrity and safety, to maintain competence, and to continue personal and professional growth.

Beneficence

The nurse participates in establishing, maintaining, and improving health care environments and conditions of employment conducive to the provision of quality health care and consistent with the values of the profession through individual and collective action.

The nurse participates in the advancement of the profession through contributions to practice, education, administration, and knowledge development.

Autonomy

The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public in promoting community, national, and international efforts to meet health needs.

The profession of nursing, as represented by associations and their members, is responsible for articulating nursing values, for maintaining the integrity of the profession and its practice, and for shaping social policy.

Socialization to Professional Nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access