Sleep

Objectives

• Explain the effect that the 24-hour sleep-wake cycle has on biological function.

• Discuss mechanisms that regulate sleep.

• Describe the stages of a normal sleep cycle.

• Explain the functions of sleep.

• Compare and contrast the sleep requirements of different age-groups.

• Identify factors that normally promote and disrupt sleep.

• Discuss characteristics of common sleep disorders.

• Conduct a sleep history for a patient.

• Identify nursing diagnoses appropriate for patients with sleep alterations.

• Identify nursing interventions designed to promote normal sleep cycles for patients of all ages.

Key Terms

Biological clocks, p. 940

Cataplexy, p. 944

Circadian rhythm, p. 939

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), p. 943

Hypersomnolence, p. 942

Hypnotics, p. 957

Insomnia, p. 942

Narcolepsy, p. 944

Nocturia, p. 942

Nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, p. 940

Polysomnogram, p. 942

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, p. 940

Rest, p. 944

Sedatives, p. 957

Sleep, p. 939

Sleep apnea, p. 943

Sleep deprivation, p. 944

Sleep hygiene, p. 942

![]()

Proper rest and sleep are as important to health as good nutrition and adequate exercise. Physical and emotional health depends on the ability to fulfill these basic human needs. Individuals need different amounts of sleep and rest. Without proper amounts, the ability to concentrate, make judgments, and participate in daily activities decreases; and irritability increases.

Identifying and treating patients’ sleep pattern disturbances are important goals. To help patients you need to understand the nature of sleep, the factors influencing it, and patients’ sleep habits. Patients require individualized approaches based on their personal habits, patterns of sleep, and the particular problem influencing sleep. Nursing interventions are often effective in resolving short- and long-term sleep disturbances.

Sleep provides healing and restoration (McCance et al., 2010). Achieving the best possible sleep quality is important for the promotion of good health and recovery from illness. Ill patients often require more sleep and rest than healthy patients. However, the nature of illness often prevents some patients from getting adequate rest and sleep. The environment of a hospital or long-term care facility and the activities of health care personnel make sleep difficult. Some patients have preexisting sleep disturbances; other patients develop sleep problems as a result of illness or hospitalization.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Physiology of Sleep

Sleep is a cyclical physiological process that alternates with longer periods of wakefulness. The sleep-wake cycle influences and regulates physiological function and behavioral responses.

Circadian Rhythms

People experience cyclical rhythms as part of their everyday lives. The most familiar rhythm is the 24-hour, day-night cycle known as the diurnal or circadian rhythm (derived from Latin: circa, “about,” and dies, “day”). The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) nerve cells in the hypothalamus control the rhythm of the sleep-wake cycle and coordinate this cycle with other circadian rhythms (McCance et al., 2010). Circadian rhythms influence the pattern of major biological and behavioral functions. The predictable changing of body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, hormone secretion, sensory acuity, and mood depend on the maintenance of the 24-hour circadian cycle (Van der Zee et al., 2009).

Factors such as light, temperature, social activities, and work routines affect circadian rhythms and daily sleep-wake cycles. All persons have biological clocks that synchronize their sleep cycles. This explains why some people fall asleep at 8 PM, whereas others go to bed at midnight or early in the morning. Different people also function best at different times of the day.

Hospitals or extended care facilities usually do not adapt care to an individual’s sleep-wake cycle preferences. Typical hospital routines interrupt sleep or prevent patients from falling asleep at their usual time. Poor quality of sleep results when a person’s sleep-wake cycle changes. Reversals in the sleep-wake cycle, such as when a person who is normally awake during the day falls asleep during the day, often indicate a serious illness.

The biological rhythm of sleep frequently becomes synchronized with other body functions. For example, changes in body temperature correlate with sleep patterns. Normally body temperature peaks in the afternoon, decreases gradually, and then drops sharply after a person falls asleep. When the sleep-wake cycle becomes disrupted (e.g., by working rotating shifts), other physiological functions usually change as well. For example, a new nurse who starts working the night shift experiences a decreased appetite and loses weight. Anxiety, restlessness, irritability, and impaired judgment are other common symptoms of sleep cycle disturbances. Failure to maintain an individual’s usual sleep-wake cycle negatively influences the patient’s overall health.

Sleep Regulation

Sleep involves a sequence of physiological states maintained by highly integrated central nervous system (CNS) activity. It is associated with changes in the peripheral nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, and muscular systems (McCance et al., 2010). Specific physiological responses and patterns of brain activity identify each sequence. Instruments such as the electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the cerebral cortex; the electromyogram (EMG), which measures muscle tone; and the electrooculogram (EOG), which measures eye movements provide information about some structural physiological aspects of sleep.

The major sleep center in the body is the hypothalamus. It secretes hypocreatins (orexins) that promote wakefulness and rapid eye movement sleep. Prostaglandin D2, L-tryptophan, and growth factors control sleep (McCance et al., 2010).

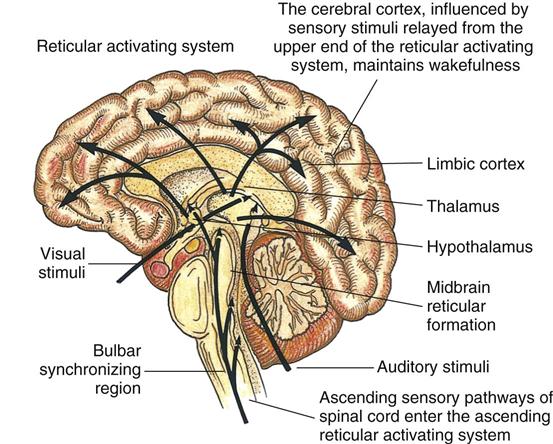

Researchers believe that the ascending reticular activating system (RAS) located in the upper brainstem contains special cells that maintain alertness and wakefulness. The RAS receives visual, auditory, pain, and tactile sensory stimuli. Activity from the cerebral cortex (e.g., emotions or thought processes) also stimulates the RAS. Arousal, wakefulness, and maintenance of consciousness result from neurons in the RAS releasing catecholamines such as norepinephrine (Izac, 2006).

Researchers hypothesize that the release of serotonin from specialized cells in the raphe nuclei sleep system of the pons and medulla produces sleep. This area of the brain is also called the bulbar synchronizing region (BSR). Whether a person remains awake or falls asleep depends on a balance of impulses received from higher centers (e.g., thoughts), peripheral sensory receptors (e.g., sound or light stimuli), and the limbic system (emotions) (Fig. 42-1). As people try to fall asleep, they close their eyes and assume relaxed positions. Stimuli to the RAS decline. If the room is dark and quiet, activation of the RAS further declines. At some point the BSR takes over, causing sleep.

Stages of Sleep

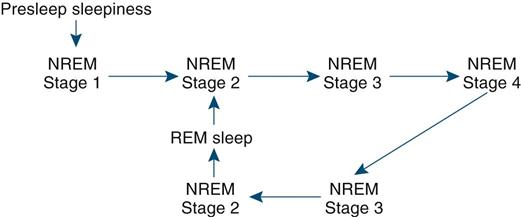

Current theory suggests that sleep is an active multiphase process. Different brain-wave, muscle, and eye activity is associated with different stages of sleep (Izac, 2006). Normal sleep involves two phases: nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Box 42-1). During NREM a sleeper progresses through four stages during a typical 90-minute sleep cycle. The quality of sleep from stage 1 through stage 4 becomes increasingly deep. Lighter sleep is characteristic of stages 1 and 2, during which a person is more easily aroused. Stages 3 and 4 involve a deeper sleep, called slow-wave sleep. REM sleep is the phase at the end of each sleep cycle. Different factors promote or interfere with various stages of the sleep cycle.

Sleep Cycle

The normal sleep pattern for an adult begins with a presleep period during which the person is aware only of a gradually developing sleepiness. This period normally lasts 10 to 30 minutes; however, if a person has difficulty falling asleep, it lasts an hour or more.

Once asleep, the person usually passes through four or five complete sleep cycles per night, each consisting of four stages of NREM sleep and a period of REM sleep (McCance et al., 2010). Each cycle lasts approximately 90 to 100 minutes. The cyclical pattern usually progresses from stage 1 through stage 4 of NREM, followed by a reversal from stages 4 to 3 to 2, ending with a period of REM sleep (Fig. 42-2). A person usually reaches REM sleep about 90 minutes into the sleep cycle. Seventy-five to eighty percent of sleep time is spent in NREM sleep.

With each successive cycle stages 3 and 4 shorten, and the period of REM lengthens. REM sleep lasts up to 60 minutes during the last sleep cycle. Not all people progress consistently through the stages of sleep. For example, a sleeper moves back and forth for short intervals between NREM stages 2, 3, and 4 before entering REM stage. The amount of time spent in each stage varies over the life span. Newborns and children spend more time in deep sleep. Sleep becomes more fragmented with aging, and a person spends more time in lighter stages (National Sleep Foundation, 2009). Shifts from stage to stage of sleep tend to accompany body movements. Shifts to light sleep or wakefulness tend to occur suddenly, whereas shifts to deep sleep tend to be gradual (Izac, 2006). The number of sleep cycles depends on the total amount of time that the person spends sleeping.

Functions of Sleep

The purpose of sleep remains unclear. It contributes to physiological and psychological restoration. NREM sleep contributes to body tissue restoration (McCance et al., 2010). During NREM sleep biological functions slow. A healthy adult’s normal heart rate throughout the day averages 70 to 80 beats/min or less if the individual is in excellent physical condition. However, during sleep the heart rate falls to 60 beats/min or less, which benefits cardiac function. Other biological functions decreased during sleep are respirations, blood pressure, and muscle tone (McCance et al., 2010).

The body needs sleep to routinely restore biological processes. During deep slow-wave (NREM stage 4) sleep, the body releases human growth hormone for the repair and renewal of epithelial and specialized cells such as brain cells (McCance et al., 2010). Protein synthesis and cell division for renewal of tissues such as the skin, bone marrow, gastric mucosa, or brain occur during rest and sleep. NREM sleep is especially important in children, who experience more stage 4 sleep.

Another theory about the purpose of sleep is that the body conserves energy during sleep. The skeletal muscles relax progressively, and the absence of muscular contraction preserves chemical energy for cellular processes. Lowering of the basal metabolic rate further conserves body energy supply (Izac, 2006).

REM sleep is necessary for brain tissue restoration and appears to be important for cognitive restoration. It is associated with changes in cerebral blood flow, increased cortical activity, increased oxygen consumption, and epinephrine release. This association assists with memory storage and learning (McCance et al., 2010).

The benefits of sleep on behavior often go unnoticed until a person develops a problem resulting from sleep deprivation. A loss of REM sleep leads to feelings of confusion and suspicion. Various body functions (e.g., mood, motor performance, memory, and equilibrium) are altered when prolonged sleep loss occurs (National Sleep Foundation, 2010a). Changes in the natural and cellular immune function also occur with moderate-to-severe sleep deprivation. Traffic, home, and work-related accidents caused by falling asleep cost billions of dollars a year in the United States because of lost productivity, health care costs, and accidents (Irwin et al., 2006).

Dreams

Although dreams occur during both NREM and REM sleep, the dreams of REM sleep are more vivid and elaborate; and some believe that they are functionally important to learning, memory processing, and adaptation to stress (Kryger et al., 2011). REM dreams progress in content throughout the night from dreams about current events to emotional dreams of childhood or the past. Personality influences the quality of dreams (e.g., a creative person has elaborate and complex dreams, whereas a depressed person dreams of helplessness).

Most people dream about immediate concerns such as an argument with a spouse or worries over work. Sometimes a person is unaware of fears represented in bizarre dreams. Clinical psychologists try to analyze the symbolic nature of dreams as part of a patient’s psychotherapy. The ability to describe a dream and interpret its significance sometimes helps resolve personal concerns or fears.

Another theory suggests that dreams erase certain fantasies or nonsensical memories. Because most people forget their dreams, few have dream recall or do not believe they dream at all. To remember a dream, a person has to consciously think about it on awakening. People who recall dreams vividly usually awake just after a period of REM sleep.

Physical Illness

Any illness that causes pain, physical discomfort, or mood problems such as anxiety or depression often results in sleep problems. People with such alterations frequently have trouble falling or staying asleep. Illnesses also force patients to sleep in unfamiliar positions. For example, it is difficult for a patient with an arm or leg in traction to rest comfortably.

Respiratory disease often interferes with sleep. Patients with chronic lung disease such as emphysema are short of breath and frequently cannot sleep without two or three pillows to raise their heads. Asthma, bronchitis, and allergic rhinitis alter the rhythm of breathing and disturb sleep. A person with a common cold has nasal congestion, sinus drainage, and a sore throat, which impair breathing and the ability to relax.

Connections between heart disease, sleep, and sleep disorders exist (Redeker, 2008). Sleep-related breathing disorders are linked to increased incidence of nocturnal angina (chest pain), increased heart rate, electrocardiogram changes, high blood pressure, and risk of heart diseases and stroke (McCance et al., 2010). Hypertension often causes early-morning awakening and fatigue. Hypothyroidism decreases stage 4 sleep, whereas hyperthyroidism causes persons to take more time to fall asleep. Research also identifies an increased risk of sudden cardiac death in the first hours after awakening.

Nocturia, or urination during the night, disrupts sleep and the sleep cycle. After repeated awakenings to urinate, returning to sleep is difficult, and the sleep cycle is not complete. This condition is most common in older people with reduced bladder tone or people with cardiac disease, diabetes, urethritis, or prostatic disease.

Many people experience restless legs syndrome (RLS), which occurs before sleep onset. More common in women, older people, and those with iron deficiency anemia, RLS symptoms include recurrent, rhythmical movements of the feet and legs. Patients feel an itching sensation deep in the muscles. Relief comes only from moving the legs, which prevents relaxation and subsequent sleep. RLS is sometimes a relatively benign condition, depending on how severely sleep is disrupted. Primary RLS is a CNS disorder. Researchers associate secondary RLS with lower levels of iron, pregnancy, and renal failure (Natarajan, 2010).

People with peptic ulcer disease often awaken in the middle of the night. Studies showing a relationship between gastric acid secretion and stages of sleep are conflicting. One consistent finding is that people with duodenal ulcers fail to suppress acid secretion in the first 2 hours of sleep (Kryger et al., 2011).

Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders are conditions that, if untreated, generally cause disturbed nighttime sleep that results in one of three problems: insomnia, abnormal movements or sensation during sleep or when awakening at night, or excessive daytime sleepiness (Kryger et al., 2011). Many adults in the United States have significant sleep problems from inadequacies in either the quantity or quality of their nighttime sleep and experience hypersomnolence on a daily basis (National Sleep Foundation, 2010a). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine developed the International Classification of Sleep Disorders version 2 (ICSD-2), which classifies sleep disorders into eight major categories (Box 42-2).

The insomnias are disorders related to difficulty falling asleep. Individuals with sleep-related breathing disorders have disordered respirations during sleep. Hypersomnia not caused by sleep-related breathing disorders is a group of disorders that is not caused by disturbed circadian rhythms or nocturnal sleep. The circadian rhythm sleep disorders are caused by a misalignment between the timing of sleep and individual desires or the societal norm. The parasomnias are undesirable behaviors that occur usually during sleep. Sleep and wake disturbances are associated with many medical and psychiatric sleep disorders, including psychiatric, neurological, or other medical disorders. In sleep-related movement disorders the person experiences simple stereotyped movements that disturb sleep. The category of isolated symptoms, apparently normal variants, and unresolved issues includes sleep-related symptoms that fall between normal and abnormal sleep. The other sleep disorders category contains sleep problems that do not fit into other categories.

Sleep laboratory studies diagnose a sleep disorder. A polysomnogram involves the use of EEG, EMG, and EOG to monitor stages of sleep and wakefulness during nighttime sleep. The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) provides objective information about sleepiness and selected aspects of sleep structure by measuring eye movements, muscle-tone changes, and brain electrical activity during at least four napping opportunities spread throughout the day. The MSLT takes 8 to 10 hours to complete. Patients wear an Actigraph device on the wrist to measure sleep-wake patterns over an extended period of time. Actigraphy data provide information about sleep time, sleep efficiency, number and duration of awakenings, and levels of activity and rest (Natale et al., 2009).

Insomnia

Insomnia is a symptom that patients experience when they have chronic difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakenings from sleep, and/or a short sleep or nonrestorative sleep (Kryger et al., 2011). It is the most common sleep-related complaint. People with insomnia experience excessive daytime sleepiness and insufficient sleep quantity and quality. However, frequently a patient gets more sleep than he or she realizes. Insomnia often signals an underlying physical or psychological disorder. It occurs more frequently in and is the most common sleep problem for women.

People experience transient insomnia as a result of situational stresses such as family, work, or school problems; jet lag; illness; or loss of a loved one. Insomnia sometimes recurs, but between episodes a patient is able to sleep well. However, a temporary case of insomnia caused by a stressful situation can lead to chronic difficulty in getting enough sleep, perhaps because of the worry and anxiety that develop about getting it.

Insomnia is often associated with poor sleep hygiene, or practices that a patient associates with sleep. If the condition continues, the fear of not being able to sleep is enough to cause wakefulness. During the day people with chronic insomnia feel sleepy, fatigued, depressed, and anxious. Treatment is symptomatic, including improved sleep hygiene measures, biofeedback, cognitive techniques, and relaxation techniques. Behavioral and cognitive therapies have few adverse effects and show evidence of sustained improvement in sleep over time (Babson et al., 2010).

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea is a disorder characterized by the lack of airflow through the nose and mouth for periods of 10 seconds or longer during sleep. There are three types of sleep apnea: central, obstructive, and mixed apnea. The most common form is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Research estimates that 2% to 4% of the adults in the United States meet the diagnostic criteria for OSA (Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force, 2009). The two major risk factors for OSA are obesity and hypertension (Sheldon et al., 2009). Smoking, heart failure, type II diabetes, alcohol, and a positive family history of OSA also greatly increase the risk of developing the problem (Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force, 2009). It occurs in up to 2% of middle-age women and up to 4% of middle-age men, with occurrence higher in the older-adult population and African Americans (Malhotra and Desai, 2010).

OSA occurs when muscles or structures of the oral cavity or throat relax during sleep. The upper airway becomes partially or completely blocked, diminishing nasal airflow (hypopnea) or stopping it (apnea) for as long as 30 seconds (Kryger et al., 2011). The person still attempts to breathe because chest and abdominal movement continue, which often results in loud snoring and snorting sounds. When breathing is partially or completely diminished, each successive diaphragmatic movement becomes stronger until the obstruction is relieved. Structural abnormalities such as a deviated septum, nasal polyps, certain jaw configurations, larger neck circumference, or enlarged tonsils predispose a patient to OSA (Pinto and Caple, 2010). The effort to breathe during sleep results in arousals from deep sleep often to the stage 2 cycle. In severe cases hundreds of hypopnea/apnea episodes occur every hour, resulting in severe interference with deep sleep.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and fatigue are the most common complaints of people with OSA. Persons with severe OSA often report taking daytime naps and experience a disruption in their daily activities because of sleepiness (Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force, 2009). Feelings of sleepiness are usually most intense on awakening, right before going to sleep, and about 12 hours after the midsleep period. EDS often results in impaired waking function, poor work or school performance, accidents while driving or using equipment, and behavioral or emotional problems.

Obstructive apnea causes a serious decline in arterial oxygen saturation level. Patients are at risk for cardiac dysrhythmias, right heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, angina attacks, stroke, and hypertension. Sleep apnea contributes to high blood pressure and increased risk for heart attack and stroke (National Sleep Foundation, 2010b).

Central sleep apnea (CSA) involves dysfunction in the respiratory control center of the brain. The impulse to breathe fails temporarily, and nasal airflow and chest wall movement cease. The oxygen saturation of the blood falls. The condition is common in patients with brainstem injury, muscular dystrophy, and encephalitis. Less than 10% of sleep apnea is predominantly central in origin. People with CSA tend to awaken during sleep and therefore complain of insomnia and EDS. Mild and intermittent snoring is also present.

Patients with sleep apnea rarely achieve deep sleep. In addition to complaints of EDS, sleep attacks, fatigue, morning headaches, irritability, depression, difficulty concentrating, and decreased sex drive are common (Kryger et al., 2011). OSA affects quality of life issues such as marital relationships and interactions within and outside the family and often is an embarrassment to a patient (Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force, 2009). Treatment includes therapy for underlying cardiac or respiratory complications and emotional problems that occur as a result of the symptoms of this disorder.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a dysfunction of mechanisms that regulate sleep and wake states. Excessive daytime sleepiness is the most common complaint associated with this disorder. During the day a person suddenly feels an overwhelming wave of sleepiness and falls asleep; REM sleep occurs within 15 minutes of falling asleep. Cataplexy, or sudden muscle weakness during intense emotions such as anger, sadness, or laughter, occurs at any time during the day. If the cataplectic attack is severe, a patient loses voluntary muscle control and falls to the floor. A person with narcolepsy often has vivid dreams that occur as he or she is falling asleep. These dreams are difficult to distinguish from reality. Sleep paralysis, or the feeling of being unable to move or talk just before waking or falling asleep, is another symptom. Some studies show a genetic link for narcolepsy (Ahmed and Thorpy, 2010).

A person with narcolepsy falls asleep uncontrollably at inappropriate times. When individuals do not understand this disorder, a sleep attack is easily mistaken for laziness, lack of interest in activities, or drunkenness. Typically the symptoms first begin to appear in adolescence and are often confused with the EDS that commonly occurs in teens. Narcoleptic patients are treated with stimulants or wakefulness-promoting agents such as sodium oxybate, modafinil (Provigil) or armodafinil (Nuvigil) that only partially increase wakefulness and reduce sleep attacks. Patients also receive antidepressant medications that suppress cataplexy and the other REM-related symptoms. Brief daytime naps no longer than 20 minutes help reduce subjective feelings of sleepiness. Other management methods that help are following a regular exercise program, practicing good sleep habits, avoiding shifts in sleep, strategically timed daytime naps if possible, eating light meals high in protein, practicing deep breathing, chewing gum, and taking vitamins (Kryger et al., 2011). Patients with narcolepsy need to avoid factors that increase drowsiness (e.g., alcohol; heavy meals; exhausting activities; long-distance driving; and long periods of sitting in hot, stuffy rooms).

Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation is a problem many patients experience as a result of dyssomnia. Causes include symptoms (e.g., fever, difficulty breathing, or pain) caused by illnesses, emotional stress, medications, environmental disturbances (e.g., frequent nursing care), and variability in the timing of sleep because of shift work. Physicians and nurses are particularly prone to sleep deprivation as a result of long work schedules and rotating shifts. Chronic sleep deprivation is associated with development of cardiovascular disease, weight gain, type II diabetes, poor memory, depression, and digestive problems (Ohlmann and O’Sullivan, 2009).

Hospitalization, especially in intensive care units (ICUs), makes patients particularly vulnerable to the extrinsic and circadian sleep disorders that cause the “ICU syndrome of sleep deprivation” (Fontana and Pittiglio, 2010). Constant environmental stimuli within the ICU such as strange noises from equipment, the frequent monitoring and care given by nurses, and ever-present lights confuse patients. Repeated environmental stimuli and the patient’s poor physical status lead to sleep deprivation (Fontana and Pittiglio, 2010).

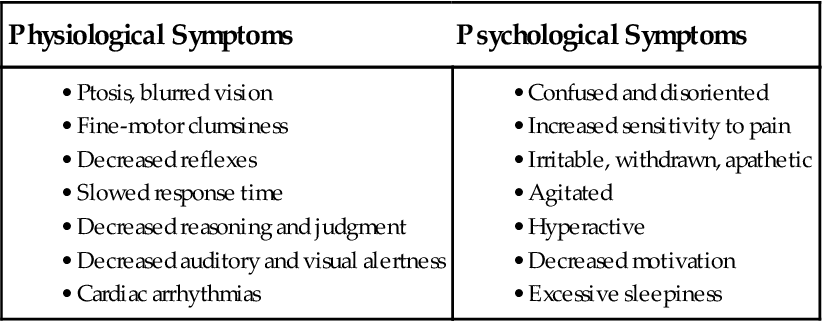

A person’s response to sleep deprivation is highly variable. Patients experience a variety of physiological and psychological symptoms (Box 42-3). The severity of symptoms is often related to the duration of sleep deprivation.

Parasomnias

The parasomnias are sleep problems that are more common in children than adults. Some have hypothesized that sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is thought to be related to apnea, hypoxia, and cardiac arrhythmias caused by abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system that are manifested during sleep (Kryger et al., 2011). Because of an association between the prone position and the occurrence of SIDS, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents place apparently healthy infants in the supine position during sleep (Koren et al., 2010).

Parasomnias that occur among older children include somnambulism (sleepwalking), night terrors, nightmares, nocturnal enuresis (bed-wetting), body rocking, and bruxism (teeth grinding). When adults have these problems, it often indicates more serious disorders. Specific treatment varies. However, in all cases it is important to support patients and maintain their safety.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Sleep and Rest

When people are at rest, they usually feel mentally relaxed, free from anxiety, and physically calm. Rest does not imply inactivity, although everyone often thinks of it as settling down in a comfortable chair or lying in bed. When people are at rest, they are in a state of mental, physical, and spiritual activity that leaves them feeling refreshed, rejuvenated, and ready to resume the activities of the day. People have their own habits for obtaining rest and can find ways to adjust to new environments or conditions that affect the ability to rest. They rest by reading a book, practicing a relaxation exercise, listening to music, taking a long walk, or sitting quietly.

Illness and unfamiliar health care routines easily affect the usual rest and sleep patterns of people entering a hospital or other health care facility. Nurses frequently care for patients who are on bed rest to reduce physical and psychological demands on the body in a variety of health care settings. However, these people do not necessarily feel rested. Some still have emotional worries that prevent complete relaxation. For example, concern over physical limitations or a fear of being unable to return to their usual lifestyle causes such patients to feel stressed and unable to relax. You must always be aware of a patient’s need for rest. A lack of rest for long periods causes illness or worsening of existing illness.

Normal Sleep Requirements and Patterns

Sleep duration and quality vary among people of all age-groups. For example, one person feels adequately rested with 4 hours of sleep, whereas another requires 10 hours. Nurses play an important role in identifying treatable sleep-deprivation problems.

Neonates

The neonate up to the age of 3 months averages about 16 hours of sleep a day, sleeping almost constantly during the first week. The sleep cycle is generally 40 to 50 minutes with wakening occurring after one to two sleep cycles. Approximately 50% of this sleep is REM sleep, which stimulates the higher brain centers. This is essential for development because the neonate is not awake long enough for significant external stimulation.

Infants

Infants usually develop a nighttime pattern of sleep by 3 months of age. The infant normally takes several naps during the day but usually sleeps an average of 8 to 10 hours during the night for a total daily sleep time of 15 hours. About 30% of sleep time is in the REM cycle. Awakening commonly occurs early in the morning, although it is not unusual for an infant to awaken during the night.

Toddlers

By the age of 2 children usually sleep through the night and take daily naps. Total sleep averages 12 hours a day. After 3 years of age children often give up daytime naps (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). It is common for toddlers to awaken during the night. The percentage of REM sleep continues to fall. During this period toddlers may be unwilling to go to bed at night because they need autonomy or fear separation from their parents.

Preschoolers

On average a preschooler sleeps about 12 hours a night (about 20% is REM). By the age of 5 he or she rarely takes daytime naps except in cultures in which a siesta is the custom (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The preschooler usually has difficulty relaxing or quieting down after long, active days and has bedtime fears, awakens during the night, or has nightmares. Partial awakening followed by normal return to sleep is frequent (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). In the awake period the child exhibits brief crying, walking around, unintelligible speech, sleepwalking, or bed-wetting.

School-Age Children

The amount of sleep needed varies during the school years. A 6-year-old averages 11 to 12 hours of sleep nightly, whereas an 11-year-old sleeps about 9 to 10 hours (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The 6- or 7-year-old usually goes to bed with some encouragement or by doing quiet activities. The older child often resists sleeping because he or she is unaware of fatigue or has a need to be independent.

Adolescents

On average teenagers get about  hours of sleep per night. The typical adolescent is subject to a number of changes such as school demands, after-school social activities, and part-time jobs, which reduce the time spent sleeping (Noland et al., 2009). Shortened sleep time often results in EDS, which frequently leads to reduced performance in school, vulnerability to accidents, behavior and mood problems, and increased use of alcohol (Noland et al., 2009; Vallido et al., 2009).

hours of sleep per night. The typical adolescent is subject to a number of changes such as school demands, after-school social activities, and part-time jobs, which reduce the time spent sleeping (Noland et al., 2009). Shortened sleep time often results in EDS, which frequently leads to reduced performance in school, vulnerability to accidents, behavior and mood problems, and increased use of alcohol (Noland et al., 2009; Vallido et al., 2009).

Young Adults

Most young adults average 6 to  hours of sleep a night. Approximately 20% of sleep time is REM sleep, which remains consistent throughout life. It is common for the stresses of jobs, family relationships, and social activities to frequently lead to insomnia and the use of sleep medication. Daytime sleepiness contributes to an increased number of accidents, decreased productivity, and interpersonal problems in this age-group. Pregnancy increases the need for sleep and rest. Insomnia, periodic limb movements, RLS, and sleep-disordered breathing are common problems during the third trimester of pregnancy (Kryger et al., 2011).

hours of sleep a night. Approximately 20% of sleep time is REM sleep, which remains consistent throughout life. It is common for the stresses of jobs, family relationships, and social activities to frequently lead to insomnia and the use of sleep medication. Daytime sleepiness contributes to an increased number of accidents, decreased productivity, and interpersonal problems in this age-group. Pregnancy increases the need for sleep and rest. Insomnia, periodic limb movements, RLS, and sleep-disordered breathing are common problems during the third trimester of pregnancy (Kryger et al., 2011).

Middle Adults

During middle adulthood the total time spent sleeping at night begins to decline. The amount of stage 4 sleep begins to fall, a decline that continues with advancing age. Insomnia is particularly common, probably because of the changes and stresses of middle age. Anxiety, depression, or certain physical illnesses cause sleep disturbances. Women experiencing menopausal symptoms often experience insomnia.

Older Adults

Complaints of sleeping difficulties increase with age. More than 50% of older adults report sleep problems (Neikrug and Ancoli-Israel, 2010). Older adults experience weakening, desynchronized circadian rhythms that alter the sleep-wake cycle (Neikrug and Ancoli-Israel, 2010). Episodes of REM sleep tend to shorten. There is a progressive decrease in stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep; some older adults have almost no stage 4, or deep sleep. An older adult awakens more often during the night, and it takes more time for him or her to fall asleep. The tendency to nap seems to increase progressively with age because of the frequent awakenings experienced at night.

The presence of chronic illness often results in sleep disturbances for the older adult. For example, an older adult with arthritis frequently has difficulty sleeping because of painful joints. Changes in sleep pattern are often caused by changes in the CNS that affect the regulation of sleep. Sensory impairment reduces an older person’s sensitivity to time cues that maintain circadian rhythms.

Factors Influencing Sleep

A number of factors affect the quantity and quality of sleep. Often a single factor is not the only cause for a sleep problem. Physiological, psychological, and environmental factors frequently alter the quality and quantity of sleep.

Drugs and Substances

Sleepiness, insomnia, and fatigue often result as a direct effect of commonly prescribed medications (Box 42-4). These medications alter sleep and weaken daytime alertness, which is problematic (Kryger et al., 2011). Medications prescribed for sleep often cause more problems than benefits. Older adults take a variety of drugs to control or treat chronic illness, and the combined effects of their drugs often seriously disrupt sleep. Some substances such as L-tryptophan, a natural protein found in foods such as milk, cheese, and meats, promote sleep.

Lifestyle

A person’s daily routine influences sleep patterns. An individual working a rotating shift (e.g., 2 weeks of days followed by a week of nights) often has difficulty adjusting to the altered sleep schedule. For example, the body’s internal clock is set at 11 PM, but the work schedule forces sleep at 9 AM instead. The individual is able to sleep only 3 or 4 hours because his or her body clock perceives that it is time to be awake and active. Difficulties maintaining alertness during work time result in decreased and even hazardous performance. After several weeks of working a night shift, a person’s biological clock usually does adjust. Other alterations in routines that disrupt sleep patterns include performing unaccustomed heavy work, engaging in late-night social activities, and changing evening mealtime.

Usual Sleep Patterns

In the past century the amount of sleep obtained nightly by U.S. citizens has decreased to about 6.7 hours per night, causing many Americans to be sleep deprived and experience excessive sleepiness during the day (Ohlmann and O’Sullivan, 2009). Sleepiness becomes pathological when it occurs at times when individuals need or want to be awake. People who experience temporary sleep deprivation as a result of an active social evening or lengthened work schedule usually feel sleepy the next day. However, they are able to overcome these feelings even though they have difficulty performing tasks and remaining attentive. Chronic lack of sleep is much more serious and causes serious alterations in the ability to perform daily functions. Sleepiness tends to be most difficult to overcome during sedentary (inactive) tasks such as driving. There is an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents if an individual drives after less than 7 hours of sleep (Heaton et al., 2009).

Emotional Stress

Worry over personal problems or a situation frequently disrupts sleep. Emotional stress causes a person to be tense and often leads to frustration when sleep does not occur. Stress also causes a person to try too hard to fall asleep, to awaken frequently during the sleep cycle, or to oversleep. Continued stress causes poor sleep habits.

Older patients frequently experience losses that lead to emotional stress such as retirement, physical impairment, or the death of a loved one. Older adults and other individuals who experience depressive mood problems experience delays in falling asleep, earlier appearance of REM sleep, frequent or early awakening, feelings of sleeping poorly, and daytime sleepiness (National Sleep Foundation, 2010c).

Environment

The physical environment in which a person sleeps significantly influences the ability to fall and remain sleep. Good ventilation is essential for restful sleep. The size, firmness, and position of the bed affect the quality of sleep. If a person usually sleeps with another individual, sleeping alone often causes wakefulness. On the other hand, sleeping with a restless or snoring bed partner disrupts sleep.

In hospitals and other inpatient facilities noise creates a problem for patients. Noise in hospitals is usually new or strange and often loud. Thus patients wake easily. This problem is greatest the first night of hospitalization, when patients often experience increased total wake time, increased awakenings, and decreased REM sleep and total sleep time. People-induced noises (e.g., nursing activities) are sources of increased sound levels. ICUs are sources of high noise levels because of staff, monitor alarms, and equipment. Close proximity of patients, noise from confused and ill patients, ringing alarm systems and telephones, and disturbances caused by emergencies make the environment unpleasant. Noise causes increased agitation; delayed healing; impaired immune function; and increased blood pressure, heart rate, and stress (Dennis et al., 2010).

Light levels affect the ability to fall asleep. Some patients prefer a dark room, whereas others such as children or older adults prefer keeping a soft light on during sleep. Patients also have trouble sleeping because of the room temperature. A room that is too warm or too cold often causes a patient to become restless.

Exercise and Fatigue

A person who is moderately fatigued usually achieves restful sleep, especially if the fatigue is the result of enjoyable work or exercise. Exercising 2 hours or more before bedtime allows the body to cool down and maintain a state of fatigue that promotes relaxation. However, excess fatigue resulting from exhausting or stressful work makes falling asleep difficult. This is often seen in grade-school children and adolescents who keep stressful, long schedules because of school, social activities, and work.

Food and Caloric Intake

Following good eating habits is important for proper sleep. Eating a large, heavy, and/or spicy meal at night often results in indigestion that interferes with sleep. Caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine consumed in the evening produce insomnia. Coffee, tea, cola, and chocolate contain caffeine and xanthines that cause sleeplessness. Thus drastically reducing or avoiding these substances can improve sleep. Some food allergies cause insomnia. A milk allergy sometimes causes nighttime waking and crying or colic in infants.

Weight loss or gain influences sleep patterns. Weight gain contributes to OSA because of increased size of the soft tissue structures in the upper airway (Kryger et al., 2011). Weight loss causes insomnia and decreased amounts of sleep (Benca and Schneck, 2005). Certain sleep disorders are the result of the semi-starvation diets popular in a weight-conscious society.

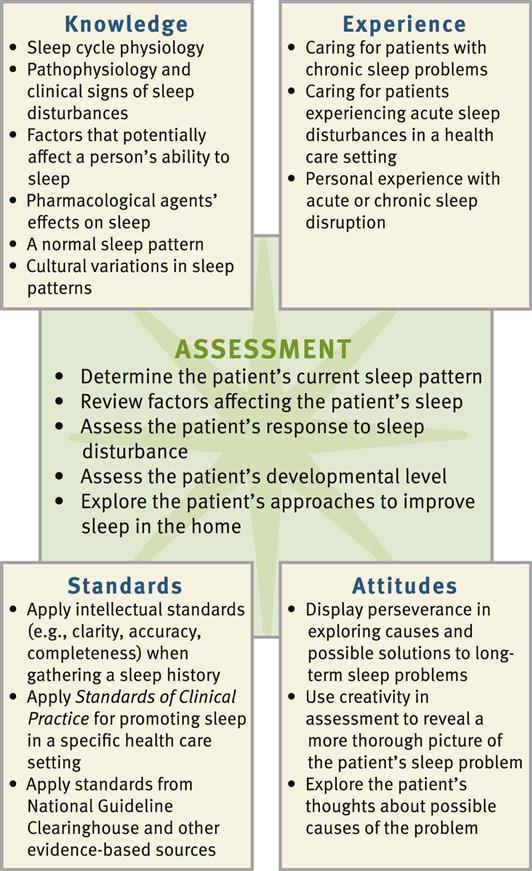

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, including information gathered from patients, experience, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the information necessary, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. You adapt critical thinking to the changing needs of the patient. During assessment (Fig. 42-3) consider all elements to make appropriate nursing diagnoses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree