Sleep and Rest

Objectives

1. Describe normal sleep and rest patterns.

2. Describe how sleep and rest patterns change with aging.

3. Discuss the effects of disease processes on sleep.

4. Describe methods of assessing changes in sleep and rest patterns.

5. Identify older adults who are most at risk for experiencing disturbed sleep patterns.

6. Identify selected nursing diagnoses related to sleep or rest problems.

Key Terms

apnea (ĂP-nē-ă) (p. 330)

boredom (p. 334)

circadian (sĭr-KĀ-dē-ăn) (p. 328)

diurnal ( i-ŬR-năl) (p. 328)

i-ŬR-năl) (p. 328)

fatigue (p. 328)

hypnotic (h p-NŎT-ĭk) (p. 334)

p-NŎT-ĭk) (p. 334)

insomnia (ĭn-SŎM-nē-ă) (p. 329)

nocturnal (nŏ-TŬR-năl) (p. 330)

sedative (SĔD-ă-tĭv) (p. 334)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

Sleep-rest health pattern

The sleep-rest health pattern describes the patterns of sleep, rest, and relaxation that are exhibited throughout the 24-hour day. Individual perceptions, rituals, and aids used to promote sleep and rest are included.

No one knows exactly why we sleep, but it is a fact that we all require sleep to function normally. Sleep apparently allows the body time to rejuvenate and to respond to the stresses of daily living. Lack of adequate sleep can affect health and behavior. Studies have connected sleep deprivation and insomnia to altered appetite; fatigue; decreased ability to perform tasks that require high-level coordination; increased traffic accidents, home accidents, falls, and irritability; emotional instability; difficulty with concentration; and impaired judgment.

Many older people experience problems related to sleep. It is estimated that as many as half of all independent-living older adults and two-thirds of institutionalized older adults have sleep disturbances. Sleep-related problems can be troubling to the aging individual and often are the basis of visits to the physician and complaints to the nurse. Some of these problems result from changes that normally occur with aging; others may be caused or aggravated by acute or chronic health problems. Nurses must understand normal sleep patterns and be able to identify common age-related changes in sleep patterns and common sleep disorders to assess, plan, and intervene appropriately and effectively.

Normal Sleep and Rest

Periods of sleep and wakefulness occur in regular and somewhat predictable cycles. Most humans develop a pattern that repeats approximately every 24 hours. This cycle occurs in response to the day-night cycle of the sun and is referred to as circadian (from the Latin word meaning “about a day”) or diurnal (from the Latin word meaning “daily”) rhythm. Within this cycle, individuals develop their own unique patterns for waking and sleeping.

The usual times that people go to bed and rise differ widely among individuals. Some go to sleep at 10 p.m. and rise at 6 a.m.; others go to sleep at midnight and rise at 8 a.m. These sleep-wake patterns can be disturbed by shift work, time-zone changes, illness, emotional stress, medications, and numerous other factors. The amount of sleep needed also varies widely among individuals. Some individuals function normally with less than 6 hours of sleep, whereas others require 9 hours of sleep or more to feel rested. The average amount of sleep required for people ages 20 to 60 years is 7.5 hours per day.

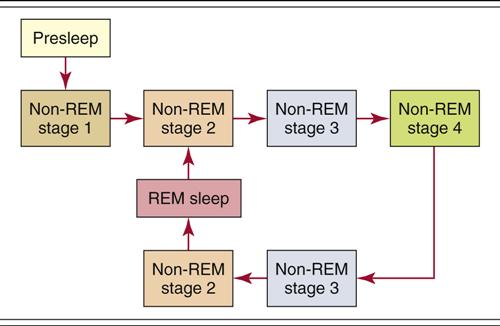

Sleep is under the control of the central nervous system. Current research indicates that wakefulness is regulated by the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. Sleep appears to be controlled by the release of serotonin within the brainstem. Melatonin, which is produced by the pineal gland, is released when the level of light decreases. Levels of cortisol and growth hormone also affect sleep. Sleep is not a uniform state of unconsciousness; rather, it is divided into a series of cycles of lighter and deeper stages of sleep. Immediately before falling asleep, most adults experience a stage of increased relaxation and drowsiness that typically lasts from 10 to 30 minutes. This is followed by four to six complete sleep cycles lasting between 1 and 2 hours each. Each cycle consists of four non-rapid eye movement (NREM) stages and one rapid eye movement (REM) stage (Box 20-1 and Figure 20-1). As the night’s sleep progresses, REM periods increase in length and NREM periods decrease in length. If sleep is interrupted at any time, the individual goes back to stage 1 of NREM sleep and begins a new cycle.

Sleep and Aging

As a person ages, the levels of hormones associated with sleep change. Decreases in melatonin (which regulates the sleep-wake cycle) and growth hormone (which promotes sleep) lead to a shifting in circadian rhythm, causing many elderly people to feel sleepy earlier in the evening and to awake earlier in the morning.

Because sleep efficiency decreases as age increases, many older adults complain that they do not feel refreshed after sleep. Although the amount of time spent in bed may increase with age, the amount of time actually spent sleeping decreases. The average 70-year-old sleeps only 6 hours per night, which is 1.5 hours less than most younger adults sleep. A decreased amount of time is spent sleeping, and the nature of the sleep changes. Older individuals experience more stage 1 and fewer stages 3 and 4 of NREM sleep and somewhat less REM sleep. REM sleep occurs earlier in the sleep cycle than seen in younger adults. These changes result in less deep restorative and refreshing sleep. Circadian rhythm also appears to change with age, resulting in earlier bedtime and earlier rising. It is suspected that this alteration in circadian rhythm is a result of earlier drop in core body temperature, decreased light exposure, or even genetic factors. In addition, sleep interruption and nocturnal awakening are increasingly common because older adults are more easily aroused by environmental noise or stimuli.

Sleep Disorders

Insomnia

The risk for sleep disorders increases with age. Studies show that up to 40% of older individuals report experiencing sleep difficulties at least a few nights each month. The most commonly reported sleep disorder is insomnia, which is defined as difficulty falling asleep or remaining asleep or the belief that one is not getting enough sleep. Insomnia is not a disease in itself but rather a symptom of some other underlying problem. Different types of insomnia are identified based on the phase of sleep affected: (1) sleep initiation problems—those related to falling asleep, (2) sleep maintenance problems—those related to staying asleep, or (3) terminal insomnia problems—those related to abnormally early awakening. Identification of the type of insomnia problem can help nurses identify the underlying cause or causes and result in the best interventions.

Older individuals with existing health problems are more likely to experience sleep problems than those who report themselves to be in good health. Insomnia can be related to a variety of medical conditions, medications, and psychological, behavioral, or environmental factors. Medical conditions that cause pain, interfere with breathing, or cause frequent bladder or bowel elimination can contribute to frequent awakening. Common medical problems that may lead to insomnia include arthritis, bursitis, gastroesophageal reflux, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, sleep apnea, prostatic problems, cystitis, and others. Nocturnal movement disorders, including restless leg syndrome (RLS), which is an irresistible urge to move the lower extremities, or nocturnal myoclonus, which causes sudden repetitive jerking or kicking movements of the lower extremities, can also contribute to insomnia in older adults.

Anxiety is likely to be related to difficulty falling asleep and interrupted sleep. Depression is most likely to be associated with early awakening but may also be related to hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness at a time of normal wakefulness). People with dementia often experience abnormal sleep cycles and are prone to waking and wandering during the night. Both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications are likely to affect sleep in older adults (Table 20-1). Some medications make falling asleep more difficult, whereas others cause frequent awakening (Box 20-2). A few medications can result in hypersomnolent responses.

![]() Table 20-1

Table 20-1

Characteristics of Selected Medications Used to Promote Sleep

| Classification | Examples | Precautions |

| Sedative/hypnotics GABA receptor agents | Zolpidem tartrate | May cause morning drowsiness, headache, hangover, dizziness, or paradoxic excitement |

| Benzodiazepines | Flurazepam, temazepam, estazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam | Likely to cause daytime sedation and short-term memory impairment in older adults, particularly with long-acting forms; associated with increased risk for falls; paradoxic excitement may occur; must be avoided in individuals with sleep apnea; legislation restricts use in nursing home settings |

| Tricyclic | Diphenhydramine | May result in agitation, confusion, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention, and arrhythmias; can make the quality of sleep less restful; not preferred for older adults |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline | Potential side effects include urinary retention, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, and confusion; risk for cardiac arrhythmias, fatigue, headache, blood dyscrasias, altered blood glucose readings, nausea, and photosensitivity |

| Antidepressants SSRI, MAOI | Imipramine, Fluoxetine, Buspirone | Affect amount (increase or decrease) of REM sleep; danger of overdose; daytime hangover; |

| Others | Chloral hydrate Barbiturates such as phenobarbital | Sedation with hangover effects; severe interaction with other sedatives; gastrointestinal toxicity. Addictions; loss of effectiveness with chronic use; low lethal dose |

Modified from Pagel JF and Parnes BL: Medications for the treatment of sleep disorders, Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 3(3), 2001.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree