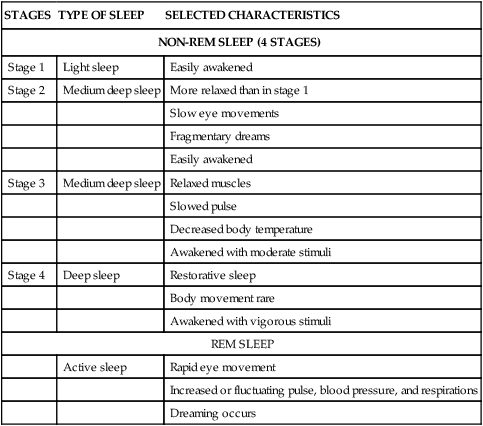

Sue E. Meiner, EdD, APRN, BC, GNP On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify three age-related changes in sleep. 2. Describe the features of insomnia. 3. Discuss four factors influencing sleep in older adults. 4. Discuss two sleep disorders. 5. List four components of a sleep history. 6. Describe three sleep hygiene measures. 7. Describe the effects of lifestyle changes on sleep and activity in older adults. 8. Define basic and instrumental activities of daily living. 9. Discuss the benefits of physical activity for older adults. 10. Identify three characteristics of meaningful activities for older adults with dementia. Normal sleep is divided into rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and four stages of non-REM sleep (Table 11–1). Non-REM sleep accounts for about 75% to 80% of sleep (Burke & Laramie, 2004; Hoffman, 2003). The remaining 20% to 25% of sleep is REM sleep. A night’s sleep begins with the four stages of non-REM sleep, continues with a period of REM sleep, and then cycles through non-REM and REM stages of sleep for the rest of the night. Sleep cycles range from 70 to 120 minutes in length, with four to six cycles occurring in a night. TABLE 11–1 Modified from Ebersole P, Hess P, Touhy T, et al: Toward healthy aging, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby. Stage 1 of non-REM sleep is the lightest level of sleep. During stage 1 an individual can be easily awakened. Sleep progressively deepens during stages 2 and 3 until stage 4, the deepest level, is reached. Muscle tone, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory rate are reduced in stage 4 (Hoffman, 2003). In REM sleep, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory rate increase (Burke & Laramie, 2004). The REMs of this stage are associated with dreaming. When the amount of REM sleep is reduced, an individual may experience difficulty concentrating, irritability, or anxiety the next day. Variations in the REM and non-REM sleep stages occur with advancing age. REM sleep is interrupted by more frequent nocturnal awakenings, and the total amount of REM sleep is reduced. The amount of stage 1 sleep is increased, and stage 3 sleep and stage 4 sleep are less deep. In the very old, especially men, the amount of slow wave sleep as determined by electroencephalogram (EEG) is greatly reduced (Kryger, Monjan, Bliwise, & Ancoli-Israel, 2004). The sleep–wake cycle follows a circadian rhythm, which is roughly a 24-hour period. The hypothalamus controls many circadian rhythms, which include the release of certain hormones during sleep. Numerous factors can gradually strengthen or weaken the sleep and wake aspects of circadian rhythm, including the perception of time, travel across time zones, light exposure, seasonal changes, living habits, stress, illness, and medication (Hoffman, 2003). The decrease in nighttime sleep and the increase in daytime napping that accompanies normal aging may result from changes in the circadian aspect of sleep regulation (Cohen-Zion & Ancoli-Israel, 2003; Lewy, 2009). Insomnia, the inability to sleep, is a complex phenomenon. Reports of insomnia include difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, early morning awakening, and daytime somnolence. Insomnia may be transient, short term, or chronic (Beers & Berkow, 2000). Transient insomnia lasts only a few nights and is related to situational stresses. Short-term insomnia usually lasts less than a month and is related to acute medical or psychologic conditions such as postoperative pain or grief. Chronic insomnia lasts more than a month and is related to age-related changes in sleep, medical or psychologic conditions, or environmental factors. Insomnia may affect the older adult’s quality of life with excessive daytime sleepiness, attention and memory problems, depressed mood, nighttime falls, and possible overuse of hypnotic or over-the-counter medications (Kryger et al, 2004). Many older adults experience changes in sleep, which are considered “normal” age-related changes (Box 11–1). However, while some older adults either do not experience these common changes or do not consider them sources of distress, other adults find these changes problematic (Beers & Berkow, 2000). The sleep changes experienced by many older adults include increased sleep latency, reduced sleep efficiency, more awakenings in the night, increased early morning awakenings, and increased daytime sleepiness (Hoffman, 2003). Sleep latency, a delay in the onset of sleep, increases with age. Older adults report that it takes longer to fall asleep at the start of the night and after being awakened during the night. Because the time spent awake in bed trying to fall asleep increases, sleep efficiency decreases. Sleep efficiency is the relative percentage of time in bed spent asleep. For young adults sleep efficiency is approximately 90%. However, this percentage drops to 75% for older adults (Hoffman, 2003). Nocturnal awakenings contribute to an overall decrease in the average number of hours of sleep. The frequency of nocturnal awakenings increases with age. The interruptions of sleep contribute to the perception that the amount of sleep is inadequate or of poor quality. If the person has little difficulty falling back to sleep, the decrease in the number of hours of sleep may be slight. However, some older adults report increased periods of wakefulness after nocturnal awakening. The reasons for nocturnal awakening include trips to the bathroom, dyspnea, chest pain, arthritis pain, coughing, snoring, leg cramps, and noise (Beers & Berkow, 2000). Early morning awakening and the inability to fall back to sleep may be related to changes in circadian rhythm or to any of the reasons for nocturnal awakening. Daytime sleepiness is often reported by older adults and may be due to frequent nocturnal awakening or other sleep disturbances. However, in some older adults, daytime sleepiness suggests underlying disease, contributes to the risk of motor vehicle accidents, and, when cognitive dysfunction is present, is a predictor of mortality (Whitney et al, 1998). Daytime sleepiness may also be due to medication side effects. Although some of the sleep changes experienced by older adults are related to aging, other sleep changes are associated with chronic disease and other health problems. When patterns of sleep are examined, an increase in light sleep is seen as deep sleep declines. The loss of deep sleep is associated with stages 3 and 4 of sleep (see Table 11–1). This sleep disturbance may be a normal part of aging due to changes in the reticular formation (RF) in the brain (Friedman, 2006). When older adults describe the ways their sleep has changed as they have aged, they offer nurses valuable clues. Their descriptions indicate health problems (actual or potential), safety concerns, and possible interventions to improve sleep quality. The environment can positively or negatively influence a person’s quality and amount of sleep. For older adults, environments conducive to relaxation are likely to be soporific. Such environments include low levels of stimuli, dimmed lights, silence, and comfortable furniture (Rosto, 2001). The environment of a health care institution can detract from the quality of sleep. Not only are these environments unfamiliar but they also typically have bright lights, noisy people and machines, limited privacy and space, and uncomfortable mattresses. There may be physical discomfort or pain from invasive procedures such as Foley catheterization, intravenous line placement, venipuncture, or mechanical ventilation or discomfort or pain from equipment such as oxygen masks, casts or traction devices, and monitors. The hospital patient or long-term care facility resident is often awakened to receive medications or treatments or to be assessed for changes in vital signs and condition. Nocturnal awakenings for incontinence care or for other care procedures such as repositioning and skin care interrupt the normal sequence of sleep stages (Nagel et al, 2003). Fear of the unexpected or unknown may also keep older adults awake in health care institutions. The quality of sleep in institutional settings improves as nursing interventions address (1) the scheduling of procedures and care activities to avoid unnecessary awakenings, (2) modification of environmental factors to promote a quiet, warm, relaxed sleep setting, and (3) orientation of older adults to the institutional setting. Environmental noise potentially interferes with sleep in all health care settings. The consequences of environmental noise can include (1) sleep deprivation, (2) alteration in comfort, (3) pain, and (4) stress or difficulty concentrating, which can interfere with the enjoyment of activities. Sources of noise include personnel, roommates, visitors, equipment, and routine activities on the nursing unit (Box 11–2). Interventions to reduce environmental noise include closing the doors of client and resident rooms when possible, adjusting the volume control on telephones, rescheduling nighttime cleaning routines, and reminding staff and visitors to speak quietly. Some older adults may appreciate headphones to provide relaxing music and block background noise. Headphones will also reduce noise from late evening television watching. Noise reduction may include asking the facility’s maintenance staff to clean and lubricate the wheels on all of the unit’s utility carts. Reducing environmental noise in institutions involves cooperation among employees from other departments, visitors, and nurses. Falling asleep and staying asleep is difficult when a person is cold. Older adults may wake during the night because of a nighttime reduction in core body temperature related to a reduced metabolic rate and reduced muscle activity. Being too warm will also disrupt sleep, but some older adults sleep better if simple measures are used to keep them warm. The ambient temperature of the bedroom should be no lower than 65° F (Worfolk, 1997). Several light thermal blankets and flannel sheets (both fitted and flat) make for a warmer bed. Flannel pajamas or nightgowns, bed socks, and nightcaps help sleepers stay warm. If bed socks are worn, slippers should be used when out of bed to prevent slipping on uncarpeted floors. Heating devices such as heating pads or hot water bottles should be avoided so that the fragile skin on the feet and lower legs is not thermally injured. Body pain, acute or chronic, interferes with falling asleep and with staying asleep. Nursing interventions to relieve pain begin with assessment of the location, severity, and type of pain and any aggravating or alleviating factors (see Chapter 15). The effect of the pain on older adults’ lifestyles, including sleep quality, should also be assessed. Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures may be used to relieve pain. When body pain interferes with sleep, analgesics are more effective for sleep promotion than sedative or hypnotic medications. However, the alterations in pharmacokinetics that are common to older adults taking medication make the careful selection of analgesics important. Drugs with long half-lives linger longer in many older adults. Small initial doses that may be titrated upward to achieve analgesia may be better tolerated than generous initial doses. Attention must be paid to common side effects such as constipation. Widowhood is a common life event in the older adult population. For older women, widowhood is much more common than it is for older men. Half (50%) of women older than 65 are widows, while only 12% of men are widowers (deVries, 2001). Widowhood leaves older adults without “touch partners.” Loss of a bed partner can make sleep psychologically less comforting. Older widows and widowers describe the strangeness of going to bed alone after many years of marriage. This change in bedtime routine may interfere with the onset of sleep. If the widow or widower experiences depression, the depression should be treated. The standard advice is to avoid caffeine-containing beverages for several hours before going to bed. This diminishes the likelihood that the stimulant effect of caffeine will interfere with falling asleep and staying asleep. Other sources of caffeine include hot chocolate, chocolate candy, some over-the-counter pain analgesics and cold remedies, and some brands of decaffeinated tea and coffee (Cochran, 2003). Some herbal products also contain caffeine. Alternative choices for late evening beverages are fruit juices, milk, and water. Alcohol occupies an equivocal position among beverages that influence sleep. Many adults include alcohol as part of their normal lifestyle and continue to do so in advancing age. They enjoy a glass of wine or sherry with an evening meal or an occasional beer or mixed drink. Small amounts of alcoholic beverages may cause a slight drowsiness or a relaxation that promotes falling asleep. However, larger amounts of alcohol reduce the amount of both REM sleep and deep sleep and impair the overall quality of a night’s sleep (Burke & Laramie, 2004). The diuresis caused by alcohol-induced inhibition of antidiuretic hormone secretion leads to nocturnal awakenings for urination. When discussing the use of alcohol with older adults, the nurse must determine how they define a “small” or “large” amount of alcohol and the circumstances of alcohol use. These details of alcohol use vary from group to group and from culture to culture (see Chapter 18). Hunger and thirst can be causes of sleeplessness. Bedtime snacks and small amounts of liquids may provide the touch of comfort that promotes sleep. Warm snacks containing protein are better at bedtime than cold snacks (Cochran, 2003). Milk, eggnog, creamed soup, or flavored gelatin may all be served hot to provide warmth and calories. Pudding, custard, or tapioca may be more palatable than crackers or graham crackers. For older adults with diabetes, bedtime snacks should be included in their diabetic diets. Falling back to sleep after awakening during the night with a dry mouth is facilitated when there is a cup of water close to the bed. Medications are often used to treat insomnia, although there are also nonpharmacologic interventions for insomnia. Tranquilizers and sedatives decrease activity and calm the recipient. Sleep may follow the calming effect. Hypnotics produce drowsiness and facilitate the onset and maintenance of sleep by causing central nervous system depression. Hypnotics should be used only for a short course of therapy (3 weeks or less) or for intermittent use in chronic insomnia (once every 2 or 3 nights) (Cochran, 2003). Long-term use of hypnotics may lead to tolerance of the drug and rebound insomnia (Hill-O’Neill & Shaughnessy, 2002). When selecting a medication to promote sleep, nurses should avoid barbiturates, chloral hydrate, antihistamines, and over-the-counter preparations because of their side effects (Beers & Berkow, 2000). Benzodiazepines are the most commonly prescribed hypnotics for the older adult because of the safety profile and efficacy of the medications (Cochran, 2003). Benzodiazepines alter both non-REM and REM sleep and increase the total sleep time. When benzodiazepines are used in older adults, the risk of side effects is increased because some benzodiazepines have long half-lives and active metabolites that prolong the sedating effect of the drug (Beers & Berkow, 2000). Age-related changes in the clearance of benzodiazepines increase the risk of prolonged sedation. Complications of benzodiazepine use include daytime drowsiness, increased risk of falls during the night or in the early morning, confusion, and disorientation. Many medications, prescription and over-the-counter, have drowsiness as a side effect. While this side effect may be welcomed as a benefit beyond the intended therapeutic purpose of the medication, the use of these medications to induce sleep is problematic. Some of these medications have other side effects that negate the sleep-inducing benefit. Two types of medications will serve as examples: antihistamines and tricyclic antidepressants (Cohen-Zion & Ancoli-Israel, 2003). While drowsiness is one side effect of antihistamines, the other side effects include increased intraocular pressure; dry mouth; constipation; urinary retention; and, paradoxically, confusion, agitation, restlessness, and insomnia. As another example, tricyclic antidepressants may be slightly sedating but may also cause insomnia and nightmares (see Chapter 22). Several types of medications have insomnia as a side effect or have side effects that lead to disturbed sleep or nocturnal awakening (Table 11–2). Over-the-counter medications that interfere with sleep include nasal decongestants containing amphetamine-like substances and analgesics containing caffeine. Many prescription medications have side effects that affect sleep. TABLE 11–2 EXAMPLES OF MEDICATIONS THAT DISTURB SLEEP Compiled from Beers MH, Berkow R: The Merck manual of geriatrics, ed 3, Whitehouse Station, NH, 2000–2006, Merck Research Laboratories; Foreman MD, Wykle M: Nursing standard-of-practice protocol: sleep disturbances in elderly patients, Geriatr Nurs 16:238, 1995; and Tatro DS, editor: Nurses drug facts, St Louis, 1996, Facts & Comparisons. Various natural or herbal remedies have been recommended as aids for securing a good night’s sleep. Unlike prescription drugs, the composition of these compounds is not readily available, and their side effects and interactions with prescription or over-the-counter drugs have not been fully explored (Box 11–3). However, because some herbal remedies contain active ingredients that resemble prescription and over-the counter drugs, some risk for drug–drug interaction exists (Cochran, 2003).

Sleep and Activity

Sleep and Older Adults

Biologic Brain Functions Responsible for Sleep

Stages of Sleep

STAGES

TYPE OF SLEEP

SELECTED CHARACTERISTICS

NON-REM SLEEP (4 STAGES)

Stage 1

Light sleep

Easily awakened

Stage 2

Medium deep sleep

More relaxed than in stage 1

Slow eye movements

Fragmentary dreams

Easily awakened

Stage 3

Medium deep sleep

Relaxed muscles

Slowed pulse

Decreased body temperature

Awakened with moderate stimuli

Stage 4

Deep sleep

Restorative sleep

Body movement rare

Awakened with vigorous stimuli

REM SLEEP

Active sleep

Rapid eye movement

Increased or fluctuating pulse, blood pressure, and respirations

Dreaming occurs

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

Insomnia

Age-Related Changes in Sleep

Factors Affecting Sleep

Environment

Hospitals and long-term care facilities

Noise

Temperature

Pain and Discomfort

Lifestyle Changes

Loss of spouse

Dietary Influences

Drugs Influencing Sleep

Drugs used to promote sleep

Drugs with drowsiness as a side effect

Drugs causing insomnia or sleep disturbances

TYPE OF SLEEP DISTURBANCE

EXAMPLES OF MEDICATIONS

Alteration of REM sleep

Alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines

Insomnia

Haloperidol, risperidone, phenytoin, sertraline, theophylline, amitriptyline

Delayed onset of sleep

Caffeine, amphetamines, theophylline, nasal decongestants containing stimulants

Nocturnal awakening

Diuretics

Nightmares, vivid dreams

Atenolol, nifedipine, carbidopa-levadopa, propranolol, amitriptyline

Daytime sleepiness

Antipsychotics (haloperidol, risperidone), long-acting benzodiazepines, cold remedies containing antihistamines, atenolol, diltiazem, nifedipine, ranitidine, cimetidine

Natural or herbal remedies

Sleep and Activity

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access