1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive sexual responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with sexual responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to sexual responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to sexual responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to sexual responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to sexual responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to sexual responses. 8. Develop a patient education plan to promote adaptive sexual responses. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to sexual responses. 1. Genetic identity, which is a person’s chromosomal gender 2. Gender identity, which is a person’s perception of his or her own maleness or femaleness 3. Gender role, which is the cultural role attributes of a person’s gender, such as expectations regarding behavior, cognitions, occupations, values, and emotional responses 4. Sexual orientation, which is the gender to which a person is romantically attracted are often called on to intervene in the sexual concerns of patients when providing holistic patient care. It is important to develop skills and competence in addressing sexual issues by increasing awareness through education. Nurses need the following in relation to sexuality: • Awareness of their own sexual feelings and values • Education about all aspects of sexuality to provide quality patient care • Understanding that many patients may have beliefs, feelings, and values that differ from their own On a continuum, sexuality ranges from adaptive to maladaptive (Figure 25-1). Adaptive responses meet the following criteria: • Between two consenting adults • Not psychologically or physically harmful to either • Lacking in force or coercion Caution must be used when attempting to label sexual behaviors as adaptive or maladaptive. Disagreements and exceptions to the rule will always exist. The continuum shown in Figure 25-1 is free of moral judgment and was constructed to help the nurse develop self-awareness and understand the range of sexual responses. The first step in developing self-awareness involves clarification of values regarding human sexuality. Figure 25-2 illustrates four phases of the nurse’s growth: cognitive dissonance, anxiety, anger, and action (Foley and Davies, 1983). • Data inquiry occurs when the nurse seeks out additional information about sexual issues. After the information is obtained, the nurse may discuss and debate the issues. • These are healthy ways of exploring and deciding what to believe, and the nurse will eventually make some choices about a value position. • The final behavior is prizing the value position, in which the nurse is willing to share it publicly. Although prizing values is the final step in a positive growth experience, it does not mean that what is valued will not change. Values are never static; they evolve and shift as a person changes, grows, and has new experiences. A person who once opposed abortion may later become understanding and empathetic toward women who have abortions. The next clinical example shows the growth health professionals experience while increasing their awareness about sexuality. Chapter 2 has additional content on developing self-awareness and the nurse’s therapeutic use of self. Effective interviewing skills are an essential part of a sexual assessment (Magnan and Norris, 2008; Zakhari, 2009; Jaarsma et al, 2010). Nurses sometimes may be uncomfortable addressing sexual issues. However, the principles of effective interviewing are the same even when addressing sexual issues. • Tell me what you understand about (menstruation, intercourse, sexual changes with aging, menopause). • Since you’ve been diagnosed, what questions have you had regarding your sexuality? • Are there any changes you have noticed in your sexual patterns since becoming ill? • Have you noticed any differences or problems in your sexual responses since taking this medication? • Often people have questions about masturbation, sexual frequency, safe sex, alternate positions. Do you? • Sometimes it is uncomfortable to talk about sexual issues with your partner. How is this for you and your partner? There are many types of sexual expression. In a classic work, Kinsey et al (1953) suggested that most people are not exclusively heterosexual or homosexual. Their studies indicated that a substantial percentage of men and women had experienced both heterosexual and homosexual activity. An individual’s attraction to people of the same gender, opposite gender, or both genders is called sexual orientation or sexual preference. Some prefer the term sexual orientation to sexual preference because preference implies that homosexuals choose to be homosexual. Although sexual behaviors do involve choice, research has indicated that sexual orientation is affected by genetics and biochemical events (Blanchard, 2008; Francis, 2008; Hall and Schaeff, 2008; Miller et al, 2008; Bogaert, 2010). It is difficult to estimate the actual incidence of homosexuality in the United States. The estimates have ranged from 2% to 6% of the population (McCabe, 2009). However, many people have had a sexual experience with a member of the same gender at one time in their lives, and this is typically not identified when surveys are taken. One of the reasons that it is difficult to obtain an accurate incidence of homosexuality is that social stigma is still attached to labeling oneself as homosexual, and it is possible that many individuals do not report their true sexual identity. In addition to modes of sexual expression or sexual orientation, the physiological and psychological responses to sexual stimulation can be described. The four stages of the sexual response cycle are desire, excitement, orgasm, and resolution (Box 25-1). Experts have begun to look at the lack of research regarding female sexual response. It is commonly believed that female sexual functioning is more complicated than and not as linear as male sexual functioning (Kingsburg and Althof, 2009; Sobczak, 2009a; Jordan et al, 2011). Men and women experience sexual dysfunctions very differently. Men are more likely to report problems with sexual performance and erectile dysfunction (Diaz and Close, 2010), including difficulty with obtaining or maintaining an erection and premature or delayed ejaculation. Women are motivated to seek help for concerns about sexual feelings, including lack of desire or sexual pleasure (Leiblum, 2007; Jordan et al, 2011). • Women are more likely to report sexual inhibitions and relationship problems. They also experience flashbacks, dissociative episodes, feelings of shame and guilt, compulsive sexual behavior, and sexual aversion. • Men who were sexually abused as children often demonstrate sexually aggressive behavior, multiple sexual partners, fear of intimacy, compulsive sexual behavior, and confusion about their sexual orientation. For both women and men, sexual dysfunction is more likely to be found when the incidence of abusive episodes is high and the types of abuse are many. The care of people who have experienced abuse and violence is described in detail in Chapter 38. Gynecological conditions also can contribute to sexual difficulties. Hysterectomy, gynecological malignancies, and breast cancer present medical and mortality concerns and may alter perceptions of femininity that may result in decreased sexuality (Hughes, 2008). Normal changes in a woman’s reproductive life related to puberty, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause can present unique problems. Puberty may lead to concerns regarding sexual identity. Pregnancy and the postpartum period are often associated with a decrease in sexual activity, desire, and satisfaction, which may be prolonged with lactation. The state of menopause may result in physical changes, alterations in mood, and decreased libido (Woods et al, 2010). As women age, they may also experience a decline in desire and frequency of intercourse. Psychiatric illness affects a person’s sexuality and the sexual behavior and satisfaction of the person’s partner (Box 25-2). In a study of inpatients with a psychiatric illness, 71% reported an impairment in their sexuality. Although sexual dysfunction was found in all diagnostic groups, it was particularly prevalent among those with depression (Cohen et al, 2007). A study examining the sexual needs and relationship experiences of patients with schizophrenia revealed that 83% were currently experiencing sexual feelings and had a need for an intimate relationship. Unfortunately, only 10% of the staff recognized the need for sexual expression in their patients (McCann, 2010). These findings support the need for a discussion of sexuality as an integral part of treatment. The sexual side effects of psychiatric medications are well documented. In a study of men and women with schizophrenia, 52% reported a sexual dysfunction. No differences were reported for the atypical, conventional, and combination antipsychotics (Ucok et al, 2007). Sexual dysfunctions are a common side effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These antidepressants can cause problems in any phase of the sexual response cycle. Although stopping the drugs for a specified period, sometimes known as drug holidays, has been proposed to treat these problems, drug holidays may lead to decreased efficacy and noncompliance with treatment. Alternatively, other antidepressant agents or additional medications can be used to treat the dysfunction. Psychiatric medications and their side effects are described in Chapter 26. • Reducing the number of sexual partners • Promoting sexual behaviors that decrease the exchange of body fluids In contrast, the number of people living with AIDS has increased. From 2006 through 2008, the rate per 100,000 of people living with AIDS was lowest among people younger than age 20 and older than age 65 years, but the number of persons diagnosed with HIV who are middle aged is concerning. In 2008, 41% of people living with AIDS were between the ages of 40 and 49 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Although the success of treatment for AIDS is promising, the effects of this illness have a significant impact on all aspects of society. Many people infected with HIV also may have psychiatric and drug dependence problems and may experience more problems with HIV care (Fremont et al, 2007; Dyer and McGuinness, 2008). Nurses and other health care providers need to actively identify those at risk and work with clinicians and policymakers to ensure the availability of appropriate testing, counseling, and treatment for these individuals. Advanced practice nurses can be particularly effective in delivering community-based care in tailored interventions to improve outcomes of individuals with HIV and co-occurring serious mental illness (Blank et al, 2011).

Sexual Responses and Sexual Disorders

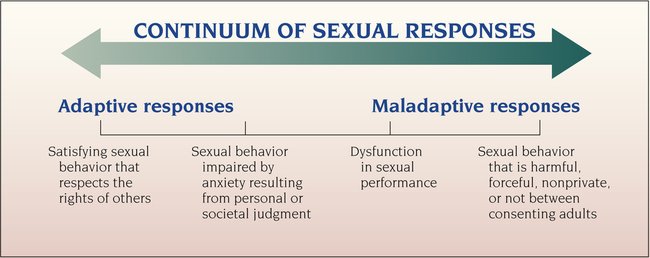

Continuum of Sexual Responses

Adaptive and Maladaptive Sexual Responses

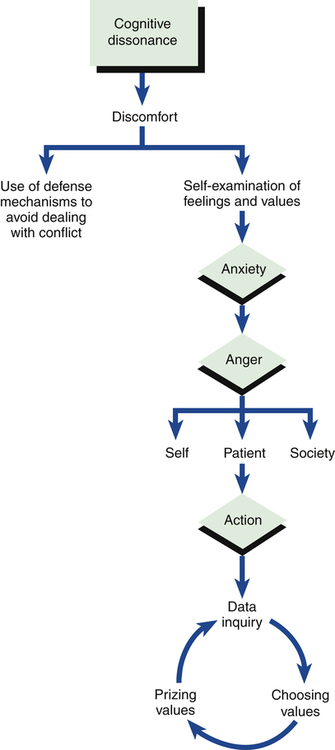

Self-Awareness of the Nurse

Action

Assessment

Behaviors

Homosexuality

The Sexual Response Cycle

Predisposing Factors

Biological Factors

Behavioral Factors

Precipitating Stressors

Physical Illness and Injury

Psychiatric Illness

Medications

HIV/AIDS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sexual Responses and Sexual Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access