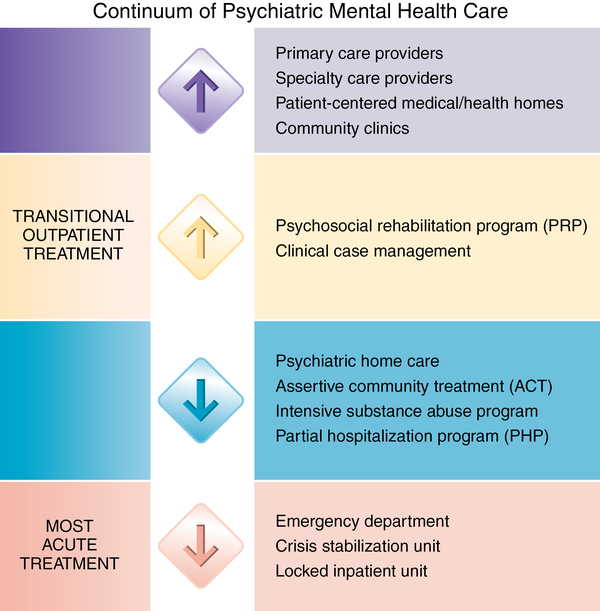

CHAPTER 4 Monica J. Halter, Christine Tebaldi and Avni Cirpili 1. Compare the process of obtaining care for physical problems with obtaining care for psychiatric problems. 2. Analyze the continuum of psychiatric care and the variety of care options available. 3. Describe the role of the primary care provider and the psychiatric specialist in treating psychiatric disorders. 4. Explain the purpose of patient-centered medical homes and implications for holistically treating individuals with psychiatric disorders. 5. Evaluate the role of community mental centers in the provision of community-based care. 6. Identify the conditions that must be met for reimbursement of psychiatric home care. 7. Discuss other community-based care providers including assertive community treatment (ACT) teams, partial hospitalization programs, and alternate delivery of care methods such as telepsychiatry. 8. Describe the nursing process as it pertains to outpatient settings. 9. List the standard admission criteria for inpatient hospitalization. 10. Discuss the purpose of identifying the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients. 11. Explain how the multidisciplinary treatment team collaborates to plan and implement care for the hospitalized patient. 12. Discuss the process for preparing patients to return to the community for ongoing care and for promoting the continuation of treatment. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of this system, to briefly examine the evolution of mental health care, and to explore different venues by which people receive treatment for mental health problems. Treatment options are roughly presented in order of acuteness, beginning with those in the least restrictive environment, or the setting that provides the necessary care allowing the greatest personal freedom. This chapter also explores funding sources for mental health care. Box 4-1 introduces the idea of influencing health care through advocacy initiatives. What if you, your friend, or a family member needed psychiatric treatment or care? What would you do or recommend? Figure 4-1 presents a continuum of psychiatric mental health care that may help you to make a decision. Movement along the continuum is fluid and can go in either direction. For example, patients discharged from acute hospital care or a 24-hour supervised crisis stabilization unit (most acute level), may need intensive services to maintain their initial gains or to “step down” in care. Failure to follow up in outpatient treatment increases the likelihood of rehospitalization and other adverse outcomes. Patients may pass through the continuum of treatment in the reverse direction; that is, if symptoms do not improve, a lower-intensity service may refer the patient to a higher level of care in an attempt to prevent total decompensation (deterioration of mental health) and hospitalization. Accessibility to service is central to this model. Imagine a system with shorter waiting time for urgent care, expanded clinical hours, and 24/7 telephone or electronic access to real people on the care team. The use of health information technology is also an essential aspect of this care (Meyers et al., 2010). Electronic health records will undoubtedly help these centers of care fully reach their potential. Community mental health centers were created in the 1960s and have since become the mainstay for those who have no access to private mental health care (Drake & Latimer, 2012). The range of services available at such centers varies, but generally they provide emergency services, adult services, and children’s services. Common treatments include medication administration, individual therapy, psychoeducational and therapy groups, family therapy, and dual-diagnosis (mental health and substance abuse) treatment. A clinic may also be aligned with a psychosocial rehabilitation program that offers a structured day program, vocational services, and residential services. Some community mental health centers have an associated intensive psychiatric case management service to assist patients in finding housing or obtaining entitlements. Boundaries become important in the home setting. Walking into a person’s home creates a different set of dynamics than those commonly seen in a clinical setting. It may be important for the nurse to begin a visit informally by chatting about patient family events or accepting refreshments offered. Continuity of care in this type of situation can increase the level of comfort and has been shown to decrease levels of depression and anxiety (D’Errico & Lewis, 2010). There is great significance to the therapeutic use of self in such circumstances to establish a level of comfort for the patient and family; however, nurses must be aware of the boundaries between a professional relationship and a personal one. (See the vignette at the top of the next column.) Assertive community treatment (ACT) is an intensive type of case management developed in the 1970s in response to the oftentimes hard to engage, community-living needs of people with serious, persistent psychiatric symptoms and patterns of repeated hospitalization for services such as emergency room and inpatient care (Wright-Berryman, McGuire, & Salyers, 2011). Patients are referred to ACT teams by inpatient or outpatient providers because of a pattern of repeated hospitalizations with severe symptoms, along with an inability to participate in traditional treatment. ACT teams work intensively with patients in their homes or in agencies, hospitals, and clinics—whatever settings patients find themselves in. Creative problem solving and interventions are hallmarks of care provided by mobile teams. The ACT concept takes into account that people need support and resources after 5:00 pm; teams are on call 24 hours a day. Telephone crisis counseling, telephone outreach, and the Internet are being used to enhance access to mental health services. Although face-to-face interaction is still preferred, the new forms of treatment through technology, such as telepsychiatry, have shown immense patient satisfaction and no evidence of complications (Garcia-Lizana & Munoz-Mayorga, 2010). Access and overall health outcomes are expected to improve as models of care that include telehealth and other innovative practices advance. Secondary prevention is also aimed at reducing the prevalence, or number of new and old cases at any point in time, of psychiatric disorders. Early identification of problems, screening, and prompt and effective treatment are hallmarks of this level. According to the Institute of Medicine (Katz & Ali, 2009), this level of prevention is the secondary defense against disease. While it does not stop the actual disorder from beginning, it may delay or avert progression to the symptomatic stage. For example, psychiatric needs are well known in the criminal justice system and the homeless population. Individuals suffering from a serious mental illness tend to cycle through the correctional systems and generally comprise more than 50% of the incarcerated population (Dumont et al., 2012). The nurse’s role is not only to provide care to individuals as they leave the criminal justice system and re-enter the community, but also to educate police officers and justice staff in how to work with individuals entering the criminal system. The percentage of homeless persons with serious mental illness has been estimated to be more than 26%, and it is speculated that the lack of mental health agencies has led to a greater number of homeless young adults (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011). The challenge to psychiatric mental health nurses is in making contact with these individuals who are outside the system but desperately in need of treatment. Assessment of the biopsychosocial needs and capacities of patients living in the community requires expansion of the general psychiatric mental health nursing assessment (refer to Chapter 7). To be able to plan and implement effective treatment, the nurse must also develop a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s ability to cope with the demands of living in the community. • Housing adequacy and stability: If a patient faces daily fears of homelessness, it is not possible to focus on other treatment issues. • Income and source of income: A patient must have a basic income—whether from an entitlement, a relative, or other sources—to obtain necessary medication and meet daily needs for food and clothing. • Family and support system: The presence of a family member, friend, or neighbor supports the patient’s recovery and, with the patient’s consent, gives the nurse a contact person. • Substance abuse history and current use: Often hidden or minimized during hospitalization, substance abuse can be a destructive force, undermining medication effectiveness and interfering with community acceptance and procurement of housing. • Physical well-being: Factors that increase health risks and decrease life span for individuals with mental illnesses include decreased physical activity, smoking, medication side effects, and lack of routine health exams. Individual cultural characteristics are also very important to assess. For example, working with a patient who speaks a different language from the nurse requires the nurse to consider the implications of language and cultural background. The use of a translator or cultural consultant from the agency or from the family is essential when the nurse and patient speak different languages (refer to Chapter 5). Differences in characteristics, treatment outcomes, and interventions between inpatient and community settings are outlined in Table 4-1. Note that all of these interventions fall within the practice domain of the basic level registered nurse. TABLE 4-1 CHARACTERISTICS, TREATMENT OUTCOMES, AND INTERVENTIONS BY SETTING

Settings for psychiatric care

Continuum of psychiatric mental health care

Outpatient psychiatric mental health care

Primary care providers

Patient-centered medical homes

Community mental health centers

Psychiatric home care

Assertive community treatment

Other outpatient venues for psychiatric care

Prevention in community care

Outpatient and community psychiatric mental health care

Biopsychosocial assessment

Treatment goals and interventions

OUTPATIENT/COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH SETTING

INPATIENT SETTING

Characteristics

Intermittent supervision

24-hour supervision

Independent living environment with self-care, safety risks

Therapeutic milieu with hospital/staff supported healing environment

Treatment Outcomes

Stable or improved level of functioning in community

Stabilization of symptoms and return to community

Interventions

Establish long-term therapeutic relationship.

Develop short-term therapeutic relationship.

Develop comprehensive plan of care with patient and support system, with attention to sociocultural needs and maintenance of community living

Develop comprehensive plan of care, with attention to sociocultural needs of patient and focus on reintegration into the community

Encourage adherence with medication regimen.

Administer medication.

Teach and support adequate nutrition and self-care with referrals as needed.

Monitor nutrition and self-care with assistance as needed.

Assist patient in self-assessment, with referrals for health needs in community as needed.

Provide health assessment and intervention as needed.

Use creative strategies to refer patient to positive social activities.

Offer structured socialization activities.

Communicate regularly with family/support system to assess and improve level of functioning.

Plan for discharge with family/significant other with regard to housing and follow-up treatment. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree