Sensory Alterations

Objectives

• Differentiate among the processes of reception, perception, and reaction to sensory stimuli.

• Discuss the relationship of sensory function to an individual’s level of wellness.

• Discuss common causes and effects of sensory alterations.

• Discuss common sensory changes that normally occur with aging.

• Identify factors to assess in determining a patient’s sensory status.

• Identify nursing diagnoses relevant to patients with sensory alterations.

• Develop a plan of care for patients with sensory deficits.

• List interventions for preventing sensory deprivation and controlling sensory overload.

• Discuss ways to maintain a safe environment for patients with sensory deficits.

Key Terms

Aphasia, p. 1240

Auditory, p. 1233

Conductive hearing loss, p. 1245

Expressive aphasia, p. 1240

Gustatory, p. 1233

Hyperesthesia, p. 1246

Kinesthetic, p. 1233

Olfactory, p. 1233

Otolaryngologist, p. 1238

Ototoxic, p. 1241

Proprioceptive, p. 1236

Receptive aphasia, p. 1240

Refractive error, p. 1244

Sensory deficit, p. 1234

Sensory deprivation, p. 1234

Sensory overload, p. 1235

Stereognosis, p. 1233

Strabismus, p. 1244

Tactile, p. 1233

![]()

Imagine the world without sight, hearing, or the ability to feel objects or sense aromas around you. Human beings rely on a variety of sensory stimuli to give meaning and order to events occurring in their environment. The senses form the perceptual base of our world. Stimulation comes from many sources in and outside the body, particularly through the senses of sight (visual), hearing (auditory), touch (tactile), smell (olfactory), and taste (gustatory). The body also has a kinesthetic sense that enables a person to be aware of the position and movement of body parts without seeing them. Stereognosis is a sense that allows a person to recognize the size, shape, and texture of an object. The ability to speak is not a sense but it is similar in that some patients lose the ability to interact meaningfully with other human beings. Meaningful stimuli allow a person to learn about the environment and are necessary for healthy functioning and normal development. When sensory function is altered, a person’s ability to relate to and function within the environment changes drastically.

Many patients seeking health care have preexisting sensory alterations. Others develop them as a result of medical treatment (e.g., hearing loss from antibiotic use or hearing or visual loss from brain tumor removal) or hospitalization. The health care environment is a place of unfamiliar sights, sounds, and smells and minimal contact with family and friends. If patients feel depersonalized and are unable to receive meaningful stimuli, serious sensory alterations sometimes develop.

As a nurse, you meet the needs of patients with existing sensory alterations and recognize patients most at risk for developing sensory problems. You also help patients who have partial or complete loss of a major sense to find alternate ways to function safely within their environment.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Normal Sensation

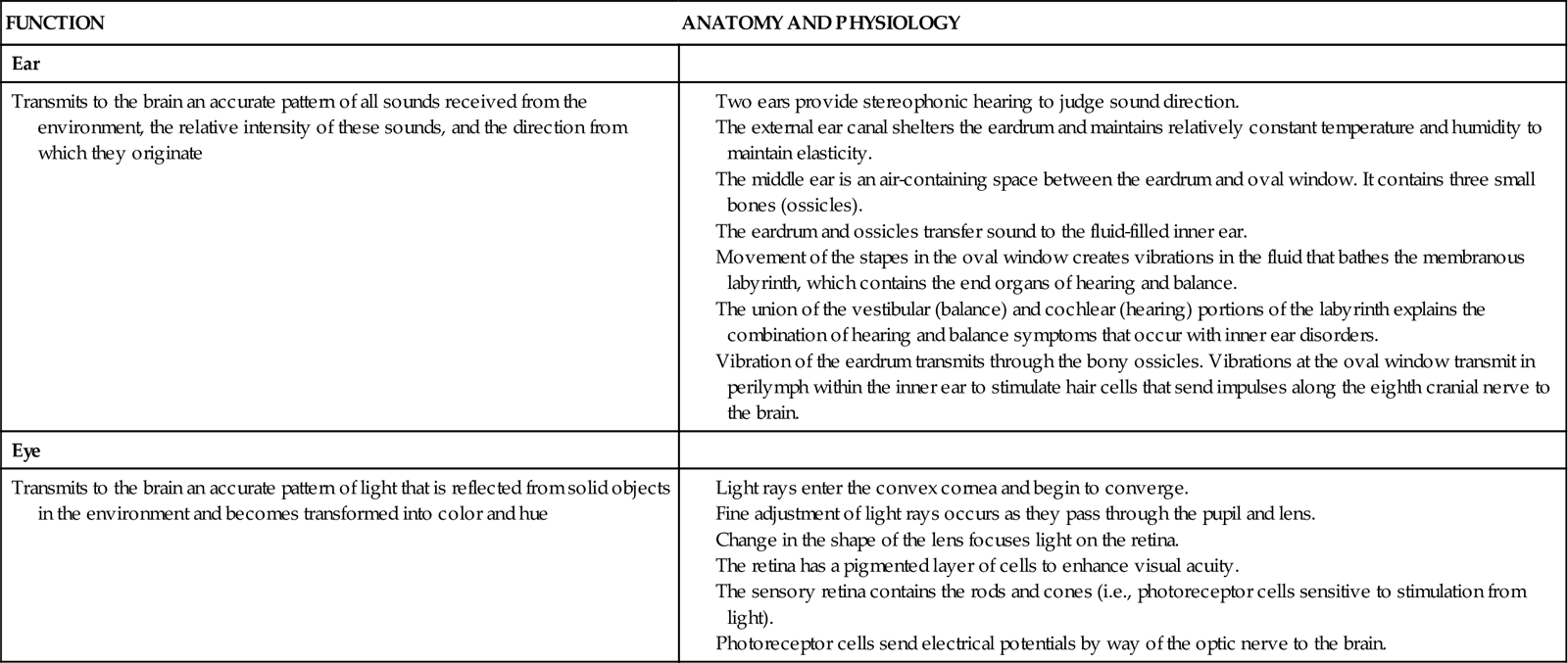

Normally the nervous system continually receives thousands of bits of information from sensory nerve organs, relays the information through appropriate channels, and integrates the information into a meaningful response. Sensory stimuli reach the sensory organs to elicit an immediate reaction or present information to the brain to be stored for future use. The nervous system must be intact for sensory stimuli to reach appropriate brain centers and for an individual to perceive the sensation. After interpreting the significance of a sensation, the person is then able to react to the stimulus. Table 49-1 summarizes normal hearing and vision.

TABLE 49-1

Reception, perception, and reaction are the three components of any sensory experience (see Chapter 43). Reception begins with stimulation of a nerve cell called a receptor, which is usually for only one type of stimulus such as light, touch, or sound. In the case of special senses, the receptors are grouped close together or located in specialized organs such as the taste buds of the tongue or the retina of the eye. When a nerve impulse is created, it travels along pathways to the spinal cord or directly to the brain. For example, sound waves stimulate hair cell receptors within the organ of Corti in the ear, which causes impulses to travel along the eighth cranial nerve to the acoustic area of the temporal lobe. Sensory nerve pathways usually cross over to send stimuli to opposite sides of the brain.

The actual perception or awareness of unique sensations depends on the receiving region of the cerebral cortex, where specialized brain cells interpret the quality and nature of sensory stimuli. When a person becomes conscious of a stimulus and receives the information, perception takes place. Perception includes integration and interpretation of stimuli based on the person’s experiences. A person’s level of consciousness influences perception and interpretation of stimuli. Any factors lowering consciousness impair sensory perception. If sensation is incomplete such as blurred vision or if past experience is inadequate for understanding stimuli such as pain, the person can react inappropriately to the sensory stimulus.

It is impossible to react to all stimuli entering the nervous system. The brain prevents sensory bombardment by discarding or storing sensory information. A person usually reacts to stimuli that are most meaningful or significant at the time. However, after continued reception of the same stimulus, a person stops responding, and the sensory experience goes unnoticed. For example, a person concentrating on reading a good book is not aware of background music. This adaptability phenomenon occurs with most sensory stimuli except for those of pain.

The balance between sensory stimuli entering the brain and those actually reaching a person’s conscious awareness maintains a person’s well-being. If an individual attempts to react to every stimulus within the environment or if the variety and quality of stimuli are insufficient, sensory alterations occur.

Sensory Alterations

The most common types of sensory alterations are sensory deficits, sensory deprivation, and sensory overload. When a patient suffers from more than one sensory alteration, the ability to function and relate effectively within the environment is seriously impaired.

Sensory Deficits

A deficit in the normal function of sensory reception and perception is a sensory deficit. A person loses a sense of self with impaired senses. Initially he or she withdraws by avoiding communication or socialization with others in an attempt to cope with the sensory loss. It becomes difficult for the person to interact safely with the environment until he or she learns new skills. When a deficit develops gradually or when considerable time has passed since the onset of an acute sensory loss, a person learns to rely on unaffected senses. Some senses may even become more acute to compensate for an alteration. For example, a blind patient develops an acute sense of hearing to compensate for visual loss.

Patients with sensory deficits often change behavior in adaptive or maladaptive ways. For example, a patient with a hearing impairment turns the unaffected ear toward the speaker to hear better, whereas another patient avoids people because he or she is embarrassed about not being able to understand what other people say. Box 49-1 summarizes common sensory deficits and their influence on those affected.

Sensory Deprivation

The reticular activating system in the brainstem mediates all sensory stimuli to the cerebral cortex; thus patients are able to receive stimuli even while sleeping deeply. Sensory stimulation must be of sufficient quality and quantity to maintain a person’s awareness. Three types of sensory deprivation are reduced sensory input (sensory deficit from visual or hearing loss), the elimination of patterns or meaning from input (e.g., exposure to strange environments), and restrictive environments (e.g., bed rest) that produce monotony and boredom (Ebersole et al., 2008).

There are many effects of sensory deprivation (Box 49-2). In adults the symptoms are similar to psychological illness, confusion, symptoms of severe electrolyte imbalance, or the influence of psychotropic drugs. Therefore always be aware of a patient’s existing sensory function and the quality of stimuli within the environment.

Sensory Overload

When a person receives multiple sensory stimuli and cannot perceptually disregard or selectively ignore some stimuli, sensory overload occurs. Excessive sensory stimulation prevents the brain from responding appropriately to or ignoring certain stimuli. Because of the multitude of stimuli leading to overload, a person no longer perceives the environment in a way that makes sense. Overload prevents meaningful response by the brain; the patient’s thoughts race, attention scatters in many directions, and anxiety and restlessness occur. As a result, overload causes a state similar to that produced by sensory deprivation. However, in contrast to deprivation, overload is individualized. The amount of stimuli necessary for healthy function varies with each individual. People are often subject to environmental overload more at one time than another. A person’s tolerance to sensory overload varies with level of fatigue, attitude, and emotional and physical well-being.

The acutely ill patient easily experiences sensory overload. The patient in constant pain or who undergoes frequent monitoring of vital signs is at risk. Multiple stimuli combine to cause overload even if the nurse offers a comforting word or provides a gentle back rub. Some patients do not benefit from nursing intervention because their attention and energy are focused on more stressful stimuli. Another example is a patient who is hospitalized in an intensive care unit (ICU), where the activity is constant. Lights are always on. Patients can hear sounds from monitoring equipment, staff conversations, equipment alarms, and the activities of people entering the unit. Even at night an ICU is very noisy.

It is easy to confuse the behavioral changes associated with sensory overload with mood swings or simple disorientation. Look for symptoms such as racing thoughts, scattered attention, restlessness, and anxiety. Patients in ICUs sometimes resort to constantly fingering tubes and dressings. Constant reorientation and control of excessive stimuli become an important part of a patient’s care.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Factors Influencing Sensory Function

Many factors influence the capacity to receive or perceive stimuli. All are conditions or situations that you manage when delivering care.

Age

Infants and children are at risk for visual and hearing impairment because of a number of genetic, prenatal, and postnatal conditions. A concern with high-risk neonates is that early, intense visual and auditory stimulation can adversely affect visual and auditory pathways and alter the developmental course of other sensory organs (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Visual changes during adulthood include presbyopia and the need for glasses for reading. These changes usually occur from ages 40 to 50. In addition, the cornea, which assists with light refraction to the retina, becomes flatter and thicker. These aging changes lead to astigmatism. Pigment is lost from the iris, and collagen fibers build up in the anterior chamber, which increases the risk of glaucoma by decreasing the resorption of intraocular fluid. Other normal visual changes associated with aging include reduced visual fields, increased glare sensitivity, impaired night vision, reduced depth perception, and reduced color discrimination.

Hearing changes begin at the age of 30. Changes associated with aging include decreased hearing acuity, speech intelligibility, and pitch discrimination. Low-pitched sounds are easiest to hear, but it is difficult to hear conversation over background noise. It is also difficult to discriminate the consonants (z, t, f, g) and high-frequency sounds (s, sh, ph, k). Vowels that have a low pitch are easiest to hear. Speech sounds are distorted, and there is a delayed reception and reaction to speech. A concern with normal age-related sensory changes is that older adults with a deficit are sometimes inappropriately diagnosed with dementia (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Gustatory and olfactory changes begin around age 50 and include a decrease in the number of taste buds and sensory cells in the nasal lining. Reduced taste discrimination and sensitivity to odors are common.

Proprioceptive changes common after age 60 include increased difficulty with balance, spatial orientation, and coordination. Older adults cannot avoid obstacles as quickly, and the automatic response to protect and brace oneself when falling is slower. Older adults experience tactile changes, including declining sensitivity to pain, pressure, and temperature secondary to peripheral vascular disease and neuropathies.

Meaningful Stimuli

Meaningful stimuli reduce the incidence of sensory deprivation. In the home meaningful stimuli include pets, music, television, pictures of family members, and a calendar and clock. The same stimuli need to be present in health care settings. Note whether patients have roommates or visitors. The presence of others offers positive stimulation. However, a roommate who constantly watches television, persistently tries to talk, or continuously keeps lights on contributes to sensory overload. The presence or absence of meaningful stimuli influences alertness and the ability to participate in care.

Amount of Stimuli

Excessive stimuli in an environment causes sensory overload. The frequency of observations and procedures performed in an acute health care setting are often stressful. If a patient is in pain or restricted by a cast or traction, overstimulation frequently is a problem. In addition, a room that is near repetitive or loud noises (e.g., an elevator, stairwell, or nurses’ station) contributes to sensory overload.

Social Interaction

The amount and quality of social contact with supportive family members and significant others influence sensory function. The absence of visitors during hospitalization or residency in an extended care facility influences the degree of isolation a patient feels. This is a common problem in hospital intensive care settings, where visitation is often restricted. The ability to discuss concerns with loved ones is an important coping mechanism for most people. Therefore the absence of meaningful conversation results in feelings of isolation, loneliness, anxiety, and depression for a patient. Often this is not apparent until behavioral changes occur.

Environmental Factors

A person’s occupation places him or her at risk for hearing, visual, and peripheral nerve alterations. Individuals who have occupations involving exposure to high noise levels (e.g., factory or airport workers) are at risk for noise-induced hearing loss and need to be screened for hearing impairments. Hazardous noise is common in work settings and recreational activities. Noisy recreational activities that weaken hearing ability include target shooting and hunting, woodworking, and listening to loud music. Individuals who have occupations involving risk of exposure to chemicals or flying objects (e.g., welders) are at risk for eye injuries and need to be screened for visual impairments. Sports activities and consumer fireworks also place individuals at risk for visual alterations. Occupations that involve repetitive wrist or finger movements (e.g., heavy assembly line work) cause pressure on the median nerve, resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome. Carpal tunnel syndrome alters tactile sensation and is one of the most common industrial or work-related injuries. Patients at risk for carpal tunnel need to be carefully assessed for numbness, tingling, weakness, and pain.

A hospitalized patient is sometimes at risk for sensory alterations as a result of exposure to environmental stimuli or a change in sensory input. Patients who are immobilized by bed rest or who have a chronic disability are unable to experience all of the normal sensations of free movement. Another group at risk includes patients isolated in a health care setting or at home because of conditions such as active tuberculosis (see Chapter 28). These patients stay in private rooms and are often unable to enjoy normal interactions with visitors.

Cultural Factors

Certain sensory alterations occur more commonly in select ethnic groups. Analysis of data from the African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation study (ADAGES) showed that people of African ethnicity perform significantly worse than people of European descent on tests of visual function (Racette et al., 2010). Cultural disparities in vision impairment are significant, in part because visual impairment may be indirectly associated with an increased risk of suicide through poor self-rated health (Lam et al., 2008). Box 49-3 summarizes additional sensory alterations that are associated with a patient’s cultural heritage.

Critical Thinking

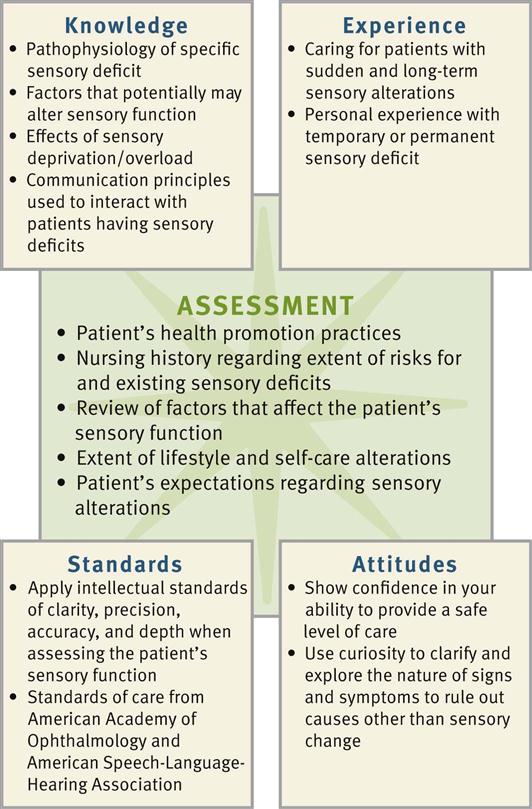

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge and information gathered from patients, experience, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the information necessary, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. Patients’ conditions are always changing. During assessment (Fig. 49-1) consider all critical thinking elements that help you make appropriate nursing diagnoses. In the case of sensory alterations, integrate knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensory deficits, factors that affect sensory function, and therapeutic communication principles. This knowledge enables you to conduct appropriate assessments, anticipate what to recognize when a patient describes a sensory problem, and make judgments of any abnormalities. For example, knowing the typical symptoms caused by a cataract helps you recognize the pattern of visual changes that a patient with cataracts reports.

Previous experiences in caring for patients with sensory deficits enable nurses to recognize limitations in function in each new patient and how they affect the patient’s ability to carry out daily activities. For example, after caring for a patient with a hearing impairment, you are able to conduct a more effective assessment of the next patient by using approaches that promote the patient’s ability to hear your questions.

When critical thinking attitudes and standards are applied during assessment, they ensure a thorough and accurate database from which to make decisions. For example, perseverance is necessary to learn details about how visual changes influence a patient’s ability to socialize. Evidence-based standards of care and practice such as those from the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association provide criteria for screening sensory problems and establishing standards for competent, safe, effective care and practice. Use critical thinking to conduct a thorough assessment and then plan, implement, and evaluate care that enables the patient to function safely and effectively (Box 49-4).

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care for your patients.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

When conducting an assessment, value the patient as a full partner in planning, implementing, and evaluating care. Patients are often hesitant to admit sensory losses. Therefore start gathering information by establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient. Elicit his or her values, preferences, and expectations with regard to his or her sensory impairment. Many patients have a definite plan as to how they want their care delivered. Some patients expect caregivers to recognize and appropriately manage and adjust their environment to meet their sensory needs. This includes helping the patient learn and adapt to a changed lifestyle based on the specific sensory impairment. Determine from the patient which interventions have been helpful in the past in the management of limitations. Assess the patient’s expertise with his or her own health and symptoms. Always remember that patients with sensory alterations have strengthened their other senses and expect caregivers to anticipate their needs (e.g., for safety and security).

When assessing a patient with or at risk for sensory alteration, first consider the pathophysiology of existing deficits and the factors influencing sensory function to anticipate how to approach his or her assessment. For example, if a patient has a hearing disorder, adjust your communication style and focus the assessment on relevant criteria related to hearing deficits. Collect a history that also assesses the patient’s current sensory status and the degree to which a sensory deficit affects the patient’s lifestyle, psychosocial adjustment, developmental status, self-care ability, health promotion habits, and safety. Also focus the assessment on the quality and quantity of stimuli within the patient’s environment.

Persons at Risk

Older adults are a high-risk group because of normal physiological changes involving sensory organs. However, be careful not to automatically assume that a patient’s sensory problem is related to advancing age. For example, adult sensorineural hearing loss is often caused by exposure to excess and prolonged noise or metabolic, vascular, and other systemic alterations. Some patients benefit from a referral to an audiologist or otolaryngologist if assessment reveals serious hearing problems.

Other individuals at risk for sensory alterations include those living in a confined environment such as a nursing home. Although most quality nursing homes or centers offer meaningful stimulation through group activities, environmental design, and mealtime gatherings, there are exceptions. The individual who is confined to a wheelchair, suffers from poor hearing and/or vision, has decreased energy, and avoids contact with others is at significant risk for sensory deprivation. If the environment creates monotony, the individual is less able to learn and think. Patients who are acutely ill are also at risk because of an unfamiliar and unresponsive environment. This does not mean that all hospitalized patients have sensory alterations. However, you need to carefully assess patients subjected to continued sensory stimulation (e.g., ICU settings, long-term hospitalization, or multiple therapies). Assess the patient’s environment within both the health care setting and the home, looking for factors that pose risks or need adjustment to provide safety and more stimulation.

Sensory Alterations History

The nursing history includes assessment of the nature and characteristics of sensory alterations or any problem related to an alteration (Box 49-5). When taking the history, consider the ethnic or cultural background of the patient because certain alterations are higher in some cultural groups.

During the history it is useful to assess the patient’s self-rating for a sensory deficit by asking, “Rate your hearing as excellent, good, fair, poor, or bad.” Then, based on the patient’s self-rating, explore his or her perception of a sensory loss more fully. This provides an in-depth look at how the sensory loss influences the patient’s quality of life. In the case of hearing problems, a screening tool such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE-S) effectively identifies patients needing audiological intervention. The HHIE-S is a 5-minute, 10-item questionnaire that assesses how the individual perceives the social and emotional effects of hearing loss. The higher the HHIE-S score, the greater the handicapping effect of a hearing impairment.

A nursing history also reveals any recent changes in a patient’s behavior. Frequently friends or family are the best resources for this information. Ask the family the following questions:

Mental Status

Assessment of mental status is valuable when you suspect sensory deprivation or overload. Observation of a patient during history taking, during the physical examination (see Chapter 30), and while providing nursing care offers valuable data about key patient behaviors and his or her mental status. Observe the patient’s physical appearance and behavior, measure cognitive ability, and assess his or her emotional status. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a tool you can use to measure disorientation, change in problem-solving abilities, and altered conceptualization and abstract thinking (see Chapter 30). For example, a patient with severe sensory deprivation is not always able to carry on a conversation, remain attentive, or display recent or past memory. An important step toward preventing cognition-related disability is education by nurses about disease process, available services, and assistive devices.

Physical Assessment

To identify sensory deficits and their severity, use physical assessment techniques to assess vision, hearing, olfaction, taste, and the ability to discriminate light touch, temperature, pain, and position (see Chapter 30). Table 49-2 summarizes specific assessment techniques for identifying sensory deficits. You gather more accurate data if the examination room is private, quiet, and comfortable for the patient. In addition, rely on personal observation to detect sensory alterations. Patients with a hearing impairment may seem inattentive to others, respond with inappropriate anger when spoken to, believe people are talking about them, answer questions inappropriately, have trouble following clear directions, and have monotonous voice quality and speak unusually loud or soft.

TABLE 49-2

Assessment of Sensory Function

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | BEHAVIOR INDICATING DEFICIT (CHILDREN) | BEHAVIOR INDICATING DEFICIT (ADULTS) |

| Vision | ||

| Self-stimulation, including eye rubbing, body rocking, sniffing or smelling, arm twirling; hitching (using legs to propel while in sitting position) instead of crawling | Poor coordination, squinting, underreaching or overreaching for objects, persistent repositioning of objects, impaired night vision, accidental falls | |

| Hearing | ||

Assess patient’s hearing acuity (see Chapter 30) using spoken word and tuning fork tests. Assess for history of tinnitus. Observe patient conversing with others. Inspect ear canal for hardened cerumen. Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|