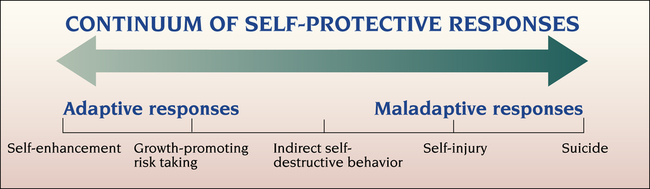

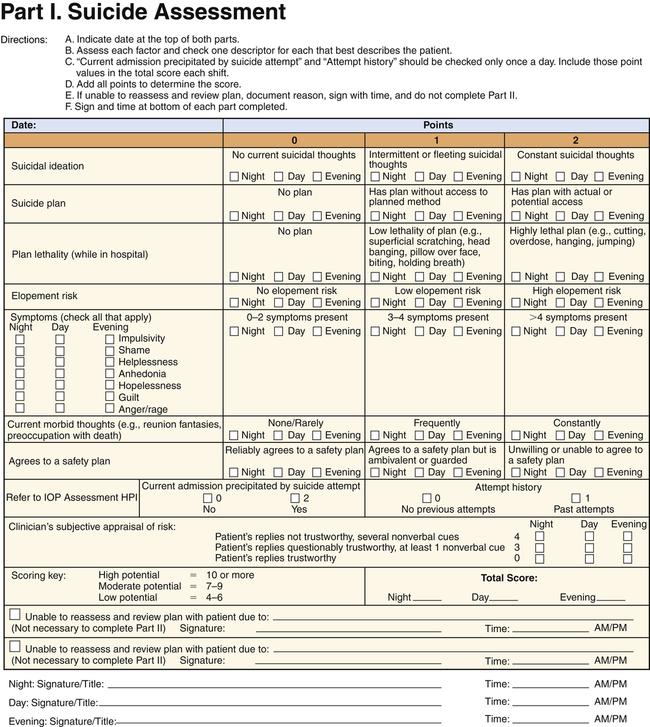

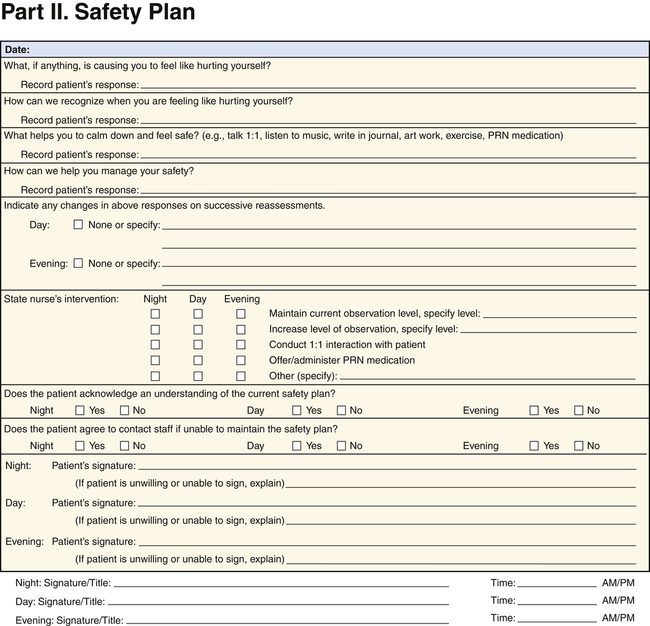

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, 1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive self-protective responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with self-protective responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to self-protective responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to self-protective responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to self-protective responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to self-protective responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to self-protective responses. 8. Develop a patient education plan to promote compliance with health care treatment. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to self-protective responses. 10. Evaluate nursing care related to self-protective responses. behavior, self-injury, and suicide are maladaptive responses. Self-destructive behavior may be direct or indirect. • Direct self-destructive behavior includes any form of suicidal activity, such as suicide ideation, threats, attempts, and completed suicide. The intent of this behavior is death, and the person is aware of the desired outcome. • Indirect self-destructive behavior is any activity that is harmful to the person’s physical well-being and potentially may result in death. The person may be unaware of this potential and may deny it if confronted. Examples include eating disorders, abuse of alcohol and drugs, cigarette smoking, reckless driving, gambling, criminal activity, sexual promiscuity, socially deviant behavior, participation in high-risk sports, and noncompliance with medical treatment. Theories of self-destructive behavior overlap with those of self-concept (see Chapter 17) and disturbances in mood (see Chapter 18). To think about or attempt destruction of the self, the person must have low self-regard. Low self-esteem leads to depression, which is always present in self-destructive behavior. The range of self-protective responses is shown in Figure 19-1. Worldwide, at least 1000 suicides occur each day. Suicide is the leading cause of death, outnumbering homicide or war-related deaths. Most people with suicide ideation, plans, and attempts receive no treatment (Bruffaerts et al, 2011). In the United States more than 36,000 people complete the act of suicide each year, an average of one person every 15 minutes. In 2008, 8.3 million adults reported having suicidal thoughts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death, outnumbering homicide, which is the fifteenth leading cause of death in the United States (American Association of Suicidology, 2011). The actual number of suicides may be two to three times higher because of underreporting. In addition, many single-car accidents and homicides are, in fact, suicides. Additional statistics regarding suicide in the United States include the following: • The highest suicide rate for any group in the United States is among people older than age 80 years. Elderly adults have a rate of suicide almost 50% higher than that of the nation as a whole (all ages). • Suicide is the third leading killer of young people. The rate of suicide among youth has tripled in the past 30 years. Teen suicide in the United States is almost five times as common among boys as among girls. Reports of suicide among young children are rare, but suicidal behavior is not. As many as 12,000 children ages 5 to 14 years are hospitalized in the United States every year for deliberate self-destructive acts. • The incidence of suicide varies among cultural groups (Box 19-1). Suicide is more common among whites than African Americans at all ages. • Males commit the overwhelming majority of completed suicides; women attempt suicide three times more often then men. • Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death for women between the ages of 15 and 44 years, exceeding deaths due to homicide, cerebrovascular disease, or diabetes (LaVonne and Karch, 2010). • Guns account for half of all completed suicides (Ilgen et al, 2008). Women tend to use potentially less lethal means, such as medications and wrist slashing. One third of all women and more than half of those 15 to 29 years of age who complete suicide use guns. • People with mental retardation. The mentally retarded may have outward-directed aggression along with self-injurious behavior. • Psychotic patients. Self-injuring acts among psychotic patients tend to be sporadic and often occur in response to command hallucinations or delusions. • Prison populations. Self-injury in prisons is difficult to assess because of poor documentation, drug use, and undiagnosed psychiatric disorders. Many self-injurious events among prisoners may be intentionally manipulative, designed to force transfer to a less restrictive facility. • Character disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder. These patients are often young and female and have a poor tolerance of anxiety and anger; also included are patients with eating disorders. • “Will you remember me when I’m gone?” • “Take care of my family for me.” • “I won’t be in your way much longer.” • “There’s nothing more that I can do.” also includes whether the person has made a specific plan and whether the means to carry out the plan are available. The most suicidal person is one who has all of the following: • A highly lethal method (e.g., a gunshot to the head) • A specific plan (e.g., as soon as one’s spouse goes shopping) • The means readily available (e.g., a loaded gun in a desk drawer) Research done on completed suicide has of necessity been retrospective. However, it can be informative to interview survivors. This procedure is known as the psychological autopsy (Innamorati et al, 2008). It is a retrospective review of the person’s behavior before the suicide. Table 19-1 compares the characteristics of suicide completers and suicide attempters based on this process. TABLE 19-1 CHARACTERISTICS OF SUICIDE COMPLETERS AND ATTEMPTERS When suicide is successful, the survivors are left with many feelings that they cannot communicate to the involved object, the dead person (Box 19-2). This may lead to an unresolved grief reaction, depression, social stigma, and suicidal ideation. Some suicide prevention centers have become involved in postvention, in which survivors are helped, either individually or in groups, to express their feelings and work through their grief. In summary, the suicidal patient may have many different clinical behaviors. Mood disturbances are often present, as are somatic complaints. Feelings of hopelessness and helplessness are important in explaining suicidal ideation. Nurses should take a careful medical and psychiatric history, paying specific attention to the mental status examination (described in Chapter 6) and the psychosocial history, and should evaluate the patient for recent losses, life stresses, and substance use and abuse. Most people who commit suicide have visited a primary care provider, emergency department (ED), or psychiatric outpatient service in the weeks before their death. Errors in recognition and inadequate assessment likely contribute to a number of these deaths. Adequate screening, protection of the patient, and acceptable treatment could prevent these occurrences (Reid, 2010). Suicidal patients often present initially in the ED. About 666,000 people visited EDs for nonfatal, self-inflicted injuries in 2008 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). As many as 1 in 10 people who end their lives by suicide are seen in the ED within 2 months of dying, but many of them are never assessed for suicide risk (Pompili et al, 2011). Psychiatric evaluation of suicide attempters in the ED should include the use of a standardized tool to evaluate suicide ideation and suicide risk (Pompili et al, 2009). After completing the assessment, the nurse should document the following (Scott and Resnick, 2009): • That a suicide risk assessment was conducted • Risk factors found to be present • Interventions taken to address the risk factors • Level of risk determined (minimal, moderate, or high) Directly questioning the patient about suicidal thoughts and plans will not cause the patient to take suicidal action. Rather, most people want to be prevented from carrying out their self-destruction. Most patients are relieved to be asked about these feelings (Crawford et al, 2011). In asking about suicide, nurses can begin with general questions, such as the following: • “Have you ever felt that life was not worth living?” • “Did you ever wish that one morning you would just not wake up?” These can be followed by more specific questions, such as If the patient has had thoughts of death, self-harm, or suicide, the nurse must then ask more focused and direct questions about the method, plan, and means. A tool used in one inpatient setting is presented in Figure 19-2. Other suicide assessment tools also are available (Young and Erwin, 2008; Hermes et al, 2009). Childhood trauma and a history of abuse or incest also may precipitate self-destructiveness if negative perceptions have been internalized (Bruffaerts et al, 2010). Other predisposing factors related to self-destructive behavior include the inability to communicate needs and feelings verbally; feelings of guilt, depression, and depersonalization; and fluctuating emotions. Suicide is the most serious complication of mood disorders; 15% of individuals with these illnesses end their lives by suicide. The time spent depressed is a major risk factor determining overall long-term risk (Holma et al, 2010). Suicide is particularly common among depressed elderly men. Patients with bipolar disorder and psychotic depression are at greatest risk. Many who die from suicide have a prior history of attempts, have explicitly communicated their intent, and have been in psychiatric treatment during the months before their death. Anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, are associated with increased rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide. Other disorders that are associated with high risk include eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, some personality disorders (borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder), and conduct disorders in adolescents (Berk et al, 2009).

Self-Protective Responses and Suicidal Behavior

Continuum of Self-Protective Responses

Epidemiology of Suicide

Assessment

Behaviors

Noncompliance/Nonadherence

Self-Injury

Suicidal Behavior

SUICIDE COMPLETERS

SUICIDE ATTEMPTERS

Three times as likely to be men

Mainly women younger than 40 years of age

Usually have depression and/or alcohol or substance abuse

Less likely to have depression and other psychiatric conditions; more likely to have personality disorders

Plan the suicide act

Act impulsively

Use highly lethal method

Use method with low lethality

Select a setting where they are unlikely to be interrupted

Act in the presence of or notify others

Nature of the Assessment

Predisposing Factors

Psychiatric Diagnosis

Self-Protective Responses and Suicidal Behavior

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access