Self-Concept

Objectives

• Discuss factors that influence the components of self-concept.

• Identify stressors that affect self-concept and self-esteem.

• Examine cultural considerations that affect self-concept.

• Apply the nursing process to promote a patient’s self-concept.

Key Terms

Body image, p. 658

Identity, p. 660

Identity confusion, p. 662

Role ambiguity, p. 663

Role conflict, p. 663

Role overload, p. 663

Role performance, p. 661

Role strain, p. 663

Self-concept, p. 658

Self-esteem, p. 661

Sick role, p. 663

![]()

Self-concept is an individual’s view of self. It is a subjective view and a complex mixture of unconscious and conscious thoughts, attitudes, and perceptions. Self-concept, or how a person thinks about oneself, directly affects self-esteem, or how one feels about oneself. Although these two terms are often used interchangeably, nurses need to differentiate the two so they correctly and completely assess patients and develop an individualized plan of care based on the patient’s needs.

Nurses care for patients who face a variety of health problems that threaten their self-concept and self-esteem. The loss of bodily function, decline in activity tolerance, and difficulty in managing a chronic illness are examples of situations that change a patient’s self-concept. As a nurse, you will help patients adjust to alterations in self-concept and support components of self-concept to promote successful coping and positive health outcomes.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The development and maintenance of self-concept and self-esteem begin at a young age and continue across the life span with a general tendency for boys to report higher self-esteem than girls. However, the exact amount of this gender difference and the way it varies across the life span remain unclear. Parents and other primary caregivers influence the development of a child’s self-concept and self-esteem. In addition, individuals learn and internalize cultural influences on self-concept and self-esteem in childhood and adolescence (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). There is a significant amount of emphasis on fostering a school-age child’s self-concept. In general, young children tend to rate themselves higher than they rate other children, suggesting that their view of themselves is positively inflated. Adolescence is a particularly critical time when many variables, including school, family, and friends, affect self-concept and self-esteem (Martyn-Nemeth et al., 2009). The adolescent experience can adversely affect self-esteem, often more strongly for girls than for boys. For example, some adolescent girls are more sensitive about their appearance and how others view them. Thus it is important to assess changes in self-esteem among early, middle, and late adolescence because changes in self-concept occur over time (Fig. 33-1).

Job satisfaction and overall performance in adulthood are also linked to self-esteem. Sometimes when individuals lose a job, their sense of self diminishes, they lose motivation to be socially active, or they even become depressed. They lose their job identity, and this alters their self-perceptions. Establishing a stable sense of self that transcends relationships and situations is a developmental goal of adulthood.

Evidence suggests that sense of self is often negatively affected in older adulthood because of the intensity of emotional and physical changes associated with aging (Ebersole et al., 2008; Price, 2010). For example, when an older adult loses a partner or experiences a change in health, sometimes there is a change in social interaction or even self-care practices.

Researchers also found ethnic and cultural differences in self-concept and self-esteem across the life span that impact health behaviors. In Latino youth, ethnic pride and self-esteem serve as protective factors against risk behaviors, including intentions to smoke cigarettes and to have sexual intercourse (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). Cultural identity of older adults is one of the major elements of self-concept and a key aspect of self-esteem (Ebersole et al., 2008). Considering aging from a cultural perspective provides the context for providing the highest-quality nursing care. Sensitivity to factors that affect self-concept and self-esteem in diverse cultures is essential to ensure an individualized approach to health care.

How individuals view themselves and their perception of their health are closely related. Lower self-esteem is a risk factor that leaves one vulnerable to health problems, whereas higher self-esteem and strong social relationships support good health (Stinson et al., 2008). A patient’s belief in personal health often enhances his or her self-concept. Statements such as “I can get through anything” or “I’ve never been sick a day in my life” indicate that a person’s thoughts about personal health are positive. Illness, hospitalization, and surgery also affect self-concept. Chronic illness often affects the ability to provide financial support and maintain relationships, which then affects an individual’s self-esteem and perceived roles within the family. Negative perceptions regarding health status are reflected in such statements as “It’s not worth it anymore” or “I’m a burden to my family.” Further, chronic illness affects identity and body image as reflected by verbalizations such as “I’ll never get any better” or “I can’t stand to look at myself anymore.”

What individuals think and how they feel about themselves affect the way in which they care for themselves physically and emotionally and how they care for others. Further, a person’s behaviors are generally consistent with both self-concept and self-esteem. Individuals who have a poor self-concept often do not feel in control of situations and worthy of care, which influences decisions regarding health care. Patients often have difficulty making even simple decisions, such as what to eat. Knowledge of variables that affect self-concept and self-esteem is critical to provide effective treatment.

Nursing Knowledge Base

In providing evidence-based practice to patients, incorporate professional nursing knowledge developed from the humanities, sciences, nursing research, and clinical practice. A broad knowledge base allows nurses to have a holistic view of patients, thus promoting quality patient care that best meets the self-concept needs of each patient and family. Understanding a patient’s self-concept is a necessary part of all nursing care (Stuart, 2009).

Development of Self-Concept

The development of self-concept is a complex lifelong process that involves many factors. Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development (1963) remains beneficial in understanding key tasks that individuals face at various stages of development. Each stage builds on the tasks of the previous stage. Successful mastery of each stage leads to a solid sense of self (Box 33-1).

Learn to recognize an individual’s failure to achieve an age-appropriate developmental stage or his or her regression to an earlier stage in a period of crisis. This understanding allows you to individualize care and determine appropriate nursing interventions. Self-concept is always changing and is based on the following:

• Perceived reactions of others to one’s body

• Ongoing perceptions and interpretations of the thoughts and feelings of others

• Personal and professional relationships

• Academic and employment-related identity

• Personality characteristics that affect self-expectations

• Perceptions of events that have an impact on the self

• Mastery of prior and new experiences

Self-esteem is usually highest in childhood, declines during adolescence, gradually rises throughout adulthood, and diminishes again in old age (Stuart, 2009). Although this pattern varies, in general it holds true across gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. Children often report high self-esteem because their sense of self is inflated by a variety of extremely positive sources, and the subsequent decline is from time to time associated with a shift to more realistic information about the self.

Erikson’s (1963) emphasis on the generativity stage (see Chapter 11) explains the rise in self-esteem and self-concept in adulthood. The individual focuses on being increasingly productive and creative at work, while at the same time promoting and guiding the next generation. Several individuals report a decline in self-esteem in later adulthood (Ebersole et al., 2008). Based on Erikson’s stages of development, a decline in self-concept in later adulthood reflects a diminished need for self-promotion and a shift in self-concept to a more modest and balanced view of self. Identifying specific nursing interventions to address the unique needs of patients at various life stages is essential.

Components and Interrelated Terms of Self-Concept

A positive self-concept gives a sense of meaning, wholeness, and consistency to a person. A healthy self-concept has a high degree of stability, which generates positive feelings toward self. The components of self-concept are identity, body image, and role performance. Because how one thinks about oneself (self-concept) affects how one feels about oneself (self-esteem), both concepts need to be evaluated.

Identity

Identity involves the internal sense of individuality, wholeness, and consistency of a person over time and in different situations. It implies being distinct and separate from others. Being “oneself” or living an authentic life is the basis of true identity. Children learn culturally accepted values, behaviors, and roles through identification and modeling. They often gain an identity from self-observations and from what individuals tell them. An individual first identifies with parenting figures and later with other role models such as teachers or peers. To form an identity, the child must be able to bring together learned behaviors and expectations into a coherent, consistent, and unique whole (Erikson, 1963).

The achievement of identity is necessary for intimate relationships because individuals express identity in relationships with others (Stuart, 2009). Sexuality is a part of identity, and its focus differs across the life span. For example, as an adult ages, the focus shifts from procreation to companionship, physical and emotional intimacy, and pleasure-seeking (Ebersole et al., 2008). Gender identity is a person’s private view of maleness or femaleness; gender role is the masculine or feminine behavior exhibited. This image and its meaning depend on culturally determined values (see Chapters 9 and 22).

Cultural differences in identity exist (Box 33-2). Racial or cultural identity develops from identification and socialization within an established group and through the experience of integrating the response of individuals outside the cultural or racial group into one’s self-concept. Differences in ethnic identity (e.g., Mexican American or Cuban American) exist through identification with traditions, customs, and rituals within one’s race/ethnic group (e.g., Hispanic/Latino). In general, the more a person identifies with social groups, the greater his or her self-esteem. In addition, when ethnic identity is central to self-concept and is positive, ethnic pride and self-esteem tend to be high (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). An individual who experiences discrimination, prejudice, or environmental stressors such as low-income or high-crime neighborhoods often conceptualizes himself or herself differently than an individual who experiences better living conditions.

Body Image

Body image involves attitudes related to the body, including physical appearance, structure, or function. Feelings about body image include those related to sexuality, femininity and masculinity, youthfulness, health, and strength. These mental images are not always consistent with a person’s actual physical structure or appearance. Some body image distortions have deep psychological origins, such as the eating disorder anorexia nervosa. Other alterations occur as a result of situational events, such as the loss or change in a body part. Be aware that most men and women experience some degree of dissatisfaction with their bodies, which affects body image and overall self-concept. Individuals often exaggerate disturbances in body image when a change in health status occurs. The way others view a person’s body and the feedback offered are also influential. For example, a controlling, violent husband tells his wife that she is ugly and that no one else would want her. Over the years of marriage she incorporates this devaluation into her self-concept.

Cognitive growth and physical development also affect body image. Normal developmental changes such as puberty and aging have a more apparent effect on body image than on other aspects of self-concept. Hormonal changes during adolescence and menopause influence body image. The development of secondary sex characteristics and the changes in body fat distribution have a tremendous impact on an adolescent’s self-concept. Early maturation is associated with lower psychological well-being and lower enjoyment of physical activity, which in turn could negatively impact body image (Davison et al., 2007). For both male and female adolescents, negative body image is a risk factor for suicidal thoughts (Brausch and Muehlenkamp, 2007). A threat to body image and overall self-concept can affect adherence to recommended health regimens, including diet and taking medications as prescribed (Thomas, 2007). Changes associated with aging (e.g., wrinkles; graying hair; and decrease in visual acuity, hearing, and mobility) also affect body image in an older adult.

Cultural and societal attitudes and values influence body image. Culture and society dictate the accepted norms of body image and influence one’s attitudes (Fig. 33-2). Racial and ethnic background plays an integral role in body satisfaction in adolescent girls and is reflected in differences in body satisfaction among groups. Further, body image is more favorable in cultures in which girls describe more reasonable views about physical appearance, report less social pressure for thinness, and have less tendency to base self-esteem on body image. Values such as ideal body weight and shape and attitudes toward piercing and tattoos are culturally based. American society emphasizes youth, beauty, and wholeness. Western cultures have been socialized to dread the normal aging process, whereas eastern cultures view aging very positively and respect older adults. Body image issues are often associated with impaired self-concept and self-esteem.

Role Performance

Role performance is the way in which individuals perceive their ability to carry out significant roles (e.g., parent, supervisor, or close friend). Normal changes associated with maturation result in changes in role performance. For example, when a man has a child, he becomes a father. The new role of father involves many changes in behavior if the man is going to be successful. Group interventions aimed at improving fathering experiences have led to significant improvements in the father’s participation in the family, including role performance, involvement, communication, self-esteem, a sense of increased competence, and decreased stress in parenting (Gearing et al., 2008). Roles that individuals follow in given situations involve socialization, expectations, or standards of behavior. The patterns are stable and change only minimally during adulthood.

Ideal societal role behaviors are often hard to achieve in real life. Individuals have multiple roles and personal needs that sometimes conflict. Successful adults learn to distinguish between ideal role expectations and realistic possibilities. To function effectively in multiple roles, a person must know the expected behavior and values, desire to conform to them, and be able to meet the role requirements. Fulfillment of role expectations leads to an enhanced sense of self. Difficulty or failure in meeting role expectations leads to deficits and often contributes to decreased self-esteem or altered self-concept.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is an individual’s overall feeling of self-worth or the emotional appraisal of self-concept. It is the most fundamental self-evaluation because it represents the overall judgment of personal worth or value. Self-esteem is positive when one feels capable, worthwhile, and competent (Rosenberg, 1965). A person’s self-esteem is related to his or her evaluation of his or her effectiveness at school, within the family, and in social settings. The evaluation of others also is likely to have a profound influence on a person’s self-esteem. For example, college athletes report greater levels of self-esteem and social connectedness and lower levels of depression than nonathletes. The positive influence of team support can protect college athletes from disturbances of self-esteem and depression symptoms (Armstrong and Oomen-Early, 2009).

Considering the relationship between a person’s actual self-concept and his or her ideal self enhances understanding of that person’s self-esteem. The ideal self consists of the aspirations, goals, values, and standards of behavior that a person considers ideal and strives to attain. In general, a person whose self-concept comes close to matching the ideal self has high self-esteem, whereas a person whose self-concept varies widely from the ideal self suffers from low self-esteem (Stuart, 2009). Once established, basic feelings about the self tend to be constant, even though a situational crisis can temporarily affect self-esteem.

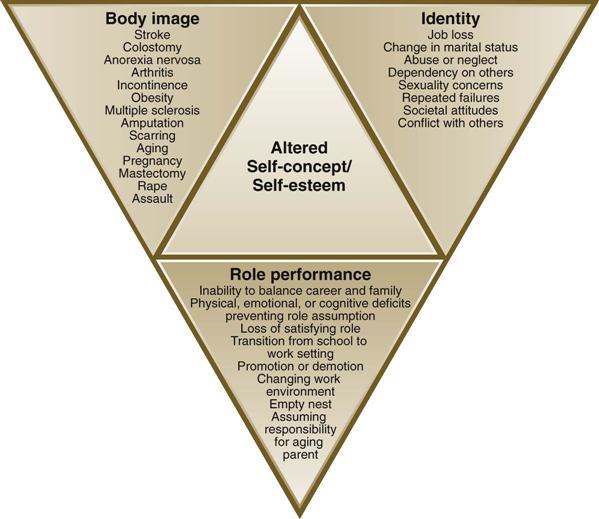

Factors Influencing Self-Concept

A self-concept stressor is any real or perceived change that threatens identity, body image, or role performance (Fig. 33-3). An individual’s perception of the stressor is the most important factor in determining his or her response. The ability to reestablish balance following a stressor is related to numerous factors, including the number of stressors, duration of the stressor, and health status (see Chapter 37). Stressors challenge a person’s adaptive capacities. Changes that occur in physical, spiritual, emotional, sexual, familial, and sociocultural health affect self-concept. Being able to adapt to stressors is likely to lead to a positive sense of self, whereas failure to adapt often leads to a negative self-concept.

Any change in health is a stressor that potentially affects self-concept. A physical change in the body sometimes leads to an altered body image, affecting identity and self-esteem. Chronic illnesses often alter role performance, which change an individual’s identity and self-esteem. Further, an essential process in the adjustment to loss is the development of a new self-concept. A loss of a partner can lead to a loss of identity and a lower self-esteem. Unlike the loss in self-esteem shown in vulnerable older adults, the resiliency demonstrated in some older adults may reflect more sophisticated cognitive strategies to manage losses.

The stressors created as a result of a crisis also affect a person’s health. If the resulting identity confusion, disturbed body image, low self-esteem, or role conflict is not relieved, illness can result. For example, the diagnosis of cancer places additional demands on a person’s established living pattern. It changes his or her appraisal of and satisfaction with the current level of physical, emotional, and social functioning. In this case assess self-esteem, effectiveness of coping strategies, and social support. During self-concept crises, supportive and educative resources are valuable in helping a person learn new ways of coping with and responding to the stressful event or situation to maintain or enhance self-concept.

Identity Stressors

Stressors affect an individual’s identity throughout life, but individuals are particularly vulnerable during adolescence. Adolescents are trying to adjust to the physical, emotional, and mental changes of increasing maturity, which results in insecurity and anxiety. It is also a time when the adolescent is developing psychosocial competence, including coping strategies (see Chapter 37).

An adult generally has a more stable identity and thus a more firmly developed self-concept than an adolescent. Cultural and social stressors rather than personal stressors have more impact on an adult’s identity. For example, an adult has to balance career and family or make choices regarding honoring religious traditions from one’s family of origin. Identity confusion results when people do not maintain a clear, consistent, and continuous consciousness of personal identity. It occurs at any stage of life if a person is unable to adapt to identity stressors.

Body Image Stressors

A change in the appearance, structure, or function of a body part requires an adjustment in body image. An individual’s perception of the change and the relative importance placed on body image affects the significance of a loss of function or change in appearance. For example, if a woman’s body image incorporates reproductive organs as the ideal, a hysterectomy needed because of a diagnosis of uterine cancer is a significant alteration and can result in a perceived loss of femininity or wholeness. Changes in the appearance of the body such as an amputation, facial disfigurement, or scars from burns are obvious stressors affecting body image. Mastectomy and colostomy are surgical procedures that alter the appearance and function of the body, yet the changes are not apparent to others when the individual is dressed. Although potentially undetected by others, these bodily changes significantly impact the individual. Even some elective changes such as breast augmentation or reduction affect body image. Chronic illnesses such as heart and renal disease affect body image because the body no longer functions at an optimal level. The patient has to adjust to a decrease in activity tolerance that impacts his or her ability to perform normal activities of daily living. In addition, pregnancy, significant weight gain or loss, pharmacological management of illness, or radiation therapy changes body image. Negative body image often leads to adverse health outcomes.

The response of society to physical changes in an individual often depends on the conditions surrounding the alteration. Some social changes have allowed the public to respond more favorably to illness and altered body image. For example, the media frequently presents positive stories about persons adjusting in a healthy manner following serious disabilities (e.g., Christopher Reeve’s spinal cord injury) or adapting to a debilitating illness (e.g., Michael J. Fox’s Parkinson’s disease). These stories change public awareness and the perception of what constitutes a disability and provide positive role models for individuals undergoing self-concept stressors and their families, friends, and society as a whole. In view of the growing epidemic of obesity in western cultures, parents and health care providers need to address weight management issues without causing further injury to body image. Providing a social environment that focuses on health and fitness rather than a drive for thinness for girls or muscularity for boys can potentially increase adolescent satisfaction with their bodies (Brunet et al., 2010).

Role Performance Stressors

Throughout life a person undergoes numerous role changes. Situational transitions occur when parents, spouses, children, or close friends die or people move, marry, divorce, or change jobs. It is important to recognize that a shift along the continuum from illness to wellness is as stressful as a shift from wellness to illness. Any of these transitions may lead to role conflict, role ambiguity, role strain, or role overload.

Role conflict results when a person has to simultaneously assume two or more roles that are inconsistent, contradictory, or mutually exclusive. For example, when a middle-age woman with teenage children assumes responsibility for the care of her older parents, conflicts occur in relation to being both a parent to her children and the child of her parents. Negotiating a balance of time and energy between her children and parents creates role conflicts. The perceived importance of each conflicting role influences the degree of conflict experienced. The sick role involves the expectations of others and society regarding how an individual behaves when sick. Role conflict occurs when general societal expectations (take care of yourself, and you will get better) and the expectations of co-workers (need to get the job done) collide. The conflict of taking care of oneself while getting everything done is often a major challenge.

Role ambiguity involves unclear role expectations, which makes people unsure about what to do or how to do it, creating stress and confusion. Role ambiguity is common in the adolescent years. Parents, peers, and the media pressure adolescents to assume adultlike roles, yet many lack the resources to move beyond the role of a dependent child. Role ambiguity is also common in employment situations. In complex, rapidly changing, or highly specialized organizations, employees often become unsure about job expectations.

Role strain combines role conflict and role ambiguity. Some express role strain as a feeling of frustration when a person feels inadequate or unsuited to a role such as providing care for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease.

Role overload involves having more roles or responsibilities within a role than are manageable. This is common in an individual who unsuccessfully attempts to meet the demands of work and family while carving out some personal time. Often during periods of illness or change, those involved either as the one who is ill or as a significant other find themselves in role overload.

Self-Esteem Stressors

Individuals with high self-esteem are generally more resilient and better able to cope with demands and stressors than those with low self-esteem. Low self-worth contributes to feeling unfulfilled and disconnected from others. Decreased self-worth can potentially result in depression and unremitting uneasiness or anxiety. Illness, surgery, or accidents that change life patterns also influence feelings of self-worth. Chronic illnesses such as diabetes, arthritis, and cardiac dysfunction require changes in accepted and long-assumed behavioral patterns. The more the chronic illness interferes with the ability to engage in activities contributing to feelings of worth or success, the more it affects self-esteem.

Self-esteem stressors vary with developmental stages. Perceived inability to meet parental expectations, harsh criticism, inconsistent discipline, and unresolved sibling rivalry reduce the level of self-worth of children. A developmental milestone such as pregnancy introduces unique self-concept stressors and has significant health care implications. For some economically disadvantaged youth, safe sex behaviors are not always valued, and pregnancy is an affirmation of ethnic identity. Low self-esteem during adolescence also has significant real-world consequences in adulthood, including poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects compared to adolescents with high self-esteem. Self-esteem and health behaviors are intertwined. Stressors affecting the self-esteem of an adult include failure in work and unsuccessful relationships. Self-concept stressors in older adults include health problems, declining socioeconomic status, spousal loss or bereavement, loss of social support, and decline in achievement experiences following retirement (Box 33-3).