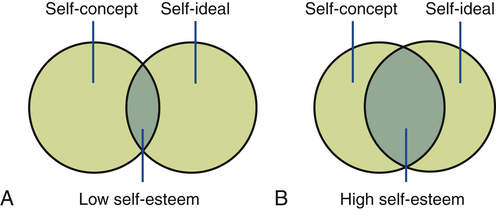

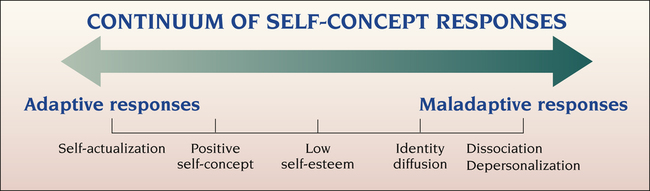

1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive self-concept responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with self-concept responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to self-concept responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to self-concept responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to self-concept responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to self-concept responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals for patients related to self-concept responses. 8. Develop a patient education plan to improve family relationships. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to self-concept responses. 10. Evaluate nursing care related to self-concept responses. The self-concept is learned in part through social contacts and experiences with other people over time. This has been called “learning about self from the mirror of other people” (Sullivan, 1963). A person’s concept of self therefore rests partly on what he thinks others think of him. For a young child the most significant others are the parents, who help the child grow and react to experiences. Parents provide the child with the earliest experiences of the following: • Feelings of adequacy or inadequacy • Feelings of acceptance or rejection • Opportunities for identification • Expectations concerning acceptable goals, values, and behaviors Figure 17-1 describes the continuum of self-concept responses from the most adaptive state of self-actualization to the most maladaptive response of depersonalization. To provide the best care the nurse needs an understanding of body image, self-ideal, self-esteem, role, and identity. Self-esteem is a person’s personal judgment of self-worth, based on how well behavior matches up with self-ideal. How frequently a person attains goals directly influences feelings of competency (high self-esteem) or inferiority (low self-esteem) (Figure 17-2). The origins of self-esteem begin in childhood and are based on acceptance, warmth, involvement, consistency, praise, and respect (Coopersmith, 1967; Mruk, 2006). The four best ways to promote a child’s self-esteem are as follows: 1. Providing opportunities for success 4. Helping the child build defenses against attacks to self-perceptions Factors that influence a person’s adjustment to a role include the following: • Knowledge of specific role expectations • Consistent responses from significant others to one’s role • Compatibility and complementarity of various roles • Congruency of cultural norms and one’s own expectations for role behavior • Separation of situations that would create incompatible role behaviors A person with a healthy personality has the characteristics listed in Table 17-1 and is able to perceive both self and the world accurately. This insight creates a feeling of harmony and inner peace. TABLE 17-1 QUALITIES OF THE HEALTHY PERSONALITY Personality fusion and problems with identity have serious implications for the larger family system. Dysfunctional families are often characterized by a fusion of ego mass that may be evident in symptomatology by one or more family members. This may be expressed in some form of family violence or abuse (see Chapter 38) or in the scapegoating of a family member. Finally, people with identity diffusion also may lack a coherent sense of history, cultural norms, group affiliation, lifestyle, or sound child-rearing practices. A related behavior may be the absence of a moral code or of any genuine inner value. The behaviors characteristic of identity diffusion are summarized in Box 17-2. Dissociation is a state of acute mental decompensation in which certain thoughts, emotions, sensations, or memories are compartmentalized because they are too overwhelming for the conscious mind to integrate (MacDonald, 2008; Weber, 2007). In severe forms of dissociation, disconnection occurs in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception. initiative. This is sometimes described as the experience of being a “passenger” in one’s own body rather than the driver. Finally, the person may exhibit behaviors related to dissociative identity disorder, known as multiple personality disorder. In this case, distinct and separate personalities exist within the same person, each of whom recurrently dominates the person’s attitudes, behaviors, and self-view as though no other personality existed (Box 17-3). The many behaviors associated with dissociation and depersonalization are summarized in Box 17-4. The following clinical example may further clarify these behaviors.

Self-Concept Responses and Dissociative Disorders

Continuum of Self-Concept Responses

Self-Concept

Developmental Influences

Significant Others

Self-Perceptions

Self-Esteem

Role Performance

Healthy Personality

CHARACTERISTIC

DEFINITION

DESCRIPTION

Positive and accurate body image

Body image is the sum of the conscious and unconscious attitudes one has toward one’s body function, appearance, and potential.

A healthy body awareness is based on self-observation and appropriate concern for one’s physical well-being.

Realistic self-ideal

Self-ideal is one’s perception of how one should behave or the standard by which behavior is appraised.

A person with a realistic self-ideal has attainable life goals that are valuable and worth striving for.

Positive self-concept

Self-concept consists of all the aspects of the self of which one is aware. It includes all self-perceptions that direct and influence behavior.

A positive self-concept implies that the person expects to be successful in life. It includes acceptance of the negative aspects of the self as part of one’s personality. Such a person faces life openly and realistically.

High self-esteem

Self-esteem is one’s personal judgment of one’s own worth, which is obtained by analyzing how well one matches up to one’s own standards and how well one’s performance compares with that of others. It evolves through a comparison of the self-ideal and self-concept.

Persons with high self-esteem feel worthy of respect and dignity, believe in their own self-worth, and approach life with assertiveness and zest. People with a healthy personality feel very similar to the person they want to be.

Satisfying role performance

Roles are sets of socially expected behavior patterns associated with functioning in various social groups.

The healthy person can relate to others intimately, receive gratification from social and personal roles, trust others, and enter into mutual and interdependent relationships.

Clear sense of identity

Identity is the integration of inner and outer demands in one’s discovery of who one is and what one can become. It is the realization of personal consistency.

People with a clear sense of identity experience a unity of personality and perceive themselves to be unique persons. This sense of self gives life direction and purpose.

Assessment

Behaviors

Behaviors Associated With Low Self-Esteem

Behaviors Associated With Identity Diffusion

Behaviors Associated With Dissociation and Depersonalization

Self-Concept Responses and Dissociative Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access