Screening and Referral

Gail L. Heiss

Focus Questions

What is the value of screening in maintaining the health of people in the community?

How is screening linked to health promotion and maintenance?

What principles guide the selection, development, and targeting of screening programs?

What is the relationship between screening and referral?

What are the responsibilities of the community/public health nurse in the referral process?

Key Terms

Case finding

Health fair

Mass screening

Multiphasic screening

Outcome evaluation

Presumptive identification of disease

Process evaluation

Referral

Reliability

Screening

Secondary prevention

Sensitivity

Specificity

Validity

An essential component in maintaining the health of a community is early detection of disease. Although ideally the hope is to prevent disease, not all diseases are completely preventable. For example, although some risk factors associated with the development of heart disease are known and can be avoided (e.g., high-fat diet, smoking, sedentary lifestyle), others are unmodifiable (e.g., age, sex, family history). For this reason, diseases that cannot be completely prevented must be detected early in their natural history when they are more amenable to treatment. The concept of early detection and treatment of disease is relevant to the Determinants of Health discussed in Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010). Determinants of health incorporate personal factors such as biology and genetics and access to health services, such as early detection and screening tests. Also included in determinants of health are social factors such as the environment in which people live and work. (See Chapter 18.)

Secondary prevention is aimed at the early detection and treatment of illness. Screening is a major strategy for secondary prevention. When previously unrecognized illnesses are identified through screening, referrals must be made for follow-up diagnosis and treatment. This chapter explores the concept of screening and the responsibilities of the community health nurse in the screening and referral process.

Definition of screening

Screening is the process of using clinical tests and/or examinations to identify patients who require diagnosis and additional health-related interventions. The goal of screening is to differentiate correctly between persons who have a previously unrecognized illness, developmental delay, or other health alteration and those who do not. Screening recommendations most often used for health screening events and routine health care appointments are based on the clinical research and evidence-based preventive care presented by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The Preventive Services Task Force is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and is recognized as the leader in prevention and screening recommendations (USPSTF, 2010). The screening recommendations may be found online or a print copy of the guide (AHRQ, 2011, publication number 10-05145) may be obtained at no cost from the AHRQ Publications Clearinghouse on a single copy basis (http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm).

Screening involves several key concepts. Screening is aimed at the presumptive identification of disease. In other words, if a screening test is positive (abnormal), one can only presume that the disease may be present. A screening test in itself is not sufficient to establish a positive diagnosis of disease because a single screening test, taken in isolation, is not always 100% accurate. For example, inaccuracies in test measurement can lead to false-positive or false-negative test results. For this reason, when a screening test is positive, a referral is made for follow-up diagnostic testing to confirm whether the disease is present.

Screening tests detect previously unrecognized disease, meaning that screening tests are often conducted on seemingly healthy populations. Persons who undergo screening tests may be asymptomatic of disease and unaware that a problem potentially exists. The goal, and value, of a screening test is to detect disease in an earlier stage than it would be if the client waited for clinical symptoms to develop before seeking help.

Screening is conducted by applying tests and procedures. These tests can be applied rapidly and inexpensively to populations. In other words, these tests should be appropriate for administration to a large group of people. To screen large groups in a timely manner, a test must be able to be administered rapidly and with ease. Tests should be relatively inexpensive so they are accessible to more economically diverse populations.

Mass screening is used to denote the application of screening tests to large populations. These groups may be typical of the general population or be selectively at a higher risk for certain problems. Because mass screening of the general population is often costly and does not necessarily detect enough new cases of disease to balance the cost of screening, money may be better spent on targeting selected populations known to be at high risk for certain illnesses. For example, in a large city where elevated lead levels in children are a problem because of inadequate housing, the community/public health nurse might suggest targeting screening toward children from minority groups and low-income children living in impoverished neighborhoods.

Case finding is screening that occurs on an individual or a one-on-one basis. Case finding uses screening tests to identify previously unrecognized disease in individuals who may present to the health care provider for health maintenance checks or for an unrelated complaint. A good example is when the community/public health nurse makes a home visit and checks the blood pressure of each member of the family. In this instance, the nurse may detect previously unrecognized disease in family members who are unaware that a problem even exists. Another example is an individual who obtains a new job and has a preemployment physical; an elevated cholesterol level may be detected in this manner.

Multiphasic screening is used to denote the application of multiple screening tests on the same occasion. A health fair held at a church, synagogue, or mosque for example, may include screening for blood pressure, depression, colorectal cancer, and diabetes. Persons may present to different stations or providers and receive several screening tests during a single visit. Table 19-1 presents some suggestions on selecting screening tests when planning a multiphasic health fair.

Table 19-1

Planning a Multiphasic Health Fair

| Nursing Process | Explanation |

| Assess: The diseases being screened should be significant health problems in the community. | Select screening tests based on demographic data and relevance of the problem to the community. For example, it would be appropriate to conduct a screening for osteoporosis at a community center serving primarily white women. |

| Plan: Gather support from the community and consider all the details. | Issues such as available dates and times, space, volunteers, funding for screening tests, advertising, and cultural issues must be considered from the beginning. For example, it would not be appropriate to conduct a hypertension screening at the Jewish Community Center during the Jewish New Year in September. |

| Implement: The screening tests should be safe, simple to administer, cost-effective, and acceptable to the client population. | Tests to consider might include screening for hypertension, diabetes, elevated cholesterol levels, and cancer. Some cancer screenings such as colon and rectal screening may be done with noninvasive fecal occult blood stool cards that the patient takes home. Invasive procedures should be avoided in mass screening settings. |

| Evaluate: Follow-up diagnosis and treatment of persons with positive test results is important. | A screening program should not be conducted unless adequate community resources are available to deal with the outcome of positive test results. If no resources exist in the community, the community/public health nurse has a responsibility to advocate for funding for such resources and to mobilize needed resources so that community health and well-being are protected. |

Criteria for selecting screening tests: validity and reliability

Validity, Sensitivity, and Specificity

Validity is defined as the ability of the screening test to distinguish correctly between persons with and those without the disease. If a screening test were 100% valid, it would never have a false-positive or false-negative reading. The result would always be positive in people who had the disease and negative in people who did not. The validity of a screening test is measured using sensitivity and specificity.

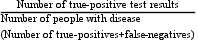

Sensitivity is the ability of a screening test to identify correctly persons who have the disease. When the disease is correctly identified, this result is known as a true-positive test. A test with poor sensitivity will miss cases and will produce a large proportion of false-negative test results; people will be incorrectly told they are free of disease. The statistical formula for calculating sensitivity is the following:

Notice that the denominator in the formula is all persons with the disease. After a screening test, persons with the disease might have a screening result that is either true-positive (i.e., they do, in fact, have the disease) or false-negative (i.e., the screening test is normal, but they do actually have the disease). The greater the number of false-negative test results, meaning the larger the number of persons with disease who have not been identified, the lower the sensitivity of the screening test.

Specificity is the ability of the screening test to identify persons who are normal or without disease and who correctly test negative when screened. The formula for specificity is as follows:

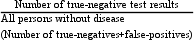

In this case, persons who are healthy may have one of two test results. They may have either a true-negative finding (i.e., they do not have the disease, and the test findings are normal) or a false-positive finding (i.e., they do not have the disease, but their screening test result is positive for disease). The greater the number of false-positive test results, the lower the specificity of the screening test. Table 19-2 summarizes sensitivity and specificity.

Table 19-2

| Sensitivity is the ability of the test to correctly identify persons who have a disease. | |

| High sensitivity | Numerous true-positive results. People who actually have the disease correctly test positive. |

| Low sensitivity | Numerous false-negative results. People have a normal screening, but actually have the disease. |

| Specificity is the ability of the test to identify persons who do not have disease who correctly test negative. | |

| High specificity | Numerous true-negative results. People who do not have disease correctly test negative. |

| Low specificity | Numerous false-positive results. People have an abnormal screening, but they do not have the disease. |

Ideally, a screening test would be 100% sensitive and 100% specific. However, because this combination of perfect accuracy and precision in measurement is not likely, screening tests are not used to confirm a diagnosis positively and are not considered to be diagnostic.

Is having a high sensitivity and a moderate or low specificity better, or should attempts be made to improve specificity, even though sensitivity may be compromised? The answer to these questions depends on the disease for which the individual is being screened and the physical, psychological, and financial impact of false-positive versus false-negative test results. In the case of diseases that are potentially fatal if not detected early, sensitivity may be more important. However, the psychological trauma and financial cost of being labeled incorrectly as having a disease can be devastating. For example, if a client receives news that he has a fatal disease, and then commits suicide, a false-positive reading has had significant consequences. In this case, high specificity is as important as high sensitivity.

An interesting discussion of sensitivity and specificity relating to school nurse screening for scoliosis is found on the iScoliosis website (http://www.iscoliosis.com/symptoms-screening.html) and in Website Resource 19A.![]() The screening of adolescents for scoliosis occurs in schools in all 50 states. The purpose of the screening is to detect scoliosis at an early stage. The test is described as sensitive (always detects the presence of scoliosis versus a normal back) and has a low false-negative rate (does not miss kids that need treatment). The test is also determined to be specific (finding scoliosis as opposed to other problems). A figure of the test and additional information on this screening test are also located in Website Resource 19A.

The screening of adolescents for scoliosis occurs in schools in all 50 states. The purpose of the screening is to detect scoliosis at an early stage. The test is described as sensitive (always detects the presence of scoliosis versus a normal back) and has a low false-negative rate (does not miss kids that need treatment). The test is also determined to be specific (finding scoliosis as opposed to other problems). A figure of the test and additional information on this screening test are also located in Website Resource 19A.

Reliability of Screening Tests

Reliability refers to the consistency or reproducibility of test results over time and between examiners. A test is reliable when it gives consistent results when administered at different times and by different persons

Contexts for screening

Screening programs may be targeted to individuals (i.e., case finding) or to populations (i.e., mass screening). For individuals, screening tests are selected based on the client’s personal history and risk factors. Population-based mass screenings can be offered in conjunction with national screening days, such as skin cancer screening or depression screening, or they may be selected based on demographic and epidemiological data.

Screening of Individuals

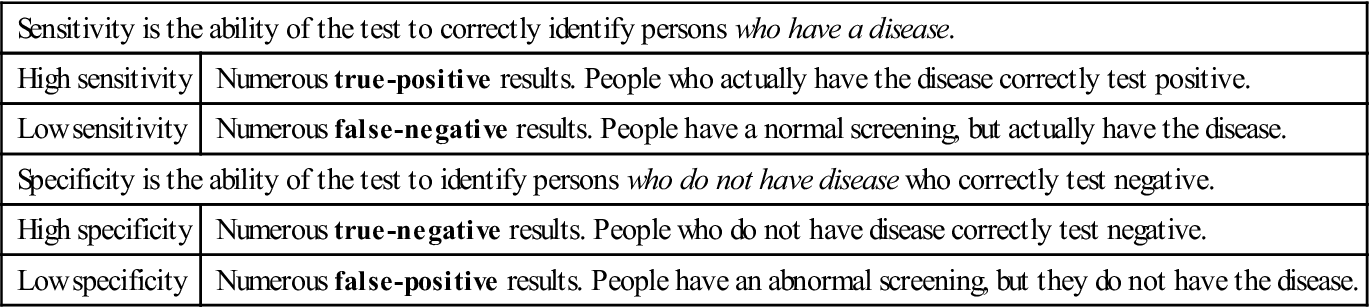

A routine health-maintenance examination is one example of a multiphasic, case-finding intervention. Periodic health checkups include a comprehensive health history, physical examination, and relevant laboratory and diagnostic studies. Many health care providers and organizations follow the screening guidelines available through the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). The NGC is sponsored by the AHRQ and provides recommendations based on evidence-based clinical practice (http://www.guideline.gov). This website organizes recommendations for periodic screening of adults by topic such as hypertension, lipid disorders, obesity, colorectal cancer, and others (NGC, 2011). The site includes comparisons and recommendations of other key agencies and highlights similarities, differences and evidence-based resources. Several screening guidelines are presented in Table 19-3.

Table 19-3

Recommendations for Selected Adult Health Screenings

| Screening Method | Recommendation |

| Breast Cancer Screening | |

| Breast self-examination* | Indicated once a month for women older than 20 years |

| Clinical breast examination* | Women younger than 40 years: every 3 years |

| Women 40 years and older: every year | |

| Mammography* | Annually ages 40 and older |

| Colon/Rectal Cancer Screening for Men and women* | |

| Tests That Find Polyps and Cancer | |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | Every five years starting at age 50 |

| Colonoscopy OR Double contrast barium enema OR CT colonoscopy (virtual colonoscopy) | Every 10 years starting at age 50 Every five years starting at age 50 Every five years starting at age 50 |

| TestS that mainly find cancer | |

| Fecal occult blood test with at least 50% test sensitivity for cancer or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) with at least 50% test sensitivity for cancer | Annual, start at age 50 Note: A take-home multiple sample method should be used. A digital rectal exam in the doctor’s office is not adequate for screening. |

| Papanicolaou test women 18 +* | Start 3 years after a woman starts having vaginal intercourse, but no later than age 21. At or after age 30, women who have had three consecutive normal tests may get screened every two to three years with cervical cytology or every three years with an HPV DNA test plus cervical cytology. Women 70 or older who have had three or more normal pap tests and no abnormal test in the past 10 years or who have had a total hysterectomy may choose to stop cervical cancer screening. |

| Testicular self-examination* Prostate specific antigen (PSA) test with or without digital rectal exam. Men age 50 +* BLOOD PRESSUREBlood Pressure and Classification of Hypertension†Normal: Systolic less than 120 mm Hg; diastolic less than 80 mm HgPrehypertensive: Systolic 120-139 mm Hg; diastolic 80-89 mm HgHypertensiveStage 1: Systolic 140-159 mm Hg; diastolic 90-99 mm HgStage 2: Systolic ≥ 160 mm Hg; diastolic ≥ 100 mm Hg | Monthly for postpubertal malesAsymptomatic men with at least a 10-year life expectancy should have an opportunity to discuss risks and benefits of screening and make an informed decision with their health care provider.Recommendations for Referral to a Source of Medical Care Normal: Recheck in 2 yearsPrehypertensive: Recheck in 1 year; provide advice about lifestyle modificationsHypertensiveStage 1: Confirm within 2 months; provide advice about lifestyle modificationsStage 2: Evaluate or refer to source of care within 1 month; for those with pressures ≥180/110 mm Hg, evaluate and treat immediately or within 1 week, depending on clinical situation |

| Cholesterol‡ Desirable values: | Check once every 5 years or more frequently if indicated |

| Total cholesterol: less than 200 mg/dl | |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) “bad” cholesterol: less than 100 mg/dl optimal | |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) “good” cholesterol: 40-60 mg/dl | |

| Triglycerides: less than 150 mg/dl | |

| Diabetes screening§ | Annually for high-risk individuals (e.g., family history, personal history of glucose intolerance, obesity, older than age 45 years, people from minority races); otherwise during routine medical examinations |

| Screening may be verbal or written; only individuals with high risk or physical symptoms should be referred for blood testing | |

| Skin cancer screening¶ | Complete body skin examination every 3 years ages 20 to 40 years, annually ages 40 and older |

| Mantoux test with purified protein derivative-tuberculin (PPD) skin test** | Annually for high-risk groups (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-positive persons, known contact with tuberculosis patient, immunosuppressed persons, persons who live or work in long-term care facilities or work in hospitals or schools, foreign-born persons from countries with high tuberculosis rates, persons living in the United States in areas where TB is common such as a homeless shelter, persons who inject illegal drugs); otherwise as indicated |

*American Cancer Society. (2011). Cancer facts and figures. Screening guidelines. Available online at http://www.cancer.org.

**Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Testing for TB infections. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/tb.

†National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. (2004). The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Washington, DC: Author. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines.

‡National Cholesterol Education Program. (2007). Guidelines for clinical preventive services. Washington, DC: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines.

§American Diabetes Association. (2007). Facts and figures. Available at http://www.diabetes.org.

¶American Academy of Dermatology. (2011) Skin cancer prevention. Available at http://www.aad.org.

In addition to screening guidelines, the nurse and the patient may use family history to determine which screening tests are most appropriate. A useful tool for documenting family health history called My Family Health Portrait, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011), Office of the Surgeon General, can be completed online, saved, and printed for use during visits with the health care provider. The tool is available in English, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese at https://familyhistory.hhs.gov/fhh-web/home.action.

Another health tool of interest designed specifically for African American families is a collaborative education and awareness program developed in 2006 by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Stroke Association called the Power to End Stroke. The materials include a family reunion toolkit including suggestions for compiling a family health history and a tool for documenting stroke awareness and the importance of seeking medical care if a family member has two or more risks factors such as elevated blood pressure, elevated cholesterol or a history of physical inactivity (http://powertoendstroke.org/tools-family-reunion.html).

Screening of Populations

On a population level, choice of screening tests is based on general sociodemographic rather than individual risk factors. To determine what screening tests should be administered, the community health nurse must assess the risks inherent in the target population. What diseases are the target population most at risk of developing? Are these diseases easily screened?

Age, gender, and ethnicity factors have an impact on the risk status of a population. A nurse planning a health fair in a local women’s center, for example, may include screening for breast cancer. An individual attending the health fair may not be at an increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age or personal and family history. Nevertheless, because the population group as a whole has been determined to be at risk, instruction on breast self-exam and information on recommendations for mammography and sources for screening mammograms are made available.

African American men are at a higher risk of developing malignant hypertension than are women or white men; therefore advertisements for some health fairs might be targeted to the African American community. Osteoporosis is more common in white and Asian postmenopausal women than it is in other population groups; thus a women’s event might be a good place for this screening. Population data are an important consideration for nurses planning mass screenings.

Major Health Threats in the General Population

Chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes are the leading causes of death and disability in the United States. Heart disease and stroke, the first and third leading causes of death, account for more than one-third of all U. S. deaths. In 2007 of all adults who died of cardiovascular disease, 150,000 were under age 65 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011a). Cancer, the second leading cause of death, is responsible for the deaths of more than 1500 people every day in the United States (CDC, 2011a). The cost of chronic disease is also dramatic. It is estimated that the direct and indirect (such as loss of productivity) costs of cardiovascular disease and stroke in the United States in 2011 were $444 billion. The financial costs of cancer, the second leading cause of death, responsible for over 560,000 deaths in 2007 alone, also are overwhelming. According to the National Institutes of Health, cancer costs the United States an estimated $263.8 billion in medical costs and lost productivity in 2010 (CDC, 2011a).

Mental illnesses are also major threats to the health of the general population. In addition to screening for physical problems, community/public health nurses can also screen for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. (See Chapters 25 and 33.)

Cardiovascular Disease, Stroke, and Hypertension

The principal risk factors for heart disease and stroke include hypertension (blood pressure reading of 140/90 mm Hg or higher), elevated serum cholesterol level (greater than 200 mg/dl), tobacco use, overweight and obesity, family history of atherosclerotic disease, advancing age, and physical inactivity (CDC, 2011b). A surprising fact for some health care consumers is that although cardiovascular disease is frequently considered a male health problem, cardiovascular disease is the leading killer of women in the United States. It is estimated that one in two women will die of heart disease, compared to one in 25 who will die of breast cancer. More than half of the total deaths each year from heart disease occur in women. Women continue to have limited knowledge about risk factors and symptoms of coronary heart disease. Assessment of women’s knowledge with subsequent education and behavior modification is a viable strategy to promote healthy lifestyle and risk reduction (Thanavaro et al., 2010).

Many of the risk factors related to cardiovascular disease are modifiable, making cardiovascular disease highly amenable to prevention efforts. Selected Healthy People 2020 objectives for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease through secondary prevention measures are presented in the Healthy People 2020 box. In addition to the initiatives related to Healthy People, in 2006 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created the Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (DHDSP), which provides national leadership and research to reduce the burden of disease, disability, and death from heart disease through strategies and policies that promote healthy lifestyle, healthy environments, and access to detection and treatment.

Hypertension

Screening programs aimed at the early identification of hypertension contribute greatly to the early diagnosis and treatment of this potentially fatal condition by making people aware of their blood pressure status and by referring those with elevated readings for follow-up diagnosis and treatment. A committee representing the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) publishes guidelines every few years to guide the diagnosis and clinical treatment of hypertension. In May 2004 the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7) published the guidelines, which are reflected in Table 19-3. (The next report is scheduled for publication in spring 2012). In addition to the guidelines, the report indicated that nearly 30% of adults in the United States remain unaware of their blood pressure, and the report discussed the strain that undiagnosed and untreated hypertension places on the health care system (NHLBI, 2004). It is estimated that an average reduction of 12-13 mm Hg of systolic pressure over 4 years can reduce the total cardiovascular disease deaths in the United States by 25% (CDC, 2011b).

Serum Cholesterol

Elevated serum cholesterol is a significant risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease. Current guidelines for cholesterol levels are seen in Table 19-3. Lifestyle changes including dietary changes and increased physical activity are emphasized by the American Heart Association. Screening for cholesterol is emphasized because persons with elevated serum cholesterol have no symptoms. (AHA, 2011).

In 1985 the NHLBI initiated the National Cholesterol Education Program to increase public awareness of the relationship between cholesterol level and heart disease. The program continues to update detailed guidelines for identifying and treating individuals with elevated serum cholesterol levels. The clinical guidelines for cholesterol health known as the ATP III Guidelines are available online (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov). Initiating cholesterol screening programs in the community may assist in preventing heart disease through early identification of at-risk persons and counseling and referral for interventions aimed at modifying dietary fat consumption, instituting exercise programs, or initiating pharmacotherapy to reduce blood lipid levels. Figure 19-1 shows a screening for cholesterol and glucose. In addition, efforts are being made to include children and families in healthy lifestyle choices as a way to promote heart health. Online education and self-risk tests for adults and children are found on the American Heart Association (http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Conditions/ _UCM_001087_SubHomePage.jsp) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute websites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree