Scope of Gerontological Nursing Practice

Definition and Description

Gerontological nursing is an evidence-based nursing specialty practice that addresses the unique physiological, psychosocial, developmental, economic, cultural, and spiritual needs related to the process of aging and care of older adults. Gerontological nurses collaborate with older adults and their significant others to promote autonomy, wellness, optimal functioning, comfort, and quality of life from healthy aging to end of life. Gerontological nurses lead interprofessional teams in a holistic, person-centered approach in the specialized care of older adults.

Gerontological nurses are the healthcare professionals consistently responsible for the 24-hour care of older adults across clinical settings. In addition to providing direct care and coordinating services for older adults, gerontological nurses advocate, educate, manage, consult, and conduct research about the dynamic trends, issues, and opportunities related to aging and its effect on older adults. Gerontological nurses have deliberately chosen this title to reflect alignment with gerontology, the scientific study of the process and problems of aging, rather than the more limiting branch of medicine known as geriatrics, which is concerned with the medical problems and care of the aged.

As early as the 1920s, a few visionary nurses called for the development of gerontological nursing practice because a body of knowledge and skills related to care of older adults across all settings was uniquely distinguishable. Today’s healthcare environment—with its increasing focus on aging issues, quality of care, quality of life, access to affordable health care, ethics, and detailed advance directives— is constantly changing.

Various assumptions of aging drive the gerontological nurse’s approach and philosophy of care, including:

Aging is a progressive, irreversible, and natural process that begins at conception.

All people age differently as a result of genetics and life experiences.

Older adults can age with high mental and physical function.

The percentage of older Americans will continue to rise because of changing demographics and increasing life expectancy in the United States.

Aging encompasses physical, cognitive, emotional, psychological, sociological, and spiritual changes.

Older adults are a heterogeneous population with varied cultural beliefs and life experiences that contribute to individual well-being and quality of life.

Older adults seek self-fulfillment and interaction with their environment.

Older adults are capable of making, and desire to make, informed decisions on how they live and how they die.

Older adults often experience multiple, interacting, acute, and chronic conditions.

The older adult’s atypical response to many diseases and illnesses often delays prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Readership

Registered nurses, especially those who consider themselves gerontological nurses, in every role and setting comprise the primary readership of this professional resource, Gerontological Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (ANA, 2001). Students, nurse administrators, interprofessional colleagues, agencies, and organizations will find this an invaluable reference. Legislators, regulators, legal counsel, and the judiciary system will also want to examine this nursing specialty scope of practice statement and accompanying standards of practice and professional performance. Last, but not least, the older adults, families, communities, and populations using healthcare and nursing services can use this document to understand better what constitutes gerontological nursing and its members—registered nurses (RNs) and advance practice registered nurses (APRNs).

Today’s Context for Gerontological Nursing Practice

It is well documented that the populations of the United States and the world are aging. The number of older adults in the United States will almost double between 2005 and 2030. The baby boomer generation begins to turn 65 years old in 2011 (IOM Report, 2008). The ever-widening

diversity of population groups highlights the need for culturally sensitive gerontological nurses.

diversity of population groups highlights the need for culturally sensitive gerontological nurses.

In addition to the growing numbers of older adults, the oldest-old (including centenarians) are increasing as well. These changing demographic characteristics and the increasing recognition of disability and frailty across the aging spectrum contribute to an unprecedented diversity in the older population. These older adults will have very different needs and preferences related to their care. Technological advances have increased the lifespan of older adults and have contributed to an unprecedented increase in surgical interventions and use of intensive care unit services. Analysis of Medicare data has shown that the significant preponderance of financial expenditures for older adult care occurs in the last six months of life (Hoover, Crystal, Kumar, Sambamoorthi, & Cantor, 2002).

Most older adults live in the community, outside the walls of institutions, and manage their lives relatively independently. A majority of older adults live with at least one chronic condition and rely on healthcare services far more than other segments of the population. Because of their increasing life expectancy, primary (health promotion), secondary (early diagnosis and treatment), and tertiary (restoration and rehabilitation) prevention strategies are appropriate and critical for older adults. However, many myths and stereotypes about aging and older adults exist and interfere with timely, evidence-based quality care to meet the healthcare needs of older adults.

The prevalence of chronic illness increases with an aging population. The development of a chronic illness trajectory provides time for the identification, treatment, and education necessary for adaptation and better living with a chronic condition. Gerontological nurses have the expertise to assist older adults in the self-management of their specific chronic conditions. They can also work with families in identifying the role they can take to partner with older adults to improve their longevity and quality of life.

Evolving models of care for older adults related to living well in the context of having a chronic illness are emerging to meet the diverse needs of an aging population. Systems designed to deliver holistic, person-centered, and coordinated care are now available and continue to be developed specifically for older adults. Community-based housing

options and related services enable many older adults to remain in their homes or relocate to group-type housing. The traditional setting of long-term care is slowly changing.

options and related services enable many older adults to remain in their homes or relocate to group-type housing. The traditional setting of long-term care is slowly changing.

Although Medicare has expanded its coverage to some preventive services, such as screenings for specific cancers, some vaccinations, bone density screening, and diabetes monitoring, many gaps in coverage remain. Medicare does not pay for hearing aids. Dental care is not covered despite growing evidence that oral health has a direct impact on overall health. Medicare’s acute care focus persists, although the healthcare needs of the majority of its policy holders are related to chronic illnesses.

Family caregivers are an integral part of community-based care for the aging population. Many of these individuals assume the role of care provider without the benefit of formal and informal healthcare education. Family caregivers provide much-needed care and support to older individuals, and at the same time balance full-time employment, often with child care responsibilities. They fill in the gaps that exist in today’s healthcare delivery system. In many instances, family caregivers neglect their own health and jeopardize their financial stability by paying out of their own pockets for services, supplies, and medications not covered by insurance.

History and Evolution of Gerontological Nursing as a Specialty Practice

In 1906, the first article addressing care of the aged was published in American Journal of Nursing. Historically, care of older adults had been delegated to the nursing profession and not to medicine.

Lowering the cost of caring and maintaining sick older adults had its beginnings with Florence Nightingale and Agnes Jones during the 1800s in England. Consider that in the early 1900s, life expectancy was about 47 years. During this time, care was provided by family members. From 1800 to the 1930s, almshouses were a norm of care for various groups of poor people. They experienced separation from society and were placed in areas considered to meet common issues; i.e., asylums for the insane, jails for criminals, and foster homes for children. It was during this time that Lavinia Dock, a nurse, and Carolyn Crane, a social activist, found themselves attending to the chronically ill who were elderly. In 1912, the American Nurses Association Board of Directors created

a committee to supervise nursing services in almshouses. The World War I era of 1910 to 1920 included efforts at improving nursing services at almshouses. In 1925, American Journal of Nursing ran an article that “called for nurses to consider a specialty in nursing care of the aged” (Ebersole and Touhy, 2006).

a committee to supervise nursing services in almshouses. The World War I era of 1910 to 1920 included efforts at improving nursing services at almshouses. In 1925, American Journal of Nursing ran an article that “called for nurses to consider a specialty in nursing care of the aged” (Ebersole and Touhy, 2006).

During the 1930s, almshouses became nursing homes and, with the passing of the Social Security Act in 1935, an elderly individual was able to purchase care with these funds. There was no regulation of care, and the number of professional nurses was low. However, this changed in the 1940s, when public health nurses conducted inspections, identified deficiencies, and made evaluations public. There was emphasis on rehabilitation of the elderly. Nursing homes were thriving in the 1950s, and the Kerr-Mills Medical Assistance to the Aged Act provided direct payment to care providers. In 1950, the first book on nursing care of older adults was written by Newton and Anderson. In 1952, the first research article was published on chronic disease and the elderly in the generic issue of Nursing Research.

Numerous policy changes occurred during the 1960s and 1970s, in part as a result of increased government involvement, research, and the growing numbers of older adults. By 1961, 15 million Americans were older than 65, and life expectancy was approaching 70 and beyond. In 1965, the Medicare and Medicaid program began and the Older Americans Act became a cornerstone to improve the quality of life for older adults. At Duke University School of Nursing, Virginia Stone (1966) developed the first master’s degree program in gerontological nursing specific to the role of clinical nurse specialists. With federal funding from the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the 1970s brought about the expansion of programs in nursing schools for gerontological nurse practitioners (NPs) and gerontological clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) that focused on care of the elderly.

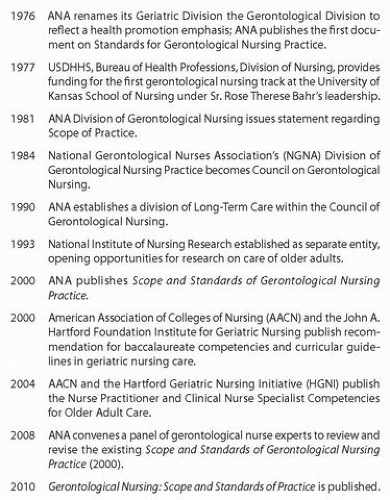

Late in the 1980s, nursing research showed that improved care of the older adult can be achieved and should be an appropriate expectation within the nursing profession. Infusion of evidence-based practice in the clinical care of older adults is a vital component in nursing education and in all healthcare facilities. Some key events in gerontological nursing of the last four decades are highlighted in the chronology in Figure 1.

The continuing need for more registered nurses and advanced practice nurses who have included or attained certification in gerontological nursing remains a reality as we move into the second decade of the 21st century. Several entities have provided funding and support to increase the availability of gerontological nursing education through formal academic education or continuing education and certification programs.

Practice Settings for Gerontolgical Nursing

Whatever the setting, gerontological nursing is a person-centered approach to promoting healthy aging and the achievement of well-being. It enables the person and their caregivers to adapt to health and life changes and to face ongoing health challenges (Kelly et al 2005). Eliopoulos (2010, p. x) has stated, “… that if done properly, gerontological nursing is among the most complex, dynamic specialties nurses could select. To practice this specialty effectively, nurses need to have a sound base in gerontology and geriatric care, an appreciation for the richness of unique life experiences, and the wisdom to understand that true healing comes from sources that exceed medications and procedures.”

The goal of gerontological nursing care is to help older adults function as fully as possible by realizing their highest potential. Collaboration with older adults promotes well-being and the optimization of functional abilities. The gerontological nurse may need to engage in a strong advocacy role when supporting the older adult in such events as making end-of-life decisions; wishing to age in place and not be displaced from familiar surroundings; and escaping from abuse, neglect, or exploitation from family, friends, or others. Research findings are incorporated through the application of theory and evidence-based nursing therapeutics to meet the older adult’s goals and expected outcomes (Capezuti, Zwicker, Mezey, & Fulmer, 2008). Gerontological nurses care for older adults in a variety of practice settings: home, acute care, short- and long-term nursing facilities, and community-based programs.

Many healthcare facilities that have become specializezd centers focusing on care and treatment of cancer and cardiovascular disease benefit from a strong gerontological nursing presence. Private and group practices employ gerontological nurses who oversee the health care of their designated panel of older adults and consult with colleagues as needed for others. Gerontological nurses play a significant role in identifying and establishing healthcare services for the often hidden and very vulnerable older adults living on the street, in homeless shelters,

and corrections facilities. Gerontological nurses are also present in faith-based communities, assisted living and group home settings, and Alzheimer and dementia care facilities.

and corrections facilities. Gerontological nurses are also present in faith-based communities, assisted living and group home settings, and Alzheimer and dementia care facilities.

Gerontological nurses may combine practice with academics in faculty positions in nursing, medical, and other health professional schools. They may play non-clinical roles in the planning, policy, and operations sectors of government programs, community organizations or agencies, or research centers. Gerontological nurses may choose to continue their advocacy initiatives through election or appointment to public office in local, state, or national legislative or regulatory bodies, including those entities that provide emergency preparedness and disaster response. International organizations and agencies are addressing the world’s aging population and need gerontological nurses to inform discussions and direct and staff the associated initiatives.

Gerontological nurses in every setting use the nursing process as the essential methodology by which the older adult’s goals are identified and achieved. The nursing process comprises assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation. Additionally, coordination of care has been shown to be essential. The accompanying standards of gerontological nursing practice and the associated measurement criteria provide a detailed description of these nursing activities.

Education of the Gerontological Nurse

The Institute of Medicine’s 2008 report, Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce, includes the dire prediction of a scarcity of all types of adequately prepared healthcare workers to care for the growing population of older adults. This includes a scarcity of registered nurses even minimally prepared to meet the preferences and needs of an aging population. There is an acute shortage of nurses choosing to specialize in gerontological nursing; less than 1% of the registered nurses in the United States are certified in gerontological nursing (Stierle et al., 2006).

Studies show that adults 65 years and older represent almost 50% of all admissions to hospitals. Consequently, many hospitals recognize that their nurses need the specialty knowledge of gerontological nursing

in order to meet the needs of their older adult patients (Stierle et al., 2006). In order to meet The Joint Commission (TJC) criteria on patient safety, nurses working in accredited hospitals need to embrace the knowledge and skills required to identify geriatric syndromes and know-how to prevent iatrogenic complications. The older adult often presents at admission with numerous chronic illnesses and multiple medications, sometimes described as polypharmacy. Because the older adult is physiologically more susceptible to drug interactions, the gerontological nurse’s recognition of subtle signs and symptoms can avoid an iatrogenic episode. The gerontological nurse’s astute assessment helps older adults to avoid circumstances that compromise their health, safety, and well-being.

in order to meet the needs of their older adult patients (Stierle et al., 2006). In order to meet The Joint Commission (TJC) criteria on patient safety, nurses working in accredited hospitals need to embrace the knowledge and skills required to identify geriatric syndromes and know-how to prevent iatrogenic complications. The older adult often presents at admission with numerous chronic illnesses and multiple medications, sometimes described as polypharmacy. Because the older adult is physiologically more susceptible to drug interactions, the gerontological nurse’s recognition of subtle signs and symptoms can avoid an iatrogenic episode. The gerontological nurse’s astute assessment helps older adults to avoid circumstances that compromise their health, safety, and well-being.

Many, but not all, schools of nursing have gerontological nursing courses in their undergraduate nursing curricula. One of the barriers to the development of such courses is the lack of faculty prepared in gerontological nursing. Recognizing this critical need, the John A. Hartford Foundation funded the Geriatric Nursing Education Consortium (GNEC), a national initiative of the American Association of Colleges of Nurses (AACN) and the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. The goal of this initiative is to educate nursing faculty in the fundamentals of gerontological nursing and the use of gerontological curriculum resources. The Hartford Foundation also funded the Geropsychiatric Nursing Collaborative to enhance the knowledge and skills of nursing to provide improved mental health care to older adults.

Distance education incorporates the rapid advances in communications technology to provide students, and practicing registered nurses, access to degree offerings and continuing education programs in gerontological nursing. Because the Internet and the World Wide Web are also sources of information for older adults and their families, the gerontological nurse must be prepared to guide older adults, family members, and caregivers in the skillful, informed, and effective use of these resources.

History of Gerontological Nursing Education

Although in roughly the same time frame, the development of the education of entry-level and advanced-level gerontological nurses have been distinct enough to merit their own summary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree