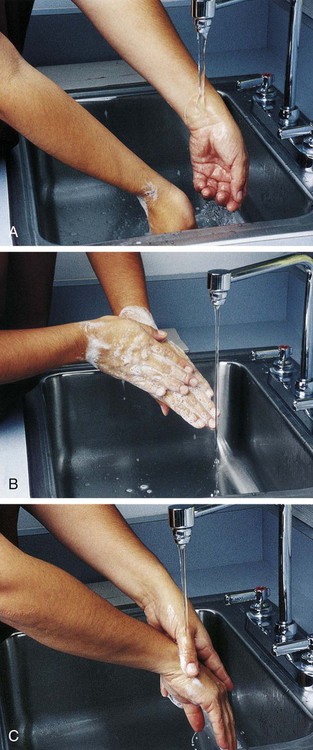

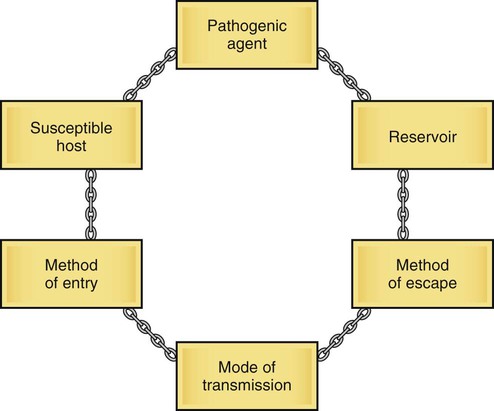

Chapter 3 Asepsis (a-SEP-sis) Freedom from infection; the methods used to prevent the spread of microorganisms The microbes or agents include anything that can cause communicable disease, such as bacteria, virus, fungi, protozoa (protists), or animals like worms. The source or reservoir for the microbe may be the patient, other people, or nonliving (inanimate) objects. Five main methods of transmission include contact, droplet, airborne, common vehicle, and vectors. Contact transmission may be direct or indirect (through an inanimate object). Common vehicle transmission includes items such as water, food, or contaminated equipment. Vectors or organisms that can spread the agent include mosquitoes, flies, rats, and other such vermin (pests). The host that does not have enough resistance to (i.e., is susceptible to) the infecting agent will become sick. Resistance may be lowered by poor nutrition, open wounds, invasive therapies such as an intravenous line, or a suppressed immune system. For infection to occur, all six of the elements of the infectious process must be present in order. The chain of infection or transmission can be broken and the infection prevented at any of the links (Fig. 3-1). In the past, isolation procedures and precautions were based on the patient’s diagnosis (Box 3-1). Someone with an infection was separated from others to prevent the spread of the microorganisms. In 1996 the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) of the CDC established a two-level set of guidelines for isolation precautions designed for acute care hospitals. The two levels are Standard Precautions, which are applied to all patients, and Transmission-Based Precautions, which are applied to patients with known or suspected infections. These guidelines also may be applied to other health care delivery systems (Table 3-1). TABLE 3-1 Transmission-Based Precautions* *All Transmission-Based Precautions are used in addition to Standard Precautions. Standard Precautions combine features of the previously used Universal Precautions and Body Substance Isolation guidelines. They are applied at all times to all patients and all body fluids except perspiration. They are designed to prevent transmission of HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and other bloodborne pathogens when providing first aid or health care (Box 3-2). All body fluids of all patients are considered to be potentially infectious under the Standard Precautions guidelines. Body fluids that are included in the precautions include blood, semen, vaginal secretions, and tissues such as pleural, peritoneal, pericardial, cerebrospinal, amniotic fluids, and nonintact skin. Handling of feces, sweat, nasal secretions, urine, tears, and vomitus does not require Universal Precautions unless they contain visible blood. Contact with saliva only requires Standard Precautions when contaminated by blood and in the dental setting. Standard Precautions do not apply to breast milk except when contact is long such as in milk banking. The primary method of protection from infection is good handwashing technique (Fig. 3-2). The hands are washed thoroughly at the beginning of the work period, between each patient contact, before and after eating, before and after using the restroom, and before leaving the work environment. Although state standards vary, the hands should be washed for a minimum of 20 seconds. Sterile gloves may be required to protect the patient during care or procedures (Fig. 3-3). Nonsterile gloves are worn when contact is made with body fluids, mucous membranes, or wet secretions. When removed, nonsterile gloves are placed directly in the designated receptacle to prevent contamination of any environmental surface. The hands are washed thoroughly immediately after removal of the sterile or nonsterile gloves. (See Skill List 3-1, Handwashing, and Skill List 3-2, Sterile Gloving, p. 56). Infections acquired by the patient as a result of the care or as a result of pathogens in the facility are called nosocomial. In the United States, about two million people acquire a nosocomial infection while in the hospital each year. Epidemiology is a science devoted to studying health-related events in the human population. Principles of epidemiology are used to trace the source and minimize the risk of nosocomial and other infections. Of the infections acquired in the hospital, the CDC reports that 70% are resistant to at least one of the drugs commonly used to treat them. The most relevant nosocomial pathogen in the United States is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The main mode of transmission of MRSA to patients is by the hands, usually of the health care worker. Box 3-3 provides more information about MRSA. When antibiotics are used to treat infection, there is a chance that microorganisms will develop resistance to them. Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms are created when some but not all of those being treated are killed. The few pathogens that survive an antibiotic treatment may develop resistance to it. That resistance is passed on to the generations of the pathogen that follow. Two factors associated with development of antibiotic resistance are overuse of antibiotic treatment and incomplete cycles of prescribed antibiotics. In 2005 the CDC listed eight diseases that have been connected to antibiotic resistance (Box 3-4). Special Transmission-Based Precautions or isolation may be used for antibiotic-resistant microorganisms (superbugs) and patients with immunosuppressed conditions. Isolation guidelines may also be used in the event of the use of bioterrorism agents such as anthrax (Box 3-5). The most common method of transfer of pathogenic organisms that cause serious illness in the health care worker is contact with a contaminated needle or sharp instrument. To prevent contamination, needles should not be recapped but should be disposed of in a container specifically designed for that purpose. Other environmental risk factors are minimized with the use of hepatitis B vaccination and devices for cardiopulmonary resuscitation that eliminate mouth-to-mouth contact with mucous membranes during the procedure. Methods that are not considered effective include disposable eating utensils, “protective” isolation, disinfectant fogging, and double bagging for the removal of waste and linens. Waste and linen should all be disposed of according to individual agency specifications designed to prevent contact with secretions. More information regarding the infection process and disease transmission is found in Chapter 22.

Safety Practices

Define at least 10 terms relating to safety practices in health care.

Define at least 10 terms relating to safety practices in health care.

Describe the infectious process and methods to prevent infection.

Describe the infectious process and methods to prevent infection.

Describe the methods of Standard and Transmission-Based Isolation Precautions that prevent the spread of microorganisms.

Describe the methods of Standard and Transmission-Based Isolation Precautions that prevent the spread of microorganisms.

Describe three levels of medical asepsis.

Describe three levels of medical asepsis.

List at least three principles of surgical asepsis.

List at least three principles of surgical asepsis.

Identify the functions of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Identify the functions of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Describe the guidelines for using good body mechanics.

Describe the guidelines for using good body mechanics.

Describe the signs and symptoms of general and localized infection.

Describe the signs and symptoms of general and localized infection.

Disease Transmission

The Infectious Process

A reservoir where the microorganism can live

A reservoir where the microorganism can live

A way of exit or escape from the reservoir

A way of exit or escape from the reservoir

A way for transmission or transfer to the host

A way for transmission or transfer to the host

Infection Control

Isolation Precautions

Type

Sample Infection

Precautions

Airborne

Measles, varicella, tuberculosis

Private room, respiratory protection (mask), special air handling and ventilation

Droplet

Diphtheria, pneumonia, pertussis, streptococcal pharyngitis, scarlet fever, adenovirus, influenza, mumps

Private room, mask, patients positioned at least 3 ft apart

Contact

Gastrointestinal, respiratory, skin or wound infections, diphtheria, herpes simplex virus, impetigo, pediculosis, viral or hemorrhagic conjunctivitis and infections (Ebola, Lassa, Marburg), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA)

Private room, gloves, gowns, handwashing with antimicrobial soap after removal of gloves, cleaning and disinfecting equipment

Safety Practices

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access