Values of Healthcare Professionals

Healthcare delivery involves a diverse and amazing tapestry of highly specialized professions. This makes teamwork in healthcare delivery more challenging than in virtually any other sphere of human work activity. It requires that professionals go to extra lengths to learn about the other members of their teams so that each team member can call on all the others to contribute everything they are able to offer in the service of patients or in the support of patient care. In this chapter we describe and compare the roles, education, and values of the professionals who are the most common members of healthcare teams.

WHY UNDERSTAND OTHER PROFESSIONS?

Newly graduated with the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree and employed by Community Medical Center for 1 month, pharmacist Jerry Young turned to his colleague, Nancy Burns, BSPharm, for advice. Ms. Burns had worked at Community Medical Center for all of her 30-year career. Dr. Young asked, “How often do the physicians and nurses in the hospital call you for advice? I’ve been here a month now, and I’ve only talked to you and other pharmacists and patients. I think I could contribute more by giving more input into decisions about prescriptions and side effects. It would prevent some issues that I think some patients will have down the road.” Ms. Burns thought awhile and carefully commented, “I get several inquiries a week from physicians, and a few from nurses. I imagine you will get some calls, once people get to know you. We don’t have a lot of opportunities to share our knowledge with the clinical staff, though, so it may take a few years. Nurses and physicians are becoming more receptive to suggestions by pharmacists, but change is slow. Many physicians and some nurses still think that we spend our days counting pills, sad to say.”

Dr. Young’s dilemma is a common one in healthcare delivery. Changes in knowledge occur more and more rapidly, and workplace roles in several healthcare professions are undergoing transformation as newly trained graduates become qualified to dispense new knowledge and provide new services. As a recent PharmD graduate, Dr. Young may have different expectations for his role than his colleague Ms. Burns has. Indeed, Dr. Young holds a doctoral-level degree, now the entry-level degree for pharmacists, compared to Ms. Burns’ baccalaureate degree (therefore the appellation Dr. for Jerry Young). Ms. Burns was educated, trained, and worked in an earlier era of healthcare delivery. New practitioners enter a workforce in which old patterns of interaction are difficult to change. Practitioners are focused on mastering their own specialized work domains. Their images of other professionals and the training received by them are often formed early in their experience base, and the images may be difficult to change. Dr. Young will have to work hard to communicate and demonstrate the value of his pharmacy knowledge to some practitioners and patients. The benefits of specialized knowledge will be lost if practitioners are unable to convey that knowledge to other professionals and patients. In teams, the benefits of specialization can be lost if team members are not aware of the specialized knowledge bases of their colleagues.

The challenges to teamwork caused by the specialization of team members can be understood in a broader sense with an analogy to work processes in the whole organization. Within organizations, differentiation is the degree to which individual employees are divided into different functional units of similar employees. Large healthcare delivery organizations have functional units of workers dealing with financial management, nutrition services, laboratory services, human resource management, nursing services, and information technology (IT), for example. When employees are grouped together because they do similar work, they are less connected to employees doing different work. Differentiation is a powerful driver of economy and productivity within the functional units, though, as employees within each unit can improve quality and efficiency by interacting and sharing ideas with other employees who “speak the same language.” For example, the IT unit workers share a common vocabulary and view of the “outside” or “non-IT” workplace, in the same way that nurses in a patient care unit share a common vocabulary and view of the “non-nursing” workplace.

Differentiation in organizations comes at a high cost to the whole organization, however, if activities of one unit need to be integrated or coordinated with those of other units. As a result, organizational researchers have long observed a positive correlation between the level of differentiation and the level of integration in effective organizations (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). Integration is the degree to which harmony of effort exists among different units. Integration of work processes is intensified when individual members of each unit know what the other units are doing. This requires interaction, sharing of information, and joint decision making about strategies and goals among the relevant units. For example, delivery of nutritious meals to hospital inpatients requires integration among nutrition services, nursing services, and admission and discharge services, at the least. In organizations, frequent communication and meetings, liaisons, cross-functional committees, cross-training, and co-leadership are examples of ways that different units use to share information and make joint decisions.

Differentiation among organizational units serves as a model for understanding differentiation within teams based on the professional identities of the team members. The various healthcare professionals are influenced by the roles, education, and values ingrained in the process of education, training, and socialization into their own profession—they are highly differentiated. If the team’s services require more than one profession, integration among the members of the different professions is needed to produce effective and efficient services.

One important tool for integration that can be applied to teams is cross-understanding. Cross-understanding as applied to groups of people is defined formally as “the extent to which group members have an accurate understanding of one another’s mental models” (Huber and Lewis, 2010, p. 7). Mental models affect the way that individuals make decisions and define and solve problems. Improved understanding of others’ mental models has 3 main effects. First, it improves the quality of communication. Cross-understanding allows group members to use terminology that is both known and respectful to other group members. Otherwise, messages can be perceived to be politically charged, technically incorrect, or confusing. Second, cross-understanding deepens and enriches one’s interpretation of another group member’s contribution. With cross-understanding, members are comfortable revealing their unique knowledge and beliefs, increasing the likelihood that the group “will discover or more fully understand relevant facts and cause-effect relationships” (Huber and Lewis, 2010, p. 11). Indeed, members in groups with high cross-understanding are more likely to consider information that is inconsistent with their initial preferences, and divergent or creative thinking is stimulated. This does not necessarily mean that mental models are abandoned or compromised, just that they become more comprehensive. Huber and Lewis (2010, p. 11) note the case of legislators with different ideologies who do not share the same mental model but who are better able to work together through cross-understanding. To some extent, professions might be compared to different political parties. Finally, integration is improved by cross-understanding through its effects on behaviors. Members are better able to predict the effect of their actions on others and make adjustments to their behavior in advance. They are more likely to “fill in the blanks” proactively and inform others when necessary, because they realize what information is needed by the other members. Members with cross-understanding are more likely to solicit information that others hold. For example, physicians who are familiar with the mental health counseling competencies of social workers will be more likely to ask the social workers about patients’ mental health needs or ask them to provide mental health services. Synergistic outcomes (outcomes not possible from the individual efforts of members) are more likely to emerge when members have cross-understanding.

Recent research on how perceptions of teamwork differ by profession underscores the need for improvement in cross-understanding. For example, 2 studies of the quality of communication and collaboration between nurses and physicians (one in general medical units of hospitals, one in operating rooms) found that nurses rated quality of communication and collaboration lower than physicians did (Carney et al, 2010; O’Leary et al, 2010). In both studies, physicians perceived that the quality of collaboration and communication was higher than nurses perceived it to be. Another study that included registered nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and physicians revealed that each profession rated its own collaborative behavior higher than members of other professions rated that profession’s collaborative behavior (Holden et al, 2010). The egoistic bias of individuals (the tendency to rate ourselves higher than others do) seems to be reflected in professions as well.

In summary, teams comprised of different professionals are highly differentiated by profession, which produces attitudes and behaviors that differ among team members. To produce high quality processes and outcomes, integration must be achieved. Cross-understanding is a means to create that integration.

HEALTHCARE OCCUPATIONS OR HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONS?

The reader will note that the term profession is used widely in this chapter and book. We refer to workers in healthcare delivery organizations as members of healthcare professions, rather than healthcare occupations. We find it unproductive for most purposes to distinguish between healthcare occupations and healthcare professions—although there are some exceptions.

These exceptions include, for example, discussing the historical evolution of nursing later in this chapter and explaining the weaker power of healthcare administrators compared to many healthcare professionals, in Chapter 5. For those purposes where a distinction is important, the basis for distinguishing professions from occupations usually is the characteristics of the occupation’s knowledge base and the attendant formal entry barriers to acquiring the knowledge base (Begun and Lippincott, 1993, pp. 40-41; Freidson, 2001, p. 127). Accordingly, Abbott (1988, p. 8) defines professions as “exclusive occupational groups applying somewhat abstract knowledge to particular cases.” Professions typically create exclusivity by controlling entry to the occupation. Entry to a profession requires advanced formal education in a specialized knowledge base, and education often is followed by required certification or licensure.

However, in general, the line between professions and occupations is highly arbitrary. Registered nurses (RNs) are required to have a specialized diploma or degree to qualify for a licensure examination. The specialized diploma or degree can take 2, 3, or 4 years beyond high school to complete. Common usage refers to RNs as healthcare professionals. Licensed practical nurses (LPNs) receive formal education of 1-2 years beyond high school and pass a licensure examination. Are LPNs professionals? Is the length of formal education the primary determinant of whether individuals in the field are professionals, or are other features associated with professions, such as the degree to which the knowledge base is abstract, equally important to consider? Such questions illustrate that the term profession is “an intrinsically ambiguous, multifaceted folk concept” that varies in meaning across cultures and indeed does not exist in some cultures (Freidson, 1994, p. 25). Among individuals working in healthcare teams, focus on the term can create distance in conversations and negotiations if one team member is referred to as a professional, and another team member is not. Avoiding making the distinction between professional and non-professional is appropriate for most purposes in discussing and providing team-based health care.

WHO’S A “DOCTOR”?

Marta Daingerfield had recently completed her Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree and was anxious to start off on the right foot in building professional relationships with her associates. Tomorrow she is due to meet her new colleagues on the hospital-wide infection control committee. Will she be introduced as “Doctor” Daingerfield? If not, should she correct the speaker? Should she introduce herself to others as “Doctor”? That certainly was her expectation when she enrolled in the DNP Program, one that was reinforced in her education. How would the “real” doctors respond to that? What if they ask her where she attended medical school?

An issue related to the use of the term profession is the use of the term doctor. Both terms vary in meaning over time and across settings. Historically in the United States, doctor has been used to refer to physicians (in healthcare usage) and to those attaining a “doctoral” or “doctorate” degree from a university (in general usage). Over time, several health professions have elevated their educational preparation to a level defined by that profession as a “doctoral” level, as described in the earlier vignette about 2 pharmacists. Recently, for example, the doctorate of nursing practice has been initiated as the most advanced degree for clinical nurses. Pharmacy and physical therapy, among other health professions, issue practice degrees labeled doctorate by the profession. Despite that, many pharmacists and physical therapists holding the doctorate degree often do not refer to themselves as doctor.

Individual administrators and clinicians will evolve different positions on use of the appellation, both as it applies to themselves (if they hold a doctorate degree) and to others. Many physicians use the term doctor only to refer to other physicians. One administrator who is a colleague of the authors only uses first names in talking to clinicians and to other administrators, to imply that “we are all equals.” Part of relating to other professionals effectively is to understand how the other professional prefers to use the term “doctor,” and to consciously make the decision to respect that individual’s decision or not. Often, the decision will have implications for the extent to which the other professional feels valued as a team member.

ROLES, EDUCATION, AND VALUES OF FIVE HEALTH PROFESSIONS

The gray areas discussed above—sensitivity over whom to label professional and whom to call doctor—illustrate the importance of knowing the recent history and intra-professional norms of other professions. In support of practitioners learning about each other’s professions, we next present a rudimentary knowledge base for cross-understanding among health professions. Key differentiators among professionals that are relevant to teamwork are the typical roles, education, and values of the professions. We compare 5 healthcare professions or categories of healthcare professions. The 5 professions—medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work, and healthcare administration—are the largest in number of the healthcare professionals involved in interprofessional teamwork in healthcare delivery. Literally, over 100 other professions participate in interprofessional teamwork in healthcare, and we make reference to several professions in addition to those we focus on primarily. Recent changes in the 5 professions that affect their involvement in interprofessional teams also are presented.

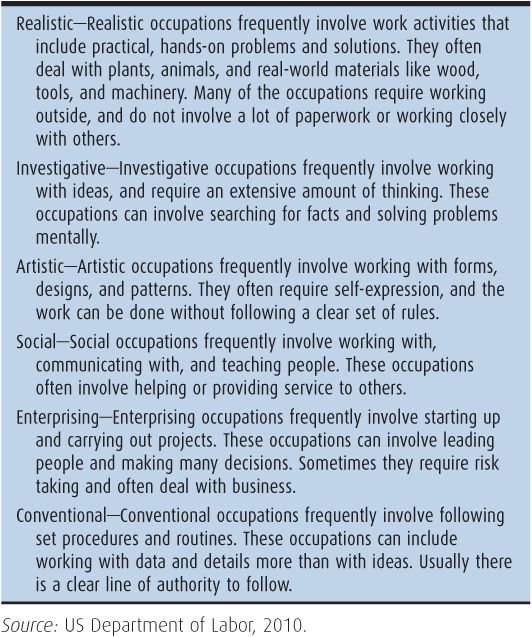

Values of individuals refer to their preferences regarding appropriate courses of action or outcomes. Professional values are inculcated through education and socialization into the professions. In healthcare professional education, the values generally are assumed rather than explored or challenged (Sharpe and Curran, 2011, p. 76). Below, we comment on the primary values of the 5 professions. In addition, we present information on a category of characteristics of occupations labeled interests by the Occupational Information Network program (O*NET) of the US Department of Labor (US Department of Labor, 2010). The O*NET program compiles information on US occupations and professions by randomly sampling incumbent workers in different occupational categories and surveying them with a standardized questionnaire. A benefit of the O*NET program is that it provides a common set of categories and an empirical basis for observations about the similarities and differences among health professions. The O*NET Program defines interests as preferences in a work environment, and the 6 preferences or interests derive from a history of research that relates personality types to work environments (Holland, 1997). The research established that certain personality types are attracted to and thrive in certain types of occupations and professions. The 6 interests are: Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional. Realistic interests are quite practical and hands-on. Investigative ones require thinking and solving problems. A preference for self-expression, often without strict rules, is labeled Artistic. Social interests involve working with others and helping them. Enterprising interests entail leading and making decision and, often, taking risks. Conventional interests reflect a preference for following set procedures and rules. Table 3–1 displays more detailed definitions of the 6 interests.

Occupations are assigned a profile of interests, with the primary interest listed first. The fairly elaborate methodology for constructing the profiles is described by researchers (Rounds et al, 1999; Rounds et al, 2008). Occupations were categorized by a combination of empirical analyses and judgment by trained raters, resulting in each occupation being characterized by a profile of 1-3 interests. A 3-interest profile, which is assigned in most cases, means that the first interest is most descriptive of the occupation, the second interest is less descriptive but salient, and the third interest is even less descriptive but still salient. A 2-interest classification (the case for social work below) means that the first interest is most descriptive, the second interest is less descriptive but salient, and none of the other interests is salient.

The following descriptions of professions include generalizations that may not apply to particular individuals in the professional roles. Many of the generalizations have an empirical anchoring in occupational research, such as the Department of Labor survey program, which is cited. Other generalizations are based on experiences of the authors or others. To avoid stereotyping (assigning characteristics to all members of a category that apply only to some members), there is no substitute for learning about the particular individuals on one’s team. The individuals may differ quite substantially from the generalized depictions presented here.

PHYSICIANS

Every weekday at 8 a.m., Jane Daggett, MD, begins seeing patients in her clinic. Dr. Daggett is a general internist. Her patients are all adults. Patients are scheduled for 15-minute or 30-minute visits or, occasionally, for a 45-minute visit. The standard time slot is 15 minutes, but Dr. Daggett requests longer visits for patients with greater need, for example, older patients and patients who have several complicated medical problems. The patients are brought to one of Dr. Daggett’s 2 examination rooms by Cindy Wolff, CMA (Certified Medical Assistant), who confirms the patient’s reason for seeing Dr. Daggett, measures the patient’s weight, takes his or her blood pressure, and updates the patient’s medication list in the electronic health record. Dr. Daggett then sees the patient, taking his or her medical history, doing a physical examination as relevant to the patient’s symptoms or disease, and planning treatment or changes in treatment such as changes in medication doses. Sometimes she performs a joint injection (for example, injecting medication into a patient’s knee), but, as a general internist, she does not do many procedures.

Dr. Daggett finishes her morning schedule officially at 11:30 a.m. However, her last patient for the morning usually leaves 15-20 minutes after this time. If she has not already finished writing notes in the electronic records of the patients she has seen, she completes her notes then. She also answers telephone calls from patients, responds to secure e-mail messages sent by patients, and reviews laboratory results that are delivered to her in the electronic record, where they are flagged so that she is alerted to the arrival of the results.

She usually eats lunch with other physicians in the cafeteria from about 12:30 to 1:00, then returning to the clinic to continue answering telephone messages, writing referral requests for patients who need specialist consultation, and doing other tasks generated by her interactions with patients that morning or during the previous few days.

Sometimes there is a midday meeting to attend, perhaps an Internal Medicine Department meeting or a quality improvement (QI) project meeting. Dr. Daggett has a particular interest in the management of diabetes and participates in a long-term project to improve the processes used in the clinic for managing patients with diabetes. Other members of the QI project team are a nurse practitioner (NP) who specializes in diabetes care, 2 CMAs, a family physician, and a staff person from the QI office, who manages the project and collects and analyzes data for the team.

In the afternoon, from 1:30 to 4:30 p.m., Dr. Daggett again sees scheduled patients. Occasionally an NP in the department will knock on Dr. Daggett’s door and ask a question or ask Dr. Daggett to see a patient for a quick consultation. At the end of the day, Dr. Daggett returns to writing notes in the electronic record, filling in disability forms or other forms requested by patients, and carrying out other work that flows from her direct contacts with patients.

In total, Dr. Daggett sees about 20 patients each day or about 100 per week. Earlier in her career, she began each day in the hospital, rounding on 2-6 patients whom she had admitted to the hospital. She then would drive to the clinic to see scheduled patients. Her hours in the clinic were fewer then. In recent years, she has stopped doing hospital work. In contrast, some of her internal medicine colleagues have stopped doing work in the clinic and see patients only in the hospital, that is, they have become hospitalists.

Roles

Roles

As illustrated by the vignette about Dr. Daggett, physicians diagnose illnesses, and prescribe and administer treatment for people suffering from injury or disease. They examine patients, obtain medical histories, order and interpret diagnostic tests, prescribe drugs, perform surgery, and manage chronic disease. They also counsel patients on diet, hygiene, preventive health care, and mental health problems. There are 2 types of physicians: those with a Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree and those with a Doctor of Osteopathy (DO) degree, with MDs being the vast majority (over 90% of physicians in the United States). MDs attend medical school; DOs attend osteopathic schools. In osteopathy there is a historical preference for understanding and using manual therapy, or manipulation, but similarities between the training of MDs and DOs far outweigh the differences (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2012, p. 75).

In 2007, there were about 941,000 physicians in the United States, of which 67% were graduates from a US school of medicine (conferring the MD degree), 7% were graduates from US school of osteopathy (conferring DO degrees), and 26% were graduates of foreign medical schools (American Medical Association, 2010; American Osteopathic Association, 2010). Thus, a large number of physicians in the United States were trained outside the United States. Foreign-trained physicians must pass the US medical licensing board examinations, and complete internships and residencies in the United States before being licensed to practice medicine.

Physicians are highly specialized. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) encompasses 24 major specialties with certification in 145 specialties and subspecialties (ABMS, 2012). The 5 largest specialties are internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and anesthesiology (US Census Bureau, 2011, p. 115). The continued development of biomedical knowledge as well as new specializations and new arenas for care giving, such as hospitalist care, spawn more and more specialization and subspecialization. For example, internal medicine approved 4 new subspecialties in the 2006-2010 period—transplant hepatology, sleep medicine, hospital and palliative medicine, and advanced heart failure and transplant cardiology (Cassel and Reuben, 2011). As noted below in a comparison of internal medicine and surgery, specific specialties in medicine attract different personality types, creating differences by specialty not only in knowledge base and approach to medical problems but also in contributions to team processes.

Many physicians—chiefly family physicians, general internists, pediatricians, obstetrician/gynecologists, and psychiatrists—work in small private offices or clinics, assisted by a small staff of nurses, certified medical assistants, and administrative personnel. Increasingly, though, physicians are practicing in groups or are employed by large healthcare organizations. Physicians working in group practices or as employees of a healthcare organization often work with other physicians, nurses, and other professionals to coordinate care for a number of patients. They are less independent than solo practitioners, whose numbers are steadily decreasing. Surgeons and anesthesiologists usually work in hospitals or in surgical outpatient centers; they also conduct office visits to evaluate patients for surgery and do follow-up surgical visits. Many physicians work long, irregular hours. Physicians often travel between office and hospital to care for their patients, although this is rapidly decreasing with the strong growth of hospital-based medicine. While on call (available at short notice), a physician will deal with many patients’ concerns over the phone and make emergency visits to hospitals or nursing homes.

Some 60,000 physician assistants (PAs) work in the United States, practicing medicine under the direct supervision of physicians. Studies conclude that the work domain of PAs overlaps with approximately 80% of the scope of work of primary care physicians (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2012, p. 77).

Education

Education

Physicians go through an extended period of formal education and training. In the United States, physicians typically complete a bachelor’s (undergraduate) degree followed by 4 years of medical school and then residency training in a particular specialty for 3-7 years. Residency training is sometimes followed by a fellowship of 1-3 years in a subspecialty. Radiologists, for example, typically have 5 years of training beyond medical school, general surgeons have 5 years, cardiac surgeons have 7 years, and family physicians have 3 years of training.

Physicians apply for licensure at the state level in the United States, with requirements determined by each state. Requirements that are common across the states include passing the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) and training beyond medical school of at least 1 year. As mentioned above, foreign-trained physicians wanting to practice in the United States must pass the USMLE and then must complete residency training at a US institution, regardless of their years of experience abroad. Those wanting to specialize also must repeat specialty training such as fellowships. For many foreign-trained physicians, the path to practice in the United States is long and difficult.

An additional credential held by most physicians is specialty board certification. About 75% of physicians are board-certified (Young et al, 2011). Board certification is not required for state licensure, but many hospital medical staffs require board certification for medical staff membership and privileges to admit patients to the hospital. A physician becomes board-certified by passing an examination conducted by a certifying organization, such as the American Board of Surgery.

Physician assistant education averages 27 months, with most programs requiring a baccalaureate degree as a prerequisite and granting a master’s degree. To be eligible for licensure in most states, PAs must graduate from an accredited program and pass a national certifying examination (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 2012, p. 77).

Values

Values

Department of Labor sources (US Department of Labor, 2012) state that people who wish to become physicians should be detail oriented, have good communication skills, and have patience to work with those who need special attention. Empathy for patients and their families is important for compassionate care. Dexterity with their hands and physical stamina also are noted as important qualities for clinical care. Leadership and organizational skills help with practice management. Finally, problem-solving skills are important in making diagnoses and administering appropriate treatment. Medical education has been described by many as rigorous and competitive. Thus, the “prototypical medical school student is extremely bright and achievement-oriented, and astute at adapting to the environmental cues necessary to achieve success” (Garman et al, 2006, p. 832). Prospective physicians must be willing to study throughout their careers to keep up with medical advances.

In practicing health care, physicians value excellence in diagnosis and treatment, including drug treatment and surgery, and achieving cure of the patient’s disease (or minimizing symptoms). The focus on cure and a push for excellence underlie some of the behavior that other professionals may find intimidating or too forceful. Other key distinguishing values and interests of physicians that affect healthcare teamwork include the following:

1. Physicians are ordinarily concerned about costs of their services only as a secondary issue. Accurate diagnosis and cure for the patient are to be pursued regardless of cost, within reason as judged by the physician and patient, not an insurance company employee or healthcare administrator.

2. Physicians are very independent. They expect to have clinical decision-making autonomy. They do not automatically follow hierarchical commands.

3. Physicians expect problems to have solutions. Problems are not to be discussed ad nauseam. Work is expected to proceed at a fast pace.

4. Physicians expect high social status. They aspire to achieve the esteem of patients, peers, and the local community.

5. Physicians respect scientific evidence. They look for objective evidence to make patient-related decisions.

Another perspective on physicians’ values is provided by the occupational database, O*NET, described earlier. Consistent with the long educational stint served by physicians, the top-ranked interest of physicians is labeled as Investigative. People with investigative interests enjoy working with ideas and thinking more than performing physical activity. They like to search for facts and solve problems mentally rather than to persuade or lead people (US Department of Labor, 2012).

Different medical specialties attract different personality types. Comparing 2 specialties with quite different work responsibilities, surgery and internal medicine, illustrates the point. Both surgeons and internists have the same trio of top interests: Investigative, Realistic, and Social. Both have Investigative as their top interest. For surgeons, the second-ranked interest is Realistic. Individuals with realistic interest enjoy practical, hands-on problems and solutions. For internists, on the other hand, the second-ranked interest is Social. Social occupations involve working with, communicating with, and teaching people. Table 3–2 displays the interest profile of internists and surgeons, along with the other professions examined in the following sections of this chapter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree