As discussed in Chapter 12 on team sponsors, whole teams generally are evaluated on the basis of: (1) goal achievement, and (2) whether the teams have the characteristics of effective teams. In Chapter 12, an example of a whole-team evaluation process was presented in the case of an Orthopedic Surgery Department, whose leader and sponsor reviewed the team based on the goals of the orthopedic surgery team and the 32 characteristics of effective teams. Goals of clinical teams generally include all of the Institute of Medicine aims (safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity), while other goals are specific to the task at hand. Goals of management teams vary depending on the assigned task.

In this chapter, we focus on the highlighted dimensions of Table 13–1—evaluation of the teamwork competencies of individuals and the characteristics of effective whole teams. These topics generalize across individuals and teams, independent of the goals of the specific individual or team.

INFORMATION FOR INDIVIDUAL AND TEAM EVALUATION

Types of Information

Types of Information

A wide variety of information can serve as a basis for individual and team evaluation. Commonly, team leaders develop judgments about individual teamwork competencies and whole-team characteristics by observing interactions and behaviors in the team and obtaining information about impact on patients, colleagues, coworkers, and the overall organization.

Qualitative information comes from observation of qualities that cannot be measured numerically; this information may contain a high degree of subjectivity. Qualitative information relevant to individual teamwork competencies and whole-team effectiveness may come from praise or complaints from patients or fellow teammates, observations by team leaders of accomplishments or problems with individuals or teams, or sudden changes in team member behavior for the better or worse, for example. As a source of qualitative information, direct observation is far superior to secondhand reports, and reports from trusted sources are superior to reports from sources of unknown reliability.

Quantitative information measures quantities or other measurable properties with metrics. Commonly, quantitative information comes from ratings by supervisors, team leaders, sponsors, members of teams, and those served by teams. Quantitative information can be collected in a systematic, quantitative, and regular manner in order to monitor individual teamwork competency and overall team effectiveness. Instruments to collect quantitative information can vary widely in reliability and validity, as discussed later. Use of measurement instruments with established high reliability and validity are important in maintaining the legitimacy and utility of evaluation efforts.

Type and frequency of collection of information depend on the nature of the feedback and the nature of the team, particularly its permanence and stability of membership. Many permanent teams review indicators of progress toward goals at their regularly scheduled meetings; for example, a clinical team may monitor patient satisfaction measures as they are updated monthly. Outside experts or consultants are useful in providing another perspective. Stable teams should strive to have regularly scheduled evaluations of team members and the whole team as a basis for improvement. Evaluation of individual competencies and team characteristics in template teams and knotworks is likely to occur less regularly and less frequently, but in many cases it can be helpful to individual team member growth and development. Team members who work solely on one team are likely to have teamwork contributions regularly assessed by both qualitative and quantitative means as part of overall job performance evaluation. At the other extreme, team members who work on multiple teams can benefit from collation of information on their performance on the multiple teams, typically by a supervisor or sponsor who has formal authority over the multiple teams. Or, individuals can request performance feedback for their self-development.

Many individuals resist evaluation of their performance by others, as discussed later. As a result, some researchers advise working on whole-team assessment first, then individual assessment of each other’s strengths and weaknesses. The rationale is that it is easier to critique the team than individuals in terms of emotional comfort (Heinemann, 2002, p. 14). The important step is having team members “step outside the team” to objectively evaluate its performance. With that preparation, members are able to evaluate their own performance more objectively and effectively.

Sources of Information

Sources of Information

Evaluative information for whole teams and for individual team members typically is collated and delivered by the team leader or sponsor, or multiple team leaders or sponsors if the individual is on multiple teams. Often it is collated from multiple sources, and sources are kept anonymous if possible.

Multirater feedback comes from more than one source, with the traditional one source being the team leader. With 360-degree feedback, information is solicited from those who are the individual’s supervisors, peers, subordinates, and patients or other clients. In some cases, a list of knowledgeable raters can be codeveloped by the individual and the team leader. An advantage of 360-degree or multirater evaluation is the dilution of any one individual evaluator’s bias. As noted earlier, typically the source of feedback is not identified, if possible. Performance appraisers give poor performers higher ratings when they give face-to-face feedback as compared to anonymous written feedback (Thompson, 2011, p. 64).

Human imperfections and the realities of implementation limit the utility of multirater evaluation, however. Individuals may collude to give high ratings to each other; raters may fear retaliation for honest comments if anonymity is compromised; team members unpopular for reasons other than performance can suffer; and team members may not understand the “big picture” (Thompson, 2011, pp. 54, 61-65). Inflation bias arises from empathic buffering and fear of conflict. Empathic buffering is reluctance to transmit bad news to a poorly performing teammate, which makes the bearer of news feel badly as well. Preference to avoid conflict is particularly acute if the other party is expected to respond defensively. Homogeneity bias means that appraisers rate others who are similar to themselves more favorably than those who are different from them. Halo bias holds that when a rater knows one positive (or negative) fact about someone, the rater tends to perceive newly acquired information about that person as conforming to the perceptions acquired earlier.

Determining who should participate in evaluating other individuals and whole teams is important. Core members who have sufficient knowledge of each other and team characteristics should be included. If peripheral members are not included, they may feel marginalized. If peripheral members do not possess enough information to make accurate judgments, though, their input may bias the information. Other individuals may neglect to provide input because they devalue it; requiring responses, however, can create animosity and biased responses as well. The more diverse the team, the greater the need for working on design of evaluation instruments, as members will vary by reading level, comfort with questionnaires, and comfort with different formats. Team members should actively participate in the design of evaluation instruments.

Confidentiality of sources is an important issue as well. Raters will be concerned about whether their responses will identify them (as a result of specific information provided in their response) and whether supervisors of the person being rated will have access to their identities. In many cases, it is preferable that supervisors have access to identities of raters, in order to forestall vindictive and unconstructive comments or ratings that a rater may otherwise direct at a personal enemy. If raters are totally anonymous (to both the person being rated and that person’s supervisor), enemies of the reviewed person (or those who covet the reviewed person’s job) may distort their reports, criticize by innuendo, or simply invent false reports—all without fear of being held accountable. A supervisor may be able to filter such comments if he or she knows the source.

EVALUATING INDIVIDUAL TEAMWORK COMPETENCIES

Robert Platt, RN, MSN, a clinical nurse specialist in the oncology unit at Gibbs Hospital, prided himself on being an expert clinician. He had been an “A” student in nursing school, and his preceptors in school and subsequent employers praised his knowledge base as well as his comfortable and engaging manner with patients and their family members. Mr. Platt was a fervent believer in patient rights and patient involvement. For example, frequently he would query patients and family members for their feelings about therapies, discharge dates, and other issues, sometimes urging them to question the recommendations made by other clinicians.

Mr. Platt worked on 3 different clinical teams comprised of combinations of oncologists, nurses, pharmacists, and others. He carried his passion for patient rights into case discussions in the 3 clinical teams he worked with. He frequently spoke about patient rights with great energy and at length. One team, in particular, challenged his opinions about patient rights. That team included a philosophical nemesis of Mr. Platt’s, Terry Briese, MD. Dr. Briese was famous for goading other clinicians into arguments about patient involvement, with Dr. Briese professing that the less patients know, the better. The arguments often interfered with team discussions and team progress. Mr. Platt felt that sometimes Dr. Briese just wanted attention and that his beliefs weren’t really as extreme as he pretended. The team leader showed little interest in breaking up the arguments and never had counseled Mr. Platt or Dr. Briese about their behavior in meetings.

Healthcare professionals are educated and socialized into individualistic professions, where personal knowledge and expertise in clinical or management practice is the main barometer of their achievement (see Chapter 3). Some professions, such as healthcare administration and pharmacy, build more teamwork into their training and education than other professions do. But individual performance review dominates the educational, training, and work experience of virtually all healthcare professionals. The growth of team-based clinical care and the increasing use of cross-functional teams in management are challenging this tradition, both in formal performance reviews by employers and in evaluations used by team leaders and members to improve their teams. It is becoming more common that job performance assessments of individuals include measures of contributions to team processes and outcomes. Such assessments become part of an employee’s human resources file and are used in promotion and merit review decisions. For individuals employed full time on one team, assessments of contributions to the team can be a significant component of overall job performance reviews. For individuals working on more than one team, supervisors can collate performance feedback from the different teams to be used in job performance reviews. Even if such evaluations are not part of an employee performance review system, team leaders can use individual evaluations for developing and training purposes on their teams.

Why Evaluate Individual Teamwork Competencies?

Why Evaluate Individual Teamwork Competencies?

The obvious reason to evaluate individual teamwork competencies is to provide a baseline for improvement and development, particularly in light of the inadequate training on teamwork that most professionals receive in their education and socialization. Leaders and sponsors of teams who are interested in improving team performance need to examine individual competencies as a root cause of team effectiveness and ineffectiveness. Team leaders driven to exercise the competency to assure that the team can carry out team-level operations effectively (see Table 8–3 in Chapter 8) can benefit from assessing individual member’s teamwork competencies. In Chapter 7, we also pointed out that a basic competency of all team members is to be able to hold other team members responsible for their contributions (in a respectful way). Individual team members need to be able to evaluate others in order to fulfill their commitment to the team as well.

Yet many team members, like Mr. Platt and Dr. Briese and other members of the oncology team in the preceding vignette, receive little evaluative feedback about their teamwork competencies. Team sponsors, leaders, and members often are content to function in the absence of feedback.

Resistance to Individual Evaluation

The lack of individual evaluation of teamwork contribution on the oncology team in the preceding vignette is not surprising. Individual evaluation is seriously underutilized in healthcare teams, for several reasons. First, individuals in general are uncomfortable giving negative feedback to others. For this reason, individual team members often give (and receive) either no feedback or only positive feedback. They receive little in the way of constructive suggestions for improvement. Second, team leaders in healthcare frequently lack training and experience in individual performance evaluation, which exacerbates any natural inclination to avoid conflict or avoid giving bad news to others. Third, most individuals, including team leaders, do not like to be evaluated, and they assume the same for others. Projection of this bias decreases the likelihood of feedback provision even more. Another interesting assumption that works against the desire to evaluate is the extrinsic incentives bias, which states that people believe that others are more motivated by extrinsic factors (for example, pay and status) and less motivated by intrinsic factors (for example, personal accomplishment and learning new skills). People motivated by extrinsic factors are more likely to devalue the opportunity to grow, learn, and develop provided by feedback—they are satisfied with extrinsic rewards (Thompson, 2011, pp. 61-62). Believing this, a team leader is less likely to think that feedback will improve the behavior of others.

In addition, receiving feedback is problematic for many. Thus attention needs to be paid to improving team members’ competency in hearing and acting on feedback. Several individual biases interfere with our ability to receive feedback accurately (Thompson, 2011, pp. 65-67). Egocentric bias (we give ourselves more credit than others do) explains why people feel underappreciated, no matter how positive the evaluation they receive. Interestingly, efforts to counter egocentric bias, for example, by praising the efforts of others, can backfire by decreasing motivation. Positive feedback can also decrease intrinsic motivation relative to extrinsic motivation, particularly if extrinsic rewards follow from the positive feedback. For example payfor-performance tends to make people less enthusiastic about their work. Individual response to feedback is affected by comparison to others, too, such that positive feedback is less meaningful if everyone else also receives it. Sharing information about team averages and variation helps individuals make accurate comparisons to others. Finally, individuals accept feedback better if they think that the information collection process and the criteria for performance are equitable and fair. A transparent and well-vetted evaluation process leads to greater acceptance of the results of that process.

Overcoming Resistance to Individual Evaluation

Teams should strive to highlight the opportunity to provide feedback to others as a sign of commitment to the team and a sign of respect for the contribution of other members. To avoid giving respectful feedback is to hamper team effectiveness. It takes courage to call other members on behaviors that might be harming team progress, particularly if one has a positive relationship with the other member that may be affected. Again, though, if team outcomes are important, team members need to accept the possibility that personal friendships may be negatively affected if they give feedback to a personal friend. Feedback from peers is particularly powerful in promoting change on interprofessional teams. As one organizational consultant puts it, “No policy or system approaches the fear of letting down respected teammates to improve performance” (Lencioni, 2002, p. 213). Leaders and team members need to remember that the team is more important than any individual contributor, and that a responsibility of leadership is to do the tough work of holding individuals accountable if they are dragging down team performance.

Individual Feedback as a Two-Way Learning Process

Individual Feedback as a Two-Way Learning Process

Individual feedback should be an initial step in an ongoing process of learning between the provider of feedback and the receiver. This is not obvious from use of the term feedback, which formally can connote a one-time, one-way provision of information from one party to another. A first step in effective evaluation is defining performance feedback as a 2-way process. The provider of feedback is responsible for listening to the response of the receiver and adjusting the feedback accordingly, rather than imposing it on the receiver. Feedback is a joint learning process, then. In productive feedback sessions, both parties learn something.

Team leaders need to make sure that individual members’ strengths and weaknesses are evaluated and the feedback is shared with them, whether it is done directly by the leader, sponsor, or a person delegated by the team leader. Such information will help the individual to improve weak competencies and sustain strong ones. It is not only good for the individual, but it enhances the team performance as well. In the earlier vignette, the oncology team is suffering because the leader is not providing individual feedback, and Mr. Platt and Dr. Briese are not contributing optimally to their team. Neither of the team members is providing respectful feedback to each other on their performance, either. Mr. Platt clearly was in need of feedback on his performance on the oncology team. His behavior was affecting team performance negatively, but his team leader was failing to take action. The team leader needs to understand Mr. Platt’s position, as well. Hearing Mr. Platt’s rationale for patient involvement might make his outbursts seem less baffling to understand and easier to address. In addition, the team leader needs to provide feedback to Dr. Briese. He needs a better understanding of Dr. Briese’s reasoning and behavior in order to do so.

Instruments for Individual Evaluation of Teamwork Competencies

Instruments for Individual Evaluation of Teamwork Competencies

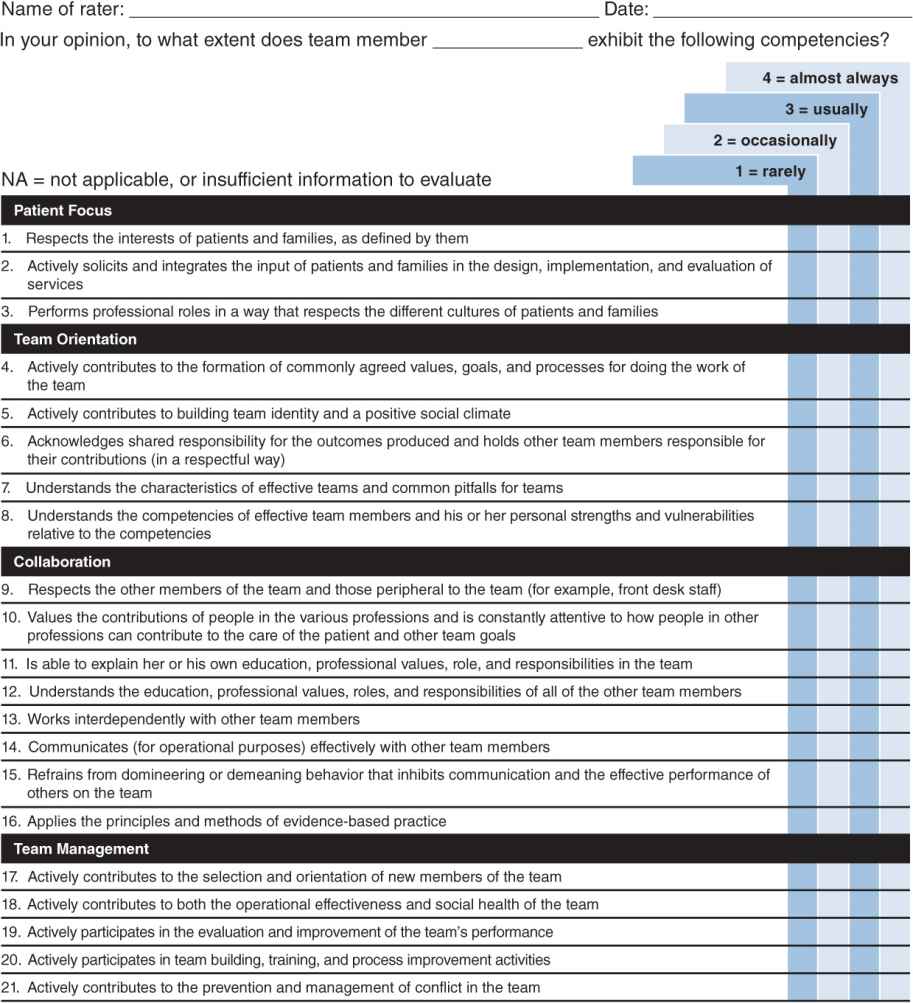

Individual feedback on teamwork competencies often is driven by specific incidents, such as the arguments between Mr. Platt and Dr. Briese in the vignette, and is given in the form of qualitative information. More formally, individuals can be rated by leaders or multiple raters, at regular intervals, on the range of individual member teamwork competencies. The instrument depicted in Figure 13–1 utilizes the list of teamwork competencies outlined in this book (see Chapter 7). Any list that covers the range of key competencies could be used, such as those models promulgated by the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC, 2010) and the Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (IECEP, 2011), discussed in Chapter 7. Or, a subset of competencies that are particularly important or troublesome for a team could be targeted, such as the 8 competencies covering collaboration listed in Figure 13–1. Several guidelines for delivering evaluative information to individuals follow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree