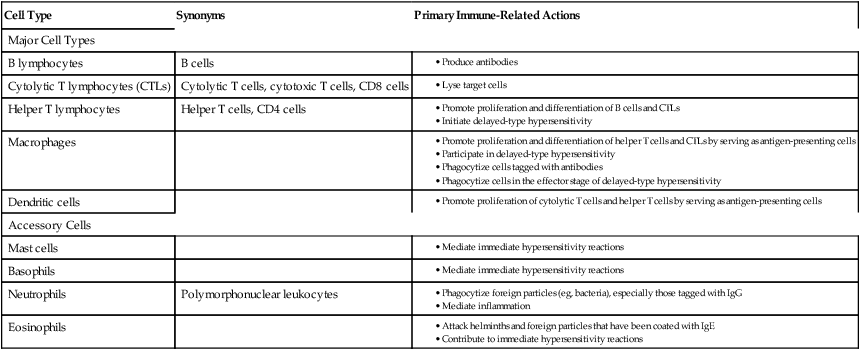

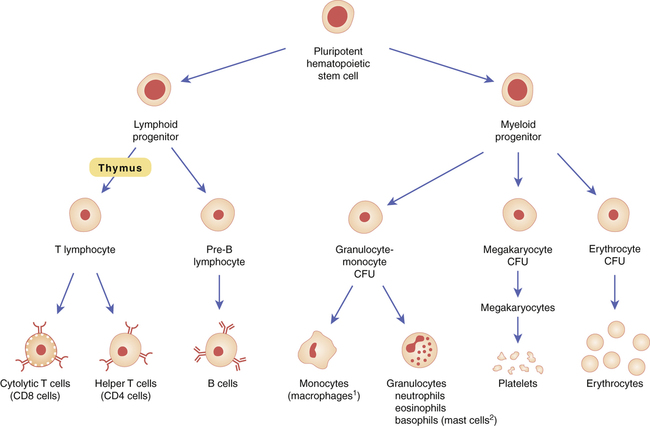

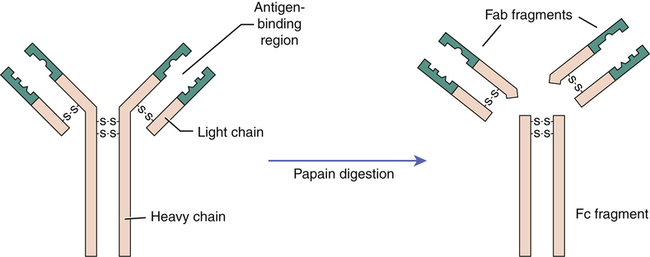

CHAPTER 67 Immune responses are mediated by several types of cells, some of which play a bigger role than others. The major actors are the lymphocytes (B cells, cytolytic T cells, helper T cells), macrophages, and dendritic cells. Accessory cells include neutrophils and basophils. With the exception of some dendritic cells, all of the cells involved in the immune response arise from pluripotent stem cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 67–1) and, for at least part of their life cycle, circulate in the blood. Defining characteristics of individual immune system cells are summarized in Table 67–1. TABLE 67–1 These cells mediate immediate hypersensitivity reactions. Mast cells, which are derived from basophils, are concentrated in the skin and other soft tissues. Basophils circulate in the blood. Both cell types release histamine, heparin, and other compounds that cause the symptoms of immediate hypersensitivity. Release of these mediators is triggered when an antigen binds to antibodies on the cell surface. The role of mast cells and basophils in allergic reactions is discussed further in Chapter 70 (Antihistamines). All antibodies are composed of units that have the same basic structure. As shown in Figure 67–2, antibodies have four chains: two heavy chains and two light chains. Disulfide bridges connect the four chains to form a unit. Each heavy chain and each light chain has two regions, one in which the sequence of amino acids is constant and one in which the sequence is highly variable. The variable regions form the antigen-binding site. There are five classes of antibodies (immunoglobulins), known as IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM. All are constructed from the same basic parts just described. However, the heavy chains differ for each class. Primary functions of the five classes are summarized in Table 67–2. TABLE 67–2

Review of the immune system

Introduction to the immune system

Introduction to cells of the immune system

Cell Type

Synonyms

Primary Immune-Related Actions

Major Cell Types

B lymphocytes

B cells

Cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTLs)

Cytolytic T cells, cytotoxic T cells, CD8 cells

Helper T lymphocytes

Helper T cells, CD4 cells

Macrophages

Dendritic cells

Accessory Cells

Mast cells

Basophils

Neutrophils

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Eosinophils

Maturation of blood cells.

Maturation of blood cells.

With the exception of platelets and erythrocytes, all of the mature blood cells shown participate in immune responses. However, only cells of lymphoid origin (cytolytic T cells, helper T cells, B cells) possess receptors that can recognize specific antigens. (CFU = colony-forming unit.)

1Monocytes that have moved into tissues are called macrophages.

2Basophils that have moved into tissues are called mast cells.

Mast cells and basophils.

Antibodies

Antibody structure.

Antibody structure.

The basic antibody structure depicting heavy and light chains is shown on the left. Variable regions of the heavy and light chains, which form the antigen-binding site, appear in green. As shown on the right, papain digestion of antibodies produces two types of fragments: Fab fragments, which retain the ability to bind antigen, and Fc fragments, which do not bind antigen and tend to crystallize in the test tube.