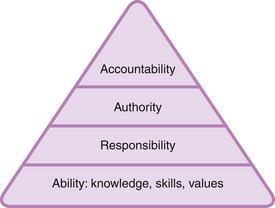

Chapter 2 For the many busy nursing and midwifery practitioners, having the additional role of practice educator to students adds to the role strain (Allan et al 2011, Dolan 2003, Phillips et al 1993, 2000). Teaching and assessing are add-on activities and the adjuncts that are attended to when time permits. Practitioners who are in this unenviable position frequently feel unhappy that the supervision and support of students cannot be made more of a priority. What students learn may be left to chance. Positive assessment decisions about performance may have been made without the concrete evidence of having observed the student in action (White et al 1994). Practitioners may, or may not, be aware of the many legal and ethical ramifications of making assessment decisions in this manner, and for providing an insufficient level of supervision and support for learners. • What are practice educators responsible and accountable for? • Who are practice educators responsible and accountable to? This latter question is considered in conjunction with the role, responsibilities and accountability for student learning and assessment. Very frequently, a practitioner who is the mentor to a student is also required to assess the student (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) 2009a, Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2008a). Some of the dilemmas of this dual role are also explored. As the nursing and midwifery professions and the professions regulated by the Health and Care Professions Council strive for professional status and self-regulation, the term ‘accountability’ has assumed increasing importance (Allen & Dennis 2010, Ormerod 1993, Emerton 1992, Bergman 1981). Accountability as an integral part of health care practice in the UK has been high on the agenda of the NMC and the HCPC. The position taken by the NMC and the HCPC will be discussed later. Health care professionals are required to consider and observe – often simultaneously – ethical, psychological, ethnic and human rights aspects in the discharge of their duties. Society places a high value on the health care professions. The confidence and trust in which health care professionals are held are measures of the special relationship between them and the vulnerable patients and clients in their care. In the UK, the NMC was established under the Nurses and Midwives Order 2001 (NMC 2001, SI 2002 No. 253) and came into being in April 2002. This Act set out the constitution, establishment and functions of the NMC. The responsibility for the regulation of nursing, midwifery and specialist community public health nurses is vested with the NMC. The HCPC was established under the Health Professions Order 2001 (HCPC 2001, SI 2002 No. 254) and came into force in February 2002. The primary mandate of the NMC and the HCPC is to safeguard the health and well-being of the general public. This is done by keeping a register of all their registrants and ensuring they are fit to practise. The NMC and HCPC also set the standards for the education, training and conduct of those on the register. In all their work, the NMC and HCPC act in collaboration with others, including statutory and professional bodies, education providers, employers and education commissioners. In 2002, the NMC published its first code of professional conduct. This is now called The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives (NMC 2008b). Likewise, the HCPC published standards of conduct, performance and ethics for its registrants in 2003 when their register opened that year. An updated edition was published in 2008 (HCPC 2008). In addition to safeguarding standards and principles of practice for patients and clients, the Standards are intended to assist individual practitioners by an expression of the components of acceptable professional practice and related ethical considerations. The Standards set out the responsibilities and accountability of the registered practitioner and are the basis of the regulatory framework. They stress the personal accountability of each practitioner for her/his own practice, and that accountability may not be delegated or transferred to another person. The Standards expressly require that the interests of patients and clients should take precedence over all other considerations. Accountability becomes strikingly real when set in the context of clinical situations where professional knowledge and competence are exercised when caring for the diverse range of patients and clients. It is evident that professional accountability in the health care professions is a complex matter. It includes ‘ethical, societal and public duty and protective elements for patients and clients’ (Royal College of Nursing (RCN) 1990:4). There are many questions that can be asked about accountability in general. You may wish to carry out Activity 2.1 before progressing with an exploration of the concept of accountability. It is not possible to enter into an extensive philosophical discussion of the concepts of accountability and responsibility. The discussion is therefore limited to aspects of what I see is relevant to the educational role of practitioners as practice educators. Responsibility is linked inextricably with accountability. The focus of responsibility is on the task and not on accounting for it (Cornock 2011). We talk of a ‘responsible person’ as one who accepts and executes an undertaking so long as it is within her/his capabilities (Champion 1991). To be responsible implies being answerable to either another or oneself for some act – it implies a moral accountability for one’s actions as one is capable of rational conduct and fulfilling obligations for vested trust (Brykczynska 1995). Brykczynska goes on to point out that a responsible person is reliable and can justify a trust. Bergman (1981) believes that responsibility is the key component of accountability. However, it is only a part of accountability, as accountability is more inclusive than responsibility. Cornock (2011) suggests that accountability is a higher-level activity than responsibility because the person is not only responsible for an action undertaken but is also required to give an account, reason or explanation for the action. The necessity for this account is not only in instances when something has gone wrong. For instance, it may be required as part of a monitoring system or because things are going right. As an example, in the case of nurses and midwives who assess the clinical practice of pre-registration nursing and midwifery students in the UK, the NMC states that they are accountable for confirming that students have met, or not met, the NMC competencies in practice (NMC 2008a). Before one can be accountable, several preconditions have to be present. These preconditions (Figure. 2.1) are shown in the model used by Bergman (1981:55). The basic precondition is to have the ability (knowledge, skills, values) to decide and act on a specific issue to be able to act autonomously. Next, one must be given, or take, the responsibility to carry out that action. One also needs the autonomy to carry out the action as there is a link between accountability and autonomy (Cornock 2011). Without the autonomy to make decisions freely about the form of action required to be taken, the practitioner is unable to be accountable. If a health professional is instructed to undertake an action, and also the manner in which it should be undertaken, then the health professional is not accountable but responsible. Champion (1991) describes two forms of autonomy: personal and structural autonomy. Personal autonomy refers to the expertise, knowledge and skills related to the defined area of work, the understanding of personal limits of competence and the willingness to take responsibility. Structural autonomy is the ‘authority to act’ given by the organization. To be accountable, one needs the authority to be able to decide whether to act and how to act. A practitioner cannot be accountable if told how to carry out an action and is not able to make the decision on the way the action is to be performed or even whether the action should be carried out at all. When these preconditions are present, one can then be held accountable for the actions one takes. It can thus be expected that ‘an accountable person does not undertake an action merely because someone in authority says to do so. Instead, the accountable person examines a situation, explores the various options available, demonstrates a knowledgeable understanding of the possible consequences of options and makes a decision for action which can be justified from a knowledge base’ (Marks-Maran 1993, in Cornock 2011). Figure 2.1 Model of the preconditions leading to accountability. (From Bergman, R., 1981. Accountability – definition and dimensions. Int Nurs Rev, 28 (2): 53-59. Reproduced with permission from Blackwell Science Publishers.) Professional accountability involves accepting responsibility for professional decisions. Stated more simply, practitioners are ‘entrusted with, answerable for, take the credit and blame for and can be judged within legal and moral boundaries’ (Castledine 1991). The RCN (1990:4) suggests the following working definition of professional accountability for nurses: In view of the substantial clinical role of practitioners, the Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for registrants (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008b) appropriately focuses on professional accountability to patients and clients. Generally, practitioners are in little doubt about their professional accountability towards their patients and clients. Professional accountability for nursing and midwifery education has not received the same attention and interest (Marks-Maran 1995, Harding & Greig 1994). It was not until the publication of the NMC Standards to support learning and assessment in practice (NMC 2008a, 2006) that accountability for student learning and assessment in clinical practice started to receive due attention. There can be few health care practitioners who are not in some way involved in the training and supervision of others. These roles are frequently part of the contract of employment. NMC registrants who support pre-registration nursing or midwifery students and make summative assessment decisions are termed mentors. The educational role of nurses and midwives in clinical practice is formalized by the NMC in the Standards to support learning and assessment in practice (NMC 2008a). These standards specify the responsibility and accountability of NMC registrants who are mentors to pre-registration nursing and midwifery students. Mentors are required to support and make summative assessment decisions of students’ fitness to practise, i.e. determine that students have met the relevant standards of proficiency for entry to the register or for a qualification that is recordable on the register. Those registrants on the NMC register who make summative assessment decisions that determine whether students have met the relevant standards of proficiency for entry to the register must be on the same part or sub-part of the register as that which the student is intending to enter (NMC 2008a). Also, they must hold professional qualifications equal to, or at a higher level than, the students they are supporting and assessing. Additionally, the designation of sign-off mentor has been introduced to sign-off proficiency for all nursing students at the end of the programme. All midwifery mentors are sign-off mentors (NMC 2010a, circular 05/2010). In addition to the possession of the other criteria of a sign-off mentor, a sign-off mentor must have clinical currency and capability in their field of practice and an in-depth understanding of their accountability to the NMC for the decision to pass or fail a student (NMC 2008a, section 2.1.3). In the case of registrants on the HCPC register, practice placement educators will normally be registered with the HCPC in the relevant profession. However, the HCPC recognizes that there are other appropriate practice placement educators whose backgrounds do not match the specific profession that the student is studying. For example, occupational therapists may supervise physiotherapy students in areas such as hand therapy, and nurses may supervise radiographers in aseptic techniques (HCPC 2009a:48). Whilst the Standards of education and training of the HCPC (HCPC 2009a) state that practice placement educators involved in formative and summative assessment must undertake appropriate practice placement educator training, the HCPC does not specify any precise standards to guide the practice of HCPC registrants who assess students’ clinical practice. The requirements for training, supervision and support of pre-registration health care students, and the concomitant assessment of learning, mean that more and more practitioners must take on these roles. Dimond (1994:272) says that ‘for the most part this is unlikely to give rise to many legal issues’. However, an awareness of the potential pitfalls and problems associated with these roles may prevent grief from arising. The rest of the chapter therefore examines accountability issues surrounding the assessment of clinical practice; there is an exploration of the moral and legal obligations that practice educators have to fulfil. The rights of learners and why they have legal means of redress will be explained. Before going on to explore this section, consider the questions posed in Activity 2.2. In its document Making a Difference (Department of Health 1999:24), the government made it clear that it wants practitioners who are fit for purpose, with excellent skills and the knowledge and ability to provide the best care possible in a modern National Health Service (NHS). The point was made that every practitioner shares responsibility to support and teach the next generation of health care professionals. Both the NMC (2008b) and the HCPC (2009a) expect that students who complete pre-registration programmes must have met the standards of proficiency. Prior to entry to the NMC and HCPC professional registers, students must also meet the standards of conduct, performance and ethics, and the health and character requirements of registration (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2010b). To enable the fulfilment of these professional requirements, practice educators need to be cognizant of their responsibility and accountability for the supervision and assessment of clinical practice. For nurses and midwives, direct reference is made to professional accountability for the support and supervision of learners, and, by inference, the assessment of standards of practice, in the NMC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2008b). The Standards state: For nurses and midwives and registrants on the HCPC register, your respective Standards of conduct, performance and ethics (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008b) make it clear that no one else can answer for you and it will be no defence to say that you were acting on someone else’s orders. The NMC states: Both sets of Standards also make it clear that, if you delegate work to someone, your responsibility and accountability is to make sure that the person who does the work is able to carry out your instructions safely and effectively and that proper supervision and support are provided. The NMC further state that nurses and midwives must also confirm that the outcome of any delegated tasks meets required standards. • standards of personal professional practice • standards of care delivery by learners • what is taught, learned and assessed • standards of teaching and assessing It is discussed in Chapter 1 that one purpose of assessment in pre-registration health care education is as a form of quality control for the outcome of the educational process. The educational and professional outcome is a nurse or midwife or physiotherapist or social worker, and so on, who is able to apply knowledge, understanding and skills to perform to the standards required in employment. This professional must have met the standards of proficiency, and prior to entry to the NMC and HCPC professional registers; students must also meet the standards of conduct, performance and ethics, and the health and character requirements of registration. The full realization of this outcome is dependent on the successful achievement of both theoretical and clinical learning and professional development measured by assessment. Assessment is an integral part of professional health care programmes. The processes of clinical teaching, learning and assessment are complex. The committed input of practice educators is required to plan and implement these processes if learning outcomes are to be achieved successfully. I would suggest that this commitment starts with the individual practitioner’s competence and standard of practice. Eraut et al (1995) state that, if aspects of clinicians’ practice are ill-defined, lack quality or make insufficient use of scientific knowledge, the next generation of practitioners will suffer. Much of the learning that takes place in professional education does so in the practice setting (Baskett & Marsick 1992, Schön 1983). Role modelling is an important (Fowler 2008, Pollard 2008, Spouse 1998, Wood 1987), and an almost inevitable, learning strategy in this environment. Within social learning theory, Bandura (1977) suggests that, in role modelling, one person sets a pattern of behaviour that is then copied by another. Learning takes place constantly from observing role models deliver care – these practices are subsequently emulated (Charters 2000). Davies’ (1993) study of role modelling showed that major aspects of nursing were learnt by students when they observed role models providing direct patient care. Students who worked alongside knowledgeable and respected practitioners developed an enthusiasm and commitment to their professional development that was unparalleled by any other learning experience (Spouse 1998). As stated succinctly by McAllister et al (2007:305), ‘students are a product of their schooling’. It is therefore important for the practice educator to adhere to high standards of professional practice so that students learn this high standard of care and are assessed against these professional practices. A high standard of care from students cannot be expected if this is not role modelled. Without modelling high standards of practice one aspect of professional and moral accountability will not be fulfilled. Nicklin & Kenworthy (1995:72) say that ‘assessment inevitably takes place in a role-relationship’. The usual relationship that exists between a student and a practice educator is hierarchical in nature. Neary (2000) pointed out that many practice educators take for granted their position of power in the assessment relationship. Her study in 1996 (in Neary 2000) showed the extent to which this ‘taken-for-granted’ power imbalance became explicit at early stages of the relationship when practice educators quickly confirmed their expertise and established the subordination of their students. In a review of the literature on how practice educators influence practice, Armstrong (2010) found that a student’s actual experience is one of control and coercion. Students felt powerless in challenging practice owing to their lack of status and the fear of jeopardizing their clinical assessment and securing a job. Within this hierarchical situation, one assumption made of the practitioner as practice educator is that she/he possesses the requisite professional qualities and can recognize these in the learner (Harding & Greig 1994). This assumption is of course open to debate. Hepworth (1991:46) expressed her disagreement when she said that: Our assessments, then, are likely to be based on our own standards of practice and perceptions of the situation. Therefore, as practitioners who are also practice educators, there is the responsibility for maintaining competent practice so that assessments are made against these standards. Furthermore, in exercising professional accountability, the NMC (2008b) and the HCPC (2008) require their practitioners on the professional registers to maintain and improve professional knowledge and competence. One point arising from debates on competence is the requirement for the practitioner to keep up to date in order to claim that practice is competent (Hager & Gonczi 1996, McGaghie 1991). Notwithstanding professional requirements, the bottom line in the argument for keeping up to date must be the legal requirement that professional health care practitioners can exercise contemporary professional practices as the law expects current practice to be the accepted practice (Dimond 2011, Young 2009, 1994). There is an expectation that practitioners will employ evidence-based practice and, generally speaking, judges will take a dim view of practitioners who fail to follow the latest clinical guidelines (Young 2009). The duty of care to patients requires practitioners to keep their knowledge and practice up to date (Griffith & Tengnah 2010). Young (1994) states that the legal implication of omitting certain information, or of giving wrong information, is potential negligence on the part of the instructor. This potential exists whenever a failure in instruction jeopardizes the safety of the learner being instructed, or of the patient in her care. I would also suggest that, unless a practice educator is also a competent practitioner, training requirements may not be fulfilled owing to the inability to teach what constitutes competent practice. The practice educator thus has a legal duty, as well as moral and professional accountability to fulfil, in terms of keeping up to date and maintaining competent practice. If it could be established that a patient/client suffered harm as a consequence of negligent instruction (e.g. incorrect information to a student), the patient/client could instigate legal action against the instructor. The practice educator has a dual responsibility: to the patient/client and to the student. A major aspect of the concept of professional negligence in clinical practice is that practice educators have a ‘specific duty or responsibility to foresee or anticipate the possible adverse outcomes of their actions’ (Gunby 2008:414). This applies to both client care and supervision of students. Practice educators must meet a standard of care with respect to the patient/client and a standard of conduct with respect to the student. Practice educators must ensure that students have the necessary clinical experiences and supervision to develop professional competencies in such a way that the patient/client is not harmed in any way while the student is giving the care. The NMC (2008b) and the HCPC (2008) state that patient safety must always take precedence above all else. The NMC and HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008b) make sure that practitioners put the interests of patients, clients and the public before their own interests and those of professional colleagues: i.e. accountability to the patient is always more important than to the student. The Bolam Test (see later discussion) applies to delegation (Dimond 2011). In the eyes of the law, the student’s performance must be equal to that of a registered practitioner. The law is quite clear that a lack of experience or knowledge is never an excuse for incompetent care (Griffith & Tengnah 2010, Young 1994). Students of health care are thus required to provide care equivalent to that of the registered practitioner. One judge (in Young 1994:56) adopted the following view: Therefore, in a highly specialized clinical setting, the standard must be ‘not just that of the averagely competent and well-informed [nurse] but of such a person who fills a post in a unit offering a highly specialized service’ (Wilsher v Essex AHA 1988, in Young 1994). For students to deliver care to a standard equivalent to that of a registered practitioner, that care to be given must be within the student’s capabilities. So far as the NMC and HCPC (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008a) are concerned, it is the registered practitioner working with the student who is professionally responsible for the consequences of the actions and omissions of that student. A pre-registration student, or any other unqualified staff, who is not on the professional register cannot be called to account for her/his actions or omissions as registered practitioners are accountable for care given whether directly or through delegation. It is the personal and professional responsibility of the practitioner who delegates an activity to make sure that the person carrying out the activity is trained, competent and has the necessary experience to undertake the activity safely (Dimond 2011). The delegating professional must also make sure that the appropriate level of supervision is provided. The provision of appropriate levels of supervision is developed in Chapter 7. A number of cases of qualified staff were reported to the then United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC 1996) for inappropriate delegation of responsibilities. One case, which was closed by the Preliminary Proceedings Committee (PPC) of the UKCC, concerned the delegation, by a nurse to a care assistant, of the task of administering an insulin injection. The case was reported on the basis that such administration by a care assistant was prima facie wrong. The issue considered by the PPC was not that the care assistant could not give the injection, but whether the person to whom the responsibility was being delegated was competent to carry out the task. The UKCC concluded that the issue was about supervision, the appropriateness of the delegation and the instruction of unqualified staff, and not about the rigid demarcation of work into tasks to be done by one group or another. It is therefore important to know when and to whom it is safe to delegate. In order to delegate safely and to avoid negligent delegation, the practitioner must be satisfied that the person performing the delegated task is competent to carry it out (Dimond 2011, Young 1994). Making the following two checks may help you to decide when it is safe to delegate. Assess: • The extent of the person’s knowledge and understanding of the task – this requires skilful questioning of the person. This point is developed in Chapter 4. • How skilful the person is in the task delegated – this may require observation and close supervision of the person initially. It is important to provide ongoing supervision. The amount and extent of the supervision will vary from person to person. However, Wood (1987) holds that students must be under strict supervision at all times. This point on supervision of students will be developed in Chapter 6 when management of the continuous assessment process is discussed. The NMC (2008c) has issued detailed guidance on delegation that is available on its website. The guidance considers the principles of delegation by nurses and midwives, the responsibility and accountability of the practitioner who delegates and the documentation required. The practice educator has the responsibility for ensuring that the learning environment is conducive to learning. A wide range of high-quality learning opportunities should be arranged and provided to enable the student to achieve learning outcomes and competencies. The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (NMC 2001) and the Health Professions Order 2001 require the NMC and HCPC to determine the standard, kind and content of training to be undertaken with a view to registration. The standards of proficiency and standards of education required for all pre-registration health care education regulated by the NMC and the HCPC are set out in the Registration Rules (NMC 2004) and Standards of Education and Training under Article 15(1)-(9) of the Health Professions Order, 2001, respectively. Pre-registration nursing and midwifery programmes in the UK now require students to achieve national NMC standards of proficiency (NMC 2010c, 2009). In the case of professions regulated by the HCPC, each profession has defined its own standards of proficiency with varied dates of implementation (HCPC 2011a). It is a requirement that pre-registration programmes must be designed to enable students to apply knowledge, understanding and skills when performing to the standards required in employment and to provide the care that patients/clients require, safely and competently, in order to assume, on registration, the responsibilities and accountability necessary for public protection. Both the NMC and HCPC make it clear that these standards of proficiency are achieved under the direction of the practice educator. In accepting the roles of practice educator as defined by the NMC and the HCPC (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008a), the practitioner is responsible for ensuring that teaching and learning activities, including clinical experiences, assist the student in achieving these standards of proficiency. This requires practitioners to have a sound knowledge and understanding of the learning outcomes to be achieved, expectations of professional conduct and assessment procedures including the implications of, and any action to be taken in the case of, failure to progress. This will enable the practice educator to identify and plan appropriate teaching and learning activities and clinical experiences. The student is entitled to the best instruction available (Young 1994, Wood 1987). Failure to instruct properly could be construed as a negligent act (Dimond 2011, Goclowski 1985). The standard of teaching and learning that an academic institution is expected to provide is generally stated in the educational institution’s ‘student charter’. Service providers for patient/client care enter into contracts with higher education institutions to provide clinical experience for students. Within such contracts is an agreement to provide a standard of teaching and learning in the clinical setting commensurate with that set by the educational institution. To achieve the required standards of the teaching and assessment of clinical practice, practice educators need to attain and maintain competent practice in these roles (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008a). It is recognized that clinical staff exercise a major influence on the quality of pre-registration programmes (Allan et al 2011, Eraut et al 1995). They do much of the teaching, supervision and assessment of students, and as it is likely that this will continue, it is imperative that they are capable of fulfilling these roles. Activities that practice educators are expected to provide will include planning learning opportunities for and with students to enable them to achieve their individual learning needs; facilitating and supporting the learning process; assessing learning; and providing feedback to students on their performance (NMC 2008a, Neary 2000, Eraut et al 1995). To support these educational processes in the clinical setting, higher education institutions include a policy for the management of the assessment of clinical practice in its curriculum document. Generally, the practice educator is required to carry out an initial interview with the student to negotiate and formulate a learning contract/plan to facilitate the achievement of learning outcomes and standards of proficiency. Subsequently, an intermediate interview should take place half way through the placement to review the student’s progress and achievement, and formal feedback given and documented. A final interview allows the practice educator to make a summative assessment of whether the student has achieved the learning outcomes of the placement. Practice educators must be aware of, and be careful that, any policy regulating the assessment of practice is followed, as any deviation from such regulations could give rise to students appealing against any unfavourable assessment decision on the grounds of not having received the supervision, guidance and support to which they are entitled. Cases of students suing nursing institutions in the courts using the above grounds as educational malpractice are well documented in the North American literature (see, for example, Johnson & Halstead 2005, Goudreau & Chasens 2002, Graveley & Stanley 1993, Goclowski 1985, Spink 1983). Courts have recognized that, by virtue of their training, practice educators are uniquely qualified to observe and judge all aspects of their students’ performance. Court decision ruling in favour of the student has been on the basis of practice educators not following established guidelines for the supervision of the student. Practice educators require adequate preparation to enable them to manage the educational activities to support learning and assessment. Subsequently, regular updates are important to keep abreast of developments and/or changes in the curriculum, the assessment process and new local and national policies influencing health care education. In the case of nurses and midwives and registrants with the HCPC, the NMC and HCPC require practice educators to update regularly (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008a). The practices of mentoring and assessing can be enhanced if these ‘update’ sessions are also used as opportunities to discuss assessment problems and how these had been dealt with by individuals. Unfortunately, there is current unease about the expertise of practice educators. Research shows that the initial preparation and continuing development of practice educators are inadequate, particularly with respect to knowledge of programmes and assessment of practice (Luhanga et al 2008, Duffy 2004). Whereas practice educators are personally accountable for their practice of the supervision and assessment of students (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008b), service providers and higher education institutions have the joint responsibility for ensuring that training, support and updating opportunities are provided for practitioners to develop their role as practice educator (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008a, Department of Health 1999). By virtue of their role, practice educators have the right to make, and are indeed vested with the onerous responsibility and accountability for making, professional judgements about the performance of students (HCPC 2009a, NMC 2008a, 2005). These professional judgements require the practice educator to make and report on two important professional decisions: first, they are reporting on the degree to which a student has met the programme learning outcomes and standard; secondly, they are reporting on the ability of the student to provide professionally competent and safe care to the public. Practice educators to students on NMC-approved programmes leading to registration, or a qualification that is recordable on the register, are accountable to the NMC for their assessment decisions about fitness to practise of students to enter the register, and whether they have the necessary knowledge, skills and competence to take on the role of registered nurse, midwife or specialist community public health nurse (NMC 2008a, 2005). Whilst the HCPC does not make a direct reference to accountability for summative assessment decisions, it may be inferred from the Standards of conduct, performance and ethics (HCPC 2008) that HCPC registrants who are practice educators are also accountable, thus: It is important for the practice educator to remember that professional judgements not only assess the student’s current competence but also provide a prediction of the student’s potential ability to practise as a professional nurse or midwife, or physiotherapist, or social worker and so on. Therefore, the conclusion about a student’s performance should attempt to elicit reliability and predictive validity. These important criteria of sound assessments are discussed in Chapter 5. Literature on the assessment of clinical practice abounds with discussions about the subjective nature of this process. Ashworth & Morrison (1991:260) stated that: … assessing involves the perception of evidence about performance by an assessor, and the arrival at a decision concerning the level of performance of the person being assessed. Here there is enormous, unavoidable scope for subjectivity especially when the competencies being assessed are relatively intangible ones. As noted earlier, students have the right to expect that they will be notified of any deficiencies in their performance. The practice educator is behaving unfairly and unethically if the student is not informed about unsatisfactory performance (Orchard 1994). Furthermore, practice educators who fail to evaluate a student’s unsatisfactory performance accurately, either through reluctance to expose the student to the experience of failure or through a fear of potential redress by the student, are guilty of misleading the student, potentially jeopardizing patient/client care and placing the higher education institution in a difficult situation. It is much fairer to students to inform them of unsatisfactory performance as soon as such performance is identified. Informing students of deficiencies in a caring and constructive way allows students the opportunity to improve their performance; not to inform them denies them this opportunity and right (Killam et al 2010, Johnson & Halstead 2005). Practice educators have a moral responsibility to fail incompetent students (Gopee 2008, Beaumont 2004, Ilott & Murphy 1999). Beaumont’s call came after Duffy (2004) reported that practice educators were ‘failing to fail’ nursing students. Being ‘kind’ to students by not failing them is not in the best interest of the student, especially when there is a delay to fail until late into the programme, such as in the final year. Having to inform family and friends that one will now not be able to graduate owing to failure, after having been on the programme for two years, can do untold damage to the self-esteem of that student. Failing to fail students is also not in the best interest of the profession for obvious reasons. An awareness of those factors that contribute to ‘failure to fail’ may be a first step to understanding why difficulties are experienced when dealing with a failing student, and may assist the practice educator in not passing a student when a fail is clearly warranted. It is suggested here that the responsibility for seeking assistance and/or support to make valid summative assessment decisions rests with the individual practice educator. The issues of the unsafe student and ‘failure to fail’ will be explored further in Chapter 7.

Responsibility and accountability surrounding clinical assessment

Introduction

Accountability and professionalism

Accountability and responsibility

Accountability for the assessment of clinical practice

Responsibility and accountability FOR WHAT?

Personal professional standards of practice

Standards of care delivery by learners

What is taught, learned and assessed

Standards of teaching and assessing

Professional judgements about student performance

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Responsibility and accountability surrounding clinical assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access