Describe the process of developing and refining a research problem

Distinguish the functions and forms of statements of purpose and research questions for quantitative and qualitative studies

Distinguish the functions and forms of statements of purpose and research questions for quantitative and qualitative studies

Describe the function and characteristics of research hypotheses

Describe the function and characteristics of research hypotheses

Critique statements of purpose, research questions, and hypotheses in research reports with respect to their placement, clarity, wording, and significance

Critique statements of purpose, research questions, and hypotheses in research reports with respect to their placement, clarity, wording, and significance

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Directional hypothesis

Directional hypothesis

Hypothesis

Hypothesis

Nondirectional hypothesis

Nondirectional hypothesis

Null hypothesis

Null hypothesis

Problem statement

Problem statement

Research hypothesis

Research hypothesis

Research problem

Research problem

Research question

Research question

Statement of purpose

Statement of purpose

OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH PROBLEMS

Studies begin in much the same fashion as an evidence-based practice (EBP) effort—as problems that need to be solved or questions that need to be answered. This chapter discusses research problems and research questions. We begin by clarifying some terms.

Basic Terminology

Researchers begin with a topic on which to focus. Examples of research topics are claustrophobia during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests and pain management for sickle cell disease. Within broad topic areas are many possible research problems. In this section, we illustrate various terms using the topic side effects of chemotherapy.

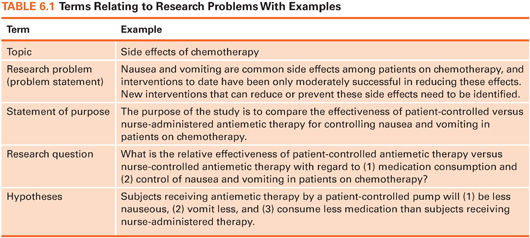

A research problem is an enigmatic or troubling condition. The purpose of research is to “solve” the problem—or to contribute to its solution—by gathering relevant data. A problem statement articulates the problem and an argument that explains the need for a study. Table 6.1 presents a simplified problem statement related to the topic of side effects of chemotherapy.

Many reports provide a statement of purpose (or purpose statement), which is a summary of an overall goal. Sometimes the words aim or objective are used in lieu of purpose. Research questions are the specific queries researchers want to answer. Researchers who make specific predictions about answers to research questions pose hypotheses that are then tested.

These terms are not always consistently defined in research textbooks. Table 6.1 illustrates the interrelationships among terms as we define them.

Research Problems and Paradigms

Some research problems are better suited to qualitative versus quantitative inquiry. Quantitative studies usually involve concepts that are well developed and for which methods of measurement have been (or can be) developed. For example, a quantitative study might be undertaken to assess whether people with chronic illness are more depressed than people without a chronic illness. There are relatively good measures of depression that would yield quantitative data about the level of depression in those with and without a chronic illness.

Qualitative studies are undertaken because a researcher wants to develop a rich, context-bound understanding of a poorly understood phenomenon. Qualitative methods would not be well suited to comparing levels of depression among those with and without chronic illness, but they would be ideal for exploring the meaning of depression among chronically ill people. In evaluating a research report, one consideration is whether the research problem is suitable for the chosen paradigm.

Sources of Research Problems

Where do ideas for research problems come from? At the most basic level, research topics originate with researchers’ interests. Because research is a time-consuming enterprise, curiosity about and interest in a topic are essential to a project’s success.

Research reports rarely indicate the source of researchers’ inspiration for a study, but a variety of explicit sources can fuel their curiosity, such as nurses’ clinical experience and readings in the nursing literature. Also, topics are sometimes suggested by global social or political issues of relevance to the health care community (e.g., health disparities). Theories from nursing and other disciplines sometimes suggest a research problem. Additionally, researchers who have developed a program of research may get inspiration for “next steps” from their own findings or from a discussion of those findings with others.

Example of a problem source for a quantitative study

Beck, one of this book’s authors, has developed a strong research program on postpartum depression (PPD). Beck was approached by Dr. Carol Lammi-Keefe, a professor in nutritional sciences and her PhD student, Michelle Judge, who had been researching the effect of DHA (docosahexaemoic acid, a fat found in cold-water fish) on fetal brain development. The literature suggested that DHA might play a role in reducing the severity of PPD, and so these researchers collaborated in a project to test the effectiveness of dietary supplements of DHA during pregnancy on the incidence and severity of PPD. The researchers found that women in the DHA experimental group had fewer symptoms of PPD compared to women who did not receive the DHA intervention (Judge et al., 2014).

Development and Refinement of Research Problems

Developing a research problem is a creative process. Researchers often begin with interests in a broad topic area and then develop a more specific researchable problem. For example, suppose a hospital nurse begins to wonder why some patients complain about having to wait for pain medication when certain nurses are assigned to them. The general topic is differences in patients’ complaints about pain medications. The nurse might ask, What accounts for this discrepancy? This broad question may lead to other questions, such as How do the nurses differ? or What characteristics do patients with complaints share? The nurse may then observe that the ethnic background of the patients and nurses could be relevant. This may direct the nurse to look at the literature on nursing behaviors and ethnicity, or it may lead to a discussion with peers. These efforts may result in several research questions, such as the following:

What is the nature of patient complaints among patients of different ethnic backgrounds?

What is the nature of patient complaints among patients of different ethnic backgrounds?

Is the ethnic background of nurses related to the frequency with which they dispense pain medication?

Is the ethnic background of nurses related to the frequency with which they dispense pain medication?

Does the number of patient complaints increase when patients are of dissimilar ethnic backgrounds as opposed to when they are of the same ethnic background as nurses?

Does the number of patient complaints increase when patients are of dissimilar ethnic backgrounds as opposed to when they are of the same ethnic background as nurses?

These questions stem from the same problem, yet each would be studied differently; for example, some suggest a qualitative approach, and others suggest a quantitative one. Both ethnicity and nurses’ dispensing behaviors are variables that can be measured reliably. A qualitative researcher would be more interested in understanding the essence of patients’ complaints, patients’ experience of frustration, or the process by which the problem got resolved. These aspects of the problem would be difficult to measure. Researchers choose a problem to study based on its inherent interest to them and on its fit with a paradigm of preference.

COMMUNICATING RESEARCH PROBLEMS AND QUESTIONS

Every study needs a problem statement that articulates what is problematic and what must be solved. Most research reports also present either a statement of purpose, research questions, or hypotheses, and often, combinations of these three elements are included.

Many students do not really understand problem statements and may have trouble identifying them in a research article. A problem statement is presented early and often begins with the first sentence after the abstract. Research questions, purpose statements, or hypotheses appear later in the introduction.

Problem Statements

A good problem statement is a declaration of what it is that is problematic, what it is that “needs fixing,” or what it is that is poorly understood. Problem statements, especially for quantitative studies, often have most of the following six components:

1. Problem identification: What is wrong with the current situation?

2. Background: What is the nature of the problem, or the context of the situation, that readers need to understand?

3. Scope of the problem: How big a problem is it, and how many people are affected?

4. Consequences of the problem: What is the cost of not fixing the problem?

5. Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking?

6. Proposed solution: How will the new study contribute to the solution of the problem?

Let us suppose that our topic was humor as a complementary therapy for reducing stress in hospitalized patients with cancer. One research question (discussed later in this section) might be “What is the effect of nurses’ use of humor on stress and natural killer cell activity in hospitalized cancer patients?” Box 6.1 presents a rough draft of a problem statement for such a study. This problem statement is a reasonable draft, but it could be improved.

Box 6.1 Draft Problem Statement on Humor and Stress |

A diagnosis of cancer is associated with high levels of stress. Sizeable numbers of patients who receive a cancer diagnosis describe feelings of uncertainty, fear, anger, and loss of control. Interpersonal relationships, psychological functioning, and role performance have all been found to suffer following cancer diagnosis and treatment. A variety of alternative/complementary therapies have been developed in an effort to decrease the harmful effects of cancer-related stress on psychological and physiological functioning, and resources devoted to these therapies (money and staff) have increased in recent years. However, many of these therapies have not been carefully evaluated to assess their efficacy, safety, or cost-effectiveness. For example, the use of humor has been recommended as a therapeutic device to improve quality of life, decrease stress, and perhaps improve immune functioning, but the evidence to justify its advocacy is scant. |

Box 6.2 illustrates how the problem statement could be made stronger by adding information about scope (component 3), long-term consequences (component 4), and possible solutions (component 6). This second draft builds a more compelling argument for new research: Millions of people are affected by cancer, and the disease has adverse consequences not only for patients and their families but also for society. The revised problem statement also suggests a basis for the new study by describing a possible solution on which the new study might build.

Box 6.2 Some Possible Improvements to Problem Statement on Humor and Stress |

Each year, more than 1 million people are diagnosed with cancer, which remains one of the top causes of death among both men and women (reference citations).* Numerous studies have documented that a diagnosis of cancer is associated with high levels of stress. Sizeable numbers of patients who receive a cancer diagnosis describe feelings of uncertainty, fear, anger, and loss of control (citations). Interpersonal relationships, psychological functioning, and role performance have all been found to suffer following cancer diagnosis and treatment (citations). These stressful outcomes can, in turn, adversely affect health, long-term prognosis, and medical costs among cancer survivors (citations). A variety of alternative/complementary therapies have been developed in an effort to decrease the harmful effects of cancer-related stress on psychological and physiological functioning, and resources devoted to these therapies (money and staff) have increased in recent years (citations). However, many of these therapies have not been carefully evaluated to assess their efficacy, safety, or cost-effectiveness. For example, the use of humor has been recommended as a therapeutic device to improve quality of life, decrease stress, and perhaps improve immune functioning (citations), but the evidence to justify its advocacy is scant. Preliminary findings from a recent small-scale endocrinology study with a healthy sample exposed to a humorous intervention (citation), however, holds promise for further inquiry with immuno-compromised populations. |

*Reference citations would be inserted to support the statements.

| HOW-TO-TELL TIP How can you tell a problem statement? Problem statements are rarely explicitly labeled. The first sentence of a research report is often the starting point of a problem statement. The problem statement is usually interwoven with findings from the research literature. Prior findings provide evidence supporting assertions in the problem statement and suggest gaps in knowledge. In many articles, it is difficult to disentangle the problem statement from the literature review, unless there is a subsection specifically labeled “Literature Review” or something similar. |

Problem statements for a qualitative study similarly express the nature of the problem, its context, its scope, and information needed to address it. Qualitative studies embedded in a research tradition often incorporate terms and concepts that foreshadow the tradition in their problem statements. For example, a problem statement for a phenomenological study might note the need to know more about people’s experiences or meanings they attribute to those experiences.

Statements of Purpose

Many researchers articulate their research goals as a statement of purpose. The purpose statement establishes the general direction of the inquiry and captures the study’s substance. It is usually easy to identify a purpose statement because the word purpose is explicitly stated: “The purpose of this study was . . . ”—although sometimes the words aim, goal, or objective are used instead, as in “The aim of this study was . . . .”

In a quantitative study, a statement of purpose identifies the key study variables and their possible interrelationships as well as the population of interest (i.e., all the PICO elements).

Example of a statement of purpose from a quantitative study

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of an education-support intervention delivered in home settings to people with chronic heart failure, in terms of their functional status, self-efficacy, quality of life, and self-care ability (Clark et al., 2015).

This purpose statement identifies the population (P) of interest as patients with heart failure living at home. The key study variables were the patients’ exposure or nonexposure to the special intervention (the independent variable encompassing the I and C components) and the patient’s functional status, self-efficacy, quality of life, and self-care ability (the dependent variables or Os).

In qualitative studies, the statement of purpose indicates the nature of the inquiry; the key concept or phenomenon; and the group, community, or setting under study.

Example of a statement of purpose from a qualitative study

The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of religiosity and spirituality on rural parents’ decision to vaccinate their 9- to 13-year-old children against human papillomavirus (HPV) (Thomas et al., 2015).

This statement indicates that the group under study is rural parents with children aged 9 to 13 years and the central phenomenon is the parent’s decision making about vaccinations within the context of their spirituality and religious beliefs.

Researchers often communicate information about their approach through their choice of verbs. A study whose purpose is to explore or describe some phenomenon is likely to be an investigation of a little-researched topic, often involving a qualitative approach such as phenomenology or ethnography. A statement of purpose for a qualitative study—especially a grounded theory study—may also use verbs such as understand, discover, or generate. Statements of purpose in qualitative studies also may “encode” the tradition of inquiry through certain terms or “buzz words” associated with those traditions, as follows:

Grounded theory: processes; social structures; social interactions

Grounded theory: processes; social structures; social interactions

Phenomenological studies: experience; lived experience; meaning; essence

Phenomenological studies: experience; lived experience; meaning; essence

Ethnographic studies: culture; roles; lifeways; cultural behavior

Ethnographic studies: culture; roles; lifeways; cultural behavior

Quantitative researchers also use verbs to communicate the nature of the inquiry. A statement indicating that the study purpose is to test or evaluate something (e.g., an intervention) suggests an experimental design, for example. A study whose purpose is to examine or explore the relationship between two variables is more likely to involve a nonexperimental design. Sometimes the verb is ambiguous: If a purpose statement states that the researcher’s intent is to compare two things, the comparison could involve alternative treatments (using an experimental design) or two preexisting groups such as smokers and nonsmokers (using a nonexperimental design). In any event, verbs such as test, evaluate, and compare suggest quantifiable variables and designs with scientific controls.

The verbs in a purpose statement should connote objectivity. A statement of purpose indicating that the study goal was to prove, demonstrate, or show something suggests a bias.

Research Questions

Research questions are, in some cases, direct rewordings of statements of purpose, phrased interrogatively rather than declaratively, as in the following example:

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to assess the relationship between the functional dependence level of renal transplant recipients and their rate of recovery.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to assess the relationship between the functional dependence level of renal transplant recipients and their rate of recovery.

Question: Is the functional dependence level (I) of renal transplant recipients (P) related to their rate of recovery (O)?

Question: Is the functional dependence level (I) of renal transplant recipients (P) related to their rate of recovery (O)?

Some research articles omit a statement of purpose and state only research questions, but in many cases researchers use research questions to add greater specificity to a global purpose statement.

Research Questions in Quantitative Studies

In Chapter 2, we discussed clinical foreground questions to guide an EBP inquiry. The EBP question templates in Table 2.1 could yield questions to guide a research project as well, but researchers tend to conceptualize their questions in terms of their variables. Take, for example, the first question in Table 2.1: “In (population), what is the effect of (intervention) on (outcome)?”A researcher would be more likely to think of the question in these terms: “In (population), what is the effect of (independent variable) on (dependent variable)?” Thinking in terms of variables helps to guide researchers’ decisions about how to operationalize them. Thus, in quantitative studies, research questions identify the population (P) under study, the key study variables (I, C, and O components), and relationships among the variables.

Most research questions concern relationships among variables, and thus, many quantitative research questions could be articulated using a general question template: “In (population), what is the relationship between (independent variable or IV) and (dependent variable or DV)?” Examples of variations include the following:

Therapy/treatment/intervention: In (population), what is the effect of (IV: intervention vs. an alternative) on (DV)?

Therapy/treatment/intervention: In (population), what is the effect of (IV: intervention vs. an alternative) on (DV)?

Prognosis: In (population), does (IV: disease or illness vs. its absence) affect or increase the risk of (DV)?

Prognosis: In (population), does (IV: disease or illness vs. its absence) affect or increase the risk of (DV)?

Etiology/harm: In (population), does (IV: exposure vs. nonexposure) cause or increase risk of (DV)?

Etiology/harm: In (population), does (IV: exposure vs. nonexposure) cause or increase risk of (DV)?

Not all research questions are about relationships—some are descriptive. As examples, here are two descriptive questions that could be answered in a quantitative study on nurses’ use of humor:

What is the frequency with which nurses use humor as a complementary therapy with hospitalized cancer patients?

What is the frequency with which nurses use humor as a complementary therapy with hospitalized cancer patients?

What are the characteristics of nurses who use humor as a complementary therapy with hospitalized cancer patients?

What are the characteristics of nurses who use humor as a complementary therapy with hospitalized cancer patients?

Answers to such questions might be useful in developing effective strategies for reducing stress in patients with cancer.

Example of a research question from a quantitative study

Chang and colleagues (2015) undertook a study that addressed the following question: Among community-dwelling elders aged 65 years and older, does regular exercise have an association with depressive symptoms?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree