We therefore need to explore ways of increasing donor numbers in order to offer all suitable patients the chance of a transplant.

Contraindications to Renal Transplantation

Although the majority of patients may request a transplant, transplantation may not be suitable for all those with ERF because of possible medical complications.

Malignancy

Malignant disease must be excluded prior to transplantation as the immunosuppressive regime may cause accelerated growth of the malignancy and may encourage secondary spread. If the patient is known to have had cancer in the past, it is important to ascertain the type of malignancy, the stage of development and the treatment received. Transplantation may still be possible provided that curative treatment has been given and sufficiently long follow-up has occurred to exclude recurrence. Current UK guidelines recommend a potential recipient be disease free for two years prior to listing for transplant (Dudley and Harden 2011). However, certain cancers, such as breast, colorectal and melanoma carry a higher risk of recurrence and a disease free period of five years may be required. The importance of time to transplant following treatment of a malignancy is shown by Penn’s (1997) paper using data from the United States: in 1137 recipients who had been treated for a malignancy prior to transplantation, the recurence rate was:

The risk of recurrence of cancer should be discussed fully with the recipient prior to listing for transplant. Guidance regarding specific malignancy and risk of recurrence can be obtained from the Israel Penn International Transplant Tumor Registry (www.ipittr.org, accessed 20 May 2013).

Recurrent disease

It is important to consider the patient’s primary renal disease as in some cases the disease may recur and destroy the new kidney. Renal disorders with a very high recurrence rate include primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) (causing massive proteinuria and scarring of the glomeruli), mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (an immunological disorder of the glomeruli) and IgA nephropathy. Recurrence of disease is estimated to account for up to 5% of graft loss post transplant (Chadban 2001). Transplantation can still be considered but only after counselling and explanation of the risks to the patient. Many centres would advise against living related donation in this situation, however it may still be possible providing both donor and recipient are fully aware of the risk of recurrence.

Other conditions, such as Goodpasture’s syndrome and the other vasculitic illnesses need to have been fully treated before going ahead with transplantation because of the risk of damage in the new kidney in the presence of active disease. Twelve months is normally considered the earliest that transplantation would be considered following initial presentation of the disease. Several other diseases, such as diabetes, can cause microscopic changes in the kidney after many years, but rarely lead to graft loss.

Hepatitis virus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Patients who are hepatitis B or hepatitis C positive may be at risk of progressive liver disease after transplantation due to the impact of the immunosuppressive therapy. Consultation with a hepatologist maybe required and possibly liver biopsy in order to determine activity of the virus and presence of liver damage. Many patients who are hepatitis B or C positive have no disease or quiescent disease and are therefore suitable for transplantation. Careful monitoring in this group of patients is required after transplant to ensure early detection of increased viral activity and to ensure antiviral therapy is continued. Previously, infection with HIV was considered an absolute contraindication to transplantation, however the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as a means of controlling HIV infection has made transplantation possible in this group of patients, with studies showing no difference in graft or patient survival when compared with non-HIV infected transplant recipients (Martina et al. 2011).

Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease

Many people with diabetes can receive a renal transplant, but they are at risk from other complications of their diabetes. Cardiovascular disease is seen primarily in those with Type 2 diabetes, and may contribute to higher levels of morbidity and death. It is important to assess vessel patency prior to transplantation, as severe atherosclerosis of the iliac vessels may at worst preclude transplantation and at best complicate the transplant surgery.

Evaluation for Transplantation

Age

Morbidity and mortality after kidney transplantation tend to increase with age and therefore the age of the recipient must be classed as a risk factor. Age must also be considered within the context of other risk factors, such as advanced cardiovascular disease and diabetes. There is no age barrier for transplantation, health is assessed on an individual basis, and physiological rather than chronological age and the existence of other risk factors are seen as the important assessment issues. Many units have patients of 70 years and over who have progressed well following a kidney transplant. However, with demand far exceeding supply and studies reporting smaller changes in improvements in quality of life for the older age groups and a significantly increased risk of death within five years of transplantation for those over 60 years of age (Johnson et al. 2010), some may question the use of such a precious and scarce resource in this group (Box 10.1).

- Renal transplants: demand far exceeds supply.

- Younger patients are shown to gain greater life satisfaction after a transplant.

- Older patients are at greater risk of complications.

- Should younger patients be given priority over the older group?

Polycystic kidney disease

This inherited kidney disease can result in several members of a family receiving ERF therapies. The native cystic kidneys may be very large, thus leaving little space for the transplant, and there may also be an increased risk of bleeding and infection. It may be necessary to perform a unilateral, or in severe cases a bilateral nephrectomy prior to listing for transplantation.

Urinary tract

It is important to assess that there are no problems with the bladder and urethra and that there will be no difficulties following transplantation; if it is felt that the bladder capacity is unacceptably low, surgical enlargement may be possible. In the presence of a history of repeated urinary tract infections with bilateral reflux, it may be necessary to undertake a bilateral nephrectomy prior to transplantation to reduce the risk of posttransplant infection.

Cardiac disease

Cardiovascular disease is known to be a major cause of comorbidity in the renal population. Routine investigations such as an electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram and a cardiac history are essential for all patients undergoing assessment for transplantation. Those patients who are in the high-risk groups for cardiovascular disease (e.g. older patients and those with diabetes) maybe reviewed by a cardiologist and undergo further investigation. There is no evidence at the present time that intervention in this high risk group results in better outcomes following transplantation, cardiac screening may be most useful in identifying the high risk patient in order to exclude them from the transplant waiting list (Dudley and Harden 2011).

Peptic ulceration

A history of indigestion and/or peptic ulceration must be noted and endoscopy undertaken if active ulceration is a possibility, as those with active ulceration risk bleeding after transplantation due to the action of the steroid therapy. Treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in combination with antibiotics if required to eradicate Helicobacter pylori should be given prior to transplantation if active disease is present. Many centres also use PPI as prophylaxis in all recipients during the first 3–6 postoperative months.

Respiratory disease

Pulmonary tuberculosis will require treatment before listing for transplantation. Patients with a history of tuberculosis and those who have visited or lived in high-risk areas will require prophylaxis with isoniazid for at least a year following transplantation.

Patients should also be strongly advised to stop smoking and should be offered information regarding smoking cessation strategies and support systems.

Obesity

Obesity may make the transplant surgery difficult and increase the risk of postoperative complications. Nutritional advice should be given before and after transplantation (Chapter 13).

Oral hygiene

Dental hygiene and assessment of dental state are essential. Any gum infection or dental problems should be dealt with prior to transplantation. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) can cause gum hypertrophy, which is made much worse in the presence of poor hygiene.

Pretransplantation Preparation

Patients may be referred for transplantation during different phases of the disease process; some may be in the predialysis stage, others may already be established on dialysis therapy. UK guidelines allow a patient to be listed on the deceased donor list once he/she is within approximately 6 months of requiring dialysis (GFR of <15 ml/min). A pre-emptive transplant gives a better outcome compared to having to spend time on dialysis. Additionally a waiting time of more than 6 months has been linked with an increased risk of graft failure, however this risk does not increase further if waiting time increases beyond 2 years (Johnson et al. 2010). A planned pre-emptive transplant from a living donor gives the best outcome in terms of graft success and recipient health. Early transplantation before the need for dialysis therapy is welcomed from a clinical perspective, but may prove difficult psychologically if emotional adjustments have not been successfully negotiated and the patient and family are still reeling from the impact of the disease. A structured approach to predialysis education and counselling should include discussion of suitability for transplantation, and the likelihood of any potential living donors being found. Suitable patients can then be seen for pretransplant education and assessment, and friends or relatives who are interested in living donation can be contacted at this early stage. An overview of the psychological support required prior to transplantation is outlined in Chapter 4.

Boxes 10.2–10.4 show useful checklists for the pretransplant stage. Pre transplant assessment is usually a multi-disciplinary process, involving medical, surgical and specialist nurse input. A systematic approach to assessing patients for suitability for transplantation should include those approaching ERF as well as those on dialysis. This is of particular importance when a suitable living donor may be found, thus allowing pre-emptive transplantation.

| Orientation | Tour of the transplant unit |

| Waiting list | How it works, how to manage waiting time |

| Planning for the transplant call | Arrange child/pet/others care |

| Transplant call | What to expect, transport arrangements |

| Contact numbers | Holiday arrangements |

| Inpatient care | |

| Pre- and postoperative care | What to expect, discharge arrangements, followup |

| Transplant nurse specialist | Contact card – further contact |

- Dental check: date of last check.

- Female patients, last cervical smear: date of last smear and result.

- Breast self-examination.

- Weight.

- Height.

- Body mass index.

- Surgical, anaesthetic, patient survival rates.

- Graft survival rates–deceased and living donor.

- Lymphoma.

- Cytomegalovirus.

- Cardiovascular.

- Skin cancer.

- On deceased donor transplant waiting list.

- Living donor programme.

- Await further investigations and/or referral.

- Patient undecided – does not want a transplant.

- Unsuitable for transplant due to . . .

Specific Pretransplant Anxieties and Fears

Specific issues concerning body image are discussed in Chapter 4: other anxieties include acceptance of the transplant as part of the ‘self’ and guilt over benefiting from traumatic death. There are also very specific challenges relating to patients’ education and understanding of their immunosuppressive therapy.

It is vital that patients understand the need to continue with their antirejection therapy for as long as they have their transplant. Many patients believe that it will only be necessary to take the drugs until the kidney settles into the body. There are great challenges for the transplant team to ensure that patients are well informed about their medication.

There is evidence that non adherence to prescribed medication in transplant recipients leads to an increased risk of graft loss (Pinsky et al. 2009). A meta-analysis of 147 studies regarding the prevalence of non adherence in solid organ transplant recipients found that immunosuppression non adherence was highest in kidney transplant recipients (Dew et al. 2007). A variety of explanations have been given for these difficulties. These include the effects of immunosuppression on physical appearance, inability to accept the lifestyle limitations, misinformation given by one patient to another, poor education given by staff and fear of long-term side effects. Sometimes, those who have had difficulty in accepting dialysis are exemplary transplant recipients because the post-transplant lifestyle is especially precious.

It is inappropriate to refuse transplantation to patients who are perceived as high risk for nonadherence. It is important to offer extensive pretransplant counselling to explore the reasons for not taking healthcare advice and to ensure additional posttransplant support is available to facilitate adherence to medication therapies. This may necessitate changing to an immunosuppression regime with a different side effect profile. Close monitoring of immunosuppressant levels and ensuring attendance at clinic visits are vital basic steps to detect possible non adherence.

Transplant Waiting List

Once the pretransplant assessment has been completed satisfactorily and the tissue-typing and blood-grouping details are finalised, the name of the patient will be added to the national waiting list. Waiting time is impossible to predict.

It is important to explain to patients that the transplant waiting list is very different from other hospital waiting lists in that they do not simply have to wait until their name reaches the top to receive a graft. The transplant list is essentially a pool of recipients, and each transplant is allocated on the basis of the closest match. Therefore, their name will join the recipient pool and they must wait for the best match for them. This is a difficult concept to understand and some patients become distressed if another patient, who has waited less time, is transplanted before them.

It is also important that patients do not sit by the phone all day waiting for ‘the call’, thus greatly restricting their lifestyle. Patients are encouraged to keep as active and as healthy as possible whilst waiting and to continue as normal a lifestyle as possible. Some patients may still feel ambivalent about a transplant at this time. Specific fears and anxieties may need to be explored and support given within the context that patients must be allowed the time to decide the best treatment for themselves. Ongoing contact with the transplant nurse specialist is vital during the waiting time and it is recommended that those who are waiting are contacted every 12 months and offered support and reassurance. Support is especially important at times of additional stress such as when a fellow dialysis patient receives or rejects a kidney.

Donor and Recipient Matching

Immune system: overview

The human body has a complex system of defences that can provide protection against infection and disease. This system has the ability to target, isolate and destroy potentially harmful invaders. This destruction is achieved in three stages – first by the recognition of structures on the invader (antigens) which are not present in the host. Antibodies and T cells that can recognise the antigens as ‘foreign’ are then produced. These antibodies and T cells then attach to the invader and destroy it both directly and by recruiting other mechanisms of destruction. Exactly the same happens to a transplant unless it is from an identical twin. The ‘foreign’ antigens on the transplant induce antibodies and T cells. These target the transplanted organ and do their very best to destroy it. The term ‘transplant antigens’ is used to describe those antigens that are most important in this regard. Only two are really important: the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system and the ABO system (see below). In order to prevent rejection it is necessary to circumvent the immune system (by matching and cross-matching) and to suppress the immunological response.

Components of the immune system

Leukocytes (white blood cells)

These comprise the cells that produce the antibody (B lymphocytes), recognise the foreign antigens (T lymphocytes), directly destroy invaders (activated T lymphocytes), or can be called in to help with the destruction process (monocytes, polymorphs and eosinophils). Thus, it can be seen that the lymphocytes play several roles and therefore have the major influence on graft acceptance.

Lymphocytes

These comprise 20% of the total white blood cell count and are made up of several groups of cells with specialised functions. The term ‘orchestra’ is often used to describe the mode of operation. Each section of the orchestra is made up of individuals with similar but not identical characteristics. The overall result of the orchestra playing is a result of each section performing in concert with the others.

Lymphocyte types

- T cells: these have antigen recognition structures fixed to their surface.

- B cells: these have antigen recognition structures that can be secreted (antibodies).

T cells and B cells can be naive or activated. T cells can be activated to various functions, namely helper, killer or tolerant status. B cells can be activated to produce antibody or memory.

Each naive lymphocyte has an antigen recognition structure that is unique, for example different from other members of its section and thus capable of seeing a different antigen. In this way literally millions of ‘foreign’ antigens can be recognised. Each time a recognition event occurs, a naive cell becomes activated and divides. Thus, even if a single cell recognises an antigen as foreign it keeps dividing until it forms a significant number of identical cells (a clone), all capable of recognizing the antigen.

Depending on influences from other sections, T cells can help B cells produce antibody (helper T cells), kill targets bearing the antigen directly (killer T cells), or become tolerant (i.e. capable of recognizing the antigen but not producing a damaging response to it). B cells can produce antibody in around 8–10 days if they see it for the first time (naive B cells) or within 24 h if they have seen it before (memory B cells). B cells produce much more antibody if they get help from the T cells, which can themselves see the same antigen.

One point about antibody production that is relevant to transplantation is that the process that produces it is long lived. This is very positive for vaccination programmes, where having antibody around for years and years is very beneficial, although negative of course for transplantation.

ABO blood groups

The ABO system of human blood groups was described by Landsteiner in 1902. (Nobel Prize 2013). Blood group is determined by A and B antigens on the surface of the red blood cells. Each individual has one of the four basic blood group types – O, A, B or AB.

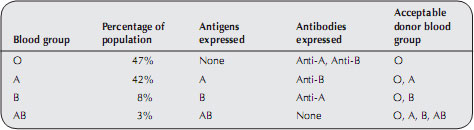

Each individual has antibodies to the blood group antigens that they do not express (Table 10.1). Antibodies against the blood group antigens can cause hyperacute rejection and therefore matching of blood group between donor and recipient is vital. Blood group O organs can be transplanted into all groups; O is classified as the universal donor. Blood group AB recipients can receive organs from all groups; AB is classified as the universal recipient. A small proportion of people with group A belong to a subgroup defined as A2, and have reduced expression of A antigen. These kidneys may be successfully transplanted into O or B, or A2B into AB, recipients with low anti-A titres (Bryan et al. 2007).

Table 10.1 The ABO blood group system.

Recent advances in pretransplant care have allowed transplants to take place between a blood group incompatible (ABOi) donor and recipient. Such programmes are suitable only for living donor transplants due to the pretransplant treatment required for the recipient. Antibodies can be removed from the recipient using various strategies, including plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption. More potent immunosuppressive medications may also be required. This strategy allows transplants to take place between donor and recipient pairs that would previously have been unsuitable, thus increasing the chance of transplantation for many recipients. The risk of rejection of the transplant, failure of the graft and of serious side effects of immunosuppression are higher than with a blood group compatible transplant. It is important that recipients of this type of transplant are fully informed of the risks prior to undertaking this procedure.

Histocompatibility antigens

A further set of proteins that can trigger the B and T cell response are the transplantation antigens or the histocompatibility antigens. The histocompatibility antigens can be divided into two groups – major and minor.

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC)

This system, first discovered in the mouse by Peter Gorer at Guy’s Hospital in the late 1930s, is, as the name suggests, the most important system in transplantation and indeed in immunity to infection. The human system is termed HLA (for human leukocyte antigen) and was first identified in the 1960s. The sera from pregnant women were found to have antibodies that recognised lymphocytes from their partners and from some random blood donors. The reason for this is that pregnancy is in some ways like a transplant. Passage of blood from partner or child to mother results in T cells and antibody being produced to the foreign antigens on the blood cells. Since the most potent foreign antigens are those of the HLA system, most of the mother’s response is directed against them and the long-lived antibody-producing cells remain in her blood. These antibodies can persist for over 40 years.

The HLA system is complex. There are four main series important for transplantation – A, B, C and DR. There are over 30 antigens in each series. Each person can have two from each series (one from each parent). The permutation on 2/30 from A, 2/30 from B, 2/30 from C and 2/30 from DR means that, outside a family, it is very rare for individuals to have identical HLA types. Luckily for matching in renal transplantation, DR is dominant. However, most of the antibody and T-cell response is produced to A, B and C.

The rules for HLA and matching are not nearly so clear-cut as the rules for ABO, but there are several strong guidelines:

- Transplantation of a kidney into someone who has antibodies directed to a foreign (mismatched) HLA antigen on that kidney will result in hyperacute rejection.

- Transplantation of a kidney into someone who has strong memory to a foreign (mismatched) HLA antigen on that kidney will result in very rapid rejection.

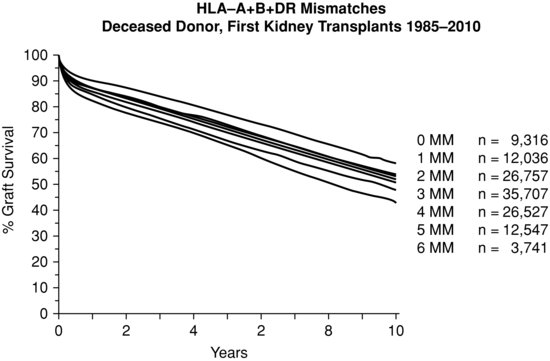

- Transplantation of a kidney with two mismatches at DR will have more rejection than one with no mismatch at DR. However, rejection episodes can be treated or mismatched patients given additional immunosuppression. The total number of mismatches has a bearing on long-term outcome (Figure 10.2).

Newer techniques allow organs to be transplanted where there is HLA incompatibility (HLAi) providing antibodies are removed or lowered to an acceptable level prior to transplantation. There are various techniques used to remove antibodies, for example, plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption, in a similar strategy to that used in ABOi transplantation. This procedure is only suitable for living donation as the antibody removal must be carried out in the period leading up to the transplant operation. The risks of transplant rejection, graft failure and serious infection are twice as high as for antibody compatible transplants so patients contemplating this procedure must be fully aware of the risks before proceeding. Despite the risk this treatment may offer some patients their only chance of receiving a transplant, particularly as they may be unlikely to be offered a deceased donor kidney if highly sensitised, and many are willing to accept the risks involved.

Donor and recipient matching

The majority of organs for transplant come from deceased donors. It is essential to match for blood group and to achieve the best DR match possible. Since antibodies can be induced to pregnancies, transfusions or previous transplants and can be boosted by infection, regular screening of patients on the waiting list is necessary to maintain knowledge of their current antibody status. Donors are avoided if they contain any mismatch to which the recipient has antibodies in current or recent serum.

Pretransplant cross-match

Immediately prior to transplant a cross-match test is performed in the tissue-typing laboratory. A recent blood sample and selected past samples from the recipient are checked against donor lymphocyte cells. If the donor cells react (die), the result is termed a positive cross-match; the recipient is adversely reacting to the donor antigens. In the presence of a positive cross-match, transplantation cannot proceed, as the transplant would be rejected.

Traditionally a cross-match was performed prior to deceased donor transplantation and the results were obtained before the transplant operation could proceed. Recognition of the significance of shorter cold ischaemic times (CIT) in improved short-term graft success rates (Johnson et al. 2010) has led to the introduction of retrospective cross-matching. In this situation the transplant proceeds without waiting for the cross-match result to be available. This can only occur if the recipient has had regular blood samples sent to the laboratory for antibody testing and is known to be nonsensitised. Careful history should be taken at time of transplant to ensure the recipient has not received any recent blood transfusions that would affect antibody status.

Sensitisation

When there is a positive cross-match, the recipient is sensitised to that donor. The higher the level of sensitisation, the greater will be the difficulty in finding a transplant that will not reject.

Sensitisation can occur during pregnancy (to partner’s antigens), during blood transfusion and after transplantation. In order to reduce the risk of sensitisation it is important to minimise the giving of blood transfusions.

Some recipients may have a high level of sensitisation. The patient’s serum is tested periodically against a representative panel of cells from many donors. If the patient does not react with the various donors tested then they are classified as unsensitised. If the blood reacts with 50% of donors (50% of the panel or 50% Panel Reactive Antibody (PRA)) they are 50% sensitised, and if blood reacts with 100% of donors they are highly sensitised. Unfortunately, some highly sensitised candidates wait many years for a compatible transplant, although the antibodies responsible for sensitisation can decrease with time.

United Kingdom matching system

Within the United Kingdom, each transplant centre has a local list of recipients awaiting transplant. There is a national database held at NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) in Bristol. Each deceased donor is tissue-typed at the local transplant centre and the details sent to NHSBT, where the closest tissue match is found from the central computer. The kidneys are then sent to the recipient centre for transplant.

A new scheme for the national allocation of kidneys was adopted in the United Kingdom in 2006. The scheme is based on HLA matching, gives priority to paediatric and highly sensitised patients (i.e. patients with high levels of HLA antibodies) and uses a point score to differentiate between equally matched patients. The aim of this scheme was to reduce the variability in deceased donor waiting times across the United Kingdom.

The scheme has five tiers. Tier 1 kidneys are offered to paediatric patients with no mismatched HLA antigens at HLA-A, -B and -DR (termed a 000 mismatched transplant) who are known to be highly sensitised. If there are no such patients in tier 1, then kidneys are offered in tier 2 to 000 mismatched, nonsensitised paediatric patients. If there are no patients in either tier 1 or 2 then kidneys are offered in tier 3 to 000 mismatched adult patients who are highly sensitised. If no match is found in tier 3 then the offer moves to tier 4 which includes all other 000 mismatched adult patients and favourably matched (i.e. no mismatch at HLA-DR and a maximum of one mismatched antigen at both the HLA-A and HLA-B locus; 100, 010, 110 mismatch grades) paediatric patients. Tier 5 includes all other patients. Paediatric patients in tiers 1 and 2 are prioritised according to waiting time. In the remaining tiers, patients are prioritised according to a points score, including: waiting time, age, donor recipient age difference, geographical location of patient relative to donor (NHSBT 2012).

Review of the scheme has shown that matching is still relevant, however, advances in immunosuppression over the last ten years have meant that only the most poorly matched grafts (two antigen mismatch at HLA-DR locus) are associated with worse outcomes when compared to 000 mismatched grafts (Johnson et al. 2010).

Deceased Donation

The majority of renal transplants currently performed in the United Kingdom are from from deceased donors. Deceased donors fall into two categories, donation after brain death (DBD) or donation after circulatory death (DCD). Donation after brain death donors are patients who have suffered irreversible brain stem damage (brain stem death) and are maintained on a ventilator within a critical care unit.

Causes of brain stem death

The most common causes of brain stem death are listed in Box 10.5.

Cerebral swelling resultant from trauma or anoxia and intracerebral bleeding can cause raised intracranial pressure, which forces the cerebral hemispheres through the tentorial hiatus, thus compressing the brain stem and interrupting its blood supply. Such herniation of the cerebral tissue is usually described as ‘coning’ and results in irreversible damage to the brain stem.

Brain stem functions

The brain stem is responsible for the capacity to breathe spontaneously and the capacity for consciousness. If the brain stem is irreversibly damaged then there is loss of function and it is argued that ‘death entails the irreversible loss of those essential characteristics which are necessary to the existence of a living human person’.

Brain-stem death diagnosed by signs of irreversible damage to the brain stem is an accepted concept in most countries of the world.

Brain-stem death diagnosis

Tests to diagnose brain-stem death originated from the Harvard Medical School criteria (Harvard Medical School 1968) which were published in the United States in 1968. A UK Code of Practice for the diagnosis of brain stem death was agreed by the Conference of Medical Royal Colleges in 1976 and most recently updated in 2008.

- Intracerebral bleed or infarction.

- Head trauma.

- Cerebral hypoxia due to:

- respiratory arrest;

- cardiac arrest.

- respiratory arrest;

- Smoke inhalation/carbon monoxide poisoning.

- Cerebral tumour.

- Drug overdose.

- Intracranial infection.

Certain conditions must be met before brain-stem death testing can take place:

- The patient is deeply comatosed, unresponsive and apnoeic with lungs artificially ventilated.

- There is a positive diagnosis or known condition that has led to the diagnosis of irreversible brain damage.

- Potentially reversible causes of coma have been excluded.

Possible causes of coma that must be excluded are primary hypothermia (the patient’s temperature must be greater than 34 °C for testing to take place), effect of depressant drugs, potentially reversible circulatory, metabolic and endocrine disturbances and potential causes of apnoea. Testing will then take place to ascertain the absence of brain stem reflexes:

- the pupils are fixed and do not respond to sharp changes in light intensity;

- there is no corneal reflex;

- the oculovestibular reflexes are absent;

- no motor responses within the cranial nerve distribution in response to stimulation of any somatic area;

- there is no cough reflex response to bronchial stimulation by a suction catheter placed down the trachea to the carina, or gag response to stimulation of the posterior pharynx with a spatula;

- there is no evidence of spontaneous respiration or respiratory effort during the apnoea test (loss of capacity for spontaneous breathing).

Declaration of brain-stem death

The UK Code of Practice recommends that brain-stem death testing should be carried out by two medical practitioners who have been registered for a minimum of five years and ‘who have expertise in this field’. At least one should be a consultant. Testing should be performed by two doctors together and should be performed completely and successfully on two occasions. Neither of the doctors should be a member of the transplant team or associated with potential transplant recipients.

Time of death

The time of completion of the first set of tests is legally the time of death, and this should be recorded as such on the death certificate.

Contraindications to organ donation

- Known or suspected Creutzfelt–Jacob disease (CJD) and other neurodegenerative diseases associated with infectious agents.

- Known HIV disease (but not HIV infection alone).

The following conditions may preclude donation but individual donors should be discussed with the Specialist Nurse for Organ Donation as they may still be suitable:

- disseminated malignancy;

- melanoma (except local melanoma treated > 5 years before donation);

- treated malignancy within 3 years (except nonmelanoma skin cancer);

- age > 90 years;

- known active tuberculosis;

- untreated bacterial sepsis.

It is recommended that critical care staff consider organ donation in all those with brain stem death and refer to the Specialist Nurse for Organ Donation for a decision regarding medical suitability. The Organ Donation Task Force recommends that consideration for organ donation should be a routine part of end of life care (Department of Health 2011).

Patients from high-risk groups (as defined by the Department of Health 2011) should also be excluded. In order to keep transplants safe, the Department of Health guidelines state that ‘certain medical and social information’ must be given. Therefore, donor families are given an information sheet (Box 10.6) and asked to read these questions and answer ‘to the best of their knowledge’.

Asystolic donation (nonheart beating)

An initiative at the Leicester General Hospital in 1992 showed that asystolic (nonheart-beating) donation could become an increasingly important source of renal organs. Leicester identified asystolic donors in the medical wards and the accident and emergency department of the local hospital. At the time of asystole and following certification of death (providing that there were no medical contraindications to donation), an intra-aortic catheter was inserted and ice-cold perfusion of the kidneys commenced. Such perfusion reduces the warm ischaemic damage and allows time for medical/ nursing colleagues to approach the family and the coroner for permission to proceed to donation. If permission was granted the kidneys had to be removed within 40–45 min of asystole in order to avoid irreversible renal damage.

Ethical concerns about the insertion of the catheter before consent has been given by the family were widely discussed during the planning of this programme and health personnel, the coroner and the general public groups that were consulted gave consent to this initiative. However, following the widely reported problems with organ retention after postmortem without family consent that occurred at Alder Hey and other hospitals, it was decided by the Leicester group that they must obtain consent before insertion of the intra-aortic catheter. This decision undoubtedly affected the length of time between asystole and cold perfusion of the kidneys. However, the Human Tissue Act (2004) made the wishes of the potential donor central to any decision to proceed.

Interestingly, results suggest a marginally higher rate of relative consent in asystolic donation than is usually achieved in brain-stem death donation. This may be due to the skill of the staff requesting and also the fact that with asystole the patient appears ‘dead’ in the conventional sense (cold, pale and cyanosed), thus there may be less psychological denial for the family.

Several other centres have introduced asystolic donation programmes and they are providing a useful additional supply of kidneys. However, the limiting factors will be the need for a rapid response time from the retrieval teams and the need for catheter insertion expertise. Such factors may preclude donation from hospitals that are some distance away from the transplant centre.

Requesting donation

In the United Kingdom, the legal requirements for organ donation are laid down in the Human Tissue Act (2004). This Act established the Human Tissue Authority (HTA) as the regulatory body for all matters concerning the removal, storage, use and disposal of human tissues (except gametes and embryos) for scheduled purposes, and includes responsibilty for living donor transplantation. The HTA’s code of practice on consent sets out guidance on how the law should be applied, encompassing issues of consent.

In practice, it is the next of kin or the patient’s executor who is usually approached to give permission for donation. If the patient has signed a donor card there is no statutory requirement to approach the family, but in practice the views of the family are always sought and if objections are raised donation does not occur.

If the next of kin cannot be notified, the body remains in the possession of the hospital. In such cases the hospital manager can give permission for donation as long as reasonable enquiries have been made and that there is no reason to believe that the deceased had expressed objections.

Religious beliefs

As far as it is known, no major religious groups in the United Kingdom object to the principles of organ donation and transplantation. Some groups feel that it is only permissible if donors themselves had requested donation. These groups include, in particular, Orthodox Jews, Christian Scientists and some Hindu groups. Jehovah’s Witnesses have religious objections to blood transfusions, but feel that donating or receiving organs is a matter for all Jehovah’s Witnesses to decide for themselves.

It is often thought that the Muslim faith does not support donation and anecdotal evidence suggests that British Muslims are, in general, reluctant to donate organs. However, recent legislation has approved donation and transplantation in Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia. Also, a fatwa issued by the Muslim Law Council has stated that Muslims may donate organs. They may carry donor cards and their next of kin may give permission for donating. Previous reluctance to donate may have been cultural rather than religious and therefore information and liaison with Muslims will be vital in order to encourage donation.

Roderick et al. (2009) states that there is a documented fourfold increased prevalence of ERF in the black and south-Asian patient groups. Major causes are the higher incidence of hypertension and diabetes combined with other reasons that are, as yet, unknown. Although none of the major religions forbids organ donation, there are fewer deceased organ donations from this community. The reasons for this are complex but include mistrust of the NHS, lack of available culturally sensitive information and lack of engagement with the community in general (Department of Health 2010). Language and cultural barriers seem to have inhibited the uptake of public health messages pertinent to organ donation and transplantation.

The Organ Donor Task Force (ODTF) was set up in 2006 by the UK government with the aim of increasing donation rates in the United Kingdom. The ODTF recommended the need to engage with black and minority ethnic groups in order to address the shortage of donor organs from this group.

Other issues may also be adversely affecting the deceased donation rate from within all groups, particularly aspects relating to gaining consent from the bereaved.

Fear of increasing the distress of the family

Critical care staff have expressed fears that offering donation may increase the distress of the bereaved; however, experience suggests that offering the choice to donate, if performed with empathy, does not increase distress (Simpkin et al. 2009). Indeed, donor families report that the act of donation brings comfort and something positive in an otherwise negative situation. One American study found that families were more likely to consent to donation when hospital staff mentioned that by donating they would offer help to others (Siminoff et al. 2001). In the presence of a diagnosis of brain stem death there can be no hope for the patient but donation can be an option offering hope of life for others.

Acceptance that death has occurred

It is crucial that the bereaved family have accepted the fact that death has occurred before donation is requested. In the case of brain stem death the acceptance of death is more difficult for the family as they are asked to accept a ‘new concept of death’. The accepted concept and image of death involves a cold, lifeless body without a heartbeat; however, in the case of brain stem death the family are presented with an image of a warm patient with a heart beat who appears (due to the ventilator) to be breathing. Therefore, the visual message is one of life but the verbal message is one of death. In such cases denial is often enhanced and relatives must struggle to understand and accept the situation. Denial may be particularly acute in the case of an intracerebral bleed where there is no outward sign of injury or trauma.

Clear communications must ensue, the core message being that there is no hope of recovery. Irreparable damage has occurred and, in the case of brain stem death, the brain has died – death of the brain stem is death of the person.

When to offer donation

It is damaging to approach the family too early, as trust may be lost. Several studies examined the reasons for relatives’ refusal (for example, Simpkin et al. 2009) and noted that refusal could be attributed to several reasons, including concern about protecting the dead body, perceived quality of care during the current episode, timing of the request and a limited understanding of brain death. It was recognised as being important for the family to have accepted that death has occurred before donation is offered, so to inform the family of the death and to request donation at separate meetings. The timing of the request and the skill of the person making the request were seen to have the greatest positive impact on gaining consent for donation.

Who should offer donation?

All studies report that the person who has established a trusting relationship with the family is the most appropriate person to offer donation. It is important that the requestee has a positive view of donation and can offer it in a positive way.

How to offer donation

There are no ‘right’ words; each situation is unique and families will have their own individual responses. The family should be asked if they have any objection to donation rather than for permission to proceed. Some families will require time to consider their decision. Many relatives will have additional questions concerning the process of donation and its implications at this time. The family may require reassurance on the following issues:

- The donor will feel no pain.

- There will be dignity and respect throughout the donor surgery.

- The body will not be grossly mutilated or disfigured.

- The surgical wound will be sutured.

- They can view the body after surgery and the funeral will not be delayed.

The specialist nurse for organ donation works closely with other healthcare professionals to answer further questions and to facilitate the wishes of the family. It can be reassuring to the family that he or she will be present throughout the surgery and at the end to oversee and continue care. They will also ensure that the bereaved can see the deceased after surgery in the chapel of rest if this is their wish.

Unconditional gift

It is important to stress that organ donation is a voluntary ‘unconditional gift’. One case, much publicised, reported that the bereaved had stated that the organs ‘must only be given to white recipients’. Such a condition is totally unacceptable and there is now legislation that prohibits the placing of any conditions when agreeing to organ donations.

Continuing care after donation

Letters of thanks containing brief anonymous information concerning the transplant recipients are given or sent to the donor family after the donation. Further help and support are also offered. Many families state that the news of the successful transplants is a source of comfort. More recently, transplant coordinators have arranged meetings between donor families and recipients. Such meetings have been requested by both parties and have followed careful counselling and preparation to ensure the willingness of all individuals involved.

Refusal to donate

As part of recent measures to improve organ donation rates in the United Kingdom, an audit of potential donors in all UK intensive care units and emergency departments commenced in 2003 and was updated in 2009. The aim of the audit is to determine the number of potential organ donors. Results from the report for 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012 indicate that 91% of patients who met the criteria for donation after brain death (DBD) were referred as potential donors, however only 53% of patients meeting the criteria for donation after circulatory death (DCD) were referred. Of the families approached regarding potential organ donation the report cites the following as the main reasons for refusal of consent:

- Patient stated in the past they did not wish to be a donor (16.4%).

- Family were not sure the patient would have agreed to donation (16.2%).

- Family did not want surgery to the body (11.9%).

- Family felt it was against their religious/cultural beliefs (9.1%).

Further analysis of the results of the audit show that the age and gender of the potential donor has little impact on the refusal rate, but relatives of ethnic minority groups are more than twice as likely to deny consent than those of white potential donors (NHSBT 2012).

Refusal rates at this level represent a desperate lost potential. Therefore, it is vital that information programmes to allay fears and to present the successes of transplantation continue. It is also helpful to implement education for healthcare staff to examine the issue of requesting donation so that personnel will feel comfortable when offering this option of hope to the family.

Transplant coordinator groups have introduced workshops on breaking bad news and the approach for donation for nursing and medical colleagues working in intensive care and emergency departments. Such workshops use informed actors and provide a forum and a safe environment for staff to examine sudden traumatic death, the reactions of relatives and responses that will facilitate the approach for donation.

If the family agree to donation, the ventilation continues and the preparations for the donor surgery are made, but if the family refuse donation then ventilation will cease.

It is always helpful for the family if the deceased carried a donor card, was registered as a donor on the National Register or had discussed the issue with them. Most families want to fulfil the wishes of their loved one and if they know the thoughts of the deceased with regard to donation, then the question and decision are no longer difficult for them.

Clinical care of a potential organ donor

Brain-stem death results in changes to normal homeostatic mechanisms; such changes will ultimately result in cardiac arrest. Once permission has been given for donation it is important to stabilise the condition of the donor to ensure optimal condition of the organs for transplantation. The care can be very complex and is outside the scope of this book; but further reading can be found in ICS (2004).

The role of the specialist nurse for organ donation

All renal transplant centres depend on local organ donation specialist nurses. They are senior practitioners who offer a 24-hour service to intensive care units with regard to organ donation. The role of the specialist nurse at the time of donation is to offer:

- advice regarding suitability of a potential organ donor;

- advice regarding donor clinical care;

- advice and/or help with the approach to relatives;

- organisation of the organ donation procedure and surgery;

- support of the family and staff.

Organisation of the organ donation procedure and surgery

The specialist nurse will usually attend at the donor hospital to offer advice and support to the donor family and critical care staff. Organisation of the organ donation is complex and the specialist nurse will attempt to make all arrangements with a minimum of distress to the donor family and the critical care staff. The majority of organ donations today are multiple donations and it is the specialist nurse who organises the necessary blood and clinical tests, liaises with the heart, liver, renal and ophthalmic teams and arranges the donor surgery (Box 10.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree