Marion Gentul By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. List and describe the types of health insurance. 2. List and describe the major reimbursement methodologies. 3. Describe different prospective payment systems and the settings in which they are used. 4. Identify and explain the major components of the UB-04 (CMS-1450). 5. Identify and explain the major components of the CMS-1500. 6. Explain the role of the coder in reimbursement and data quality. 7. Describe the revenue cycle and the role of coding in the revenue cycle process. admission denial ambulatory payment classifications (APCs) billing capitation case management case mix case mix index (CMI) charge capture Chargemaster charges claim coding compliance plan continued stay denial co-insurance copay deductible Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) discharge planning discounted fee for service encounter form entitlement programs fee for service fee schedule fiscal intermediaries flexible benefit account guarantor group plan group practice model HMO grouper health maintenance organization (HMO) indemnity insurance independent practice association (IPA) model HMO insurance insurer local coverage determination (LCD) Major Diagnostic Categories (MDCs) managed care maximization Medicare administrative contractor (MAC) Medicare Code Editor (MCE) modifier National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) national coverage determination (NCD) network Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) optimization outlier payment patient financial services patient assessment instrument (PAI) payer preferred provider organization (PPO) premium principal diagnosis principal procedure prospective payment system (PPS) Prospective Payment System (PPS) blended rate provider number Quality Improvement Organization (QIO) Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) reimbursement relative weight (RW) reliability resource-based relative value system (RBRVS) Resource Utilization Group (RUG) revenue code Revenue Cycle Management (RCM) resource intensity risk self-pay staff model HMO superbill Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA) third party payer Title XIX of the Social Security Act Title XVIII of the Social Security Act TRICARE usual and customary fees (UCFs) utilization review (UR) validity working MS-DRG wraparound policies Patients and providers were, historically, the two main parties involved in a health care relationship. Patients were free to seek whatever services they were able to afford, and providers could charge whatever the market would bear. This one-on-one relationship has been split into a multiparty, complex system. The following section explores this system. The party (person or organization) from whom the provider is expecting payment for services rendered (reimbursement) is called the payer. The payer is frequently an insurance company. It may also be a government agency, such as Medicare or Medicaid. The term reimbursement is something of a misnomer. It is generally used today to refer to the payment provided to a physician or other health care provider in exchange for services rendered. With respect to reimbursement in health care, one of following two reimbursement scenarios typically occurs: In a hospital setting, for example, a hospital provides services and supplies to a patient, thus incurring costs, under the assumption that it will be reimbursed for these costs after the patient has been discharged. The payer is billed at a later date. Insurance plans today do not typically require a patient to reimburse a hospital and then submit a claim to the insurance company for reimbursement. Patients without some form of third party payment relationship are called self-pay patients and are billed directly for services rendered. Reimbursement takes many different forms. In the past, it was not uncommon for a physician to be “paid in kind.” For example, a physician might have made a house call to treat a patient and then received chickens as compensation. These types of bartering arrangements were mutually acceptable to both physician and patient. Reimbursement today is generally monetary, especially for hospitalization services, but in many parts of the world and in the United States, bartering for health care services is common and acceptable. Historically, a physician did not necessarily receive the payment that he or she charged but rather the payment that the patient thought the physician’s services were worth. In the early twentieth century, this practice changed to paying what the physician charged. More recently, the amount of compensation given to the physician or health care provider is decided not by the patient or physician but by the third party payer. Third party payers have assumed the risk that a particular group of patients will require health care services and therefore incur the cost of paying for the services. In the following discussion, reimbursement is categorized according to the control that the health care provider exerts over the fees that are charged. Insurance is a contract between two parties in which one party assumes the risk of loss on behalf of the other party in return for some, usually monetary, compensation. The insurer receives a premium payment, often on a monthly basis, and in return it pays for some of all of the cost of health services. Insurance companies have existed for centuries. Notably, Lloyds of London insured cargoes on merchant ships, which were frequently subject to loss from piracy, inclement weather, and other catastrophes. The beginnings of insurance in health care date only to the mid-nineteenth century, when companies insured railroad and paddleboat employees in the event of catastrophic injury or death. A lump sum was paid to an employee or employee’s family after such an event. The origins of modern health care insurance, as we know it today in the United States, begin during the Great Depression in the 1930s. A decline in health care industry income prompted the development of hospital-based insurance plans. For a payment of a small sum, a hospital guaranteed a specific number of days of hospital care at no additional charge. The most successful of these plans was developed at Baylor University by Justin Ford Kimball (Sultz, Young, 2006; Blue Cross, 2011)—Baylor’s plan eventually became the model for what we know today as Blue Cross Plans. Table 7-1 contains definitions of several terms that are useful during any discussion of health insurance. TABLE 7-1 TERMINOLOGY COMMON TO HEALTH INSURANCE POLICIES In the early days of the industry, health care insurance was paid for by the recipient, sometimes through the employer, union, or other organization. In the original Baylor University scheme, teachers paid $0.50 a month, which entitled them to 21 days of hospital care should they need it (Sultz, Young, 2006). The insurance company became a third party payer in the relationship between the provider and patient. Many patients have more than one payer. The primary payer is billed first for payment. A secondary payer is approached for any amount that the primary payer did not remit, and so on. For example, patients who are covered by Medicare may have supplemental or secondary insurance with a different payer. The physician first sends the bill to Medicare. Any amount that Medicare does not pay is then billed to the secondary payer. Ultimately, the patient is financially responsible for payment of services that he or she has received. Depending on the type of insurance, the patient may have automatic responsibilities, such as copays, co-insurance, or deductibles. A copay is a fixed amount that a patient remits at the time of service. Copays typically vary according to the service rendered. For example, a copay may be $20 for a physician visit and $100 for an emergency department visit. Co-insurance is the percentage of the payment for which the patient is responsible. The payer may have 80% responsibility for the payment, and the patient 20%. A deductible is a fixed amount of patient responsibility that must be incurred before the third party payer is responsible. For example, if the patient has a $500 deductible, then the patient must spend $500 for health care services first. After $500 is expended, the third party payer will begin to reimburse for services rendered. In all cases, payment by third party payers depends on the contractual relationship between the third party and the patient. Third party payers will reimburse only for services that are covered in that contract. If the patient is a dependent, a person other than the patient may be ultimately responsible for the bill. The person who is ultimately responsible for paying the bill is called the guarantor. For example, if a child goes to the physician’s office for treatment, the child, as a dependent, cannot be held responsible for the invoice. Therefore the parent or legal guardian is responsible for payment and is the guarantor. Figure 2-6 lists financial data required by a health care provider. After World War II, employers began offering their employees certain benefits, including health insurance. Benefits packages became useful in enabling employers to hire and retain employees. Employees benefited because they did not need to spend money on premiums, and employers benefited because health insurance benefits were a relatively low-cost way to attract quality employees. Insurance companies benefited from an increased client base. However, this thrust a fourth party into the provider/patient relationship: the employer. Originally, the focus of insurance was on the coverage of services at the health care provider’s fee. If the provider raised the fee, the insurance company raised its premiums to cover these fees. As health care costs increased, premiums also increased dramatically, becoming too expensive for many employers to pay in full. Currently, many employers pay only a part of the premiums, with employees bearing the rest of the expense. Health care providers render services for which they expect to be fairly compensated. Patients need these services, but their high cost is largely unaffordable. Insurance companies are willing to assume the risk of having to pay for expensive services, but they cannot spend more than they earn in premiums. To avoid this, insurance companies try to balance their risk by insuring a large number of patients, many of whom will likely not need health care services at all. This assumption of risk is the foundation of the concept of insurance. Insurance companies negotiate contracts with both the patient (usually via the employer) and the provider. Each party would like to minimize its financial loss. The provider wants to minimize the chances of receiving less payment for services than it costs to provide those services. The insurance company wants to minimize the potential loss of paying out more for health care than it receives in premiums. The patient wants to minimize the cost of health care. Each party negotiates contracts and attempts to minimize its risks by taking all potential treatment costs and circumstances into consideration. Insurance companies serve the public by assuming the risk of financial loss. Automobile owners probably have auto insurance. They pay periodic premiums to the auto insurance company, which in turn covers all or part of the costs incurred in an accident. The auto insurance company, although assuming the risk of financial loss in the event of an accident, is gambling that its customers will not have one. In fact, it goes to great lengths to predict the likelihood of accidents in certain populations, geographical areas, and types of vehicles. If one pays $1000 per year in auto insurance premiums for 40 years and never has an accident, then the insurance company keeps the $40,000 (plus interest) accumulated over the life of the policy. If the auto insurance company insures a very large number of drivers, in theory and under normal circumstances, only a small percentage of them will ever have a costly accident. In some states, auto insurance companies are permitted to choose which drivers they wish to insure. Obviously, they would prefer to choose drivers with good driving records and no history of accidents. In other states, insurers may not pick and choose and must offer insurance to anyone who applies for it. This requirement raises the risk that the insurer will be required to pay for the costs of accidents and resultant settlements, in turn raising the cost of auto insurance for all, unless the premiums of the high-risk drivers are increased significantly to compensate. Health insurance works in a similar way. In a system in which employers provide most private insurance plans, health insurers have fewer ways to limit their exposure to “high-risk” patients. Nevertheless, this model remains attractive to health insurers: they want to cover large numbers of individuals so that the cost of very expensive care is offset by premiums collected from many others requiring less expensive care. The health insurer wants to cover large numbers of individuals so that the risk that someone will require expensive medical care is offset by the large numbers of individuals who require less expensive care (Figure 7-1). When the employer pays the cost (premium) of the health care insurance, it is the employer who negotiates what will be covered. Although there are some federal mandates regarding what must be covered and under what circumstances, in general it is the employer’s decision—generally based on what the employer can afford to pay in premiums for the group. Group plans, such as those negotiated through employers, consist of pools of potential patients (in this case, employees) whose risk can be averaged by the third party payer. In an environment of rising health care costs, increases in payments to providers trigger increases in premiums to the insured. But the insertion of the employer into the patient/provider relationship has at least two effects: loss of control over the choice of individuals to cover and loss of total freedom to raise premiums. The insurer is pressured to accept all employees, reducing the insurer’s ability to control risk. If one individual cancels a policy, the financial impact is far less dramatic than if an employer cancels a group policy. In this way, an employer can pressure the health insurer to keep premiums low so as not to lose the employer’s account. There are many different insurance plans, with an almost endless variety of benefits and reimbursement rules. Plans may set dollar-amount limits or usage limits on the benefits used in a certain amount of time. Nevertheless, plans fall into one of two basic categories: indemnity and managed care. Managed care plans are further divided into two major types: preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The major features of these plans are discussed later in this chapter. The plans differ in the relationships among the physician, patient, and insurer and affect the way patients access care. A typical insurance arrangement requires the patient to pay the physician or other health care provider and then submit the bills to the insurance company for reimbursement. Under the terms of the insurance contract is a list of services for which the insurance company agrees to pay, called the covered services. If the patient receives a covered service, then the insurance company reimburses the patient. Some insurance companies pay 100% of the cost of certain covered services and a lower percentage of the cost of other covered services. This type of insurance, called indemnity insurance, was the predominant type of health insurance for many years, and patients generally paid the premiums. Indemnity insurance plans still exist, but managed care plans have become more prevalent. An important feature of indemnity insurance is the deductible. A deductible is the amount for which the patient is personally responsible before any insurance benefits are paid. If a patient incurs medical expenses of $5000, and her policy includes a deductible of $300, she pays the first $300 out-of-pocket (from her personal funds). The insurer then pays the portion of the remaining $4700 covered by the policy. After that, the patient is responsible for any amount not covered by her policy. Depending on the insurance company plan, a deductible could apply for every encounter, every visit, or every hospitalization, or it could be applied on an annual basis. If the insurance plan covers a whole family, the deductible could be per person or per family. One effect of the deductible is that routine health care costs often do not exceed the deductible amount. In these instances, the insurance company ultimately covers and pays for only unusual or extraordinary expenses. Conversely, indemnity contracts often specify limits for certain covered services. If the benefit limit is $3000 for physician office visits and the patient’s care (after the deductible) is $4000, then the patient is responsible for the additional $1000. Indemnity insurance plans led to an increase in the amount of money spent on health care. In a simple physician-patient relationship, the patient bears the cost of the care and therefore has some influence on the fees. Individuals may choose not to go to the physician in the first place because they feel the fee is too high and they cannot afford it, or they might be able to afford only some services. But because indemnity insurance plans, even with the deductible, reduce the out-of-pocket expense to the patient, they increase the likelihood that the services of the provider will be used regardless of the fees. Consequently, the number of people using health care services has increased. In addition, if the insurance company reimburses for services without reviewing the need for those services, then physicians have no incentive to be conservative in their diagnostic and treatment plans. The costs have risen still further with advances in diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, many of which are extremely costly in their initial phases. As these technologies become more widely used, the cost of providing health care increases. In addition to the technology-driven expenses, health care costs have risen because a small portion of the health care community provided an excessive number of services to their patients. Two radiographs may have been taken when one would have sufficed, or computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was used when a simple radiograph would have been sufficient to achieve the same diagnostic goal. Often it is not entirely the provider’s fault when these excesses occur. Some patients may feel entitled to the newest technologies even if they are not necessary, and so they pressure their physicians into ordering them. The physician may not want to lose the patient’s business or to be subjected to a lawsuit for failure to use all available diagnostic means. To meet the rising costs of health care, insurance companies raised health care premiums. Eventually, some employers could no longer afford to offer health insurance as a benefit. Many employers began shifting the cost of insurance to the employees. Other employers solved the escalating premium problem by hiring more part-time employees, who were not eligible for benefits. Still other employers hired outside contractors to perform noncritical functions. With costs rising, health insurance companies had to find ways to control their expenses. Certain steps, such as imposing higher deductibles and strictly limiting the number and types of covered services, could help lower their costs. However, insurance becomes less attractive under these circumstances, and insurance companies want to remain in business. The insurance industry responded to these circumstances and factors, opening the door to the concept of managed care plans. The term managed care, in general, refers to the control that an insurance company or other payer exerts over the reimbursement process and over the patient’s choices in selecting a health care provider. In the pure physician-patient relationship, the patient uses the physician of his or her choice. The patient arrives at the office with a medical concern, and the physician determines a diagnosis and develops a treatment plan. The patient agrees (or declines) to undergo the treatment plan, the physician bills the patient, and the patient pays the physician. Under managed care, the insurer (payer) and the health care provider have a contractual arrangement with each other. The providers participate in a particular managed care plan, which means that they are under contract with the managed care plan insurer to provide services to the insurer’s patients. Managed care patients are referred to, depending on the insurer, as members, enrollees, or covered lives. The primary insured member is the subscriber, with those covered under the subscriber’s policy referred to as dependents or additional insured. The insurer’s patients must choose their providers from those participating in the managed care plan. The scope of services paid for is determined by the insurer’s contract with the subscriber (or the subscriber’s employer or group manager). Decisions about the medical necessity of specific services are made by the managed care organization. For example, a physician may write an order for a blood test to determine whether the patient has a vitamin D deficiency. The managed care organization may have determined that it will pay for vitamin D blood tests only if the patient is known or suspected to have a bone loss condition, such as osteopenia or osteoporosis. In a managed care scenario, the patient goes to the primary care physician (PCP), whom the patient has chosen from a list of participating physicians. The physician diagnoses and treats the patient according to the guidelines from the managed care plan. The patient may pay the physician a small copay. The physician bills the managed care insurer directly for the visit. The managed care insurer may refuse to pay the physician if the physician does not obtain preapproval or authorization for some treatments, such as hospitalization. If the patient sees a physician outside the plan, the patient may not be covered at all and may have to pay the physician himself or herself. In many instances, the patient cannot go to a specialist directly but must visit the PCP first. After examination and discussion with the patient, the PCP must justify the necessity for the involvement of a specialist and must refer the patient to a specialist participating in the plan. Managed care organizations seek to reduce costs by controlling as much of the health care delivery system as possible. The underlying rationale for managed care is to reduce overall costs by eliminating unnecessary tests, procedures, visits, and hospitalizations through financial incentives if the plan is followed and financial penalties or sanctions if the plan is not followed. A major controversy in this strategy lies in the definition of what constitutes unnecessary health care and who makes this determination. Traditionally, physicians have determined the care that they provide to patients, whereas managed care has shifted that determination somewhat to the insurer. To emphasize: The managed care organization does not dictate what care will be rendered; it dictates what care it will pay for. It is the prohibitive cost of care that drives a patient to elect only that care for which third party payment is available. It should be noted that managed care plans employ physicians who assist in making determinations. For example, many managed care insurers did not consider preventive care to be necessary and would not pay for it. It was only through years of study, investigation, and trial and error that they discovered that preventive care was one of the best ways to reduce health care costs. This fact is particularly salient with regard to obstetrical care. The costs of treating a pregnant woman through prenatal testing, education, and regular examinations, with the goal of delivering a healthy newborn, are significantly less than those of treating a newborn or new mother with complications that could have been prevented or treated earlier at less cost. The same holds true for dental care. Theoretically, if teeth are examined and cleaned routinely, expensive fillings and root canal treatments will not be needed because the dentist will help detect and treat those problems early. Individuals who change jobs are often forced to find new health care providers if their previous physicians are not included in the new insurer’s plan. The same may be true if the employer changes insurers. Patients who live at the outskirts of a plan’s primary service area may be required to travel unacceptably long distances to receive covered health care services. Physicians may feel a loss of control in the treatment process. They are sometimes frustrated by the emphasis on medical practice standards, what some call “cookbook medicine,” and resistance to what they may see as individualized, alternative approaches of care. Managed care organizations focus heavily on statistical analysis of treatment outcomes and scrutinize physicians whose practices appear to vary significantly from the norm. Managed care has forced physicians to become more aware of and active in managing their own resources by employing reimbursement methods other than fee for service that shift some financial risk to the physician. Despite controversy and criticism, managed care has become an important presence in the health care arena. Managed care takes a number of different forms, and there are many variations in the relationship among managed care organizations and physicians and other health care providers who deliver their services. At the heart of managed care is the idea that the insurer can gain better control over cost of health care by delivering the services directly. The U.S. Congress supported this concept with the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973, which encouraged the development of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and mandated certain employers to offer employees an HMO option for health care delivery. An HMO is a managed care organization that has ownership or employer control over the health care provider. Essentially, the HMO is the insurer (payer) and the provider. Members must use the HMO for all services, and the HMO will generally not pay for out-of-plan (also called out of network) services without prior approval. In some plans, approval to obtain health care services outside the plan is granted only in emergency situations. In the staff model HMO, the organization owns the facilities, employs the physicians, and provides essentially all health care services. In a group practice model HMO, the organization contracts with a group or a network of physicians and facilities to provide health care services. Finally, in an independent practice association (IPA) model HMO, the HMO contracts with individual physicians, portions of whose practices are devoted to the HMO. Regardless of the HMO model, an HMO generally does not reimburse for services provided by providers who are not in the HMO’s network. A preferred provider organization (PPO) is another managed care approach in which the organization contracts with a network of health care providers who agree to certain reimbursement rates. It is from this network that patients are encouraged to choose their primary care physician and any specialists. If a patient chooses a provider who is not in the network, the PPO reimburses in the same manner as an indemnity insurer: for specified services, with specific dollar amounts or percentage limits, and after any deductible is paid by the insured. A PPO is a hybrid plan that gives patients the option of choosing physicians outside the plan without totally forfeiting benefits. In addition, PPOs may offer patients a certain degree of freedom to self-refer to specialists. For example, some plans allow patients to visit gynecologists and vision specialists directly, without referral from the PCP. Although not specifically a type of insurance, self-insurance (or self-funded insurance) is an alternative to purchasing an insurance policy. The term self-insurance should not be confused with patients who “self-pay” or those who have no insurance or coverage plan at all. Self-insurance is really a savings plan in which an individual or employer puts aside funds to cover health care costs. In this way, the individual or company assumes the financial risk associated with health care. Because the assumption of risk rests with the company or the individual, this is not so much a type of insurance as it is an alternative to shifting the risk to an insurer. An employer may choose to self-insure for all health care benefits, or it may self-insure to provide specific benefits that its primary insurance plan does not cover. For example, an insurance plan may cover preventive care, hospital and physician services, and diagnostic tests. However, it may not cover vision or dental care. The employer may designate to each employee a certain dollar amount with which the employee may then be reimbursed for these other services. Ordinarily, if the annual dollar amount is not spent, it is lost to the employee. Because the issue of confidentiality is so important, employers may choose to contract with an insurer to process health care claims, even if the employer self-insures. Individuals may self-insure by saving money on a regular basis through their employer. These savings are designated for health care expenses. One formal plan that enables individuals to save in this manner is a flexible benefit account (or medical savings account). A flexible benefit account provides the individual with a savings account, usually through payroll deduction, into which a set amount determined by the employee can be deposited routinely. These funds can then be drawn on to pay out-of-pocket health care and some child-care expenses. The advantage to a flexible benefit account is that the funds are withdrawn from the individual’s salary on a pretax basis, thereby reducing the individual’s income tax liability. The disadvantage is that nondisbursed funds are forfeited at the end of the year. Table 7-2 summarizes the four types of insurance that have been discussed. TABLE 7-2 SUMMARY OF HEALTH INSURANCE RELATIONSHIPS In Chapter 1, a collaborative process of patient care involving the physicians, nurses, and other allied health professionals was described. This patient care plan is more than just a series of instructions or recommendations for an individual patient. Clinicians typically follow established patterns of care that are based on experience, successful outcomes, and research. The formal description of these patterns of care is the clinical pathway. Each discipline has a specific clinical pathway that describes the appropriate steps to take, given a specific diagnosis or a specific set of signs and symptoms and based on the answers to critical questions. For example, a patient with high blood glucose (hyperglycemia) must be tested to determine whether the patient is diabetic. If the patient is diabetic, further studies will identify whether the condition is insulin dependent or not. The physician will prescribe the appropriate medications and other regimens on the basis of that determination. Nursing staff will assess the patient’s level of understanding of his or her condition and take the appropriate steps to educate the patient and possibly the family. Figure 7-2 illustrates a clinical pathway. The responsibility for patient care rests with the provider, but often multiple providers, and possibly multiple facilities, are involved in a patient’s care. From the payer’s perspective, case management is necessary to coordinate the approval of and adherence to the care plan. From the provider’s perspective, case managers are necessary to facilitate the continuity of care. Thus a patient may have multiple case managers working from different perspectives, all helping to ensure that the patient is cared for appropriately and efficiently. Understanding clinical pathways and payer issues enables a facility to evaluate patient care, control the use of facility resources, and measure the performance of individual clinical staff. In a hospital, the utilization review (UR) department works closely with all health care disciplines involved in caring for a patient who has been admitted. UR staff members (also known as case management personnel) are responsible, with physician oversight, for performing an admission review that covers the appropriateness of the admission itself, certifying the level of care for an admission (e.g., acute, skilled nursing), monitoring the intensity of services provided, and ensuring that a patient’s length of stay is appropriate for that level of care. UR staff members may have daily contact with a patient’s insurance company during the patient’s admission to verify that the correct level of care payment will be received for the anticipated length of stay. UR staff may also make provisions for aftercare once the patient is discharged; this is called discharge planning. For example, suppose a patient with Type 1 diabetes mellitus is admitted because the patient performed a self-check at home and could not control his blood glucose level even while taking the prescribed amounts of daily insulin. UR staff members will be notified that the patient has been admitted, and they will perform an admission review. This admission review entails an evaluation of the patient’s medical record, including physician orders and any test results. In some cases, the admission will be deemed unnecessary. The admission might be unnecessary if the patient’s blood glucose levels were all normal on admission. At that point, UR staff members would not certify the admission for reimbursement; this is called an admission denial. If UR staff members deem the admission necessary, they will certify the admission. UR staff may contact the patient’s insurer, verify the diagnosis of uncontrolled Type 1 diabetes mellitus, and determine that the anticipated length of stay for that diagnosis is 2 to 3 days. The insurer agrees to reimburse the hospital for 3 days of acute care as certified by UR staff. During the hospitalization, UR staff members will discuss the aftercare, or discharge plan, with the attending physician. In this case, perhaps more home health care services are warranted. On the third day, the patient is expected to be discharged. If the patient is not discharged on day 3, members of the UR staff must review documentation and discuss the case further with the physician to justify additional hospitalization. If the additional days are not justified by the documentation in the health record, the additional days may not be reimbursed by the insurer; this is called a continued stay denial. In these instances, the patient will be notified that he or she no longer needs to be in the hospital, that the insurer will not reimburse the hospital for any additional costs, and that the patient is responsible for all further costs. When a continued stay denial occurs, the physician is also notified. The physician will either concur with the continued stay denial and discharge the patient or provide documentation justifying the additional care. Although the United States does not have universal health care (i.e., government-subsidized health care for all citizens), the various levels of government do serve as the largest payer for health care services. Because eligibility for certain government-sponsored programs is automatic, being based on age, condition, or employment, they are called entitlement programs rather than insurance. The U.S. government has historically allocated funds for the benefits of specific populations. In the case of health care, target populations of chronically ill or indigent patients have received low-cost or free health care. Until the 1960s, funding was not entirely predictable and health care providers were often required to provide a certain amount of charity care. In addition, large groups of individuals with limited incomes were not eligible for federal assistance. The federal government took the plunge in the mid-1960s with the enactment of legislation that made it the largest single payer in the health care industry: Title XVIII and Title XIX of the Social Security Act, which established the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In addition to Medicare and Medicaid, the federal government administers TRICARE (formerly called CHAMPUS), which provides health benefits for military personnel, their families, and military retirees. The federal government provides health services to veterans through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Veterans Administration (CHAMPVA) was created in 1973 to provide health services for spouses and children of certain deceased or disabled veterans. TRICARE, VHA, and CHAMPVA are service benefits, not insurance, and are included here to illustrate the extent of the federal government’s financial involvement in health care. (See the TRICARE and CHAMPVA Web sites for additional information.) Table 7-3 provides a summary of this involvement. TABLE 7-3 SUMMARY OF FEDERAL INVOLVEMENT IN HEALTH CARE The Indian Health Services (IHS) provides care for American Indians and Alaska Natives. The IHS provides a comprehensive health service delivery system for approximately 1.9 million American Indians and Alaska Natives who belong to 564 federally recognized tribes in 35 states (Indian Health Services, 2012). Title XVIII of the Social Security Act established the Medicare program in 1965. Originally enacted to provide funding for health care for older adults, Medicare has grown to include individuals with certain disabilities or with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Medicare represents more than 50% of the income of some health care providers. Medicare is an extremely important driving force in the insurance industry because many insurance companies follow Medicare’s lead in adopting reimbursement strategies. For example, if Medicare decides that a particular surgical procedure will be reimbursed only if is it performed in the inpatient setting (as opposed to ambulatory surgery), other insurance companies may choose to enforce the same rule. The Medicare program, although funded by the federal government and administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), does not process its own claims reimbursements. Reimbursements are processed by Medicare administrative contractors (MACs) located in different regions throughout the country. Medicare coverage applies in four categories: Parts A, B, C, and D. Part A covers inpatient hospital services and some other services, such as hospice. Part B covers physician claims and outpatient services. Part C is a voluntary managed care option. Part D, implemented in 2006, is a prescription drug program. Because there are limits to Medicare coverage, many beneficiaries choose to purchase additional insurance; such plans, called wraparound policies (supplemental policies), are aimed at absorbing costs not reimbursed by Medicare. Many end-of-life hospital stays generate costs in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Therefore wraparound policies can help preserve estates and save surviving spouses from financial ruin. Medicare may also be the secondary payer for enrollees who are still employed and covered primarily by the employer’s insurance plan. Medicare beneficiaries also may enroll in a Medicare HMO program, called Medicare+Choice. Different HMOs have contracted with the federal government under the Medicare+Choice program to provide health services to these beneficiaries. In 1965, Congress enacted Title XIX of the Social Security Act, which created a formal system of providing funding for health care for low-income populations. Also administered by CMS, Medicaid, which is sometimes also called “Medical Assistance,” is a shared federal and state program designed to shift resources from higher-income to lower-income individuals. Funds are allocated according to the average income of the residents of the state. Unlike Medicare, which reimburses through fiscal intermediaries, Medicaid reimbursement is handled directly by each individual state. The reimbursement guidelines vary from state to state. Some states have contracted with insurers to offer HMO plans to Medicaid beneficiaries. Eligibility for Medicaid is determined by the individual states on the basis of the state’s income criteria. The federal government mandates that the following services be included in each state’s program: hospital and physician services, diagnostic services, home health, nursing home, preventive care, family planning, pregnancy care, and child care (see the CMS Web site for more information: http://www.cms.hhs.gov). With the federal government’s entry into the reimbursement arena, more citizens had access to health care services than ever before. The use of health care services rose accordingly, in turn driving health care costs upward at an alarming rate. Improved access for older adults meant better care and therefore longer life expectancy, which further increased costs. Thus cost containment became a critical issue. In the early 1970s, Professional Standards Review Organizations (PSROs) were established. PSROs conducted local peer reviews of Medicare and Medicaid cases for the purpose of ensuring that only medically necessary services were being rendered and appropriately reimbursed. Under the Peer Review Improvement Act of 1982, PSROs were replaced by Peer Review Organizations (PROs) through a federal law called the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA). TEFRA included a broad array of provisions, many of which had nothing to do with health care. For example, TEFRA raised taxes by eliminating previous tax cuts. In 2002, PROs were replaced by (or, more accurately, renamed) Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs). Many HIM professionals are employed in QIOs because certain specialized skills, such as data analysis and coding expertise, are necessary to support various federal initiatives delegated to QIOs. TEFRA’s impact on health care included a modification of Medicare reimbursement for inpatient care to include a case mix adjustment based on diagnosis related groups (DRGs). In 1983, Medicare adopted the Prospective Payment System (PPS), which uses the DRG classification system as the basis of its reimbursement methodology. Prospective payment systems (PPS) are discussed at length later in the chapter, but in the broadest terms, they operate on the assumption that patients with the same diagnoses will require roughly the same level of care, therefore consuming roughly the same resources and incurring roughly the same costs. Of course, the focus of treatment, patient length of stay, and the individuals involved in the care plan differ from setting to setting. Because prospective reimbursement systems are based on just these types of factors, different systems were developed for each health care setting.

Reimbursement

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Paying for Health Care

Types of Reimbursement

Insurance

History

TERM

DESCRIPTION

Benefit

The payment for specific health care services, or the health care services that are provided from an insurance policy or a managed care organization

Beneficiary

One who receives benefits from an insurance policy or a managed care program, or one who is eligible to receive such benefits

Benefit period

A period of time during which benefits are available for covered services, and which varies among payers and policies

Claim

The application to an insurance company for reimbursement of services rendered

Copayment (copay)

A fixed amount paid by the patient (or the subscriber to insurance policy) at the time of the health care service

Coverage

The health conditions, diagnostic procedures, and therapeutic treatments for which the insurance policy will pay

Deductible

A specified dollar amount for which the patient is personally responsible before the payer reimburses for any claims

Exclusions

Medical conditions or risks not covered by an insurance policy; preexisting conditions and experimental therapy are common exclusions to standard policies

Fiscal intermediary

An entity that administers the claims and reimbursements for a funding agency (i.e., an insurer or payer)

Insurance

A contract (policy) made with an insurer to assume the risk of paying some or all of the cost of providing health care services in return for the payment of a premium by or on behalf of the insured

Out-of-pocket costs

Costs not covered by an insurer, which are in turn paid by the patient directly to the provider

Payer

The individual or organization that is primarily responsible for the reimbursement for a particular health care service. Usually refers to the insurance company or third party

Premium

Periodic payments to an insurance company made by the patient for coverage under a policy

Preexisting condition

A medical condition identified as having occurred before a patient obtained coverage within a health insurance plan

Reimbursement

The amount of money that the health care facility receives from the party responsible for paying the bill

Rider

An adjustment to a policy that increases or decreases coverage and benefits, corresponding in an increase or decrease in the cost to the insured

Policy

Written contract detailing the coverage, benefits, exclusions, premiums, copays, deductibles, and other terms of the health plan

Subscriber

A person who purchases insurance

Third party payer

An entity that pays a provider for part or all of a patient’s health care services; often the patient’s insurance company

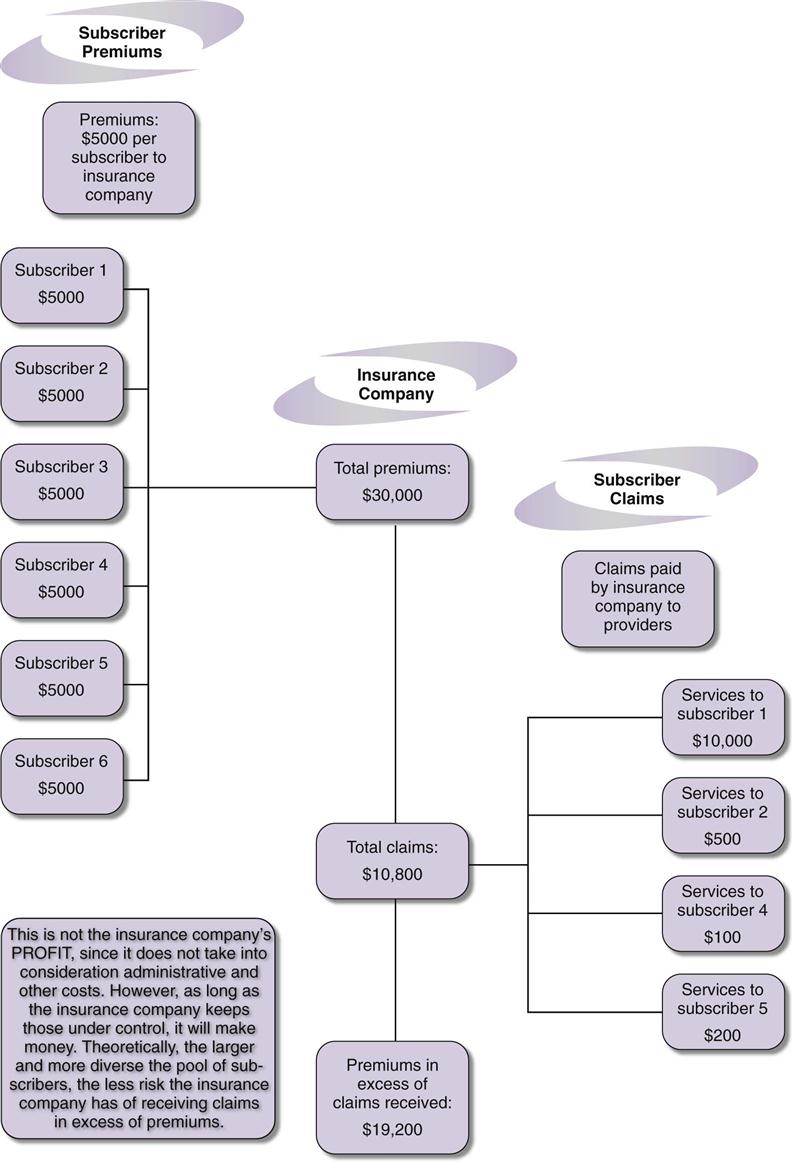

Assumption of Risk

Types of Health Insurance

Indemnity

Managed Care

Health Maintenance Organizations

Preferred Provider Organizations

Self-Insurance

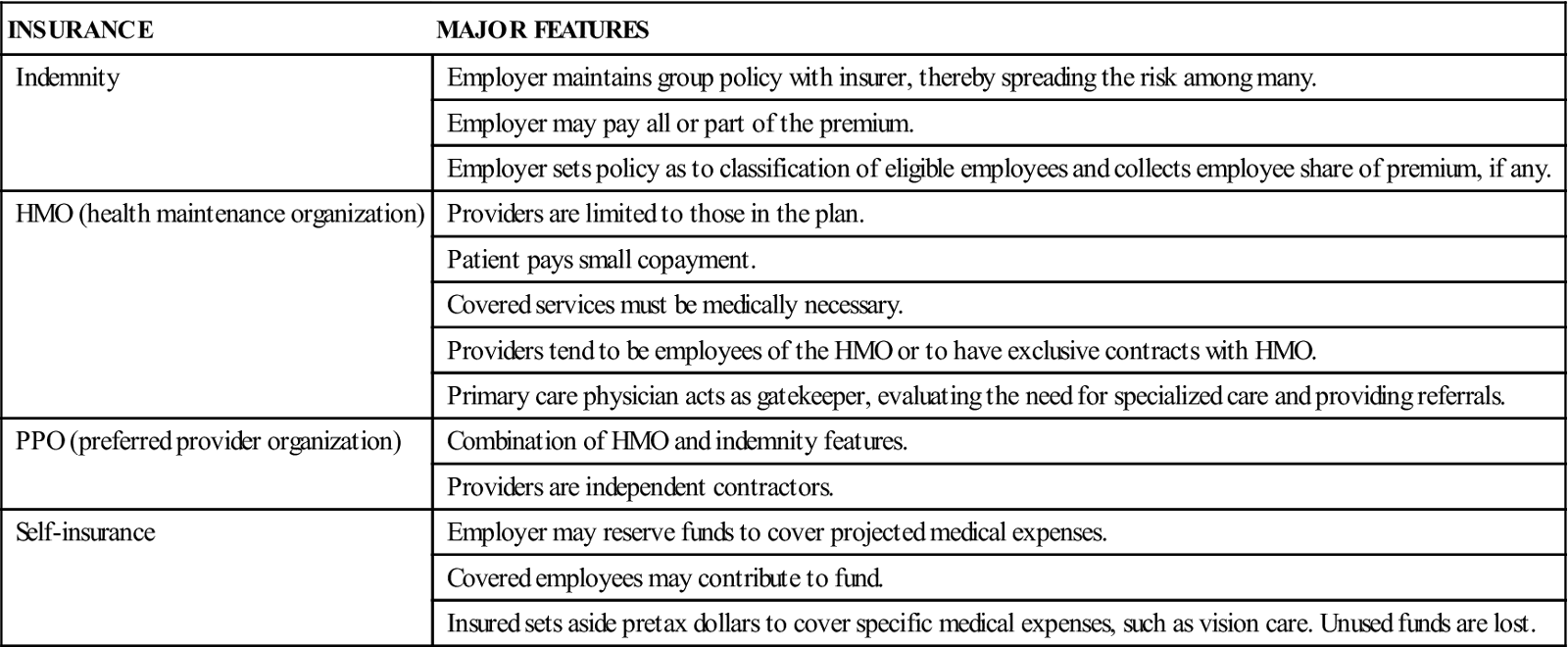

INSURANCE

MAJOR FEATURES

Indemnity

Employer maintains group policy with insurer, thereby spreading the risk among many.

Employer may pay all or part of the premium.

Employer sets policy as to classification of eligible employees and collects employee share of premium, if any.

HMO (health maintenance organization)

Providers are limited to those in the plan.

Patient pays small copayment.

Covered services must be medically necessary.

Providers tend to be employees of the HMO or to have exclusive contracts with HMO.

Primary care physician acts as gatekeeper, evaluating the need for specialized care and providing referrals.

PPO (preferred provider organization)

Combination of HMO and indemnity features.

Providers are independent contractors.

Self-insurance

Employer may reserve funds to cover projected medical expenses.

Covered employees may contribute to fund.

Insured sets aside pretax dollars to cover specific medical expenses, such as vision care. Unused funds are lost.

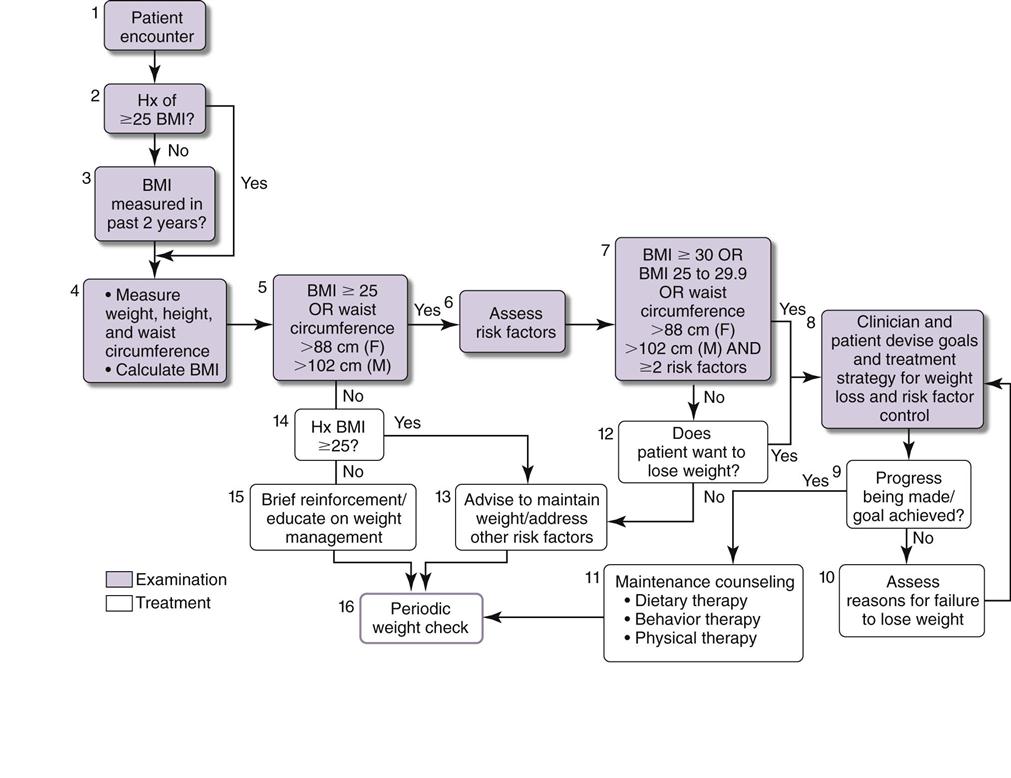

Clinical Oversight

Case Management

Utilization Review

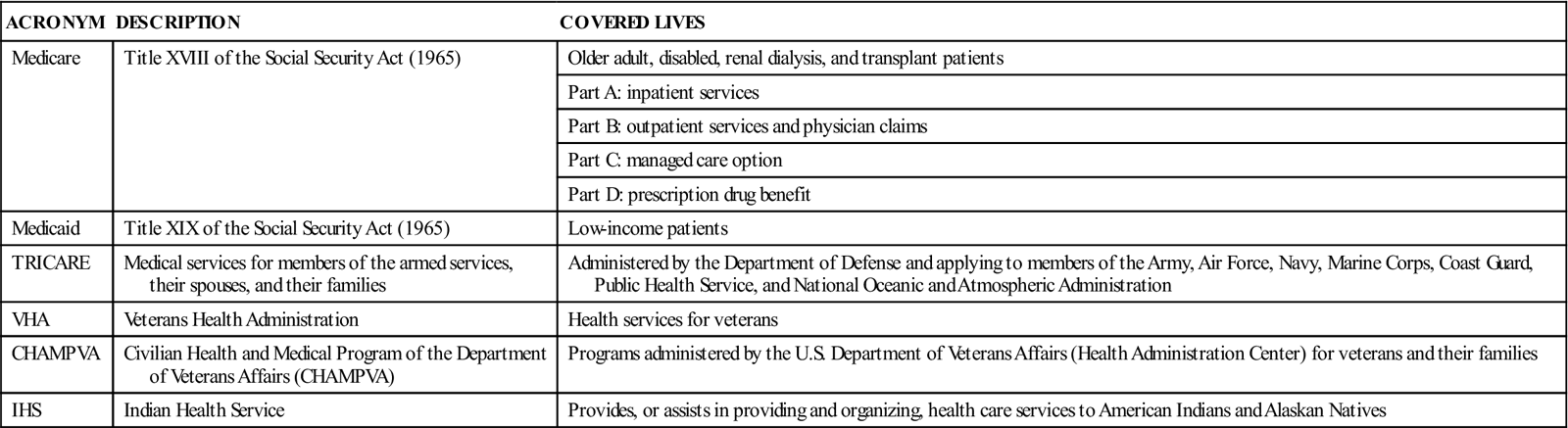

Entitlements

Federal Coverage for Specific Populations

ACRONYM

DESCRIPTION

COVERED LIVES

Medicare

Title XVIII of the Social Security Act (1965)

Older adult, disabled, renal dialysis, and transplant patients

Part A: inpatient services

Part B: outpatient services and physician claims

Part C: managed care option

Part D: prescription drug benefit

Medicaid

Title XIX of the Social Security Act (1965)

Low-income patients

TRICARE

Medical services for members of the armed services, their spouses, and their families

Administered by the Department of Defense and applying to members of the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Public Health Service, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

VHA

Veterans Health Administration

Health services for veterans

CHAMPVA

Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (CHAMPVA)

Programs administered by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Health Administration Center) for veterans and their families

IHS

Indian Health Service

Provides, or assists in providing and organizing, health care services to American Indians and Alaskan Natives

Medicare

Medicaid

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree