Functioning and disability

Body functions and body structures

Activities and participation

Contextual factors

Environmental factors

Personal factors

A person with a disability has intrinsic value that transcends the disability; each person is a unique holistic being who has the right and the responsibility to make informed personal choices regarding health and lifestyle. Patient-centered care focuses on the patient as the primary focus of care. Restoring an individual’s capacity to the highest level possible assists the person to resume roles such as homemaking, parenting, and gainful employment, thus offering many social, emotional, psychological, and financial returns to society.

Rehabilitation is an integral component of all care administered by all health care providers. Rehabilitation begins the moment a person seeks health care so that prevention is incorporated into the rehabilitation process. A major goal in educating all health care providers is to prepare them to “think rehab” from the moment of initial contact with the patient.

Comprehensive rehabilitation requires the active participation and collaboration of all members of the interprofessional team through ongoing communication, common patient-centered goals, and coordinated/timely treatment. Scheduled team conferences, informal discussion, a documented plan of care, and progress notes provide a means of communication. Multidisciplinary collaboration and management mean that all health team members collaborate to achieve specific, identified, mutual goals.

Patient-centered rehabilitation requires the active participation of the patient and family to achieve optimal rehabilitative potential. The patient must be motivated and actively involved in the rehabilitation process to achieve optimal outcomes.

Rehabilitation actively involves the patient’s family or significant others; they are the patient’s potential support systems and assist with the transition back to the home and community. Family members should be reached at their individual levels of understanding, taking into consideration their educational, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds to understand the rehabilitative goals and methods selected to meet these goals. The nurse usually interprets this information for the family, helping them to understand how they can best participate. In addition, the family is a rich source of information about the patient’s personality and lifestyle that will be helpful in the transition back to the community.

An individual patient and family evaluation is the basis to determine their ability to contribute to the rehabilitation process. All families cannot contribute in the same way or to the same degree. Because each family and patient present different strengths and needs, individual evaluation is necessary.

The patient experiences illness and disability within the context of his or her previous adjustment patterns. The strengths and weaknesses of the patient’s personality are essentially the same during illness. Team members must recognize the social and cultural influences that affect the patient’s adjustment patterns and acceptance of care.

Rehabilitation takes place within the context of the patient’s whole life: the sociocultural aspects of life, his or her job or vocation, family, home, place in the community, religion, and relationship to self. When illness strikes, family life is abruptly interrupted and altered. Illness affects not only the patient, but also the family. Therefore, rehabilitation includes the needs of the family.

Rehabilitation is a dynamic process with progress, plateaus, and setbacks. In relation to the rapid change in the acute care setting, rehabilitation progresses at a slower pace often with challenges along the way. Only through ongoing assessment and problem solving is achievement of patient goals possible.

Transitions in care include plans for continued rehabilitation services and care coordination. Options include acute or subacute inpatient rehabilitation, community re-entry, outpatient rehabilitation, or home health therapies. The patient and family are presented with various care alternatives and helped to evaluate the implications of each choice, including cost and health insurance issues. The patient and family actively participate in the decision-making process of discharge planning to the degree that they are able and willing to participate for a relatively smooth transition and adjustment.

Rehabilitative potential: dormant power for rehabilitation within a person that exists as a possibility that can eventually become actualized

Short-term goals: goals to be achieved in the immediate future (usually set for 1 week); discrete units or steps involved in the learning of a skill that must be achieved before more complex skilled acts can be accomplished; the steps through which long-term goals are achieved

Long-term goals: goals projected for completion in the distant future; can be considered the ultimate objectives of a rehabilitation program

Optimal goals: the rehabilitation goals that may be expected barring significant setbacks or complications

Realistic goals: goals that reflect a grounded and reasonable appraisal of the person and achievable outcome

Acute disability: a disability that has a finite duration and is completely resolved in a short period of time; reversible; temporary

Chronic disability: an ongoing disability that limits the person in some way; permanent; irreversible

Interdisciplinary practice model: health professionals working together to achieve measurable functional outcomes for people with disabilities

Multidisciplinary team rounds: activity in which the health professionals round together to assess and monitor progress, functional level, problems, and concerns on some scheduled daily or weekly basis; it provides data for further discussion at team meetings or patient care conferences

Family meetings: planned meetings with one or more health care professionals and family members to discuss patient progress, needs, and planning; recognizes the importance of the family in the rehabilitation of the patient, and helps to maintain open communication

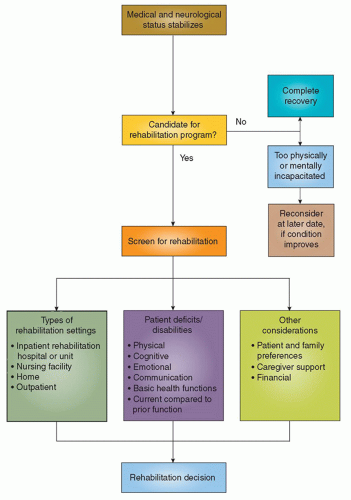

resources. In this complex health care environment, utilization of health care and cost are scrutinized. A key initial decision is whether the person can benefit from rehabilitation. Figure 11-1 summarizes the process of rehabilitation decision making. This information and figure are taken from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) clinical practice guidelines, Post-Stroke Rehabilitation (1995), but they are applicable to all initial and subsequent transitional rehabilitation decisions.5

promoting continuity of care and moving the plan forward. Because of the complexity of care and the numbers of people involved, it is easy for communications to break down. Therefore, planned, formal, patient-centered conferences are essential for the vitality of the process. Patient outcomes are measured using the FIM, Barthel Index, and other specific instruments.

CHART 11-1 Principles of Learning and Teaching | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Basic or personal ADLs (BADLs or PADLs): these are activities focused on self-care. They include bathing/showering, bowel and bladder management, dressing, eating (ability to chew and swallow), feeding (process of bringing food/drink to the mouth for consumption) functional mobility personal device care (e.g., hearing aids, glasses), personal hygiene and grooming, sexual activity, sleep/rest, and toilet hygiene. The ability to perform these activities vastly contributes to independent self-care.

Instrumental ADLs (IADLs): these are activities focused on interaction with the environment. These are activities that can be performed by another person on behalf of the individual if necessary. These activities include caring for others including pets, child rearing, communication device use, community mobility, financial management and maintenance, home establishment and management, meal preparation and cleanup, safety procedures and emergency responses, and shopping. Independence in these activities is a key marker for independence outside the home.

encouraging the patient to be as independent as possible in ADLs. Instituting exercise programs designed to increase ROM, teaching ADLs to a patient with a paralyzed limb, and helping a patient to relearn names of common objects are examples of restorative nursing activities. This framework can be kept in mind when planning and administering nursing care to address particular deficits.

CHART 11-2 Teaching the Patient with Cerebral Injury | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Impaired physical mobility

Risk for injury (from falls)

Risk for altered skin integrity

Fatigue

Activity intolerance

Depression

Pathologic fractures

Joint dislocation

Falls

The sensation of movement is learned and not the movement itself.

Every skilled activity takes place against a backdrop of basic patterns of postural control, righting, equilibrium, and other protective reactions.

When cerebral injury occurs, abnormal patterns of posture and movement develops that interfere with the performance of ADLs.

Abnormal patterns develop because sensation is diverted into the abnormal patterns; this diversion must be stopped to reinstitute control over the motor output in developmental sequence.

Eliciting the basic patterns of postural control, righting, and equilibrium is necessary, thus providing the normal stimuli while inhibiting abnormal patterns.

People are allowed to feel, and thus relearn, normal movement patterns and postures.

Reintegration of function of the two sides of the body is emphasized during movement, ADLs, and bed or chair positioning so that bilateral segmental movement will occur.

Proximal to distal positioning is recommended (tone in the limbs can be reduced from proximal points, such as the head, shoulder, or pelvic girdle).

Weight bearing is provided on the affected side to normalize tone. This includes its role in sitting, lying, or rising.

Tasks should begin from a symmetric midline position with equal weight bearing on the affected and unaffected sides.

Movement toward the affected side is encouraged.

Straightening of the trunk and neck is encouraged to promote symmetry and normalization of tone and posture.

Patients with hemiplegia should be positioned in opposition to the spastic patterns of flexion and adduction in the upper extremity and extension in the lower extremity.

The unconscious patient should be repositioned every few (e.g., 2 hours) hours around the clock. As consciousness is regained, independent movement in bed and participation in self-care activities are encouraged to maintain muscle strength and tone. Proper positioning should be taught to the patient if he or she has the cognitive ability to participate.

TABLE 11-1 PATTERNS OF MUSCLE RECOVERY IN HEMIPLEGIA

STAGE

NAME

ONSET

DESCRIPTION

I

Flaccidity

From the time of injury to 2 or 3 days after

No tendon reflexes or resistance to passive movement

II

Spasticity (late onset of spasticity indicates a poorer prognosis)

2 days-5 wks

Hyperactive tendon reflexes and exaggerated response to minimal stimuli

III

Synergy (flexion, then extension)

2-3 wks

Simultaneous flexion of muscle groups in response to flexion of a single muscle (e.g., an attempt to flex the elbow results in contraction of the fingers, elbow, and shoulder)

IV

Near normal, possible weakness, or slight incoordination may still be present (late return of tendon reflexes indicates a poor prognosis)

1 wk-6 mos

Control of voluntary movement; recovery occurs predictably from the proximal muscles of the extremity to the distal muscles (i.e., voluntary movement of the hand and foot is last to recover and tends to be weaker)

If spasticity is present, frequent repositioning is necessary. Splinting and casting to inhibit tone may be ordered and applied by a physical therapist (PT).

Any restrictions of position are posted conspicuously at the head of the patient’s bed and included in the nursing care plan (paper or electronic site).

A sufficient number of pillows are available to maintain body alignment.

Trochanter rolls and other positioning devices are useful.

If an arm is weak or paralyzed, the shoulder is positioned to approximate the joint space in the glenoid cavity. The affected arm should not be pulled. A pillow or small wedge in the axillary region helps prevent adduction of the shoulder.

Special resting hand splints may be ordered by the OT to prevent contracture. These should be removed periodically to assess the skin for pressure ulcers.

Edema of the extremities, particularly of the hands, is controlled by positioning and elevating the hand higher than the elbow.

An elastic glove may be ordered by the OT to control hand edema.

Prevention of footdrop is critical. Foot positioning devices, such as high-top sneakers or special splints, may be ordered by the PT.

Heels are kept off the bed to prevent pressure ulcers from developing. A pillow placed crosswise to elevate the lower legs or heel guards may be applied. (In many instances, the patient will already be wearing elastic stockings and air boots.)

The head should be supported in a neutral position through use of pillows or a soft collar or brace. This is especially important with patients with poor head control.

The upper extremities should also be supported with pillows. For patients with hemiplegia, the affected extremity should be positioned in a manner that the shoulder is supported with joint approximation to prevent subluxation.

Towel rolls can be utilized along the outer aspect of the thighs to keep the hips in neutral rotation.

The lower extremities should be supported under the knees and lower legs. Positioning a pillow under the lower legs elevates the heels off the bed to prevent pressure ulcers.

Passive: ROM is provided to a body joint by another person or outside force.

TABLE 11-2 EFFECTS OF IMMOBILIZATION ON THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

STRUCTURE

INITIAL CHANGES

ADVANCED CHANGES

Bones

Skeletal malalignment

Decreased bone mineral density

Skeletal deformities

Generalized osteoporosis

Fractures

Joints

Joint stiffness

Changes in periarticular and cartilaginous joint

Osteoarthritis structure

Fibrotic changes of ligaments and tendons

Shortening or stretching of ligaments

Decreased range of motion

Ankylosis

Contractures

Muscles

Decreased muscle mass

Decreased muscle strength

Muscle shortening

Muscle atrophy

Active: voluntary ROM to a body joint is independently executed by the individual.

Active assistive: ROM to a body joint is accomplished by the patient with the assistance of another person.

Active resistive: ROM is voluntarily provided to a body joint against resistance.

Isometric or muscle setting: exercises are accomplished by alternately tightening and relaxing the muscle without joint movement.

Choose a time when the patient is rested, comfortable, and pain free for optimal cooperation.

Explain the procedure, even if the patient is apparently unconscious.

Position in proper body alignment, and drape, as necessary, to avoid undue exposure. Drawing the curtains offers privacy and excludes environmental stimuli in the instance of an easily distracted patient.

Provide a comfortable room temperature to prevent chilling, shivering, and unwanted muscle contractions.

Maintain good posture to ensure efficient body movement; face the patient to observe facial reaction to the exercises.

Movements are slow, smooth, and rhythmical.

Move the body part to the point of resistance and stop.

Move the body part to the point of pain and stop.

If the patient becomes excessively fatigued, discontinue the exercises.

cord injury patient can make the difference between success and failure. The patient with hemiplegia is placed in the sitting position and instructed to support himself or herself with the unaffected arm and hand. The hand is placed flat on the bed slightly behind or at the side as a means of support. The affected arm and hand should also be placed in a weight-bearing position with or without the external support of the therapist or a brace such as an air splint. Weight bearing in the affected extremity can provide the sensory-motor feedback necessary to help normalize tone. Because there is a tendency to slouch to the affected side, the patient is reminded to sit straight and erect, focused on a balanced midline. Some conscious patients who have difficulty balancing while sitting in bed do well when they are helped to sit at the side of the bed or in a chair with their feet flat on the floor.

Two-person lift: physical transfer by at least two nursing staff members; no active patient participation

Mechanical lift: transfer using a lifting device that is operated by nursing staff members; no active patient participation

The patient, with assistance from one or more nursing staff members, stands and pivots on the unaffected leg; moderate patient participation is required. A transfer belt is worn around the patient’s waist to allow the nurse to grasp it to support the patient. Inspect the transfer belt to be sure it is not worn or defective.

With the assistance of a slide board, the patient is able to transfer from the bed to the chair with or without assistance. Sliding board transfers are typically for patients with lower extremity weight-bearing restrictions or inability to bear weight through the lower extremities as with patients with paraplegia or quadriplegia.

Independent transfer is the patient’s ability to transfer without assistance.

Independent: patient does not require any supervision or physical assistance to safely perform the activity.

Modified independent: patient does not require any supervision or physical assistance to safely perform the activity, but the task has been modified or increased time is given to complete the task. Use of an assistive device classifies a patient as modified independent.

Supervision or standby assistance: patient requires supervision, verbal cuing or setup of items required to complete the task.

Physical assistance is not required.

Contact guard assistance: patient is able to complete the task with an assistant close by with hands on the patient or transfer belt for protection if the patient should experience loss of balance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree