Donna D. Ignatavicius

Rehabilitation Concepts for Chronic and Disabling Health Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

10 Assess the ability of patients to use assistive/adaptive devices to promote functional ability.

11 Plan interventions to prevent skin breakdown for rehabilitation patients.

12 Differentiate retraining methods for a patient with a spastic versus flaccid bladder and bowel.

13 Explain the primary concerns for patients being discharged to home after rehabilitation.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

A chronic health problem is one that has existed for at least 3 months. A disabling health problem is any physical or mental health/behavioral health problem that can cause disability. This text focuses on physical health problems; mental health/behavioral health problems are discussed in textbooks on mental health/behavioral health nursing.

Patients with chronic and disabling health problems often participate in rehabilitation programs to prevent further disability, maintain functional ability, and restore as much function as possible. The rehabilitation nurse collaborates with the nursing and health care team and coordinates the patient’s interdisciplinary care.

Overview

Chronic and disabling illnesses are a major health problem in the United States, with almost half of the population having one or more chronic health problems. Complications of chronic disease account for the majority of all deaths, and associated medical costs account for over two thirds of the nation’s health care cost. The rate of chronic and disabling conditions is expected to increase as more “baby boomers” approach late adulthood. Some people with chronic and disabling problems are in inpatient settings like rehabilitation centers and skilled nursing facilities, whereas others are managed at home.

Stroke, coronary artery disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and arthritis are common chronic diseases that can result in varying degrees of disability. Most occur in people older than 65 years. Younger adults are also living longer with potentially disabling congenital or genetic disorders that, in the past, would have shortened life expectancy. These specific health problems are discussed throughout this text.

Chronic and disabling conditions are not always illnesses (e.g., heart disease); they may also result from accidents. Accidents are a leading cause of death among young and middle-aged adults. Increasing numbers of people survive accidents because of advances in medical technology and safety equipment such as motor vehicle air bags. As a result, they are often faced with chronic, disabling neurologic conditions, such as traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and spinal cord injuries (SCIs).

These health problems are also common among military survivors who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The most common complications of these wars are TBI and single or multiple limb amputations. These disabilities require months to years of follow-up health care after returning to the community. Because of people living longer with chronic and disabling health problems, the need for rehabilitation is on the rise.

A growing number of middle-aged and older adults have total joint replacements, most often hips and knees. Many of these patients need daily (5-day-a-week) rehabilitation in skilled or transitional care units, often within long-term care (LTC) settings such as nursing homes. Older adults generally do not want to be admitted to nursing homes. The nurse or case manager needs to explain that the nursing home stay will be short, ranging from 1 to 6 weeks depending on the patient.

Some facilities have dedicated units for patients having short-term rehabilitation. Others have devoted units to geriatric rehabilitation or ventilator weaning. Follow-up rehabilitation therapy three times a week can be continued at home or on an outpatient (ambulatory care) basis.

Concepts Related to Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is the continuous process of learning to live with and manage chronic and disabling conditions, often those resulting from trauma. The main outcome of rehabilitation is that the patient will return to the best possible physical, mental, social, vocational, and economic capacity. Rehabilitation is not limited to the return of function in post-traumatic situations. It also includes education and therapy for any chronic illness characterized by a change in a body system function or body structure. Rehabilitation programs related to respiratory, cardiac, and musculoskeletal health problems are common examples that do not involve trauma.

After the acute condition or injury has been stabilized in a hospital, the patient may be discharged to continue the healing process at home, generally under the follow-up care of a nonhospital health care provider (e.g., a family physician). The nurse provides home care preparation, health teaching, psychosocial preparation, and information about various health care resources to help the patient resume his or her usual roles in society.

Some health problems require the intermediate step of rehabilitation (“rehab”), which can occur in a number of settings. Rehabilitation starts in the acute care hospital (sometimes called acute rehabilitation) and continues after discharge from the hospital. The nurse coordinates care from acute care through community-based care to ensure successful rehabilitation.

For continuing rehabilitation services, the most common inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) are freestanding rehabilitation hospitals, rehabilitation or skilled units within hospitals (e.g., transitional care units [TCUs]), and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) to which the patient is typically admitted for 1 to 3 weeks.

Ambulatory care rehabilitation departments and home rehabilitation programs may be needed for continuing less-intensive services. Some agencies have specialized clinics focused on rehabilitation of patients with specific health problems, such as those that care for patients with strokes; amputations; and large, chronic, and/or non-healing wounds. After disabled patients become more confident and independent, they may choose to live at home or in a group home. Group homes are facilities in which patients live independently together with other disabled adults. Each patient or group of patients has a care provider, such as a personal care aide, to assist with ADLs and decisions requiring accurate judgments. The patients may or may not be employed. The purpose of these centers is to provide independent living arrangements outside an institution, especially for younger patients with TBI or SCI.

The Rehabilitation Team

Successful rehabilitation depends on the coordinated effort of a group of the patient, family, and health care professionals in planning, implementing, and evaluating patient-centered care. The focus of the rehabilitation team is to restore and maintain the patient’s function to the extent possible.

In addition to the patient, family, and/or significant others, members of the interdisciplinary health care team in the rehabilitation setting may include:

• Nurses and nursing assistants

• Physical therapists and assistants

• Occupational therapists and assistants

• Speech-language pathologists and assistants

• Rehabilitation assistants/restorative aides

• Recreational or activity therapists

• Cognitive therapists or neuropsychologists

Not all settings that offer rehabilitation services have all of these members on their team. Not all patients require the services of all health care team members.

A physician who specializes in rehabilitative medicine is called a physiatrist. Most inpatient rehabilitation settings employ physiatrists. A primary care physician may also oversee care for the patient’s medical problems.

Rehabilitation nurses in the inpatient setting coordinate the efforts of health care team members and therefore function as the patient’s case manager. Nurses also create a rehabilitation milieu, which includes (Pryor, 2010):

• Allowing time for patients to practice self-management skills

• Encouraging patients and providing emotional support

• Protecting patients from embarrassment (e.g., bowel training)

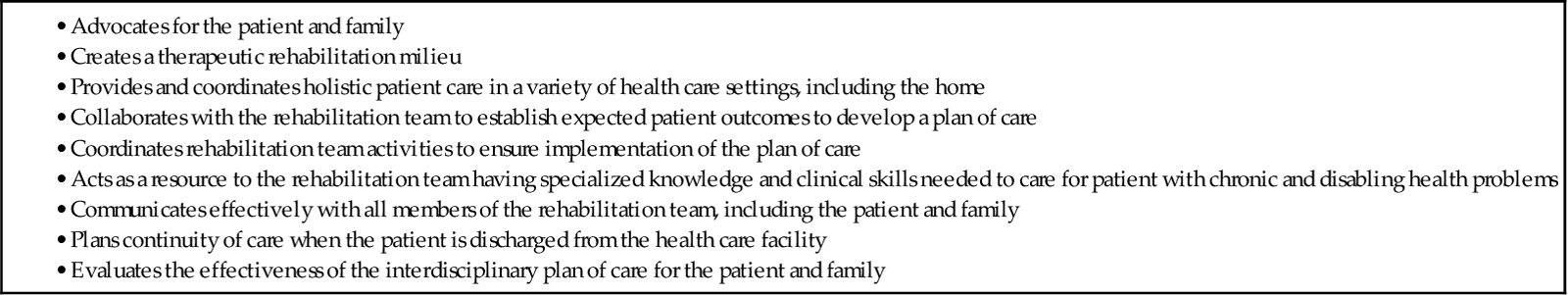

Table 8-1 summarizes the nurse’s role as part of the rehabilitation team. Because of an increase in the need for older adult rehabilitation, some nurses specialize in gerontologic rehabilitation (Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, 2008b). Nurses and other health care professionals may be designated as rehabilitation case managers in the home or in acute care settings. Case management is described in Chapter 1.

TABLE 8-1

NURSE’S ROLE IN THE REHABILITATION TEAM

Adapted from Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. (2008). Standards and scope of rehabilitation nursing practice, Glenview, IL: Author.

Physical therapists intervene to help the patient achieve self-management by focusing on gross mobility skills (e.g., by facilitating ambulation and teaching the patient to use a walker) (Fig. 8-1). They may also teach techniques for performing certain ADLs, such as transferring (e.g., moving into and out of bed), ambulating, and toileting, and can assist with cognitive retraining (often for patients with TBI). Physical therapy assistants (PTAs) may be employed to help the PT.

Occupational therapists work to develop the patient’s fine motor skills used for ADL self-management, such as those required for eating, hygiene, and dressing. OTs also teach patients how to perform independent living skills, such as cooking and shopping. Many inpatient rehabilitation facilities have fully furnished and equipped apartments where patients can practice independent living skills in a mock setting under supervision. To accomplish these outcomes, OTs teach skills related to coordination (e.g., hand movements) and cognitive retraining (Fig. 8-2). Occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) may be available to help the OT.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) evaluate and retrain patients with speech, language, or swallowing problems. Speech is the ability to say words, and language is the ability to understand and put words together in a meaningful way. Some patients, especially those who have experienced a head injury or stroke, have difficulty with both speech and language. Those who have had a stroke also may have dysphagia (difficulty with swallowing). SLPs provide screening and testing for dysphagia. If the patient has this problem, the SLP recommends appropriate foods and feeding techniques. Speech-language pathology assistants (SLPAs) may be employed to help the SLP.

PTs, OTs, and SLPs are collectively referred to as rehabilitation therapists. Assistants to PTs, OTs, and SLPs are called rehabilitation assistants. Restorative aides, usually in the nursing department, continue the rehabilitation therapy plan of care when therapists are not available. This model of care is common in long-term care settings, such as nursing homes.

Recreational or activity therapists work to help patients continue or develop hobbies or interests. These therapists often coordinate their efforts with those of the OT.

Cognitive therapists, usually neuropsychologists, work primarily with patients who have experienced head injuries with cognitive impairments. These therapists often use computers to assist with cognitive retraining.

Registered dietitians (RDs) may be needed to ensure that patients meet their nutritional needs. For example, for patients who need weight reduction, a restricted calorie diet can be planned. For patients who need additional calories or other nutrients, including vitamins, nutritionists can plan a patient-specific diet.

As their name implies, nursing assistants or nursing technicians assist in the care of patients. These members of the rehabilitation team are under the direct supervision of the registered nurse (RN) or licensed practical or vocational nurse (LPN or LVN).

Various counselors are helpful in promoting community reintegration of the patient and acceptance of the disability or chronic illness. Social workers help patients identify support services and resources, including financial assistance, and coordinate transfers to or discharges from the rehabilitation setting. Clinical psychologists also counsel patients and families on their psychological problems and on strategies to cope with disability. They may also perform a battery of cognitive assessments. Spiritual counselors, usually members of the clergy, specialize in spiritual assessments and care.

Vocational counselors assist with job placement, training, or further education. Work-related skills are taught if the patient needs to change careers because of the disability. If the patient has not yet completed high school, tutors may help with completion of the requirements for graduation.

Depending on the patient’s health care needs, additional team members may be included in the rehabilitation program, such as the geriatrician, respiratory therapist, pharmacist, and prosthetist. Interdisciplinary team conferences for planning care and evaluating the patient’s progress are held regularly with the patient, family members and significant others, and health care providers. The interdisciplinary patient record is shared and read by all team members.

Patient-centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Collect the history of the patient’s present condition, any current drug therapy, and any treatment programs in progress. Begin by obtaining general background data about the patient and family. This information includes cultural practices and the patient’s home situation. In collaboration with the occupational therapist, the nurse or case manager addresses the layout of the home. Together they discuss whether the physical layout at home, such as stairs or the width of doorways, will present a problem to the patient after discharge.

Assess the patient’s usual daily schedule and habits of everyday living. These include hygiene practices, eating, elimination, sexual activity, and sleep. Ask about the patient’s preferred method and time of bathing and hygiene activity. In assessing dietary patterns, note food likes and dislikes. Also, obtain information about bowel and bladder function and the normal pattern of elimination.

In assessing sexuality patterns, ask about changes in sexual function since the onset of the disability. The patient’s current and previous sleep habits, patterns, usual number of hours of sleep, and use of hypnotics are also assessed. Question whether the patient feels well rested after sleep. Sleep patterns have a significant impact on activity patterns. The assessment of activity patterns focuses on work, exercise, and recreational activities.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

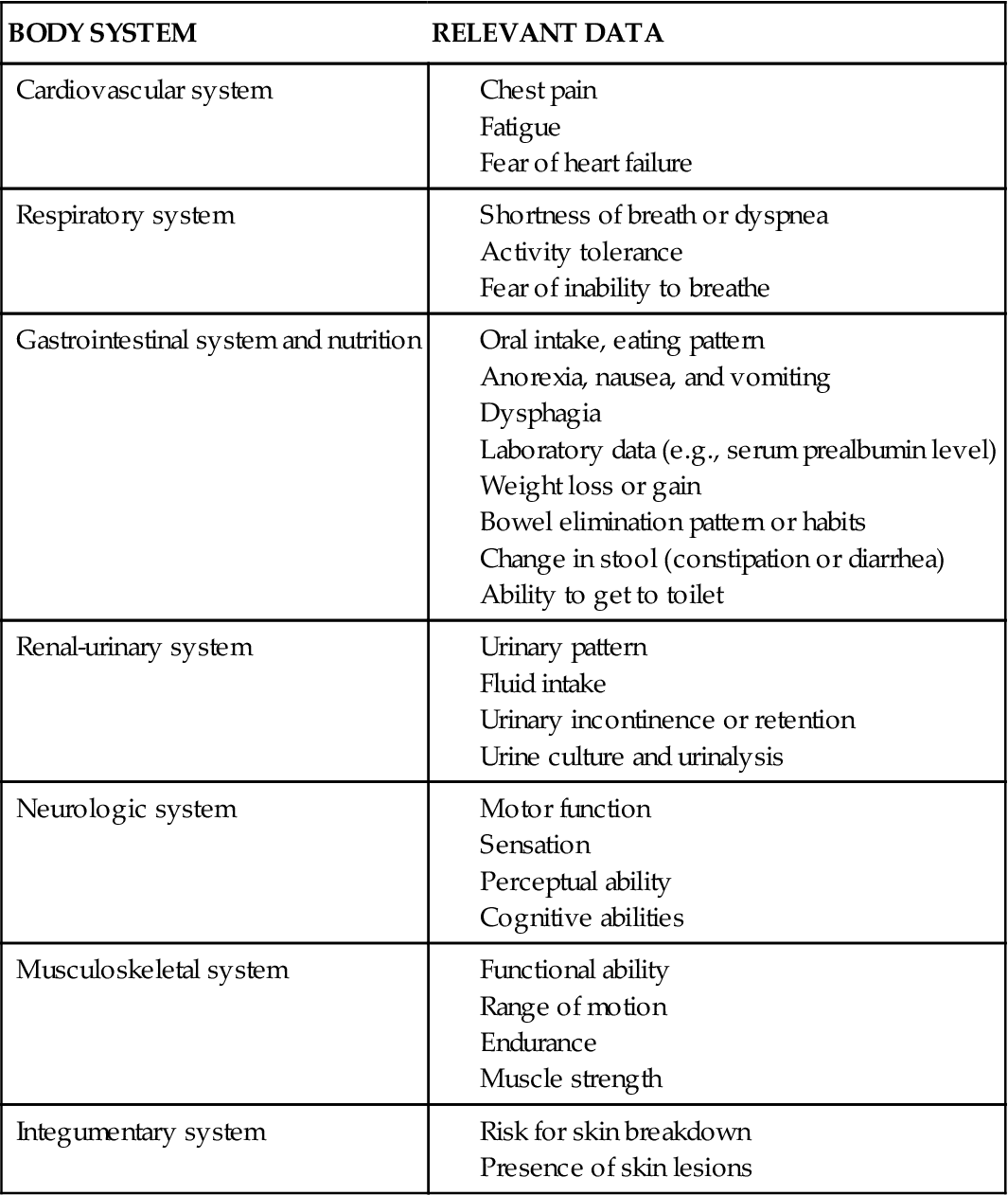

Upon admission for baseline and every day thereafter according agency policy and type of setting, collect the physical assessment data systematically according to major body systems (Table 8-2). The focus of the assessment related to rehabilitation and chronic disease is on the functional abilities of the patient.

TABLE 8-2

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENTS IN REHABILITATION SETTINGS

| BODY SYSTEM | RELEVANT DATA |

| Cardiovascular system | |

| Respiratory system | |

| Gastrointestinal system and nutrition | |

| Renal-urinary system | |

| Neurologic system | |

| Musculoskeletal system | |

| Integumentary system |

Cardiovascular and Respiratory Assessment.

An alteration in cardiac status may affect the patient’s cardiac output or cause activity intolerance. Assess associated signs and symptoms of decreased cardiac output (e.g., chest pain, fatigue). If present, determine when the patient experiences these symptoms and what relieves them. The physician may prescribe a change in drug therapy or may prescribe a prophylactic dose of nitroglycerin to be taken before the patient resumes activities. Collaborate with the physician and appropriate therapists to determine whether activities need to be modified.

For the patient showing fatigue, the nurse and patient plan methods for using limited energy resources. For instance, frequent rest periods can be taken throughout the day, especially before performing activities. Major tasks could be performed in the morning because most people have the most energy at that time.

A hindrance to rehabilitation for patients with cardiac disorders is fear, particularly for older adults. These patients may have survived a life-threatening experience (e.g., myocardial infarction) and may be so afraid of recurrence or death that they are unable or unwilling to resume any activity. They usually benefit from participation in a structured cardiac rehabilitation program. (See Chapter 40 for a complete description of cardiac rehabilitation.)

Ask the patient whether he or she has shortness of breath, chest pain, or severe weakness and fatigue during or after activity. Determine the level of activity that can be accomplished without these symptoms. For example, can the patient climb one flight of stairs without shortness of breath or does shortness of breath occur after climbing only two steps?

The fear associated with any inability to breathe normally can make a person dependent in many aspects of life. Some problems related to disorders of the respiratory system can be resolved or diminished, but some chronic diseases, such as emphysema, often continue to worsen.

Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Assessment.

Monitor the patient’s oral intake and pattern of eating. Also, assess for the presence of anorexia, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, or discomfort that may interfere with oral intake. Determine whether the patient wears dentures and, if so, whether they fit. Review the patient’s height, weight, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, serum prealbumin, and blood glucose levels (see Chapter 63 for discussion of how to perform a nutritional assessment). Weight loss or weight gain is particularly significant and may be related to an associated disease or to the illness that caused the disability.

Bowel elimination habits vary from person to person. They are often related to daily job or activity schedules, dietary patterns, age, and family or cultural background. Elimination habits may be difficult to assess, because many nurses are hesitant to request (and many patients are afraid to volunteer) information pertaining to elimination. Ask about usual bowel patterns before the injury or the illness.

Note any changes in the patient’s bowel routine or stool consistency. The most common problem for rehabilitation patients is constipation. In their classic best practice guidelines, the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (2002) defines constipation as the passage of hard, dry stool less than 3 times a week or significant change in the patient’s usual habits for more than 3 months. Examples of important changes include abdominal fullness and bloating and straining when having a bowel movement.

If the patient reports any alteration in elimination pattern, try to determine whether it is due to a change in diet, activity pattern, or medication use. Bowel habits are always evaluated based on what is normal for that person.

Ask whether the patient can manage bowel function independently. Independence in bowel elimination requires cognition, manual dexterity, sensation, muscle control, and mobility. If the patient requires help, determine whether someone is available at home to provide the assistance. Also assess the patient’s and family’s ability to cope with any dependency in bowel elimination.

Renal and Urinary Assessment.

Ask about the patient’s baseline urinary patterns, including the number of times he or she usually voids. Determine whether he or she routinely awakens during the night to empty the bladder (nocturia) or has uninterrupted sleep. Record fluid intake patterns and volume, including the type of fluids ingested and the time they were consumed.

Question whether the patient has ever had any problems with urinary incontinence or retention. Also, monitor laboratory reports, especially the results of the urinalysis and culture and sensitivity, if needed. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) among older adults are often missed because acute confusion may be the only indicator of the infection. Many heath care professionals expect older patients to be confused and may not detect this problem. If untreated, UTIs can lead to kidney infection and possible failure.

Neurologic and Musculoskeletal Assessment.

In rehabilitation, the neurologic assessment includes motor function, sensation, and cognition. Assess the patient’s pre-existing problems, general physical condition, and communication abilities. Patients may have dysphasia (slurred speech) because of facial muscle weakness or may have aphasia (inability to speak or comprehend), usually the result of a cerebral stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI). These communication problems are discussed in detail in the unit on problems of the nervous system.

Determine if the patient has paresis (weakness) or paralysis (absence of movement). Observe the patient’s gait. Identify sensory-perceptual changes, such as visual acuity, that could contribute to the patient’s risk for injury. Assess his or her response to light touch, hot or cold temperature, and position change in each extremity and on the trunk. Identify levels of decreased sensation. For a perceptual assessment, the nurse evaluates the patient’s ability to receive and understand what is heard and seen and the ability to express appropriate motor and verbal responses. During this portion of the assessment, begin to assess short-term and long-term memory.

Assess the patient’s cognitive abilities, especially if there is a head injury or stroke. Several tools are available to evaluate cognition. One of the most common is the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is described in detail in Chapter 44.

As with other body systems, nursing assessment of the musculoskeletal system focuses on function. Assess the patient’s musculoskeletal status, response to the impairment, and demands of the home, work, or school environment. Determine the patient’s endurance level, and measure active and passive joint range of motion (ROM). Review the results of manual muscle testing by physical therapy, which identifies the patient’s ROM and resistance against gravity. In this procedure, the therapist determines the degree of muscle strength present in each body segment.

Skin Assessment.

Identify actual or potential interruptions in skin integrity. To maintain healthy skin, the body must have adequate food, water, and oxygen intake; intact waste-removal mechanisms; sensation; and functional mobility. Changes in any of these variables can lead to rapid and extensive skin breakdown. If the patient cannot protect or maintain the skin, assess and plan for his or her needs.

Most rehabilitation settings use special skin assessment tools to identify patients at risk for skin breakdown. For example, the classic Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk (see Chapter 27) assesses several areas: sensory perception, skin moisture, activity level, nutritional status, and potential for friction and shear.

Other skin risk assessment tools are available. Some tools also include additional indicators of nutritional status, such as the serum prealbumin. When these levels are low, the patient is at high risk for pressure ulcers. Some tools include incontinence and altered mental state as risk factors.

If a pressure ulcer or other change in skin integrity develops, accurately assess the problem and its possible causes. Inspect the skin every 2 hours until the patient learns to inspect his or her own skin several times a day. Measure the depth and diameter of any open skin areas in inches or centimeters, depending on the policy of the facility. Assess the area around the open lesion to determine the presence of cellulitis or other tissue damage. Chapter 27 includes several widely used classification systems for assessing skin breakdown. Determine the patient’s knowledge about the cause and treatment of skin breakdown, as well as his or her ability to inspect the skin and participate in maintaining skin integrity.

In most health care agencies, a skin assessment and documentation tool (“skin sheet”) is used to keep track of each area of skin breakdown. A baseline assessment is conducted on admission to the agency, and the form is updated periodically depending on the agency’s policy and the nurse’s judgment. In most long-term care, acute care, and rehabilitation settings, and with the patient’s (or family’s if the patient cannot communicate) permission, photographs of the skin are taken on admission and at various intervals for documentation.