Introduction

The public expects midwifery practice to be of a competent standard and midwives have a high level of respect. Society has become better informed and expectations are rising. The midwife–client relationship is perhaps unique; it is based on trust and deals with our most valuable possession, health and the health of our baby. When the woman’s expectations are not met or when an error is made, this relationship is damaged. The result of this may be detrimental to health or even cause death. The cost to each person is therefore exceedingly high. The professional must then be closely examined and held accountable. Women need to feel that midwives have achieved an appropriate level of education and are professionally competent.

Self-regulation

Regulation of the midwifery profession was first defined in 1902 when the British government passed the Midwives Act. The need to prepare and educate midwives for their role had been finally endorsed by the government, which acknowledged the relationship between educated midwives and better outcomes for women and babies during childbirth. The title ‘midwife’ became protected by law and along with this established the principle that only trained practitioners (midwives or doctors) could attend women during childbirth. The professionalisation of midwives became established through a self-regulating approach, giving the profession wide-ranging powers and autonomy over its direction and protocols for care. This was essentially a contract between the state and the profession.

Subsequent amendments over a significant period of time led to the creation of the NMC by 2002. The NMC is an example of state-licensed self-regulation, i.e. the rules and principles established by institutions are given support from the state by legislation. This approach provides the NMC with a high degree of authority.

The structure of the council is set out under the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Statutory Instruments 2002/253). The NMC is currently composed of four statutory committees:

The IC, CCC and HC are concerned with fitness to practise allegations.

The Department of Health (DH 2007) published a report which sets out the government’s strategy for reforming and modernising the system of healthcare regulation. In line with the recommendations in the White Paper Trust, Assurance and Safety: the regulation of health professionals in the 21st century (DH 2007), the composition of the Council has changed to a smaller, more board-like structure to include lay persons and, most importantly, registrant members do not form a majority. The White Paper suggests that ‘the existence of professional majorities undermines councils’ independence and their perceived independence’ (1.10, p25). The NMC now has 12 lay and registrant members appointed by the Privy Council, including one member from each of the four UK countries.

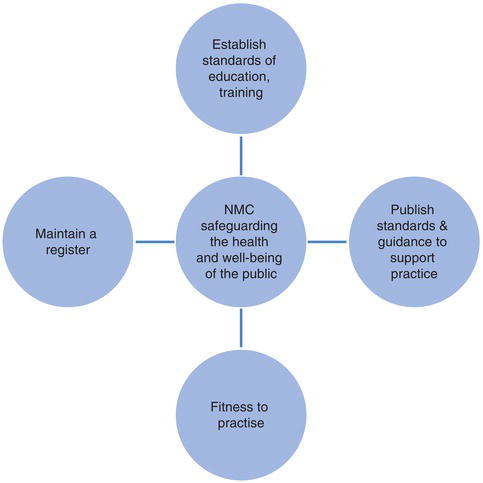

The core function of the NMC is to establish standards of education, training, conduct and performance for nursing and midwifery and to ensure those standards are maintained, thereby safeguarding the health and well-being of the public. These functions are fundamental in the key tasks of the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Statutory Instruments 2002/253), which include the following:

- Part III Registration, whose purpose is to maintain a register of nurses and midwives eligible to practise in the UK. It is therefore illegal to practise as a midwife or nurse in the UK without being on the register.

- Part IV Education and Training, whose responsibility is to establish standards of education and training for both pre-registration and post-registration nursing and midwifery in order to register and remain on the register. Part IV also includes the validation of courses in approved universities.

- Part V Fitness to Practise considers allegations against nurses and midwives.

- Part VIII Midwifery Committee establishes the rules for midwifery standards and provides guidance for local supervisors of midwives.

More than a century on from the Midwives Act 1902, protection of the public remains at the heart of self-regulation and the NMC. As did the previous regulatory authority the United Kingdom Central Council for Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors (1983–2002), the NMC has had to embrace the fundamental tenets of these two different professions yet has maintained the specialist and specific interests and concerns relating to midwifery practice through establishing the Midwifery Committee. This professionally appointed, yet statutorily required group leads and affirms the direction and implications of legislation for the midwifery profession, both collaboratively with and/or independently of the regulation proposed for nurses. Concurrently, the NMC addresses political debates which challenge the impacts and consequences of being a self-regulating organisation. This appraisal comes especially in light of past events (DH 2004, Kennedy 2001, Redfern 2001, Smith 2004) which have undermined the public’s confidence generally in a range of health professions’ ability to police their own practitioners. The core functions of the NMC can be found in Figure 13.1.

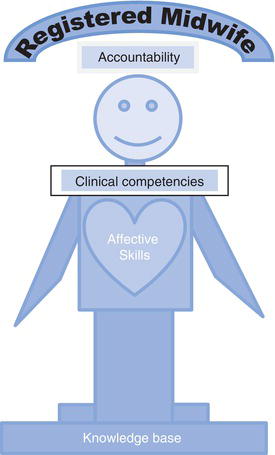

Figure 13.2 is a representation of how the NMC structures serve to regulate midwives. Understanding these will enable practitioners to utilise the boundaries set by the NMC to enable them to reach their full potential as midwives. Rules are not intended to restrict professionals but to empower them, so they can feel confident of their professional remit and sphere of practice. Midwives who feel empowered, in turn, empower women in their decision making and together they create a strong allegiance for achieving excellence in practice.

Standards and guidelines

In order to safeguard the health and well-being of the public, the NMC also publishes standards of practice and guidance. The fundamental standard of practice for both nurses and midwives is currently The Code: standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives (NMC 2008). In addition, midwives must practise in accordance with the NMC Midwives’ Rules (2012a). The Code aims to improve accountability and personal responsibility through a number of statements which reflect a wide set of principles, including ‘consent and confidentiality’, ‘working as a team’, ‘use the best available evidence’ and ‘record keeping’. The Code also encompasses principles relating to the way care is delivered, the basis for ethics – for example ‘act with integrity’. It further identifies a positive duty to respect equality and diversity.

Adhering to these standards allows nurses and midwives to use their professional judgement and to justify their actions. Nurses and midwives do have a professional duty to practise accordingly and if a nurse/midwife fails to adhere to the standards then this can be referred to a fitness to practise hearing.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council Midwives’ Rules

In addition to standard setting, under the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Statutory Instruments 2002/253), referred to as the Order, the NMC is also required to set the rules by which registered midwives must abide in addition to those relating to local supervising authorities and how they must discharge the function of supervision of midwives. The rules detail the requirements for midwives and their practice. The revised Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2012a) came into effect on 1st January 2013 and replace the previous rules. Under each rule, standards for the exercise by for the exercise by the local supervising authorities of their supervisory role provides further detail for the expected standard. With regard to the rules included under the section ‘Obligations and scope of practice’, guidance on the midwife standard is included which sets out the behaviour that would be reasonably expected of a midwife. For midwives, the Midwives’ Rules (NMC 2012a) and The Code (NMC 2008) are the fundamental ‘tools of the trade’; they are the tenets of daily practice and should be used by midwives to self-assess the quality of their practice and are also used to judge others’ practice standards.

The NMC has also produced guidance publications which provide further information in relation to the standards documents – for example, Standards for Medicines Management (NMC 2010) and Record Keeping (NMC 2009a). These publications provide nurses, midwives and students with a series of principles to support their practice. The standards and guidance are all available to view on the NMC website: www.nmc-uk.org/Publications.

The consequences of breaching The Code and the Midwives’ Rules may be serious for mothers, babies and midwives. The following section will focus on the role of the NMC and its fitness to practise procedures which deal with these breaches.

Fitness to practise

There are two legal documents that preside over the NMC fitness to practise (FtP) procedures. First, the Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 (Statutory Instruments 2002/253) (called the Order) Part V makes provisions for fitness to practise which establish and review the standards of conduct, performance and ethics expected of registrants. The Council’s function is to consider allegations which fall within article 22 (1) that may impair fitness to practise by reasons of misconduct, lack of competence, conviction or caution in the UK, ill health, entry on register has been fraudulently procured/incorrect or at the NMC’s own initiation. The second document is the Nursing and Midwifery (Fitness to Practise) Rules Order of Council 2004 SI2004/1761 (called the fitness to practise rules) and subsequent Nursing and Midwifery (Fitness to Practise) (Amendment) Rules Order of Council 2007, which provide the procedural rules for hearings. The NMC’s definition of fitness to practise is ‘suitability to be on the register without any restrictions’ (NMC 2011a).

The NMC has three statutory practice committees that deal with fitness to practise allegations:

Hearings and meetings are held before a panel of the relevant committee. IC hearings and meetings are held in private. CCC hearings are nearly always heard in public, demonstrating the NMC’s public accountability. However, this may depend upon the nature of the allegations, whether there is any public interest in dealing with them at a hearing and finally if it relates to the health of the registrant.

The White Paper Trust, Assurance and Safety: the regulation of health professionals in the 21st century (DH 2007 4.33, p66) states that ‘the independence and impartiality of those who pass judgement on health professions in fitness to practise proceedings is central and professional confidence in their findings and the sanctions that they impose’. With this in mind, the NMC can demonstrate its independent approach to fitness to practise proceedings as NMC Council members are not allowed to sit on any of the fitness to practise panels. In addition, practice panel members who are appointed to the IC are unable to sit on the CCC and vice versa.

Each IC, CCC and HC panel must include a minimum of three members, one of whom must be from the same health professional field and is registered on the same part of the NMC register as the person concerned. Therefore if the person concerned is a midwife and the allegation relates to midwifery practice, one of the panel members must be a midwife. The panel must also include at least one lay member. The panels have a chair who may be a registered or lay person. It is envisaged that having lay members appointed will give the public greater confidence in the outcomes of fitness to practise hearings. Legal assessors must also be present: they are not panel members involved in the decision making but are present to clarify and advise on the various points of law. CCC hearings are held in public, but HC hearings are held in private to maintain registrants’ confidentiality regarding their personal health matters.

The hearings are typically held at NMC offices throughout the UK. CCC hearings may be observed by the public and registrants. Encouraging midwives and student midwives to attend a hearing can give them a unique opportunity to further improve their understanding of the functions of the NMC fitness to practise procedures. The purpose of the visit is not to scare or promote anxiety but rather as a form of experiential learning.

Allegations are heard through adjudication at hearings or meetings. The NMC describes ‘adjudication’ as ‘the process of deciding whether an allegation is proved and, if so, what action or sanction to take’ (NMC 2011b). Ultimately hearings/meeting must have the public interest and protection of the public as their primary focus. In addition, the interests of the registrant must also be balanced into the equation. It is important that the panels strive to uphold proper standards of conduct and maintain public confidence in the profession, i.e. its reputation. They must also provide fairness between the parties.

The reader may assume that many nurses/midwives are referred to the NMC and that many of those referred are ultimately ‘struck off’. However, this is not the case. It is important to note that according to the NMC Annual Report 2011–2012 (NMC 2011c), there are over 671,000 nurses and midwives registered with the NMC in the UK and of those, approximately 0.6% are referred and less than 0.1% are given a sanction.

The NMC Annual Report 2011–2012 (NMC 2011c) identifies that the highest percentages of referrals were made by the employer, followed by a member of the public, service user or patient and then the police. The Report identifies the types of allegations relating to misconduct, including, amongst others, patient neglect, maladministration of drugs, record keeping, dishonesty, abuse of patients/ colleagues (physical, sexual, verbal, inappropriate relationship), pornography, racism and sleeping on duty. Allegations relating to lack of competence include, amongst others, patient care, lack of knowledge, skill and judgement. Examples of criminal allegations may include alcohol/drugs misuse, theft, child pornography and murder.