Introduction

Within this book, midwives are reminded of the importance of effective communication, interdisciplinary working and legislation in order to provide high-quality care. Chapter 18 on evidence-based practice further reinforces the importance of understanding research principles and methods. This helps to appraise the quality of reported studies and therefore to judge whether or not the conclusions of such studies should be taken into consideration in practice.

Decision making is closely linked to the appreciation of evidence. However, it needs to be seen in the context in which women, midwives and other healthcare professionals, as well as economists, politicians and ethicists, live, practise and relate to each other. The concept of decision making is extremely complex and brings to bear a multitude of aspects that can only be partly considered in this chapter.

The management and prioritising of competing demands through all aspects of midwifery practice will be given consideration. This will include decisions relating to referral to appropriate healthcare professionals when interventions to maintain the safety of the woman and her baby are required.

This chapter considers some fundamental principles of decision making as they complement or challenge evidence, experience or accepted practice. Two main areas are explored: clinical decision making and managerial decision making. Principles are then offered as guidance for midwives to follow in order to improve their judgement and decision-making skills.

Decision making

As individuals, we make a multitude of decisions every day. These decisions can be wide-ranging, from simple things like what time to get up in the morning, to major decisions on career choice, getting married, moving house or starting a family. The examples are endless, but essentially there are two main areas of decision making that midwives face in their day-to-day practice: clinical decision making and managerial decision making. Clinical decision making includes diagnostics and treatment. Examples of diagnostic choices in midwifery may be that a woman is or is not in labour or that a baby suffers or does not suffer from neonatal jaundice. Examples of treatment choices include the recommendation to use active management with Syntometrine or to apply physiological approach for the third stage of labour, or to use or not to use an epidural for a woman diagnosed with pregnancy-induced hypertension or pre-eclampsia.

The decisions or choices one makes are not necessarily always correct. Even though the majority of healthcare professionals aim to do the best they can for the people they care for, errors can occur with alarming frequency. This is highlighted in the publication of enquiries into maternal mortality (CMACE 2011a) and perinatal mortality (CMACE 2011b). Indeed, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CMACE 2011a) refers to ‘substandard’ care that could be classified as either ‘major’ or ‘minor’.

In this context, major substandard care is defined as care that contributed significantly to the death of the woman, i.e. different management would reasonably have been expected to alter the outcome. Minor substandard care is defined as a relevant contributory factor, in that different management might have made a difference although the woman’s survival was unlikely (CMACE 2011a). In most cases, the midwives and doctors caring for these women were doing their best, yet some of the women died. This demonstrates that even with the best of intentions, errors can and do occur. Fortunately, the majority of these errors do not lead to major problems, but occasionally they do.

Errors

Maternal death is the most negative outcome of pregnancy in midwifery and obstetric practice. Some maternal deaths are inevitable because of severe pathology. Examples are women with severe congenital heart malformation or cancer during pregnancy, but these events are rare. However, the majority of maternal deaths in the developed world are not associated with inevitable causes, they mostly result from human errors (CMACE 2011a). These errors can be broadly classified as:

- underdiagnosis: originates from a failure to recognise risk factors or a failure to appreciate the significance of presenting signs and symptoms; hence, the real pathology is not detected and action is not taken swiftly and correctly

- overdiagnosis: this is when a condition that does not exist is diagnosed, usually instead of the correct diagnosis, leading to inappropriate treatment and/or care management.

Clinical expertise is closely linked to clinical experience. Severe maternal pathology is by definition rare as pregnancy is usually a physiological state. Most midwives and obstetricians will never come across a maternal death or if they do, their experience will be very limited because this untoward event is very rare.

Therefore, it is easy to underestimate the severity of symptoms in a condition that most practitioners will not have encountered. This may go some way to explaining the poor interpretation of some of the presenting symptoms, and hence the delay in action, which lead to a catastrophic outcome. Evidence shows that more experienced practitioners, and those who are more certain of their diagnosis, are often right. However, some conditions are more difficult to diagnose. The misdiagnoses can at times be associated with ineffective or even harmful treatments (Ermenc 1999, McKelvie 1993; Roosen et al. 2000, Roulson et al. 2005, Sarode et al. 1993). An example of this is the administration of an anticoagulant to a person misdiagnosed as having a myocardial infarction, but who is in fact suffering from a gastric ulcer. The anticoagulant may lead to severe haemorrhage and subsequent death. It is easy to think that this is far-fetched and would not happen, but the literature clearly demonstrates that such errors are not uncommon (Cameron & McGoogan 1981). Sometimes an incorrect diagnosis is arrived at because practitioners rely too much on intuition and gut feeling instead of factual analysis of hard data.

Poor understanding and interpretation of statistics may lie at the root of many errors, leading to devastating consequences. This was clearly demonstrated in Sally Clark’s case by Professor Sir Roy Meadow, as his statistical interpretation of the likelihood of a second infant death from natural causes occurring in one family was flawed (Rozenberg 2006). Therefore, an understanding of some statistical terminology may help midwives question and interpret diagnostic tests more accurately. This may also help them to be better able to explain the significance of screening tests offered. For example, information on statistical values can be useful in supporting women and their partners to make informed decisions about screening for Down’s syndrome (also known as trisomy 21).

Moreover, midwives are regularly required to make decisions based on observations only. Questions may then be raised as to whether observations are diagnostic of a particular condition or not, as it is likely that the presentation of the information and its analysis are not always clearly identified. Sometimes, a positive test is taken as confirming the existence of a condition without analysing the likelihood of a false-positive test. Indeed, the steady rise in caesarean section is causing concern because this increase in maternal morbidity does not correlate with a corresponding fall in neonatal problems. When a baby has been delivered by emergency caesarean section he may cry loudly at birth; this should not be interpreted as fetal distress as this would be a misdiagnosis.

Using heuristics

The art of midwifery, like medicine, is the skilled application of medical science (Chapman & Sonnenberg 2003, Connolly et al. 2000), the processing of information (Lilford 1990) or the choice of decisions (Thornton 1990). However, as seen when examining the quality of judgement or diagnoses, common decisions can also appear quite complex when they are translated into a statistical model or framework, or if other factors are involved. The choice between active and physiological management of the third stage of labour provides a relatively simple example. If one considers only the lower risk of a postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), there is little doubt that the active management of the third stage of labour should be favoured. However, this is not without side-effects, in particular nausea, vomiting and hypertension. This information renders the choice more complex, particularly if the midwife or obstetrician is confronted with a situation of increased risk of PPH in a woman who has a phobia of vomiting or of injections.

Judgement or decision making often involves the manipulation of large amounts of information, yet evidence shows that the human brain can only manipulate small amounts at any one time. In order to simplify the process, one often uses rules of thumb or cognitive shortcuts, otherwise known as heuristics, to explain phenomena and come to decisions or solve problems (Bursztajn et al. 1990, Cioffi & Markham 1997). However, rules of thumb cannot be accurate, and heuristics fail systematically to process information that is necessary to make sense of the whole issue under consideration. It follows that any heuristic decision has a higher chance of being the result of only partial consideration of all the dimensions of a problem.

Human beings are extremely prone to these shortcomings. In midwifery, as in medical practice, decision making relies heavily on human judgement. Therefore, many mistakes are inevitable. The underdiagnosis of conditions such as thrombosis and/or thromboembolism, in pregnancy or in the postnatal period, offers a good example of the application of heuristics in maternity care where the severity of symptoms is not always recognised or the symptoms are attributed to other causes. Such cases have been highlighted by the Report on Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (RCOG 2004). The rarer an event, the less likely it is to be recognised by health professionals due to their lack of experience in putting all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together.

Clinical decision making

Diagnoses and clinical judgement are the subject of a multitude of errors. These errors sometimes arise because of poor understanding of statistical principles. The same can be said of clinical choices or decision making, and often for the same reasons: inadequate or inaccurate weighing of options and their consequences. When a systematic approach is used to make a choice, it is said to be subjected to decision analysis. This analytical framework originates mostly from psychology as psychologists have for some time been preoccupied with how and why people make mistakes. One such psychologist is Arthur Elstein and he defined decision analysis as:

a formal analytic framework that is increasingly being applied to the problem of selecting an action in clinical situations in which the optimal choice is not intuitively clear or the judgments of competent physicians differ. These situations often involve complex combinations of uncertainty, values, risks, and benefits, precisely where human judgment may encounter difficulty in reaching an optimal solution and where a decision aid may be useful.

(Elstein et al. 1986)

Some decisions are relatively easy to make, whilst others are more complex and difficult. As human beings, healthcare practitioners make mistakes. Fortunately, most of these lead to no significant consequences for their service users, but some do. In an effort to avoid errors, formal analytical models have been developed to guide good decisions. One of the best known is Bayes’ theorem. Bayes based his theorem on the fact that people hold basic beliefs about various phenomena, but these can be altered in the presence of new probabilistic information (Thompson 1999). Decision analysis combines probabilities of the potential outcomes such as:

- the prior probability of this outcome based on experience (Rayburn & Zhang 2002) or on epidemiological studies (Haynes de Regt et al. 1986, Spiegelhalter et al. 1999)

- the conditional probability of a positive test, a concept that is similar to the true positive rate or sensitivity of a test

- the posterior probability that combines the prior probability and the condition probability.

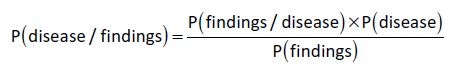

Bayes’ theorem expresses this as:

where:

P(disease/findings) = probability of a disease given a positive test, i.e. the posterior probability or odds

P(findings/disease) = probability of a positive test given the presence of the disease

P(disease) = probability of the disease, i.e. the prior probability or odds

P(findings) = probability of the findings.

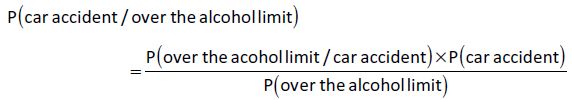

Bayes’ theorem provides an answer to the question: ‘What is the probability of a particular outcome given a particular action?’. For example, what are the chances of someone having a car accident given that they are over the alcohol limit?

The chance of a car driver having an accident if he is over the alcohol limit is not the same as the chance of the driver being over the limit given that he has had a car accident. In other words, the majority of people who are over the limit do not (fortunately for the innocent others) have car accidents but a sizeable proportion of people who have a car accident are over the alcohol limit. This explains why the police breathalyse all drivers involved in an accident or those who are driving erratically, but not all drivers who are driving apparently normally.

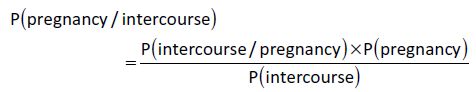

An example closer to midwifery is: ‘What are the chances of a woman becoming pregnant given that she has had sexual intercourse?’. Clearly, the majority of women who are pregnant have had sexual intercourse but the majority of women who have intercourse do not get pregnant every time.

These examples explain why we can only say that there is an increased chance or risk that one action will lead to a consequence, i.e. people who are over the alcohol limit are more likely to be involved in accidents and women who have sexual intercourse are more likely to get pregnant. However, statistically, one does not cause the other because if it did, that same action would always be followed by the same consequence. This is clearly not the case – increased risk, but not cause and effect.

Because of the elements that the Bayesian model takes on board, this process of decision making can sometimes be seen as too prescriptive. That is, if the Bayesian model is applied, the results should be accepted because the equation will have taken into consideration all the potential aspects of the problem. As the equation is used in the presence of uncertainty, and the model provides clarity, it would not make sense to dismiss the results because they do not quite match our feelings. It is presumed that the decision that combines the best chances and the best values for the outcome will be the decision of choice. This model of decision making would only be ideal if the level of information required in such a process was readily available to midwives and obstetricians, but in reality that is not necessarily so. Thompson (1999) suggests that there is a need for ‘middle ground’ where the intuitive-humanistic approach as a cognitive continuum should be taken into account in order to enhance the decision-making process.

Principles in clinical decision making

There is now evidence that using the internet search engine Google may help physicians identify diagnoses in some difficult cases (Tang & Ng 2006). One might be forgiven for thinking that it is a straightforward process to formulate a care management plan once the correct diagnosis is made. However, this is far from the truth. The cost-effectiveness of each treatment alternative and the increasing emphasis on service user empowerment and shared decision making have necessitated the need for ‘trade-offs’, thus rendering the decision-making process much more complex. Therefore, following a framework by applying some basic principles may help clinicians make better decisions. Bordley (2001) identifies the following principles:

- The problem must be correctly defined.

- Values, preferences and trade-offs must be clearly articulated.

- A wide range of creative solutions to the problem must be explored.

- Credible relevant data must be used for evaluating these alternatives.

- Logically correct reasoning must be used to evaluate alternatives.

- All the stakeholders need to be involved to ensure commitment to acting on the results of the analysis.

Most of the steps are relatively self-explanatory and are common sense. It is essential that a problem or a question should be framed correctly if it is to be answered efficiently in order to find the most suitable solution. It is equally important that all the potential answers ought to be stipulated so that they can be explored in turn. As seen when referring to Bayes’ theorem, it is vital that accurate data should be available not only on the likelihood of a condition, but also on the likelihood of treatment success or failure for each of the considered alternatives. All stakeholders must be involved in the decision-making process, including clinicians, health economists, policy makers, service providers and above all service users. The inclusion of service users and the exploration of their views will enable the identification of values, preferences and trade-offs during the decision-making process. The inclusion of values in the equation is called the maximising of utilities (O’Leary et al. 1995, Schackman et al. 2002).

The example of active management of the third stage of labour has already been identified as a potential clinical decision-making situation. To be able to make a decision about how best to manage this situation for a specific woman, information must be available, i.e. the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage generally, the specific risk assessment for this woman, bearing in mind her own specific risks, the alternatives available and the likelihood of outcomes given each alternative. Maximising utilities by adding the values that this woman would attach to each outcome would ultimately help to make the decision pertinent to this specific situation.

Other principles which may also come into play when making decisions are:

- clinicians’ (midwife/obstetrician) expertise

- policy or guidelines (national and local), e.g. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines

- legal frameworks such as legislation and Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) regulations

- research evidence

- available resources.

The clinician’s experience in decision making is of course central in the whole process. Her understanding of the various principles involved is vital in arriving at the appropriate decision. The adoption of clinical guidelines, rather than the more rigid protocols, enables midwives to include the values of the women they care for in the equation. In the example of the management of the third stage of labour, the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage can be gathered from epidemiological data and calculated according to the various decision options. The risk can then be more specifically calculated bearing in mind the specific risk factors of the woman. Finally, given that any choice will involve both potentially positive and negative outcomes, e.g. a reduced blood loss but an increased chance of nausea and vomiting (Prendeville et al. 2000), the midwife can now present the likelihood of the various outcomes with the given choices and then ask the woman to provide her own values on the outcomes. Including the woman’s values in the equation means that the final decision is tailor-made for the individual. It is essential to note that the likelihood of the outcome does not effect a change in the values of the woman.

Figure 16.1 illustrates these principles more clearly.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>