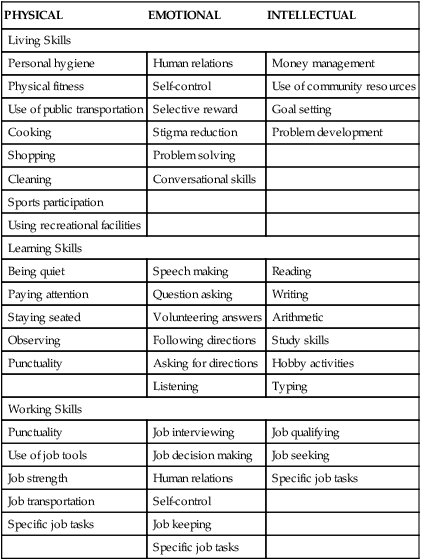

1. Define recovery and rehabilitation in psychiatric care. 2. Assess the nursing care needs of people in recovery and how families and communities respond to their needs. 3. Plan and implement recovery support of psychiatric nursing interventions with individuals, families, and communities. 4. Examine approaches to evaluate recovery support interventions related to individuals, families, and programs. Individuals who have serious mental illnesses, with the provision of appropriate and individualized supports, can recover from their illnesses and lead satisfying and productive lives. One of the eight Strategic Initiatives identified in the 2011–2014 plan of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is “Recovery Support” (SAMHSA, 2011). One-third of individuals with severe mental illnesses who receive community mental health services after lengthy stays in a state hospital fully recover, and another third improve significantly (SAMHSA, 2009). Recovery is a journey of healing and transformation enabling a person with a mental health problem to live a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential (USDHHS, 2006). The components of recovery are described in Box 14-1. Recovery is the process in which people are able to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities. For some individuals, recovery is the ability to live a fulfilling and productive life despite a disability. For others, recovery implies the reduction or complete remission of symptoms. Recovery also involves connectedness, or the capacity for mutual interpersonal relationships, and citizenship, which includes the rights, privileges, and responsibilities of membership in a democratic society (Ware et al, 2007, 2008). Self-determination is the foundation of person-centered and consumer-driven recovery supports and systems. The most important aspects of recovery are defined by each individual with the help of mental health care providers and the people who are most important in each person’s life. Having hope plays an essential role in an individual’s recovery (Stuart, 2010). It grew out of a need to create opportunities for people diagnosed with severe mental illness to live, learn, and work in their own communities. Psychiatric rehabilitation uses a person-centered, people-to-people approach that differs from the traditional medical model of care as seen in Table 14-1. TABLE 14-1 COMPARISON OF PSYCHIATRIC REHABILITATION AND TRADITIONAL MEDICAL MODELS OF CARE Some mental health care providers have concerns that the focus on recovery is not realistic. However as individuals participate in recovery-oriented programs and mental health professionals observe the progress that they make, these concerns are addressed and corrected (Delaney, 2010). For example, a recovery-oriented approach to providing nursing care to individuals who are taking psychiatric medication would take into account the fact that reluctance to take medication is often related to the person’s illness or refusal to acknowledge a need for medication. The recovery-oriented response is focused on learning about the patient’s reasons for not taking medication and then working with the patient to identify ways to make medication more acceptable based on the patient’s life goals (Roe and Swarbrick, 2007). There are a number of evidence-based practices that support and enhance recovery including: assertive community treatment, supported employment, illness management and recovery, integrated treatment for co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse, family psychoeducation, medication management, and permanent supported housing. All these practices except integrated treatment for co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse (see Chapter 23) and medication management (see Chapter 26) are addressed in this chapter. The exact causes of these characteristics have not been identified. Some could be related to primary and secondary symptoms or disabilities of the illness and others to society’s reaction to the person with mental illness (Pope, 2011). Attitudes that could contribute to this reaction are illustrated by the list of myths and facts about people with mental illness seen in Box 14-2. None of these myths is true, but they are commonly believed and stigmatize people with mental illness. They also can prevent people with mental illness from gaining access to needed services and opportunities. The nursing assessment of a patient with a serious mental illness should include an analysis of the physical, emotional, and intellectual components of the skills needed for living, learning, and working in the community. Table 14-2 presents skills required for successful functioning in the community. TABLE 14-2 POTENTIAL SKILLS NEEDED IN RECOVERY SUPPORT From Anthony WA: Principles of psychiatric rehabilitation, Baltimore, 1999, University Park Press. Families and other caregivers can be a major source of support for individuals who have serious mental illnesses. They can help by identifying potential problem areas and enhancing the patient’s adherence to the treatment plan. Caregivers should be educated about the patient’s condition and involved in the treatment process. Families should be viewed as resources, caregivers, and collaborators by psychiatric nurses (see Chapter 10). • Family structure, including developmental stage, roles, responsibilities, norms, and values • Family attitudes toward the mentally ill member • The emotional climate of the family (fearful, angry, depressed, anxious, calm) • The social supports available to the family, including extended family, friends, financial support, religious involvement, and community contacts • Past family experiences with mental health services • The family’s understanding of the patient’s problem and the plan of care

Recovery Support

Recovery

ASPECT OF CARE

PSYCHIATRIC REHABILITATION

TRADITIONAL MEDICAL REHABILITATION

Focus

Focus on wellness and health, not symptoms

Focus on disease, illness, and symptoms

Basis

Based on person’s abilities and functional behavior

Based on person’s disabilities and intrapsychic functioning

Setting

Caregiving in natural setting

Treatment in institutional settings

Relationship

Adult-to-adult relationship

Expert-to-patient relationship

Medication

Medicate as appropriate and tolerate some illness symptoms

Medicate until symptoms are controlled

Decision making

Case management in partnership with patient

Physician makes decisions and prescribes treatment

Emphasis

Emphasis on strengths, self-help, and interdependence

Emphasis on dependence and compliance

Assessment

The Individual

Behaviors Related to Serious Mental Illness

Living Skills Assessment

PHYSICAL

EMOTIONAL

INTELLECTUAL

Living Skills

Personal hygiene

Human relations

Money management

Physical fitness

Self-control

Use of community resources

Use of public transportation

Selective reward

Goal setting

Cooking

Stigma reduction

Problem development

Shopping

Problem solving

Cleaning

Conversational skills

Sports participation

Using recreational facilities

Learning Skills

Being quiet

Speech making

Reading

Paying attention

Question asking

Writing

Staying seated

Volunteering answers

Arithmetic

Observing

Following directions

Study skills

Punctuality

Asking for directions

Hobby activities

Listening

Typing

Working Skills

Punctuality

Job interviewing

Job qualifying

Use of job tools

Job decision making

Job seeking

Job strength

Human relations

Specific job tasks

Job transportation

Self-control

Specific job tasks

Job keeping

Specific job tasks

The Family

Components of Family Assessment.

Recovery Support

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access