Chapter 17

Quality and Safety

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

DEFINITIONS

There are many concepts and terms related to health care quality and safety. Definitions are:

Benchmarking is a tool to assist in quality-of-care decision making. Most recently, it has been defined as “an improvement process in which an organization measures its strategies, operations, or internal process performance against that of best-in-class organizations within or outside its industry, determines how those organizations achieved their performance levels, and uses that information to improve its own performance” (Sower et al., 2008, p. 4). Best-in-classis defined as “a standard that [an organization] should aspire to attain” (Sower et al., 2008, p. 5).

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) is defined by the American Society for Quality (ASQ) as “a philosophy and attitude for analyzing capabilities and processes and improving them repeatedly to achieve customer satisfaction” (ASQ, 2007). Further, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defined CQI as “techniques for measuring quality problems, designing interventions and their implementation, along with process re-measurements” (Shojania et al., 2004, p. 16). Evidence-based practice is defined by Sackett and colleagues (1996) as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (p. 71). More recently, evidence-based practices have been defined as “those clinical and administrative practices that have been proven to consistently produce specific, intended results” (Hyde et al., 2003, p. 15).

Health care quality indicators “provide an important tool for measuring the quality of care. Indicators are based on evidence of ‘best practices’ in health care that have been proven to lead to improvements in health status and thus can be used to assess, track, and monitor provider performance” (Hussey et al., 2007, p. i). A patient safety practice is “a type of process or structure whose application reduces the probability of adverse events resulting from exposure to the health care system across a range of conditions or procedures” (Shojania et al., 2001, p. 29).

A performance measure is “a quantitative tool (for example, rate, ratio, index, percentage) that provides an indication of an organization’s performance in relation to a specified process or outcome” (The Joint Commission, 2011a, ¶ 113). A performance measurement system is “an entity composed of a set of process and/or outcome measures of performance; processes for collecting, analyzing and disseminating these measures from multiple organizations; and an automated database that together can be used to facilitate performance improvement in health care organizations. A measurement system must be able to generate both internal comparisons of each participating organization’s performance over time, and external comparisons of performance among participating organizations” (The Joint Commission, 2011c, ¶ 1).

Quality refers to characteristics of and the pursuit of excellence. Health care quality is defined as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Lohr, 1990, pp. 128-129). Patient engagement is defined as “actions an individual must make to obtain the greatest benefit from the health care services available to them” (Center for Advancing Health, 2010, p. 2). A performance/quality improvement program is an overarching organizational strategy to ensure accountability of all employees, incorporating evidence-based health care quality indicators, to continuously improve care delivered to various populations. It is the organization’s blueprint for achieving and maintaining performance excellence.

Risk adjustment is a process in which differences among clients or variables such as age or disease severity are weighted or adjusted for in outcomes analyses or benchmarking efforts (Maas & Kerr, 1999). Enterprise risk management (ERM) is defined as “a structured analytical process that focuses on identifying and eliminating the financial impact and volatility of a portfolio of risks rather than on risk avoidance alone. Essential to this approach is an understanding that risk can be managed to gain competitive advantage” (Carroll, 2003, p. 1). An ERM program is defined as “an organization-wide program to identify risks, control occurrences, prevent damage, and control legal liability; it is a process whereby risks to the institution are evaluated and controlled.”

A sentinel event is “an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function. The phrase ‘or the risk thereof’ includes any process variation for which a recurrence would carry a significant chance of a serious adverse outcome. Such events are called ‘sentinel’ because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response” (The Joint Commission, 2012c, ¶ 2).

Standards are defined as written value statements. These statements form the rules that apply to key processes and the results that can be expected when the processes are performed according to specifications. The three basic types of standards for health care quality are (1) structure, (2) process, and (3) outcome standards (Katz & Green, 1997). Total quality management (TQM) is described as follows (ASQ, 2013): TQM is a term coined by the Naval Air Systems Command to describe its Japanese style management approach to quality improvement. “Since then, TQM has taken on many meanings. Simply put, it is a management approach to long-term success through customer satisfaction. TQM is based on all members of an organization participating in improving processes, products, services and the culture in which they work. The methods for implementing this approach are found in the teachings of such quality leaders as Philip B. Crosby, W. Edwards Deming, Armand V. Feigenbaum, Kaoru Ishikawa, and Joseph M. Juran”.

HEALTH CARE QUALITY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Professional nurses have an obligation to reasonably ensure that the care they provide is evidence-based and that work processes are consumer-centric. Providing “quality” health care is “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Lohr, 1990, pp. 128-129). Nurses, as leaders and managers, have served as health care quality professionals and have promoted standardization, measurement, and continuous quality improvement in a myriad of care delivery settings. Professional nurses have consistently held the practice of quality management in high regard and have the effective care of clients and families as their primary focus. Nurses are bound by their professional associatizon’s Code of Ethics (Fowler, 2008) and scope of professional standards to participate in the continuous improvement of the services they provide. Specifically, in provision 3, the “nurse promotes, advocates for and strives to protect the health, safety and rights of the patient” (Fowler, 2008, p. 143). Recent health reform legislation serves as a “call to action” for professional nurses—from frontline clinicians to executives—to be actively involved in health care transformation. This includes ensuring that patients and families receive safe and effective health care (Institute of Medicine, 2011, p. 22).

Donald M. Berwick, MD, co-author of the book Curing Health Care: New Strategies for Quality Improvement (Berwick et al., 1990), was an early pioneer in identifying how the concepts of TQM programs could apply to health care. In 1991, the National Demonstration Project on Quality Improvement in Health Care was conducted as a collaboration between members of the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Harvard Community Health Plan, the Juran Institute, the Hospital Corporation of America, and other health care organizations (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], 2004). The goal was to apply the methods and tools of industrial quality improvement in a variety of organizations to determine whether they could apply to a service industry. Berwick was a principal investigator for this project. As a result of this endeavor, the IHI was founded and became an early advocate for the concepts of process improvement and team problem solving in health care organizations. In 2010, Berwick was appointed by President Obama as administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. He served for 18 months and was responsible for introducing the “triple aim”: improving the patient care experience, improving population health, and reducing health costs (Berwick et al., 2008). His administration was also responsible for initiating major transformative changes under the new health reform legislation.

• Processes and systems are the problems, not people.

• Standardization of processes is key to managing work and people.

• Quality can be enhanced only in safe, non-punitive work cultures.

• Quality measurement and monitoring is everyone’s job.

• The impetus for quality monitoring is not primarily for accreditation or regulatory compliance, but rather as a planned part of an organization’s culture to continuously enhance and improve its services, based on continuous feedback from employees and customers.

• Consumers and stakeholders must be included in all phases of quality improvement planning.

• Consensus among all stakeholders must be gained to have an impact on quality and safety.

• Health policy should include a focus on continuous enhancement of quality and safety.

A framework for understanding health care improvement has been proposed by the IOM Committee on Quality of Health Care in America (Box 17-1). These six aims for health care quality improvement propose that health care systems ensure that care is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

COLLABORATION AND HEALTH CARE QUALITY AS PROFESSIONAL NURSING IMPERATIVES

Collaboration should be a goal of any interaction, regardless of the workplace or situation. Collaboration is an imperative set by the American Nurses Association (ANA). The ANA, in its release of a revised Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements (Fowler, 2008), proposed that “The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public in promoting community, national, and international efforts to meet health needs” (Provision 8, p. 143). Collaborative partnerships are part of this imperative and shape the way professional nurses act clinically and how they participate in performance and quality improvement efforts.

Collaboration is about relationships. Conflict is typically the result of an undeveloped or poor interpersonal relationship with a colleague. To overcome conflicts, it is necessary to strengthen, not shy away from, the relationship of the two opposing parties. The Pew Health Professions Commission (PHPC) talked about practicing relationship-centered care as one of 21 health profession competencies for the twenty-first century (O’Neil & PHPC, 1998, p. 23). Relationship-centered care in this context surely involves nurse and client/family interactions, but it also stresses the importance of collaborative interdisciplinary relationships. These 21 competencies are necessary ingredients for effective professional relationships and can become guideposts for successful professional working relationships within a continuous improvement framework.

The 21 competencies also include a professional nurse’s responsibility and accountability to health care quality. The specific statements related to health care quality include “Take responsibility for quality of care and health outcomes at all levels,” and “Contribute to continuous improvement of the health care system” (O’Neill & PHPC, 1998, pp. 29-43) (Box 17-2).

INDUSTRIAL MODELS OF QUALITY

Shewhart (Deming, 2000b) explored causes of variation in work processes. He quantified these variations, categorizing variables as common or special cause. His Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) model is probably the most frequently used in health care quality settings today, as follows (Figure 17-1):

• Plan (identify an issue and plan a process improvement)

• Do (map the current and proposed process, collect data, and analyze the results)

• Check (propose a solution and check the results of the new process)

Shewhart also provided the industrial community with statistical process control techniques that are used widely today. Deming (2000a, b) adopted his work and refined it.

Juran (1989) defined quality as “fitness for use.” Quality, in his work, was defined as freedom from defects plus value and continuously meeting customer expectations. His approach to quality centered around the use of interdisciplinary teams that used diagnostic tools to understand why industrial processes produce a product not fit for use. His framework included a three-pronged approach: quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement. Quality planning:

• Identify customers and target markets

• Discover hidden and unmet customer needs

• Translate these needs into product or service requirements: a means to meet their needs (new standards, specifications, etc.)

• Develop a service or product that exceeds customers’ needs

• Develop the processes that will provide the service, or create the product, in the most efficient way

• Transfer these designs to the organization and the operating forces to be carried out (Juran Institute, 2009, ¶ 1-2).

In addition to PDCA, Deming focused on statistical process control techniques and on continuous quality improvement through a culture of quality. He is credited as being influential in the success of Japanese industries. He proposed 14 points to help management staff understand and commit to quality. These points are listed in Box 17-3 (Deming, 2000a, b). These 14 points, although created just after World War II, have heavily influenced health care’s adoption of quality principles.

STANDARDS OF QUALITY

Health care quality standards and measures can be grouped in three categories: structure, process, and outcome. Donabedian (1980) developed the initial theoretical model that identified that quality can be measured using these three aspects. Donabedian’s (1980) framework of structure, process, and outcomes is the most widely referenced model of quality; professional nurses have used this model to develop performance and quality improvement programs and conduct evidence-based improvement studies and research. Standards essentially define quality, against which performance and outcomes are measured. Standards and measures are typically developed from benchmarking activities and reviews of best practices. Therefore the selection of standards and measures is a critical activity in the performance and quality improvement process. Actually, standards establish the baseline against which measurement and evaluation are conducted. Therefore it is critical to decide who determines standards and which standards are selected to define quality. Over the past 20 years, national groups have been formed to gain consensus on performance standards and measures. One such entity is the National Quality Forum (NQF), a not-for-profit, public-private membership organization created to develop and implement a national strategy for health care quality measurement and reporting.

Outcome Standards and Measures

• American Nurses Association National Database for Nursing Quality Indicators®

• Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Selection criteria can then be adopted and measures chosen for a specific intervention or program. A number of selection criteria guideline statements have been developed, including the performance measurement evaluation criteria from the National Quality Forum (National Quality Forum, 2011). The performance measurement attributes common to these entities’ guideline statements have been reported in the set of criteria proposed to be used for a national health care quality report (Institute of Medicine [IOM], Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery, 2001). Common performance measurement selection criteria are listed in Box 17-4 (Pelletier & Hoffman, 2002). The adoption of these performance measurement selection criteria is the first step in developing a comprehensive performance measurement system.

More recently, an international working group on health care quality indicators defined the following as selection criteria (The Commonwealth Fund, 2004), which are similar to those previously cited:

• Feasibility: indicators already being collected by one or more countries

• Scientific soundness: indicators that are valid and reliable; existing reviews of the scientific evidence and approval by a consensus process in one or more countries

• Interpretability: indicators that allowed a clear conclusion (a clear direction) for policy makers

• Actionability: measures of processes or outcomes that could be directly affected by the health care entity

• Importance: indicators reflective of important health conditions representing a major share of the burden of disease, health care costs, or policy-maker priorities.

EMERGING MODELS OF HEALTH CARE PERFORMANCE AND QUALITY ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Six Sigma

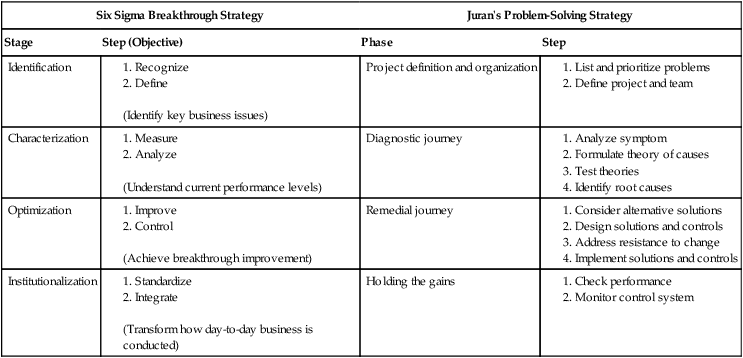

A strategy developed by Motorola and implemented successfully at General Electric (GE) and AlliedSignal Companies provided an innovative approach to reduce variation and error rates. Not surprisingly, the Six Sigma approach that these companies use is similar to tried-and-true approaches historically deployed by health care quality professionals, as previously described. In the Six Sigma breakthrough strategy, errors are measured in defects per million opportunities (dpmo). Six Sigma is achieved when the organization reaches an error or defect rate of 3.4 or less per one million. As a result of its implementation and investment of $6 million since 1995, GE boasted financial benefits of over $600 million in 1998 (Harry & Schroeder, 2000). AlliedSignal reported a 1.9% growth in operating margin in the first quarter, 1999, and “cumulative impact of Six Sigma has been a savings in excess of $2 billion in direct costs” (Harry & Schroeder, 2000, p. ix). The Six Sigma strategy (Harry & Schroeder, 2000) is remarkably similar to Juran’s problem-solving strategy (Plsek & Omnias, 1989), which has been applied to health care. Table 17-1 illustrates these similarities (Pelletier, 2000).

TABLE 17-1

Comparison of Six Sigma Breakthrough Strategy and Juran’s Problem-Solving Strategy

| Six Sigma Breakthrough Strategy | Juran’s Problem-Solving Strategy | ||

| Stage | Step (Objective) | Phase | Step |

| Identification | (Identify key business issues) | Project definition and organization | |

| Characterization | (Understand current performance levels) | Diagnostic journey | |

| Optimization | (Achieve breakthrough improvement) | Remedial journey | |

| Institutionalization | (Transform how day-to-day business is conducted) | Holding the gains | |

From Pelletier, L.R. (2000). On error-free health care: Mission possible! (Editorial). Journal for Healthcare Quality, 22(3), 9. Reprinted with permission from the National Association for Healthcare Quality.

Lean Enterprise

Lean Enterprise is a model of quality measurement that was originally associated with Deming but reintroduced to the United States by Womack in the mid-1990s (Jones & Womack, 2003). The premise of this model is that operational waste in an organization needs to be eliminated. Nightingale presents seven principles of lean thinking:

1. Adopt a holistic approach to enterprise transformation.

2. Identify relevant stakeholders and determine their value propositions.

3. Focus on enterprise effectiveness before efficiency.

4. Address internal and external enterprise interdependencies.

5. Ensure stability and flow within and across the enterprise.

6. Cultivate leadership to support and drive enterprise behaviors.

7. Emphasize organizational learning (Nightingale, 2009, p. 8).

Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award Program

The Baldrige National Quality Award (BNQA) establishes a set of performance standards that define a total quality organization. Named after the Secretary of Commerce, the BNQA “was established by Congress in 1987 to enhance the competitiveness and performance of U.S. businesses” (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2007, p. 1). The standards in seven areas of excellence are (1) leadership, (2) strategic planning, (3) customer and market focus (focus on patients, other customers, and markets), (4) information and analysis, (5) human resource focus, (6) process management, and (7) business results (organizational performance results). Organizations committed to quality improvement choose to adopt the BNQA approach as another means of defining and improving their organizational processes to achieve quality outcomes. Manufacturing, service, and small business were the original award categories, but in 1999, education and health care were added. With the trend in health care to adopt industry applications and measure sets for quality improvement, it was fitting that the health care industry was recognized as one that could benefit from participating in this program. It is appropriate for health care entities to strive to achieve internationally recognized standards for performance excellence, which enable them to benchmark their “best practices” with others in the field. The first health care organization to apply and be awarded the BNQA in health care was the SSM system in St. Louis in 2002. The Alliance for Performance Excellence is a network of national, state, and local Baldrige-based organizations helping organizations achieve performance excellence using the Baldrige criteria (www.baldrigepe.org/alliance/). Various states have also developed quality awards based on the BNQA criteria. Health care Baldrige award recipients have been found to have the advantage of displaying faster 5-year performance improvement (Foster & Chenoweth, 2011).

ISO 9000

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is a network of 163 countries that have agreed on an international reference for quality requirements in business and service industries. The ISO 9000 series of standards are those that address quality management—that is, what the organization does to manage its systems and processes. Health care sector standards, originally developed in 2001, were updated in 2005 (Frost, 2005). The achievement of an ISO 9000 registration results when a company complies with its own quality system. Benefits of ISO include the following (ISO, 2011):

• Make the development, manufacturing and supply of products and services more efficient, safer, and cleaner

• Facilitate trade between countries and make it fairer

• Provide governments with a technical base for health, safety, and environmental legislation, and conformity assessment

• Share technological advances and good management practice

• Safeguard consumers, and users in general, of products and services

• Make life simpler by providing solutions to common problems

High-Performance Organizations

As organizations continue to evolve their quality models, those that are in pursuit of continuous and ongoing improvement are embracing a concept referred to as high-performance organizations (HPOs). These are organizations that may already be practicing Six Sigma or Lean Enterprise or have achieved recognition through ISO 9000 registration or Malcolm Baldrige compliance. HPOs are those that have a culture of “building and sustaining a customer focused, team based organization that pays as much attention to results as it does to process” (Ward, 2004, p. 3). Following are some of the attributes of an HPO:

• Leaders who communicate a strong and clear mission and vision to employees

• Strategic thinking that anticipates customer needs and market changes

• A commitment to ongoing identification of problems and a preoccupation for potential failures

• Creative and improvisational problem solving to address failures or “near misses”

HPOs apply the principles learned through the study of high-reliability organizations (HROs). These are organizations that require reliability to ensure stable outcomes in the face of variable working conditions. In 2009, The Commonwealth Fund offered recommendations “for a comprehensive set of insurance, payment, and system reforms that could guarantee affordable coverage for all by 2012, improve health outcomes, and slow health spending growth by $3 trillion by 2020” (The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System, 2009, p. 3).

Magnet Designation

The American Nurses Credentialing Center’s (ANCC) Magnet Recognition Program® recognizes health care organizations for “quality patient care, nursing excellence and innovations in professional nursing practice” (ANCC, 2012, ¶ 1). The Magnet model includes the following components: Through a secondary analysis of a four-state survey of 26,276 nurses in 567 acute care hospitals, Kelly and colleagues (2011) recently found that Magnet designated hospitals “have better work environments, a more highly educated nursing workforce, superior nurse-to-patient staffing ratios, and higher nurse satisfaction than non-Magnet hospitals” (p. 428).

COSTS ASSOCIATED WITH POOR HEALTH CARE QUALITY

The cost associated with medical errors “in lost income, disability, and health care costs is as much as $29 billion annually” (Quality Interagency Coordination [QuIC] Task Force, 2000, p. 1) and plagues every sector in the health care industry. A more recent estimate of the cost of poor quality health care has escalated to $1.2 trillion annually of the $2.2 trillion spent annually on health care (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2008). The number of medical errors has been described as unacceptable by an IOM report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System (Kohn et al., 2000), which has been referenced widely in the professional and consumer press since its release. The IOM report has reached the highest levels in the federal government, but response to its findings and recommendations was lackluster at first. The research associated with this report was preceded by other federal initiatives. Poor quality includes overuse, underuse, misuse, waste, and inefficiency. Several reports on health care quality and safety have followed this landmark report.