Discuss the rationale for an emergent design in qualitative research and describe qualitative design features

Identify the major research traditions for qualitative research and describe the domain of inquiry of each

Identify the major research traditions for qualitative research and describe the domain of inquiry of each

Describe the main features and methods associated with ethnographic, phenomenologic, and grounded theory studies

Describe the main features and methods associated with ethnographic, phenomenologic, and grounded theory studies

Describe key features of historical research, case studies, narrative analysis, and descriptive qualitative studies

Describe key features of historical research, case studies, narrative analysis, and descriptive qualitative studies

Discuss the goals and features of research with an ideological perspective

Discuss the goals and features of research with an ideological perspective

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Basic social process (BSP)

Basic social process (BSP)

Bracketing

Bracketing

Case study

Case study

Constant comparison

Constant comparison

Constructivist grounded theory

Constructivist grounded theory

Core variable

Core variable

Critical ethnography

Critical ethnography

Critical theory

Critical theory

Descriptive phenomenology

Descriptive phenomenology

Descriptive qualitative study

Descriptive qualitative study

Emergent design

Emergent design

Ethnonursing research

Ethnonursing research

Feminist research

Feminist research

Grounded theory

Grounded theory

Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics

Historical research

Historical research

Interpretive phenomenology

Interpretive phenomenology

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis

Participant observation

Participant observation

Participatory action research (PAR)

Participatory action research (PAR)

Reflexive journal

Reflexive journal

THE DESIGN OF QUALITATIVE STUDIES

Quantitative researchers develop a research design before collecting their data and rarely depart from that design once the study is underway: They design and then they do. In qualitative research, by contrast, the study design often evolves during the project: Qualitative researchers design as they do. Qualitative studies use an emergent design that evolves as researchers make ongoing decisions about their data needs based on what they have already learned. An emergent design supports the researchers’ desire to have the inquiry reflect the realities and viewpoints of those under study—realities and viewpoints that are not known at the outset.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research Design

Qualitative inquiry has been guided by different disciplines with distinct methods and approaches. Some characteristics of qualitative research design are broadly applicable, however. In general, qualitative design

Is flexible, capable of adjusting to what is learned during data collection

Is flexible, capable of adjusting to what is learned during data collection

Often involves triangulating various data collection strategies

Often involves triangulating various data collection strategies

Tends to be holistic, striving for an understanding of the whole

Tends to be holistic, striving for an understanding of the whole

Requires researchers to become intensely involved and reflexive and can require a lot of time

Requires researchers to become intensely involved and reflexive and can require a lot of time

Benefits from ongoing data analysis to guide subsequent strategies

Benefits from ongoing data analysis to guide subsequent strategies

Although design decisions are not finalized beforehand, qualitative researchers typically do advance planning that supports their flexibility. For example, qualitative researchers make advance decisions with regard to their research tradition, the study site, a broad data collection strategy, and the equipment they will need in the field. Qualitative researchers plan for a variety of circumstances, but decisions about how to deal with them are resolved when the social context is better understood.

Qualitative Design Features

Some of the design features discussed in Chapter 9 apply to qualitative studies. To contrast quantitative and qualitative research design, we consider the elements identified in Table 9.1.

Intervention, Control, and Blinding

Qualitative research is almost always nonexperimental—although a qualitative substudy may be embedded in an experiment (see Chapter 13). Qualitative researchers do not conceptualize their studies as having independent and dependent variables and rarely control the people or environment under study. Blinding is rarely used by qualitative researchers. The goal is to develop a rich understanding of a phenomenon as it exists and as it is constructed by individuals within their own context.

Comparisons

Qualitative researchers typically do not plan to make group comparisons because the intent is to thoroughly describe or explain a phenomenon. Yet, patterns emerging in the data sometimes suggest illuminating comparisons. Indeed, as Morse (2004) noted in an editorial in Qualitative Health Research, “All description requires comparisons” (p. 1323). In analyzing qualitative data and in determining whether categories are saturated, there is a need to compare “this” to “that.”

Example of qualitative comparisons

Olsson and coresearchers (2015) studied patients’ decision making about undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation of severe aortic stenosis. They identified three distinct patterns of decision making in their sample of 24 patients, who were either ambivalent about the treatment, obedient and willing to let others decide, or reconciled and accepting of the treatment.

Research Settings

Qualitative researchers usually collect their data in naturalistic settings. And, whereas quantitative researchers usually strive to collect data in one type of setting to maintain constancy of conditions (e.g., conducting all interviews in participants’ homes), qualitative researchers may deliberately study phenomena in a various natural contexts, especially in ethnographic research.

Time Frames

Qualitative research, like quantitative research, can be either cross-sectional, with one data collection point, or longitudinal, with multiple data collection points designed to observe the evolution of a phenomenon.

Example of a longitudinal qualitative study

Hansen and colleagues (2015) studied the illness experiences of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma near the end of life. Data were collected through in-depth interviews once a month for up to 6 months from 14 patients.

Causality and Qualitative Research

In evidence hierarchies that rank evidence in terms of support of causal inferences (e.g., the one in Fig. 2.1), qualitative research is often near the base, which has led some to criticize evidence-based initiatives. The issue of causality, which has been controversial throughout the history of science, is especially contentious in qualitative research.

Some believe that causality is an inappropriate construct within the naturalistic paradigm. For example, Lincoln and Guba (1985) devoted an entire chapter of their book to a critique of causality and argued that it should be replaced with a concept that they called mutual shaping. According to their view, “Everything influences everything else, in the here and now” (p. 151).

Others, however, believe that qualitative methods are particularly well suited to understanding causal relationships. For example, Huberman and Miles (1994) argued that qualitative studies “can look directly and longitudinally at the local processes underlying a temporal series of events and states, showing how these led to specific outcomes, and ruling out rival hypotheses” (p. 434).

In attempting to not only describe but also explain phenomena, qualitative researchers who undertake in-depth studies will inevitably reveal patterns and processes suggesting causal interpretations. These interpretations can be (and often are) subjected to more systematic testing using more controlled methods of inquiry.

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TRADITIONS

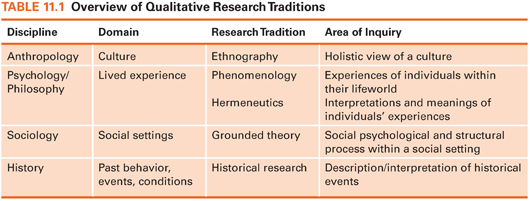

There is a wide variety of qualitative approaches. One classification system involves categorizing qualitative research according to disciplinary traditions. These traditions vary in their conceptualization of what types of questions are important to ask and in the methods considered appropriate for answering them. Table 11.1 provides an overview of several such traditions, some of which we introduced previously. This section describes traditions that have been prominent in nursing research.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves the description and interpretation of a culture and cultural behavior. Culture refers to the way a group of people live—the patterns of human activity and the values and norms that give activity significance. Ethnographies typically involve extensive fieldwork, which is the process by which the ethnographer comes to understand a culture. Because culture is, in itself, not visible or tangible, it must be inferred from the words, actions, and products of members of a group.

Ethnographic research sometimes concerns broadly defined cultures (e.g., the Maori culture of New Zealand) in what is sometimes called a macroethnography. However, ethnographers sometimes focus on more narrowly defined cultures in a focused ethnography. Focused ethnographies are studies of small units in a group or culture (e.g., the culture of an intensive care unit). An underlying assumption of the ethnographer is that every human group eventually evolves a culture that guides the members’ view of the world and the way they structure their experiences.

Example of a focused ethnography

Taylor and colleagues (2015) used a focused ethnographic approach to study nurses’ experiences of caring for older adults in the emergency department.

Ethnographers seek to learn from (rather than to study) members of a cultural group—to understand their worldview. Ethnographers distinguish “emic” and “etic” perspectives. An emic perspective refers to the way the members of the culture regard their world—the insiders’ view. The emic is the local concepts or means of expression used by members of the group under study to characterize their experiences. The etic perspective, by contrast, is the outsiders’ interpretation of the culture’s experiences—the words and concepts they use to refer to the same phenomena. Ethnographers strive to acquire an emic perspective of a culture and to reveal tacit knowledge—information about the culture that is so deeply embedded in cultural experiences that members do not talk about it or may not even be consciously aware of it.

Three broad types of information are usually sought by ethnographers: cultural behavior (what members of the culture do), cultural artifacts (what members make and use), and cultural speech (what they say). Ethnographers rely on a wide variety of data sources, including observations, in-depth interviews, records, and other types of physical evidence (e.g., photographs, diaries). Ethnographers typically use a strategy called participant observation in which they make observations of the culture under study while participating in its activities. Ethnographers also enlist the help of key informants to help them understand and interpret the events and activities being observed.

Ethnographic research is time-consuming—months and even years of fieldwork may be required to learn about a culture. Ethnography requires a certain level of intimacy with members of the cultural group, and such intimacy can be developed only over time and by working with those members as active participants.

The products of ethnographies are rich, holistic descriptions and interpretations of the culture under study. Among health care researchers, ethnography provides access to the health beliefs and health practices of a culture. Ethnographic inquiry can thus help to foster understanding of behaviors affecting health and illness. Leininger (1985) coined the phrase ethnonursing research, which she defined as “the study and analysis of the local or indigenous people’s viewpoints, beliefs, and practices about nursing care behavior and processes of designated cultures” (p. 38).

Example of an ethnonursing study

López Entrambasaguas and colleagues (2015) conducted an ethnonursing study to describe and understand cultural patterns related to HIV risk in Ayoreo women (indigenous Bolivians) who work in sex trades.

Ethnographers are often, but not always, “outsiders” to the culture under study. A type of ethnography that involves self-scrutiny (including scrutiny of groups or cultures to which researchers themselves belong) is called autoethnography or insider research. Autoethnography has several advantages, including ease of recruitment and the ability to get candid data based on preestablished trust. The drawback is that an “insider” may have biases about certain issues or may be so entrenched in the culture that valuable data get overlooked.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is an approach to understanding people’s everyday life experiences. Phenomenologic researchers ask: What is the essence of this phenomenon as experienced by these people, and what does it mean? Phenomenologists assume there is an essence—an essential structure—that can be understood, much as ethnographers assume that cultures exist. Essence is what makes a phenomenon what it is, and without which, it would not be what it is. Phenomenologists investigate subjective phenomena in the belief that critical truths about reality are grounded in people’s lived experiences. The topics appropriate to phenomenology are ones that are fundamental to the life experiences of humans, such as the meaning of suffering or the quality of life with chronic pain.

In phenomenologic studies, the main data source is in-depth conversations. Through these conversations, researchers strive to gain entrance into the informants’ world and to have access to their experiences as lived. Phenomenologic studies usually involve a small number of participants—often, 10 or fewer. For some phenomenologic researchers, the inquiry includes gathering not only information from informants but also efforts to experience the phenomenon, through participation, observation, and reflection. Phenomenologists share their insights in rich, vivid reports that describe key themes. The results section in a phenomenological report should help readers “see” something in a different way that enriches their understanding of experiences.

Phenomenology has several variants and interpretations. The two main schools of thought are descriptive phenomenology and interpretive phenomenology (hermeneutics).

Descriptive Phenomenology

Descriptive phenomenology was developed first by Husserl, who was primarily interested in the question, What do we know as persons? Descriptive phenomenologists insist on the careful portrayal of ordinary conscious experience of everyday life—a depiction of “things” as people experience them. These “things” include hearing, seeing, believing, feeling, remembering, deciding, and evaluating.

Descriptive phenomenologic studies often involve the following four steps: bracketing, intuiting, analyzing, and describing. Bracketing refers to the process of identifying and holding in abeyance preconceived beliefs and opinions about the phenomenon under study. Researchers strive to bracket out presuppositions in an effort to confront the data in pure form. Phenomenological researchers (as well as other qualitative researchers) often maintain a reflexive journal in their efforts to bracket.

Intuiting, the second step in descriptive phenomenology, occurs when researchers remain open to the meanings attributed to the phenomenon by those who have experienced it. Phenomenologic researchers then proceed to an analysis (i.e., extracting significant statements, categorizing, and making sense of essential meanings). Finally, the descriptive phase occurs when researchers come to understand and define the phenomenon.

Example of a descriptive phenomenological study

Meyer and coresearchers (2016) used a descriptive phenomenological approach in their study of spouses’ experiences of living with a partner affected with dementia.

Interpretive Phenomenology

Heidegger, a student of Husserl, is the founder of interpretive phenomenology or hermeneutics. Heidegger stressed interpreting and understanding—not just describing—human experience. He believed that lived experience is inherently an interpretive process and argued that hermeneutics (“understanding”) is a basic characteristic of human existence. (The term hermeneutics refers to the art and philosophy of interpreting the meaning of an object, such as a text or work of art.) The goals of interpretive phenomenological research are to enter another’s world and to discover the understandings found there.

Gadamer, another interpretive phenomenologist, described the interpretive process as a circular relationship—the hermeneutic circle—where one understands the whole of a text (e.g., an interview transcript) in terms of its parts and the parts in terms of the whole. Researchers continually question the meanings of the text.

Heidegger believed it is impossible to bracket one’s being-in-the-world, so bracketing does not occur in interpretive phenomenology. Hermeneutics presupposes prior understanding on the part of the researcher. Interpretive phenomenologists ideally approach each interview text with openness—they must be open to hearing what it is the text is saying.

Interpretive phenomenologists, like descriptive phenomenologists, rely primarily on in-depth interviews with individuals who have experienced the phenomenon of interest, but they may go beyond a traditional approach to gathering and analyzing data. For example, interpretive phenomenologists sometimes augment their understandings of the phenomenon through an analysis of supplementary texts, such as novels, poetry, or other artistic expressions—or they use such materials in their conversations with study participants.

Example of an interpretive phenomenological study

LaDonna and colleagues (2016) used an interpretive phenomenological approach in their exploration of the experience of caring for individuals with dysphagia and myotonic dystrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree