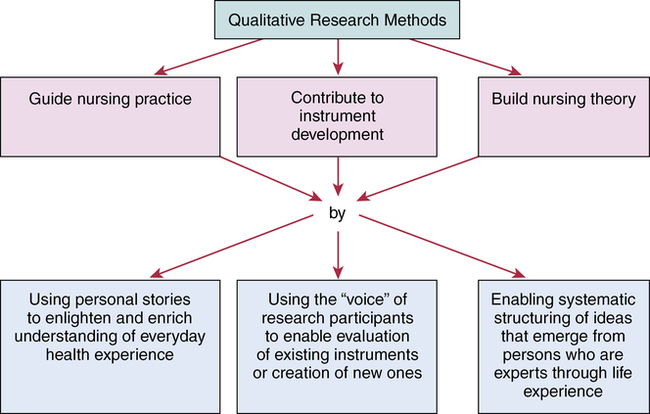

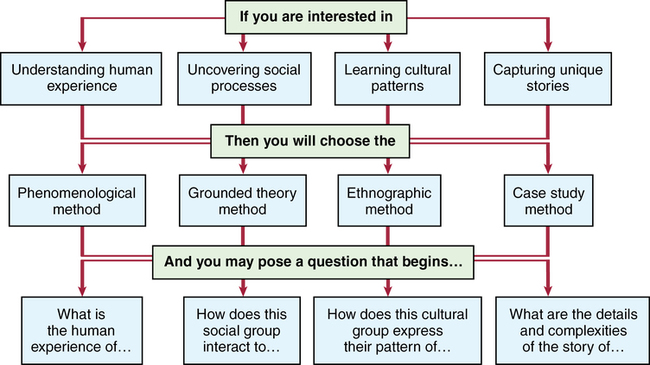

CHAPTER 6 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Identify the processes of phenomenological, grounded theory, ethnographic, and case study methods. • Recognize appropriate use of community-based participatory research methods. • Discuss significant issues that arise in conducting qualitative research in relation to such topics as ethics, criteria for judging scientific rigor, and combination of research methods. • Apply critiquing criteria to evaluate a report of qualitative research. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. Traditional hierarchies of research evaluation and how they categorize evidence from strongest to weakest, with emphasis on support for the effectiveness of interventions, is presented in Chapter 1. This perspective is limited, however, because it does not take into account the ways that qualitative research can support practice, as discussed in Chapter 5. There is no doubt about the merit of qualitative studies; the problem is that no one has developed a satisfactory method for including them in the evidence hierarchies. In addition, qualitative studies can answer the critical “why” questions that result from many evidence-based practice summaries; such summaries may report the answer to a research question, but they do not explain how it operates in the landscape of caring for people. • Personal and cultural constructions of disease, prevention, treatment, and risk • Living with disease and managing the physical, psychological, and social effects of multiple diseases and their treatment • Decision-making experiences with beginning and end-of-life, as well as assistive and life-extending, technological interventions • Contextual factors favoring and mitigating against quality care, health promotion, prevention of disease, and reduction of health disparities (Sandelowski, 2004; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007) The researcher using these methods believes that each unique human being attributes meaning to his or her experience and that experience evolves from his or her social and historical context. Thus, one person’s experience of pain is distinct from another’s and can be elucidated by the individual’s subjective description of it. For example, researchers interested in studying the lived experience of pain for the adolescent with rheumatoid arthritis will spend time in the adolescents’ natural settings, perhaps in their homes and schools (see Chapter 5). Research efforts will focus on uncovering the meaning of pain as it extends beyond the number of medications taken or a rating on a pain scale. Qualitative methods are grounded in the belief that objective data do not capture the whole of the human experience. Rather, the meaning of the adolescent’s pain emerges within the context of personal history, current relationships, and future plans as the adolescent lives daily life in dynamic interaction with the environment. Qualitative research is particularly well suited to study the human experience of health, a central concern of nursing science. Because qualitative methods focus on the whole of human experience and the meaning ascribed by individuals living the experience, these methods extend understanding of health beyond traditional measures of isolated concepts to include the complexity of the human health experience as it is occurring in everyday living. The evidence provided by qualitative studies that consider the unique perspectives, concerns, preferences, and expectations each patient brings to a clinical encounter offers in-depth understanding of human experience and the contexts in which they occur. Qualitative research, in addition to providing unique perspectives, has the ability to guide nursing practice, contribute to instrument development (see Chapter 15), and develop nursing theory (Figure 6-1). Thus far you have studied an overview of the qualitative research approach (see Chapter 5). Recognizing how the choice to use a qualitative approach reflects one’s worldview and the nature of some research questions, you have the necessary foundation for exploring selected qualitative methodologies. Now, as you review the Critical Thinking Decision Path and study the remainder of Chapter 6, note how different qualitative methods are appropriate for distinct areas of interest and also note how unique research questions might be studied with each method. In this chapter, we will explore several qualitative research methods in depth, including phenomenological, grounded theory, ethnographic, case study, and community-based participatory research methods. The phenomenological method is a process of learning and constructing the meaning of human experience through intensive dialogue with persons who are living the experience. It rests on the assumption that there is a structure and essence to shared experiences that can be narrated (Marshall & Rossman, 2011). The researcher’s goal is to understand the meaning of the experience as it is lived by the participant. Phenomenological studies usually incorporate data about the lived space, or spatiality; the lived body, or corporeality; lived time, or temporality; and lived human relations, or relationality. Meaning is pursued through a dialogic process, which extends beyond a simple interview and requires thoughtful presence on the part of the researcher. There are many schools of phenomenological research, and each school of thought uses slight differences in research methods. For example, Husserl belonged to the group of transcendental phenomenologists, who saw phenomenology as an interpretive, as opposed to an objective, mode of description. Using vivid and detailed attentiveness to description, researchers in this school explore the way knowledge comes into being. They seek to understand knowledge that is based on insights rather than objective characteristics (Richards & Morse, 2007). In contrast, Heidegger was an existential phenomenologist, who believed that the observer cannot separate him/herself from the lived world. Researchers in this school study how being in the world is a reality that is perceived; they study a reciprocal relationship between observers and the phenomenon of interest (Richards & Morse, 2007). In all forms of phenomenological research, you will find researchers asking a question about the lived experience and using methods that explore phenomena as they are embedded in people’s lives and environments. Because the focus of the phenomenological method is the lived experience, the researcher is likely to choose this method when studying some dimension of day-to-day existence for a particular group of people. See below for an example of this, in which Moules and colleagues’ (2012) study the lived experience of being a grandparent whose grandchild has cancer. The question that guides phenomenological research always asks about some human experience. It guides the researcher to ask the participant about some past or present experience. In most cases, the research question is not exactly the same as the question used to initiate dialogue with study participants. In fact, the research question and the interview questions are very similar; however, the difference is important. For example, Moules and colleagues (2012) state that the objective of their study was to understand, from the perspectives of the grandparents, the complexity and unique character of experiences of having a grandchild diagnosed, treated, and living with childhood cancer. Their ultimate goal was to guide the initiation of a network of support to the eldest of three generations of family members who are touched by cancer as they care for their own children (parents of the child with cancer) while loving, grieving, and worrying for their grandchildren (Moules et al., 2012). When using the phenomenological method, the researcher’s perspective is bracketed. This means that the researcher identifies their own personal biases about the phenomenon of interest to clarify how personal experience and beliefs may color what is heard and reported. Further, the phenomenological researcher is expected to set aside their personal biases—to bracket them—when engaged with the participants. By becoming aware of personal biases, the researcher is more likely to be able to pursue issues of importance as introduced by the participant, rather than leading the participant to issues the researcher deems important (Richards & Morse, 2007). Written or oral data may be collected when using the phenomenological method. The researcher may pose the query in writing and ask for a written response, or may schedule a time to interview the participant and record the interaction. In either case, the researcher may return to ask for clarification of written or recorded transcripts. To some extent, the particular data collection procedure is guided by the choice of a specific analysis technique. Different analysis techniques require different numbers of interviews. A concept known as “data saturation” usually guides decisions regarding how many interviews are enough. Data saturation is the situation of obtaining the full range of themes from the participants, so that in interviewing additional participants, no new data are emerging (Marshall & Rossman, 2011). Several techniques are available for data analysis when using the phenomenological method. Although the techniques are slightly different from each other, there is a general pattern of moving from the participant’s description to the researcher’s synthesis of all participants’ descriptions. Colaizzi (1978) suggests a series of seven steps: 1. Read the participants’ narratives to acquire a feeling for their ideas in order to understand them fully. 2. Extract significant statements to identify key words and sentences relating to the phenomenon under study. 3. Formulate meanings for each of these significant statements. 4. Repeat this process across participants’ stories and cluster recurrent meaningful themes. Validate these themes by returning to the informants to check interpretation. 5. Integrate the resulting themes into a rich description of the phenomenon under study. 6. Reduce these themes to an essential structure that offers an explanation of the behavior. 7. Return to the participants to conduct further interviews or elicit their opinions on the analysis in order to cross-check interpretation. Moules and colleagues (2012) do not cite a reference for data analysis; however, they do describe their methodology as having entered the hermeneutic circle as an engaged participant. They state that the hermeneutic circle is the generative recursion between the whole and part; an immersion into a dynamic and evolving interaction with the data both as a whole and in part through extensive readings and re-readings, reflection, dialogue, and by challenging assumptions, all of which help the researcher move toward an understanding that opens up new possibilities. When using the phenomenological method, the nurse researcher provides you with a path of information leading from the research question, through samples of participants’ words and the researcher’s interpretation, to the final synthesis that elaborates the lived experience as a narrative. When reading the report of a phenomenological study, the reader should find that detailed descriptive language is used to convey the complex meaning of the lived experience that offers the evidence for this qualitative method (Richards & Morse, 2007). Moules and colleagues (2012) listed the following as their interpretive findings: 1. Speed at which your life changes: The phone call that heralds a shaking of a universe 2. Out of sync, unfair, and trading places 4. Lives on hold while a view of the world changes: Holding one’s breath 5. The quest for normalcy: A new kind of normal 6. Helplessness: Nothing you can do 7. Criticism, blame, and guilt 9. The reemergence of sibling rivalry in adults The respondents also gave advice as grandparents to other grandparents: 1. Pay attention to the whole family. 3. Keep perspective and take care of yourself so that you do not become a burden. 4. Keep optimism and hope; be available and step in even at times when not invited. The grounded theory method is an inductive approach involving a systematic set of procedures to arrive at a theory about basic social processes (Silverman & Marvasti, 2008). The emergent theory is based on observations and perceptions of the social scene and evolves during data collection and analysis, as a product of the actual research process (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Grounded theory is widely used by social scientists today, largely because it describes a research approach to construct theory where no theory exists, or in situations where existing theory fails to provide evidence to explain a set of circumstances. Developed originally as a sociologist’s tool to investigate interactions in social settings (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), the grounded theory method is used in many disciplines; in fact, investigators from different disciplines use grounded theory to study the same phenomenon from their varying perspectives (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Denzin & Lincoln, 1998; Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Strauss & Corbin, 1994, 1997). For example, in an area of study such as chronic illness, a nurse might be interested in coping patterns within families, a psychologist might be interested in personal adjustment, and a sociologist might focus on group behavior in health care settings. Theories generated by each discipline will reflect the discipline and serve to help explain the phenomenon of interest within the discipline (Liehr & Marcus, 2002). In grounded theory, the usefulness of the study stems from the transferability of theories; that is, a theory derived from one study is applicable to another. Thus, the key objective of grounded theory is the development of formal theories spanning many disciplines that accurately reflect the cases from which they were derived (Sandelowski, 2004). Researchers typically use the grounded theory method when they are interested in social processes from the perspective of human interactions or patterns of action and interaction between and among various types of social units (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998). The basic social process is sometimes expressed in the form of a gerund (i.e., the -ing form of a verb when functioning as a noun), which is designed to indicate change occurring over time as social reality gets negotiated. For example, McCloskey (2012) describes the basic social process of women negotiating menopause as “changing focus.” Research questions appropriate for the grounded theory method are those that address basic social processes that shape human behavior. In a grounded theory study, the research question can be a statement or a broad question that permits in-depth explanation of the phenomenon. McCloskey’s (2012) study question was, “How do women move through the transition from menstrual to postmenstrual life?” In a grounded theory study, the researcher brings some knowledge of the literature to the study, but an exhaustive literature review may not be done. This allows theory to emerge directly from data and to reflect the contextual values that are integral to the social processes being studied. In this way, the new theory that emerges from the research is “grounded in” the data (Richards & Morse, 2007). Sample selection involves choosing participants who are experiencing the circumstance and selecting events and incidents related to the social process under investigation. (To read about a purposive sample, see Chapter 12.) McCloskey (2012) used community-based recruiting for her study; since perimenopausal women can be found in many places, she put notices in suburban and rural newspapers, a community center, a women’s shelter, and advertised by word of mouth. In the grounded theory method, you will find that data are collected through interviews and through skilled observations of individuals interacting in a social setting. Interviews are recorded and transcribed, and observations are recorded as field notes. Open-ended questions are used initially to identify concepts for further focus. At her first data collection point, McCloskey (2012) interviewed 15 women; this was followed by a focus group with the same women. Then, to revisit the study question, she reinterviewed 4 of the original 15 and added 4 new participants, for a study total of 19. She also collected data from journals in which the women reflected on and expanded their responses to the interview questions. A major feature of the grounded theory method is that data collection and analysis occur simultaneously. The process requires systematic data collection and documentation using field notes and transcribed interviews. Hunches about emerging patterns in the data are noted in memos that the researcher uses to direct activities in fieldwork. This technique, called theoretical sampling, is used to select experiences that will help the researcher to test hunches and ideas and to gather complete information about developing concepts. The researcher begins by noting indicators or actual events, actions, or words in the data. As data are concurrently collected and analyzed, new concepts, or abstractions, are developed from the indicators (Charmaz, 2000; Strauss, 1987). The initial analytical process is called open coding (Strauss, 1987). Data are examined carefully line by line, broken down into discrete parts, then compared for similarities and differences (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Coded data are continuously compared with new data as they are acquired during research. This is a process called the constant comparative method. When data collection is complete, codes in the data are clustered to form categories. The categories are expanded and developed or they are collapsed into one another, and relationships between the categories are used to develop new “grounded” theory. As a result, data collection, analysis, and theory generation have the direct, reciprocal relationship which grounds new theory in the perspectives of the research participants (Charmaz, 2000; Richards & Morse, 2007; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Qualitative approaches to research

Qualitative approach and nursing science

Qualitative research methods

Phenomenological method

Identifying the phenomenon

Structuring the study

Research question.

Researcher’s perspective.

Data gathering

Data analysis

Describing the findings

Grounded theory method

Identifying the phenomenon

Structuring the study

Research question.

Researcher’s perspective.

Sample selection.

Data gathering

Data analysis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree