Chapter 31. Q Methodology in Nursing Research

Carl Thompson and Rachel Baker

▪ Introduction

▪ Research questions suitable for Q methodological enquiry

▪ Q methodology – a walkthrough

▪ Strengths of Q methodology

▪ The limitations of Q methodology

▪ An example of a Q sort study

▪ Conclusion

▪ Resources

Glossary

Concourse

The universe of subjective viewpoints on a subject.

Q set

The set of items/statements, usually transcribed onto cards, which respondents are asked to sort according to the condition of instruction.

P set

Sample of persons selected (usually on theoretical grounds) to sort the Q sample.

Condition of instruction

All Q sorts are conducted according to some condition of instruction, i.e. direction to sort with reference to some specification such as sorting the cards representing your own point of view, from those ‘most like me’ to those ‘least like me’.

Q sort

The arrangement of items or statements by respondents according to the condition of instruction. Can be forced or unforced and administered by the researcher or self-administered.

Rotation

Rotation is a statistical technique in which the relation between Q sorts as they are represented in factor space can be examined from different angles.

Factors

Factors are analytic constructs calculated using correlations to reduce a large number of variables to a small number of underlying dimensions. In Q methodology each factor is seen as a distinct account relating to the topic studies, constructed from the correlations between individuals’ Q sorts.

Factor array

The composite Q sort representing a factor derived from the weighted averages of individual Q sorts.

Factor loadings

Factor loadings represent the degree of concordance between an individual Q sort and a factor.

Factor scores

Scores given to statements in the composite Q sort corresponding to the original values used in the Q sort (e.g. −5 to +5).

Research questions suitable for Q methodological enquiry

As with any research approach, the choice of method should be determined by the kinds of research questions that the methodology is designed to answer. Q is designed to answer research questions that focus on self-referent subjectivity – either individual or shared within groups. Self-referent subjectivity in this regard means communication of one’s point of view (Brown 1980). Subjectivity is present in such remarks as ‘it seems to me …’, or, ‘in my opinion …’. When such phrases accompany behaviour they usually indicate that someone has attempted to make sense of the meaning associated with personal experience and cognition. Q methodology has at its core the ability to access such frames of reference and to reveal their structures and forms. Q is used to study matters of taste, values and beliefs about which limited varieties of alternative stances are taken (Stainton Rogers 1995).

Examples of research questions and areas to which Q has been applied include:

▪ exploring economic rationality, health and lifestyle choices in people with diabetes (Baker 2003);

▪ the social construction of the meaning of ‘quality’ in the National Health Service (Thompson 1997);

▪ the meaning of health and illness (Stainton Rogers 1991);

▪ concepts of ‘accessibility and usefulness’ associated with research information sources (Thompson et al 2001);

▪ the social construction of barriers to research utilisation in health care (McCaughan et al 2002);

▪ lay perceptions of mental health (Herron 2000);

▪ the ethics of end-of-life decision making (Wong et al 2004);

▪ patients’ understanding of irritable bowel syndrome. (Stenner et al 2000).

In sum, Q methodology is most useful when the phenomenon under investigation (health beliefs, service quality, accessibility etc.) can be seen as socially constructed. According to this view:

People communicate to interpret events and to share those with others. For this reason it is believed that reality is constructed socially as a product of communication. Our meanings and understandings arise from our communication with others. How we understand objects and how we behave towards them depend in large measure on the social reality in force. (Littlejohn 1992, p. 190)

In seeking to understand the communication of beliefs on a phenomenon, Q methodologists reveal the structures of meaning surrounding a construct for the purposes of observation and study.

Q methodology – a walkthrough (See Box 31.1)

Selecting the Q set

The concourse is the starting point of every Q study. It comprises the set of views, opinions and beliefs (rather than facts) about a particular topic of concern. The Q set is a sample of items (usually statements but other items, such as pictures, can also be sorted) drawn from the concourse. The selection of statements to be sorted by respondents can be either unstructured or structured. In the former, items are chosen which are presumed to be of relevance to the study but where the emphasis is on representation. In the latter, sample items are chosen to represent points in a theoretical matrix. Here, the use of structured samples is akin to semi-structured schedules for interviews. The structure ensures specific dimensions of an argument or set of propositions are included. However, it is important to note that due to the immense number of possible permutations contained in a Q sort, the researcher is able to exert little influence over the factors that emerge. For example, a simple 10-item Q sort contains 1 209 600 (10 factorial) potentially unique sorts.

Box 31.1

The main stages of a Q method study

▪ Construction of a Q sample as a means of representing the possible characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. The Q sample contains stimuli that will trigger reflection on views and beliefs on the part of the respondent.

▪ Construction of a P (or person) sample. The P sample is made up of people most likely to inform understanding of the phenomenon being investigated (as with purposive sampling in qualitative enquiry) The respondent systematically rank orders the Q sample stimuli into a Q sort according to a condition of instruction, such as ‘sort the following according to those that most represent my views to those that least represent my views’.

▪ The first stage of analysis consists of transposing or ‘flipping’ the data set so that individuals (cases) become variables and variables (Q sorts) become the cases. Bivariate correlation coefficients of the N × N Q sorts are generated and then factor analysed. So similar Q sorts, not traits or Q sample items, are revealed. The association of each individual with the underlying factor (or perspective) is indicated by the factor loading.

▪ Scrutinising factor scores reveals the relative weighting for each of the Q sample items for each of the Q-sort-based perspectives. Each perspective has a factor array (or composite Q sort for all the people who define that factor) and also the statistically different items (i.e. those that make its perspective distinctive) can be examined through a series of pairwise comparisons.

▪ The final stage involves looking at where the perspectives converge and diverge and how this relates to extant theory and/or a priori assumptions or propositions.

Regardless of whether a structured or unstructured Q set is used it should, as far as possible, represent the ‘communication concourse’ of potential value sets. The number of items in the Q set varies between studies, but usually lies between 20 and 100 statements (Barbosa et al 1998).

Person sample (the P set)

In Q, individuals are selected purposefully according to their personal attributes depending on the research topic and not on the basis of statistical power. P set sizes vary between studies. ‘Intensive’ studies focus on small numbers of individuals who each undertake several Q sorts under different conditions of instruction. Brown (1996) described an example of such an intensive study in health research: a single respondent was asked to reflect on the quality of care received from his surgeon and to sort the Q set from, ‘most like the care given by my surgeon’ to ‘most unlike’. He was then asked to repeat the sort with respect to the care received from each of three nurses, the care provided by his mother during childhood illnesses and his care during another hospitalisation. The Q sorts produced by this individual were then subject to factor analysis to identify the factors associated with the different care experiences.

‘Extensive’ studies, in contrast, sample a larger P set in order to obtain Q sorts from a wide range of different people. The preferred size of the P set is related ultimately to the number of factors yielded and the way in which individual Q sorts ‘load’ on them and hence cannot be established firmly until data are collected. As a guide to the size of the P set, Brown (1996) suggested that 40–60 persons is more than likely adequate.

The power of purposive sampling lies in the ability to select information-rich cases and individuals likely to either strengthen or challenge emerging theory. The relationship between the individuals selected, the sampling frame used, and the type of generalisability is the same as in most qualitative techniques: i.e. the factors (points of view) that emerge provide the structure and form of shared views – rather than predicting the percentage of individuals subscribing to them in the population.

The Q sort

Data for factor analysis arise from individuals rank-ordering Q set items according to a ‘condition of instruction’ – a process known as Q sorting. Examples of typical conditions of instruction are:

Sort the items according to those with which you most agree (+5) to those with which you most disagree (−5).

Sort the items according to those that are most like object/person X (+5) to those most unlike that object/ person (−5)

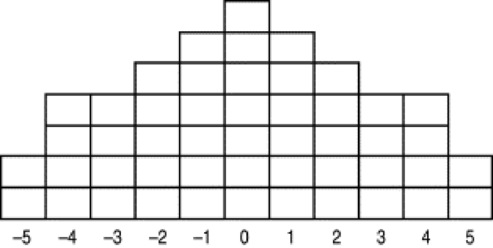

As a first basic sort and means of familiarisation, respondents are asked to place the cards in three roughly equal piles, for example ‘agree’, ‘disagree’, and ‘neutral’. The Q sort then follows, using a grid or scale marked, for example, from −5 to +5 and the number of cards permitted in each ‘pile’ or ‘column’ stated. An example of a sorting grid for a structured sort is shown in Figure 31.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|