Chapter 28. Focus Groups

Pauline Joyce

▪ Introduction

▪ Collecting data by focus groups

▪ An example of a focus group study

▪ Virtual focus groups

▪ Ethical considerations

▪ Benefits of focus groups

▪ Limitations of focus groups

▪ Conclusion

Introduction

In the previous chapter focus groups were defined.Another simple definition of focus group interviewing is: ‘a group of individuals selected and assembled by researchers to discuss and comment on, from personal experience, the topic that is the subject of the research’ (Powell & Single 1996, p. 499). The use of focus groups has grown in nursing (Webb & Kevern 2001). It is accepted that using ‘focus groups’ implies the researcher is actively encouraging of, and attentive to, group interaction (Kitzinger & Barbour 1999). The main advantage of focus groups is the opportunity to observe a large amount of interaction and discussion on a topic in a limited period of time. The person facilitating the focus group is called the moderator. Sometimes an assistant moderator is present to take notes and observe interactions.

Collecting data by focus groups

Focus group interviewing has been used as a sole method of data collection in some studies (Bulmer 1998, Hodges 2001 and Verpeet 2005) and as one of a number of qualitative data collection methods in others (McCutcheon & Pincombe 2001). Focus groups have also been employed in the initial phase of studies as a means of developing items for inclusion in later surveys (Sim 1996 and McLeod 2000), or to pursue poorly understood survey results, thus serving as a source of follow-up data to assist the primary method (Hodges 2001, McCutcheon 2001 and Morgan 1997).

The advantage of collecting data by focus group is the ability to observe group interaction on a topic. It provides evidence about similarities and differences in the participants’ opinions and experiences as opposed to the researcher reaching these conclusions from analyses of separate statements from individual interviews. Nonetheless, the individual interview has clear advantages over the focus group with regard to the amount of control that the researcher has and the greater amount of information that each participant has time to share. Box 28.1 and Box 28.2 provide some considerations (modified from Kreuger & Casey 2000) for when to use, and not to use, focus groups.

Box 28.1

When to use focus group interviews

Focus group interviews should be considered when:

▪ You are looking for a range of ideas or feelings that people have about something

▪ You are trying to understand differences in perspectives between groups or categories of people

▪ The purpose is to uncover factors that influence opinions, behaviour, or motivation, e.g. under what conditions should a health worker admit a mistake?

▪ You want ideas to emerge from the group

▪ You want to pilot test ideas, plans or policies

▪ The researcher needs information to design a large-scale quantitative study

▪ The researcher needs information to help shed light on quantitative data already collected

Box 28.2

When not to use focus group interviews

Focus group interviews should not be considered when:

▪ You are asking for sensitive information that should not be shared in a group or could be harmful to someone if it is shared in a group

▪ The environment is emotionally charged, and a group discussion is likely to intensify the conflict

▪ Other methodologies can produce better quality information

▪ You cannot ensure the confidentiality of sensitive information

Preparation for the focus group interview

The literature varies on the optimum size of a focus group. Generally, between four and eight participants are recommended. Fewer than four is not considered a focus group. It is difficult to predict accurately the precise number of participants. Interviewees can cancel for a variety of reasons as the date approaches. Morgan (1997) suggested over-recruiting by 20%. However, it has been highlighted that this figure should be closer to 50–100% for nurses (Macleod Clark et al 1996) because nurses may be difficult to recruit due to shift patterns and workload. The optimum size of the group may also reflect the characteristics of participants as well as the topic being discussed (Bloor et al 2001). Focus groups in Michell’s (1999) study on teenage lifestyles consisted typically of three or four pupils and were made up of friends and peers who were comfortable about attending the sessions together. However, this study used 76 one-to-one interviews and 21 focus groups. Larger groups can also present problems. Groups that are too large can become difficult to moderate and participants can feel frustrated if they have inadequate time to express their views or opinions. The more outgoing participants can dominate the interaction so that everyone present may not be contributing to the discussion. The number of participants can also have significant implications for recording and transcribing the group discussion.

Purposive sampling is frequently used for focus groups where the participants are recruited. Purposive sampling is based on the belief that a researcher’s knowledge about the population can be used to hand-pick the cases to be included in the sample (Polit & Hungler 1995). Random sampling is seldom used because of the small number of participants involved in focus groups. In addition, a randomly sampled group from the general population may be unlikely to hold a shared perspective on the research topic and may not be able to generate meaningful discussions (Jennings et al 2005). In terms of group composition it has been suggested that different hierarchical levels within a group should be avoided (Kreuger 2000 and Macleod Clark 1996). If a power differential exists, some participants may be reluctant to participate in the discussion (Mansell et al 2004). Another consideration is to decide whether to include people who are complete strangers or to access pre-existing groups (Barbour 2005).

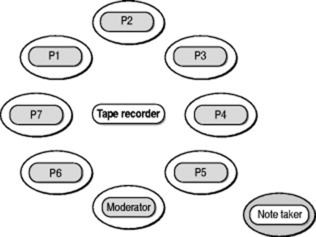

Once you have selected participants it is important to set locations, meeting dates and times that do not conflict with popular activities and functions. Select a location that is easy to travel to, safe, has refreshments and with adequate transportation and parking. The location will need to be free from visual or audible distractions. Comfortable chairs and a table should be available for writing notes and holding a microphone (Kreuger & Casey 2000). A round table may be better than a rectangular one so that moderators can be placed in a position equal to the participants (Fig. 28.1).

|

| Figure 28.1 Group layout. |

Contact with potential participants should be direct and personalised (Lane et al 2001). The first contact can be two weeks before the interview and usually takes the form of a letter (Fig. 28.2). It is a good idea to build a convincing case in your letter to include the benefits of carrying out this study and how the results will be used. When the participant agrees to take part in the focus group, follow up with a personalised letter, approximately one week before the session. This letter can provide additional details about the session, location and topic. It is worthwhile providing some refreshments prior to the interview. This time can act as a warm-up for participants to introduce themselves to each other and to the researcher. In seeking informed consent from participants to take part in the interview, the researcher should be clear that note-taking and recording facilities will be employed (Powell & Single 1996).

|

| Figure 28.2 Contact with participants. |

A focus group moderator has been defined as ‘a facilitator or discussion leader, not a discussion participant’ (Fern 2001, p. 73). Likewise Morgan (1997) suggested that the title ‘moderator’ reflects an orientation towards ‘helping out someone else’s discussion’ (p. 48). The underlying message from much of the literature on moderating focus groups is that the participants must feel comfortable with the moderator (McLeod et al 2000, Nyamanthi & Shuler 1990, Sim 1998 and McLeod 2000). The participants need to feel that the moderator has no vested interest in the outcome of the focus group. Equally, the most influential factor affecting the quality of the focus group is the moderator’s respect for the participants (Kreuger & Casey 2000) (Box 28.3). This includes the ability to listen and the self-discipline to withhold personal viewpoints. The moderator facilitates the discussion and, as such, is a background rather than a foreground figure. Too much control may do the study a disservice, but the moderator must apply skilful facilitation if there is over-domination of the group by particular participants. Likewise, the moderator must encourage contributions from the more reticent members of the group.

Box 28.3

Moderator skills

▪ Know key questions

▪ Respect

▪ Ability to listen

▪ Be aware of timing

Developing appropriate questions for a focus group is as important as for a one-to-one interview. Too many questions will not give the participants enough time to talk about each issue. One suggestion is to begin with questions that will generate discussions among the participants. Even though these opening questions are not the core of the researcher’s interest, they will help promote a lively interview (Morgan 1995). Pre-testing the interview guide can be undertaken through individual interviews, as these are easier and cheaper to organise than focus groups. However, Webb (2002) carried out a pilot focus group and made changes for subsequent focus groups.

Table 28.1 provides a preparation checklist for the focus group interview.

| Preparation checklist | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Determining the size of the group | 4–8 participants |

| Deciding on the number of groups | More than 1 if sole method |

| Selecting and recruiting participants | Purposive sampling |

| Set meeting dates, time, location | Any conflicting functions? |

| Personalise contacts | 3 contacts |

| Develop appropriate questions | Not too many |

Conducting the focus group interview

A pre-group self-completion questionnaire seeking demographic information may be used and participants should be asked to sign a consent form. These can be collected immediately before the group starts and can be a convenient time-filler in these awkward minutes waiting for people to arrive. Bloor et al (2001) suggested using the pre-group questionnaire to check for possible differences of viewpoints on the study topic within the group. Knowledge of these underlying issues can be advantageous to the researcher in interpreting the focus group data.

Flip charts and notes are used to collect data from the focus group but audio recording is now common. Equipment that is suitable for recording one-to-one interviews may not always produce a recording of sufficient quality when used with groups. Tape recorders with microphones which contain an automatic volume control should be avoided as they will adjust the volume to cope with a loud speaker so that you can miss some data from a quieter speaker who follows (Bloor et al 2001). Where an external microphone is used, it is important to check that both the cassette recorder and the microphone attachment are switched on. It is a good idea to start the group interview by asking members to identify themselves. This can serve a dual purpose. You can play back the recording and check audibility. The recording of names can also help the transcriber to identify the individual voices but this may have the disadvantage of making some participants self-conscious. You need to assure the participants of confidentiality and that you will use pseudonyms when presenting the data from the study.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access