CHAPTER 9 Public health in Australia

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Public health

Social determinants of health

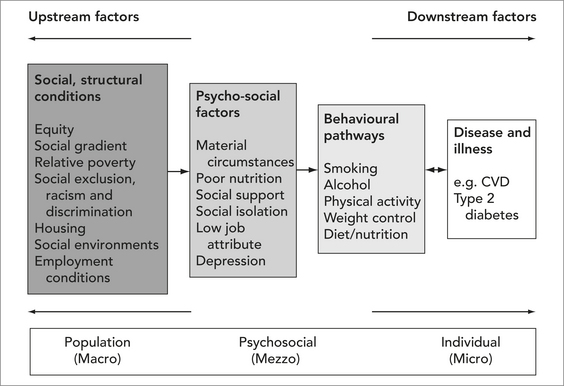

The social determinants of health are the social conditions in which people live and work, and they represent a significant shift in thinking about how to resolve issues of health inequity and disadvantage (Marmot 2006). Collectively, the social determinants of health are now recognised as the best predictors of health — the causal pathways both for individuals and populations. The evidence that has been systematically collected and analysed demonstrates how pathways through societal, political, environmental and economic determinants translate into illness and disease. The social conditions and settings in which people live their lives influence not just how people behave, but have a direct impact on the health of individuals, communities and populations. Some of these issues were raised in Chapter 2.

Population health and equity

A broader view of population health is that it describes both a level of analysis about risk exposure, the health outcomes of whole populations, or sub-populations, and the distribution of outcomes across those various populations (e.g. youth, children, refugees, older people) (Kindig 2007). Population health is increasingly concerned with studies and programs addressing health determinants (Berkman & Melchior 2006; Kindig 2007).

In theory, population health work should take account of the patterns of health determinants, and policies and interventions that link outcomes with determinants. But in reality, only a narrow range of determinants are considered in population health work by governments which focus on relationships between patterns of illness and disease in relation to socioeconomic factors and, to a lesser extent, racial and ethnic group differences. Good population health requires intersectoral approaches to programs and a focus on the needs of those with disadvantaged health status, aiming to reduce health and social inequities.

Typically, both public health and population health strategies are more ‘upstream’ than medical treatment services, which are classified primarily as ‘downstream’. Upstream strategies are focused on social and environmental change, and health-promoting policies and practices. Figure 9.1 illustrates downstream–upstream causal pathways towards the development of disease and illness.

Universal and targeted public health approaches

Other chapters (1, 2, 10, 11, 12, 13) discuss the higher incidence of poor health among socio-economically disadvantaged groups and problems of inequity. Public health places emphasis on high quality, universal programs such as immunisation, maternal and infant health, and cancer screening programs that are available to the whole population. As health inequities increase, a balance needs to be found for targeted programs that are tailored to meet specific needs of vulnerable populations and groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection