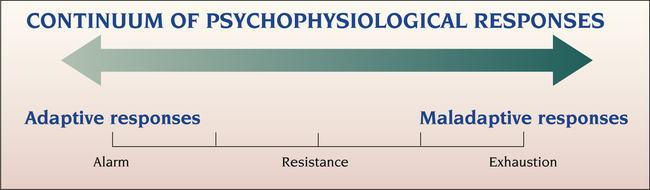

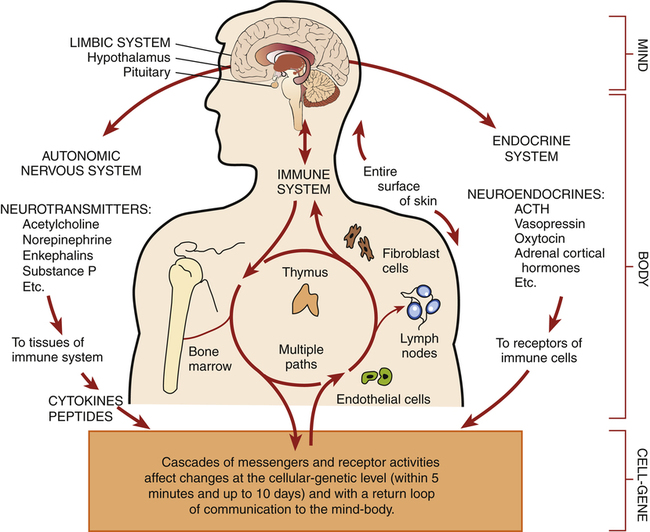

1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive psychophysiological responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with psychophysiological responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and appraisal of stressors related to psychophysiological responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to psychophysiological responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to psychophysiological responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to psychophysiological responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to psychophysiological responses. 8. Develop a patient education plan to teach adaptive strategies to cope with stress. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to psychophysiological responses. 10. Evaluate nursing care related to psychophysiological responses. 1. The alarm reaction. This reaction is the immediate response to a stressor in a localized area. Adrenocortical mechanisms respond, resulting in behaviors associated with the fight-or-flight response. 2. Stage of resistance. The body makes some effort to resist the stressor. The body adapts and functions at a less than optimal level. This requires a greater than usual expenditure of energy for survival. 3. Stage of exhaustion. The adaptive mechanisms become worn out and then fail. The negative effect of the stressor spreads to the entire organism. If the stressor is not removed or counteracted, death will result. Any experience that is perceived by the individual to be stressful may stimulate a psychophysiological response. The stress does not have to be recognized consciously, and often it is not. People who recognize that they are under stress are often unable to connect their cognitive understanding of stress with their physical symptoms of the psychophysiological disorder. Figure 16-1 illustrates the range of possible psychophysiological responses to stress, based on Selye’s theory. The primary behaviors observed with psychophysiological responses are the physical symptoms. These symptoms lead the person to seek health care. Psychological factors affecting the physical condition may involve any body part. The organ systems most commonly involved and the associated physical conditions are listed in Box 16-1. • Somatization disorder, in which the person has many physical complaints • Conversion disorder, in which a loss or alteration of physical functioning occurs • Hypochondriasis, the fear of illness or belief that one has an illness • Body dysmorphic disorder, in which a person with a normal appearance is concerned about having a physical defect • Pain disorder, in which psychological factors play an important role in the onset, severity, or maintenance of the pain Another type of somatoform disorder is conversion disorder, in which symptoms of some physical illnesses appear without any underlying organic cause (Tocchio, 2009). The organic symptom reduces the patient’s anxiety and usually gives a clue to the conflict. Conversion symptoms may include the following: • Sensory symptoms, such as numbness, blindness, or deafness • Motor symptoms, such as paralysis, tremors, or mutism • Visceral symptoms, such as urinary retention, headaches, or difficulty breathing It is often difficult to diagnose this reaction. Other patient behaviors may be helpful in making the diagnosis. Patients often display little anxiety or concern about the conversion symptom and its resulting disability. The classic term for this lack of concern is la belle indifference (Stone et al, 2006). The patient also tends to seek attention in ways not limited to the actual symptom. Pain is increasingly recognized as more than simply a sensory phenomenon. It is a complex sensory and emotional experience underlying potential disease. Pain is influenced by behavioral, cognitive, psychological, and motivational processes that require sophisticated assessments and multifaceted treatments for its control (American Nurse Today, 2011). Long-lasting pain has many effects and can produce changes in one’s mood, thought patterns, perceptions, coping abilities, and personality. Chronic pain combined with major depressive disorder results in higher medical service costs (Arnow et al, 2009). • Acute pain is a reflex biological response to injury. • Chronic pain is pain of at least 6 months’ duration. • Somatoform pain disorder is a preoccupation with pain in the absence of physical disease to account for its intensity. It does not follow a neuroanatomical distribution. A close correlation between stress or conflict and the initiation or exacerbation of the pain also may be a component of the disorder. All patients with chronic pain should be carefully evaluated for risk of suicide. Risk factors for understanding suicide in chronic pain patients include the following: the type, intensity, and duration of pain; sleep-onset insomnia co-occurring with pain; helplessness and hopelessness about pain; the desire to escape from pain; pain “catastrophizing” and avoidance; and problem-solving deficits (Tang and Crane, 2006). Normal sleep is defined as 6 to 9 hours of restorative sleep with characteristic sleep architecture and physiology and no complaints about quality of sleep, daytime sleepiness, or difficulties with mood, motivation, or performance during waking hours (Zunkel, 2005). Sleep disorders are common in the general population as well as among people with psychiatric disorders. About 80% of people with depression and 90% of patients with anxiety report experiencing problems sleeping (Kierlin, 2008). Sleep disturbance is common after traumatic events such as combat, trauma, or abuse. Sleep disruption also is reported by many patients in intensive care units. Nurses should remember that hospitals and other clinical settings are not conducive to restful sleep. Staff conversations, doors, pumps, pagers, monitors, and cleaning all can escalate noise levels. Sensitivity to noise and creating a quiet patient environment will directly help patients to sleep (King et al, 2007). The International Classification of Sleep Disorders identifies three major groupings (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2001): 1. The dyssomnias are the disorders that produce either difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or excessive sleepiness. They are divided into three groups of disorders: intrinsic sleep disorders, extrinsic sleep disorders, and circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Examples of dyssomnias include insomnia, narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, inadequate sleep hygiene, and alcohol/stimulant–dependent sleep disorder. 2. The parasomnias (i.e., the disorders of arousal, partial arousal, and sleep-stage transition) are disorders that intrude into the sleep process and are not primarily disorders of sleep and wake states per se. These disorders are signs of central nervous system activation, usually transmitted through skeletal muscle or autonomic nervous system channels. Examples of parasomnias include sleepwalking, sleep terrors, nightmares, sleep paralysis, sleep enuresis, primary snoring, and sudden infant death syndrome. 3. Sleep disorders associated with medical/psychiatric disorders include those conditions that are not primarily sleep disorders but are mental, neurological, or other medical disorders that have either sleep disturbance or excessive sleepiness as a major feature of the disorder. Approximately 35% to 58% of people in the United States report that they have difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or experience nonrestorative sleep (National Sleep Foundation, 2011). The majority of those affected are undiagnosed and untreated. In addition, millions of other people get inadequate sleep because of demanding work schedules, school, and other lifestyle issues. This group includes night-shift nurses, who report higher levels of fatigue and poorer sleep quality than day-shift nurses do. The assessment of patients with sleep problems is multifaceted, involving a detailed history and medical and psychiatric examinations, extensive questionnaires, the use of sleep diaries or logs, and often psychological testing (Buysse, 2005; Lee and Ward, 2005; Becker, 2008). Many patients are referred for formal sleep studies, which include all-night polysomnography and physiological measures of daytime sleepiness. Many members of the health care team collaborate within sleep centers to deliver multidisciplinary care. Perceived stress is in part heritable (Federenko et al, 2006). A biological tendency for particular psychophysiological responses may be inherited, underscoring the importance of genetic factors. For instance, epidemiological studies have shown that the lifetime prevalence for somatization disorder in the general population is 0.1% to 0.5% and is higher in women. However, among mothers and sisters of affected patients, the prevalence increases to 10% to 20%. The rate in monozygotic (identical) twins is 29%, and in dizygotic (fraternal) twins it is 10%. Therefore an inherited tendency for this disorder clearly exists.

Psychophysiological Responses and Somatoform and Sleep Disorders

Continuum of Psychophysiological Responses

Assessment

Behaviors

Physiological

Psychological

Pain

Sleep

Predisposing Factors

Biological

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Psychophysiological Responses and Somatoform and Sleep Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access