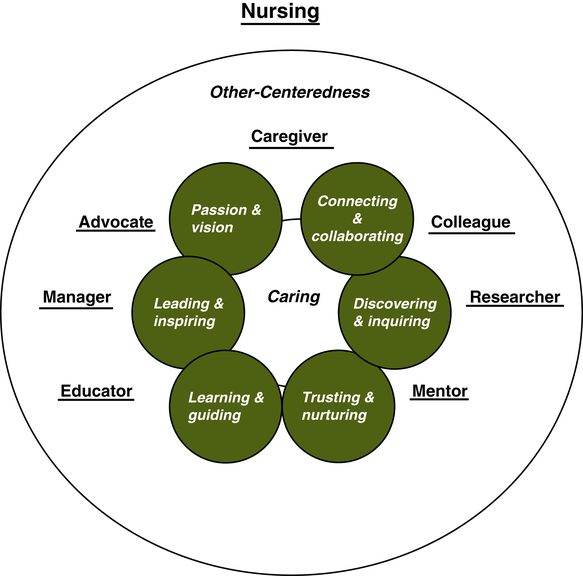

Sarah A. Delgado, RN, MSN, ACNP, Elke Jones Zschaebitz, MSN, FNP-BC and Elizabeth E. Friberg, DNP, RN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Articulate the impact of culture on perceptions of the professional nursing role. • Discuss the role and identity dyads in the framework of the nursing profession. • Describe the roles commonly assumed by professional nurses and the associated identity characteristics. • Discuss the impact of the multiple roles experienced by the professional nurse. • Differentiate between common sources of role stress and resultant role strain. To examine the professional nursing role, first consider the kaleidoscope of media and culture and their impact in shaping the way society sees nurses. This is vital during a time in which there is a shortage of nurses and an emerging dissonance between nursing education and the experiences of nurses in health care. Research shows that representations of professional roles and gender in media and the arts can shape a society’s view of that profession’s work. Dr. Stanley, a lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Curtin University of Technology in Perth, remarked, “Public perceptions of different professions are strongly influenced by the media, and in the past the way that nurses have been represented in featured films has often been at odds with the way nurses perceive their profession” (Stanley, 2008, para 3). Nurses have often been portrayed in film and television as comedic sex kittens—from B-movie productions in the 1970s such as Private Duty Nurses (Armitage, 1971) to Hot Lips Houlihan in the acclaimed television series M∗A∗S∗H∗ (Hornberger, 1972) to contemporary productions such as the television series ER (Burns, 1994), Scrubs (Lawrence, 2001), Nightingales (Cramer, 1988), and Grey’s Anatomy (Corn, 2005). In these portrayals, the nurse as caregiver is often twisted into an individual with uncontrolled libidinal impulse. Stanley (2008) noted, “Just over a quarter of the films I reviewed featured an overtly sexual representation of nurses … an image that has negative implications for nursing professionals” (para 9). In addition to sexualized roles, nurses have also been portrayed as harsh disciplinarians with an unyielding, even sadistic, worldview. Examples of these menacing roles include the ghoulish nurse in The Lost Weekend (Brackett & Wilder, 1945), the murderous caregiver in Stephen King’s Misery (Reiner, Scheinman, Stott, & Nicolaides, 1990), and most notably, the sinister and terrifying Nurse Ratched, who provoked emotional breakdowns in her emasculated, unstable, male patients in the Oscar-winning movie, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Douglas & Zaentz, 1975). As nursing is often seen as a female profession, these portrayals reflect society’s view of women, which shifted with the advent of the feminist movement, when women challenged sexist limitations on professional roles. Stanley believes, for instance, that the portrayal of nurses as sadistic coincided with the liberation of a repressed inner-self in line and the development of women’s power (Stanley, 2008). As women become more socially, professionally, and politically active, opportunities for women in the nursing field have also expanded. For example, military nurses are portrayed as heroes and heroines. The television show China Beach (Wells, 1988) was critiqued as “focusing on the women at the base, an emphasis fundamentally intended to undermine vainglorious heroism and to portray war instead, through women’s eyes, as a vast and elaborate conceit. Contemporary critics divided between those applauding the program’s feminine deflation of war, and those who regarded the characters and their orientations toward war as wholly stereotypical invocations of femininity” (Saenz, 1988, para 3). Recent films such as Pearl Harbor (Bruckheimer & Bay, 2001) and Ian McEwan’s 2007 film from the honored book Atonement (McEwan, 2001) portray war nurses as heroines and self-sacrificing women. In the Academy Award–winning film The English Patient (Zaentz & Minghella, 1996), the nurse Hanna’s selfless dedication to her craft and patient leads her to stay with him under desperate wartime conditions, her skilled compassion guiding her to assist him as he is dying. Although recent films and television show improvements in the portrayal of nurses, such as Hanna in The English Patient (Zaentz, 1996) or actress Julianna Margulies’ nursing role in ER (Spielberg, 1994), substantial obstacles and stereotypes still exist, driven by the gender-bound thinking attached to the nursing role. A major obstacle is demonstrated in the wildly successful film Meet the Parents (Tenenbaum, 2000), which reinforces how nursing struggles with its identity as gender-specific to women. Actor Ben Stiller’s character, Greg Focker, is a nurse who comically raises our consciousness of the negative perceptions of men in nursing. In one critical scene Greg is staying at his new girlfriend’s house in order to meet her father, Jack Byrnes, along with several other relatives, including two male physicians. When Greg arrives at the breakfast table—the only person in the house clad in pajamas—Jack introduces the bedraggled Greg to the group: Jack Byrnes: Greg’s a male nurse. Greg Focker: Yes, thank you, Jack. Kevin Rowley (surgeon): Wow, that’s great. I’d love to find time to do some volunteer work. Just the other day I saw a golden retriever, he had like a gimp, and you know I wish I could have done something. Greg Focker: Yeah, well I get paid too so it’s sort of an “everyone wins” thing. The stereotype that the male nurses are “less than male” and “do women’s work” is still an image reflected in contemporary U.S. culture despite a long history of men in nursing. In fact, as early as the fourth and fifth centuries, men worked as nurses (Evans, 2004). Today, one of the little-known facts of military nursing is the high percentage of men performing nursing roles in all three service branches. In the Army, 35.5% of its 3381 nurses are men; in the Air Force, 30% of 3790 nurses are men; and in the Navy, 36% of the 3125 nurses are men. By contrast, men make up only 6% of the nursing workforce in the United States (Lucas, 2009). Susan Wood, Associate Dean at the University of Washington School of Nursing, deplores the cultural bias against nurses and reflects the view of most nurses who see themselves played one-dimensionally with underlying stereotypes in culture when she writes, “I don’t think that movies accurately portray nurse as they really are … I don’t think there’s anything in film that portrays the scope of what a nurse does” (Rasmussen, 2001, para 6). Right or wrong, public perceptions of nursing roles point to the importance of a comprehensive analysis of role identity in nursing. Distinct from the stereotypes portrayed in the media, including film and television, the actual roles nurses play are uniquely multifaceted. The scope of these roles to which Susan Woods refers is a provocative one that incites many opinions within and external to the profession since Florence Nightingale first examined the role of nursing in her publication Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not (1860). The wisdom and vision of Nightingale were clear as she refrained from pigeonholing the profession in the context of time and space: “I do not pretend to teach her how, I ask her to teach herself, and for this purpose I venture to give her some hints” (Nightingale, 1860, p. 8). Role is defined by the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary as “a socially expected behavior pattern usually determined by an individual’s status in a particular society” (2009). The word role may be interpreted as a set of behaviors and expectations, rights and obligations, as conceptualized by actors in a situation guided by individuals with social position who set these behaviors. Roles are associated with social positions (status, power) and are shaped by the expectations of others in an individual’s workplace or social network (Biddle, 1979). Although structure and function are essential to an understanding of role, to define nursing in the context of expected behaviors would then interpret actions as solely prescribed by rules outlined in policy and procedure or a job description. From this functional perspective, the meaning of role is shallow and lacking the underpinnings of the individual’s professional identity, which underscores the motivation for selecting the profession. Identity is defined as “the distinguishing character or personality of an individual,” and the word identification is defined as “a psychological orientation of the self in regard to something (as a person or group) with the resulting feeling of close emotional association” (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, 2009). There is no set identity in nursing, as the profession consists of individuals with unique values and experiences. Nursing roles are guided by a derived identity and sense of self gathered from the organizations or work groups to which nurses belong (Hogg & Terry, 2000). From this perspective, identity can be understood as how a person sees himself or herself in a particular role; what a person believes about the world, moral choices, and social justice; and a person’s sense of profession in relationship to a work role. According to one paradigm model, an individual’s sense of identity is determined mostly by the explorations and commitments that she or he makes regarding certain personal and social traits (Marcia, 1966). In this framework, the identity of a nurse is determined by how that individual sees and experiences nursing. These definitions invariably go on to indicate that professional nurses are educators as well as managers, colleagues, mentors, researchers, and advocates for health. An understanding of all of these roles and their parallel identity characteristics is essential for a nurse to be successful. The nurse must also be grounded in the concept of other-centeredness as opposed to being egocentric. An exceptional demonstration of this other-centeredness is nursing’s central ethical doctrine, which holds that a nurse’s first obligation is to the patient (Siefert, 2009). Moral theorist and feminist thinker Carol Gilligan’s work speaks to the morality of care defining the preservation of relationships as the highest level of moral reasoning. From her perspective of the nature of moral development, nursing based on other-centeredness represents the final stage in moral development. What underlies the skill and knowledge of professional nursing is caregiving, empathy, and compassion (McFadden, 2006). Embedded within this overarching construct of the role of the nurse with an identity of other-centeredness are seven key dyads that are essential to any exploration of nursing. These roles and the corresponding identity characteristics that infuse these roles (Figure 4-1) constitute an overlapping mosaic that is not exclusive but is foundational to the professional role of nurse. This mosaic of nursing role and identity dyads can be viewed as role progression as professional experience ensues. If the act of caregiving drives the health care delivery role, compassion is an essential identity characteristic that guides the actions of assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation. When asked about the most important role of a nurse, most nurses respond with one word: caregiving. The nursing profession is grounded in the phenomenon of caring (Leininger, 1988). Leininger discovered that patients from diverse cultures valued care differently than nurses did. Gradually, Leininger became convinced of the need for a theoretical framework to discover, explain, and predict dimensions of care and developed culture care theory, the only nursing theory that focuses on culture, (Leininger & McFarland, 1997). This theory defines caring behaviors on the part of a caregiver as those that are congruent with the beliefs, values, and expressions of the care recipient. Similarly, Jean Watson’s theory of caring describes the scientific basis of nursing as extending beyond human interaction, to a moral concern for preserving human dignity and respect for the wholeness of the care recipient (Childs, 2006). Both of these theories demonstrate the link between the caregiver role and the identity characteristics of compassion and empathy. Caring is an essential feature of the profession, one that is central to a nurse’s identity and that serves to facilitate health and healing: “The culture of caring, as a fundamental part of the nursing profession, characterizes both concern and consideration for the whole person, a commitment to the common good and health of all, and outreach to those who are vulnerable.” (National League for Nursing, 2009, para 1). Because of this fundamental maxim, preparing the nurse for the caregiving role is an established practice in nursing education. What is more difficult to engender, however, but nonetheless as fundamental, is fostering caring through compassion. Although “teaching” identity is a complex process, nurses need to be awakened to and evaluated on the emotions prompted by the pain and suffering of others. Grounded in the development of empathy, caring is the vigorous attempt not only to feel another’s pain but to take steps to alleviate suffering and to seek the wellness within that person. Covington (2005) states, “Caring presence is mutual trust and sharing, transcending connectedness, and experience. This special way of being, a caring presence, involves devotion to a client’s well-being while bringing scientific knowledge and expertise to the relationship” (p. 169). Kathy Robinson (2003), former president of the Emergency Nurses Association, writes, “No technology in health care replaces the critical thinking of a human mind, the caring of a human soul, the proficiency and skill of a human hand, and the warmth of a human heart in healing the sick and injured. That is nursing, esteemed colleagues; that is you” (p. 200). The role of nurse as colleague is not only essential to collaborative clinical and research practices, but integral to the team process in dynamic health care. Working together toward common purposes, improving health, respecting shared strengths, caring and compassion—these are fundamental to the profession. For example, in 2009, 90% of American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) members responding to a survey reported that they were colleagues with physicians and administrators and that they believed this was among the most important elements in creating a healthy work environment (Morton & Fontaine, 2009). At the heart of being a colleague is the ability not only to cooperate, but to actively collaborate. Collaboration is a multifaceted process of working together to accomplish a common goal; it involves a mix of differing viewpoints to better comprehend a challenging issue. Arising between true colleagues, collaboration is the ability to be innovative in achieving consensus to achieve shared goals. According to Gardner, there are 10 lessons in collaborations: (1) know thyself; (2) learn to value and manage diversity; (3) develop constructive conflict resolution skills; (4) use personal power to create win-win situations; (5) master interpersonal and process skills; (6) recognize that collaboration is a journey; (7) leverage all multidisciplinary forums; (8) appreciate that collaboration can occur spontaneously; (9) balance autonomy and unity in collaborative relationships; and (10) remember that collaboration is not required for all decisions (Gardner, 2005, Section 3). Interprofessional collaboration is a vital aspect of plans designed to increase the effectiveness of delivery of health care (Morton & Fontaine, 2009). According to Dorrie Fontaine, RN, PhD, FAAN, former president of the AACN, “Escalating financial pressures and alarming workforce shortages make it imperative that physicians and nurses actively work together to establish new patient-focused practice models. The combined efforts of the AACN and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) will establish a strong leadership force in effecting meaningful change in our hospitals and health systems on behalf of the critically ill patients we serve” (Robinson, 2003, para 6). From initiatives to promote interdisciplinary education in health care to institutes focusing on fostering dynamic international collaboration involving nursing, medical and allied health researchers, clinicians, academics, and quality managers, collaboration among colleagues has emerged as vital to professional nursing. An example of an important new arena for collaborative practice for nursing is the rapid advance of telehealth as a critical vehicle for health care delivery, especially in rural underserved communities. Telehealth is the exchange of medical and other health information via electronic communications from one site to another with the intent of addressing patient needs. Through telehealth, colleagues provide medical, nursing, or other health care to a remote location. The remote site almost always requires a nurse to be present with the patient to present the history and physical, provide clinical interventions, offer health education, and ensure follow-up. This is collaborative practice in its highest form, because the role of the nurse in this setting is to leverage technology and nursing expertise to provide quality health care (Cattell-Gordon, 2009). A leader is someone grounded in the core value of compassion with the capacity to inspire mentorship, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking. To communicate this leadership, the leader must provide the framework from which complex problem solving evolves. A core element of managing and leading is understanding the nature of servant leadership and possessing emotional intelligence (Triola, 2007). Nurse leaders demonstrate these identity characteristics when they set priorities based on the needs of those they are leading and are committed to the professional growth of others. Effective leadership is vital to creating healthy work environments that are conducive to promoting quality patient outcomes and health for staff. Authentic leadership, according to Kathleen McCauley, former president of the AACN, is the “glue” needed to hold together a healthy work environment. In some settings, a nursing culture with a focus on task orientation, rigid hierarchical structures, and the possible disempowerment of staff is an impediment to delivery of compassionate patient-centered care. As a nurse leader, if one sets the tone of joining with the patient in a process of compassionate collaboration, outcomes in health will be more optimally achieved (Jonsdottir, Litchfield, & Dexheiner, 2004). The role of the educator is essential to the overall function and identity of the nurse. In the complex world of contemporary health care, as patients seek to manage their disease and cope with illness, the nurse assumes the primary role of educator. At every level, the patient educator role exists within the scope of practice because it significantly affects a patient’s health and quality of life. The process of providing education parallels the nursing process, with the first step being an assessment of the learner’s needs, readiness to learn, and learning style, followed by an individually designed intervention, and completed only when the outcome has been evaluated (Bastable, 2007). The ability of nurses to effectively provide health education is essential in addressing local and global health problems. To be effective as a teacher requires a commitment to be a learner; to see teaching and learning as the act of guiding; and to understand the essence of the phrase “to educate.” As John Dewey posits, learners grow in concert with others: “Every experience lives on in further experiences. Hence, the central problem of … education … is to select the kind of present experiences that develop fruitfully and creatively in subsequent experiences” (Dewey, Kilpatrick, Hartmann, & Melby, 1937, p. 45). The role of educator in the profession of nursing is based on the desire to help individuals and communities grow. The nurse educator is in essence nurturing a relationship, sharing knowledge, and empowering individuals, families, and communities. The nurse in this role can actively teach and guide patients, families, and communities about health/wellness and illness—about living and dying. This role of the nurse as educator is further optimized by fostering personal knowing. It is the ability to be empathetic, to see an event from the perspective of another, and to recognize the other as a subject rather as an object. Personal knowing is the discovery of self and others, which is arrived at through reflection, synthesis of perceptions, and connecting with that which is known (Kaminski, 2006, p. 14). In addition to empathy, nurse educators strive to foster critical thinking skills in their students. Lemire (2002, p. 69) notes that in educating nurses for leadership, the educator must emphasize the cognitive and disposition aspects of critical thinking in order to promote active and sequential learning. Critical thinking and problem-solving skills are acquired over time through lifelong learning and experience. Mentoring refers to a formal or informal process in which a mentor and a mentee establish a relationship with the mutual goal of meeting the career goals of the mentee (Bally, 2007). One role of the mentor—to be true to oneself and guide another to greater personal awareness and skill—is crucial to retaining and encouraging nurses in the workplace. According to the literature, the initial 3 months of a newly graduated nurse’s transition is vital to long-term success in the profession (Winfield, Melo, & Myrick, 2009). This initial transition involves an all-encompassing transformation of roles and responsibilities, an acceptance of the differences between the theoretical orientation of the nurse’s education and the practical focus of professional work, and an integration into an environment that emphasizes teamwork as opposed to individually based care provision. The role of the professional nurse as caregiver, leader, teacher, colleague, and mentor is a critical one in helping newly graduated nurses or any nurses who change roles to feel successful in their new environment (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). Because nursing excellence is embodied in the combined competency of skills and practice, the experienced mentor, grounded in the spirit of nurturing, is crucial to the development of careers, collaborative networks, and a contagious enthusiasm within the profession. For this enthusiasm to take hold, the mentor must be a person whom the mentee can trust. The mentor acts as a “role model and advocate to pass on life experiences and knowledge in order to motivate, support and enhance their mentee’s personal and career development” (Kuhl, 2005, p. 9). Building on this, the key qualities in an effective nurse mentor reflect the identity characteristics of the role modeling and sharing. The National League for Nursing (NLN), one of the membership organizations for nurse faculty and leaders in nursing education, states, “Experienced nurses everywhere have the opportunity to become mentors for other nurses. Mentoring another nurse is a professional means of passing along knowledge, skills, behaviors and values to a less experienced individual” (NLN, 2006, p. 10). The NLN further asserts that in a positive sense, the act of mentoring gives nurses an opportunity to create a legacy. By sharing information and insights with members of their own profession, experienced nurses can enable others to maximize their potential, thereby improving patient care and ultimately strengthening the profession of nursing (Henk, 2005). The role of researcher in the nursing profession is vital for generating new knowledge to underpin nursing practice, clinical care, and public health. As both a caring art and scientific enterprise, nursing has an obligation to provide care that is continually examined through research (International Council of Nurses, 2009). Nurses working as independent investigators or in multidisciplinary research teams offer new insights and unique perspectives to the process. According to Patricia Munhall from the NLN, nurses change in “how” they believe in something rather than “what” they believe and states, “The sands of science itself are shifting, as more and more scientists, including nurse scientists, realize that science cannot be a field of absolute and final truth but is an endeavor focused on illuminating an ever-changing body of ideas” (Munhall, 2007, p. 12). Nursing research, in fact, is critical to the emergence of community-based participatory research, an approach in which the scientific process is applied to a collaborative process with the community of interest. To be successful in the role of nurse researcher, the identity of the researcher must be grounded in curiosity and the desire for discovery driven by compassion for human suffering. This identity, in turn, empowers patients because it is not proprietary knowledge but rather is about sharing and inspiring new knowledge. Further, curiosity creates an interest in learning and guiding that helps break down barriers between cultures. The curious nurse researcher asks important “how” and “why” questions and builds essential stepping stones toward awareness, appreciation, and understanding of other cultures. Through curiosity, people can gain new perspectives, unparalleled learning and growth, and a chance for interesting conversation and reflection at every interaction (Kaminski, 2006).

Professional Nursing Roles

![]() Nursing Roles, Functions, and Characteristics

Nursing Roles, Functions, and Characteristics

NURSING ROLE STEREOTYPES

ACTUAL NURSING ROLES

PRAXIS AND THE NURSING META-DYAD

ESSENTIAL ROLE FUNCTIONS AND CHARACTERISTICS

Caregiver—Caring, Compassion, and Empathy

Colleague—Collaborating and Connecting

Manager—Leading, Inspiring, Thinking Critically

Educator—Learning and Guiding

Mentor—Sharing and Role Modeling

Researcher—Inquiring and Discovering

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Professional Nursing Roles

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access