CHAPTER 3 Professional negligence and vicarious liability

Negligence as part of the law of civil wrongs

As explained in Chapter 1, an understanding of the law and how it operates requires, in the first instance, that the distinction be made between the criminal and civil law. Once that has been done, it is then necessary to further divide the civil law into a number of different areas; for example, family law, workers compensation, industrial law and so on. One of the most important areas of the civil law is known as the law of civil wrongs, sometimes known as the law of torts. There are a number of civil wrongs or torts, the most widely known being negligence. Two other examples of well-known civil wrongs are nuisance and defamation. The legal principles that apply in these areas are essentially the well-established common-law principles that have been developed by the courts over the centuries. In some instances, however, parliament has supplemented the common-law principles with legislation. As an example, the initial common-law principles relating to civil defamation have now been either supplemented or replaced by the passing of specific legislation (generally known as the Defamation Act) in each state or territory.

Legislative changes affecting the law in relation to civil negligence and professional negligence in particular

The award of damages for personal injury has become unaffordable and unsustainable as the principle (sic) source of compensation for those injured through the fault of another. It is desirable to examine a method for the reform of the common law with the objective of limiting liability and quantum of damages arising from personal injury and death.1

… develop and evaluate options for a requirement that the standard of care in professional negligence matters (including medical negligence) accords with the generally accepted practice of the relevant profession at the time of the negligent act or omission …2

In bringing a claim alleging professional negligence, it is necessary to have regard to the legislative changes that have occurred in each state and territory relevant to such a claim consequent upon the recommendations of the Ipp Report. The relevant legislation in each state and territory is set out in Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1 Legislation relevant to a claim alleging professional negligence

| New South Wales | Civil Liability Act 2002 |

| Victoria | Wrongs Act 1958 |

| Queensland | Civil Liability Act 2003 |

| South Australia | Civil Liability Act 1936 |

| Western Australia | Civil Liability Act 2002 |

| Tasmania | Civil Liability Act 2002 |

| Northern Territory | Personal Injuries (Liabilities and Damages) Act 2003 |

| Australian Capital Territory | Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 |

Professional negligence in a healthcare context

The categories of negligence are never closed. The cardinal principle of liability is that the party complained of should owe to the party complaining a duty to take care and that the party complaining should be able to prove that he [sic] has suffered damage as a consequence of a breach of that duty.3

Negligence: Principle 1 — the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care

Duty of care as a nurse

It has long been determined by the courts that, as far as your professional activities at work are concerned, a duty of care is owed to patients and fellow employees. In a historic decision given in 1932, the English House of Lords (then a superior court of appeal whose decisions bound Australian courts) laid down the now well-established principles concerning the existence of the duty of care.4 The case for final determination by the House of Lords concerned an action that arose when the plaintiff had consumed a bottle of ginger beer that contained the decomposed remains of a snail. She brought an action against the manufacturer alleging, among other issues, that the manufacturer owed her a duty of care in the manufacture of its product. Today, the existence of such a duty would not even be put in issue and the authority for that proposition is the principle laid down in the case under discussion. The significance of the decision can therefore readily be appreciated as a milestone in the development of the law in this area.

… persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have had them in my contemplation as being likely to be damaged when I set out to do the acts or omissions which are now being complained of.5

What is the position outside of work?

public authorities, particularly those which provide or manage services for the general benefit of the community, or exercise regulatory functions

public authorities, particularly those which provide or manage services for the general benefit of the community, or exercise regulatory functionsThe standard of care expected of nurses acting in a professional capacity

It is not possible to give a list of predetermined guidelines as to what is or what is not reasonable in every conceivable incident that may arise. What is or is not reasonable depends on the facts and circumstances of each individual case. For example, an emergency situation would be quite different from a routine ward situation, and intensive care would be quite different from the outpatients’ department — hence the necessity for the objective standard. A registered nurse working in an intensive care unit is presumed to have the skills, knowledge and expertise that would be expected of a registered nurse working in an intensive care unit. Likewise, an enrolled nurse in a particular clinical situation is presumed to have the skill, knowledge and expertise expected objectively of an enrolled nurse in that particular clinical situation.

Legislative provision to determine the standard of care

Given that the approach to determining ‘standard of care’ refers to a professional standard that is ‘widely accepted in Australia by peer professional opinion’, it is clear that in establishing the requisite standard of care in relation to particular facts and circumstances, evidence would be elicited, amongst other sources, from one’s professional peers.

Other sources of evidence

Departmental guidelines and/or employer policy and procedure directives

More often than not, the respective state or territory and Commonwealth departments of health issue numerous policy circulars, many of which are of direct relevance to nurses in their day-to-day work. Such policy circulars very often lay down procedures and practices to be observed and enforced in given clinical situations and are generally issued as a clear indication of the standards to be observed in such situations.

Professional standards of practice

The courts in Australia and overseas have on occasions seen fit to specifically refer to documented practice and procedure standards as well as nursing standards documents as evidence to assist them in determining the standard of care expected of a nurse in a given situation. A very good example where the court relied on professional standards document was in the case of Langley v Glandore — a decision of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Queensland.6 The full details of that matter are set out later in this chapter.

The relevant established standard for counting of sponges, swabs, instruments and needles is called the ‘ACORN’ standard and it supports the description of the duties that has been outlined. Importantly, there was no dissent at the trial concerning its applicability.7

As well, a recent Canadian case used the standing orders of an emergency room as the standard against which medical and nursing practice should be measured.8 In another Canadian case, an entire section of the procedure manual was reproduced in the judgment as it was considered crucial to determining the question of whether or not the practice under review had fallen below the standard which could reasonably have been expected.9

It may be seen that the Board in reaching its decision that the Appellant had been guilty of unprofessional conduct, had regard to the various standards of nursing practice which had been laid down by its own guidelines; the policy of the nursing home, regulations, the International Council of Nursing’s Code of Ethics and what it describes as the ANRAC competencies. It may be accepted that those standards are well recognised and accepted in the nursing profession.10

Example 1: Coroner’s inquiry into the death of Tracey Baxter, 1979

Facts

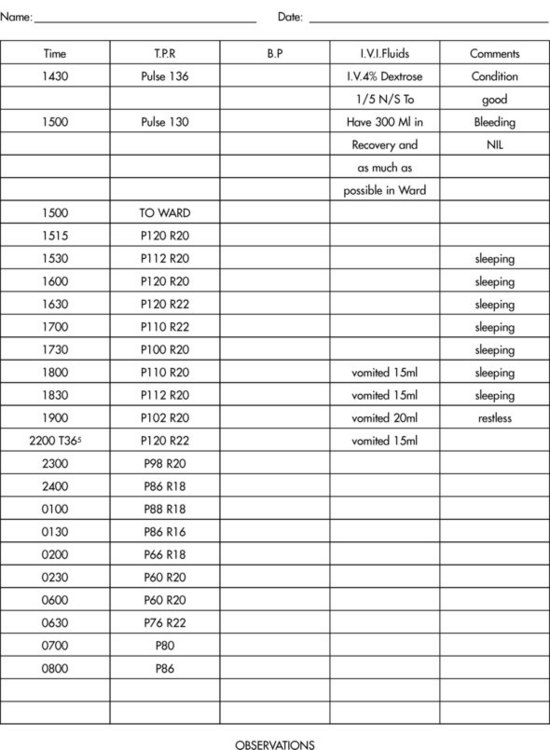

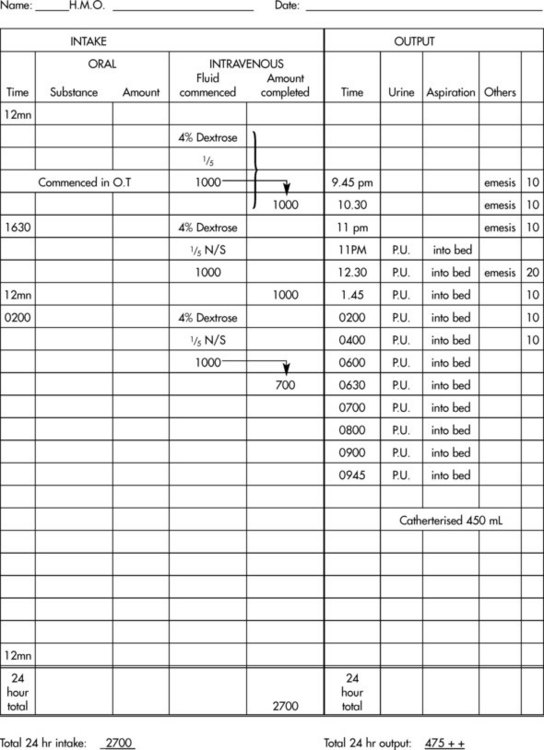

A 6-year-old child was admitted to hospital for a routine tonsillectomy. The operation was performed at the commencement of the afternoon list and the child was in the recovery room of the operating theatre at approximately 2.30 p.m. Prior to surgery an intravenous line was inserted and during the operation the child received 300 mL of normal saline. At the conclusion of the operation the surgeon wrote on the intravenous fluid order chart that the child was to continue to receive 100 mL per hour of a dextrose/saline solution. The registered nurse in the recovery room commenced an observation chart on the child (Figure 3.1), but not a fluid balance chart. That was commenced by the registered nurse in the children’s ward on the child’s return (Figure 3.2). The registered nurse in the recovery room, apart from noting some preliminary pulse rate readings, also wrote the initial comment concerning the intravenous fluids to be given to the child. That comment read, among other things, that the child was to have ‘as much as possible in ward’.

The child returned to the ward at approximately 3 p.m. and the fluid balance chart was commenced and observations continued. A glance at the fluid balance chart in Figure 3.2 will reveal that at 4.30 p.m., some 1½ hours after the child’s return to the ward, a further litre of the dextrose/saline solution was commenced. This litre went through by 2 a.m. the next day, and a further litre was commenced by the registered nurse on night duty. The fluid balance chart does not reveal when that litre was intended to be completed but it does reveal that by sometime later that morning (approximately 9 a.m., as best determined in court) the child had received 700 mL of that litre. The total intravenous fluid intake of the child from the time of the operation to 9 a.m. the next morning was 3 litres — remembering the 300 mL of normal saline that was never entered on the fluid balance chart.

The child’s observations were continued spasmodically, as the observation chart reveals, and there were occasions when no observations were taken for some hours. A critical examination of the pulse rate in Figure 3.1 shows a slow but steady decline, and a relevant section of the nurse’s notes reveals that the child’s pulse rate went down to as low as 48 on at least one occasion.

Comment

At the coroner’s inquest which followed, the major allegation raised by the relatives’ legal representative was that the real cause of the child’s death was the excess fluid negligently administered to the child by the nursing staff. It was stated that the excess fluid resulted initially in cerebral oedema with attendant cerebral irritation, eventual grand mal fitting, electrolyte disturbances, cardiac arrhythmia and finally cardiac arrest. Allegations of mismanagement were also levelled against the medical officers involved, because of their failure to detect the fluid overload as the cause of the child’s problem and deal with it. Certainly, in the absence of any other extrinsic evidence as to the cause of the child’s death and the expert medical evidence presented in support of such a proposition, it would appear that the excess fluid given to the child played a major role in the child’s death. Even assuming that it had not, this unhappy episode serves to illustrate very clearly the standard of care that is expected of nursing staff.

The child’s fluid intake and the fluid balance chart

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would write ‘as much as possible in ward’ as a patient’s IV fluid order?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would write ‘as much as possible in ward’ as a patient’s IV fluid order? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse working in a children’s ward would accept such an order as appropriate?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse working in a children’s ward would accept such an order as appropriate? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would seek clarification of such an order from the medical officer immediately?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would seek clarification of such an order from the medical officer immediately? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would know the normal fluid balance requirements of children?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would know the normal fluid balance requirements of children? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would know that 3 litres of fluid in 20 hours would be an excessive amount of fluid to give to a child of 6 in most situations?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would know that 3 litres of fluid in 20 hours would be an excessive amount of fluid to give to a child of 6 in most situations?In our view, the answers to the questions posed are self-evident. Using this example, it is important to appreciate that, as far as the law is concerned, it would be expected that a registered nurse who is nursing children or infants would be aware of the different fluid balance requirements of children. It would not be expected that the precise requirements of every age and weight be known by rote, but that a general knowledge of the difference be known which should cause nursing staff to be aware of the need to carefully check the fluid balance regimes of children. It would be argued that a registered nurse would have received such knowledge as a result of the education program undertaken to become a registered nurse. Accordingly, if a registered nurse is going to work in a paediatric area, the law would presume as being reasonable and part of her profession that the nurse not only has the knowledge but applies it.

The child’s observations and the observation chart

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would not only record the child’s pulse rate but also note the steady drop in the rate?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would not only record the child’s pulse rate but also note the steady drop in the rate? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would notify the medical officer of the drop in the pulse rate?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would notify the medical officer of the drop in the pulse rate? Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would be alarmed or concerned at the signs and symptoms being exhibited by the child — for example, ‘pupils still dilated’ — bearing in mind she was a post-tonsillectomy patient?

Would it be considered widely accepted as competent professional practice by peer opinion that a registered nurse would be alarmed or concerned at the signs and symptoms being exhibited by the child — for example, ‘pupils still dilated’ — bearing in mind she was a post-tonsillectomy patient?Once again the answers to the questions posed are self-evident. One of the major tasks of nursing staff is to take and record observations on a patient so as to indicate the present state of the patient’s clinical condition and to act as an indicator of any worsening or improvement in that condition. As a result of such observations, together with other methods of clinical investigation, a patient’s treatment and/or medication is generally determined. It goes without saying that a nurse’s responsibilities in this area are significant. Important as the taking and recording of a patient’s observations are, what is more important is understanding the significance of those observations. Equally, as far as the law is concerned, a registered nurse would, generally speaking, know the significance of the observations she is taking and recording; that is, what is normal and what is abnormal having regard to the patient’s condition. Such knowledge would be presumed to have been received as part of the registered nurse’s education and training. If the registered nurse is presumed to have such knowledge it must follow, as a matter of commonsense, that, in the presence of abnormal observations, widely accepted professional practice would be that the nurse concerned would notify the appropriate medical officer or senior nursing staff. That is the standard of care that would be expected in such circumstances.

Example 2: Sha Cheng Wang (by his tutor Ru Bo Wang) v Central Sydney Area Health Service11

Facts

In his treatment at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Mr Wang was attended to by a registered nurse.

Mr Wang was seen on arrival by the triage nurse, Registered Nurse Carruthers, who obtained a brief history and undertook a brief physical examination of him. Her entry in the patient notes read simply ‘assaulted ? LOC’ and she explained that the expression ‘? LOC’ meant a possible loss of consciousness. There was no other notation made of any other neurological observations undertaken by Nurse Carruthers, although she gave evidence that, as part of her initial examination of Mr Wang ‘he walked into her office unaided and appeared to be alert. She had him squeeze her fingers to test his hand grip, which she found to be firm and equal. She checked his pupils by having him close his eyes and open them quickly, and they appeared to be equal and reacting to light’. It should be noted at this point that the judge hearing the matter concluded that he found the evidence of Nurse Carruthers ‘unreliable in certain respects’.12

At about 10.00 p.m., Nurse Carruthers was relieved by Registered Nurse Jennifer Smith. Evidence was given that one of Mr Wang’s companions subsequently approached Nurse Smith to enquire how much longer Mr Wang would have to wait to be treated. He was told that the department was busy and that a lot of people were waiting. About 15 minutes later he asked her if they could go somewhere else for treatment, perhaps at a private hospital, and she said that they were free to do so. As he put it, she said that ‘we can do whatever we want to’.13

He advised Mr Wang he should return to the hospital for an X-ray. This was rejected because of the displeasure at what had occurred earlier.

He advised Mr Wang he should return to the hospital for an X-ray. This was rejected because of the displeasure at what had occurred earlier. Dr Katelaris gave them a ‘head injury advice form’ and went on to explain what it said, using gestures to ensure that he was understood. He said that an ambulance should be called immediately in the event of vomiting or convulsion, if the plaintiff became drowsy or unrouseable, or if they observed weakness in one or more of his limbs or inequality in the size of his pupils. He told them that the plaintiff should not be left alone. He advised them to take him to a Chinese-speaking doctor the next morning to arrange for an X-ray and for any ongoing care which might be necessary.

Dr Katelaris gave them a ‘head injury advice form’ and went on to explain what it said, using gestures to ensure that he was understood. He said that an ambulance should be called immediately in the event of vomiting or convulsion, if the plaintiff became drowsy or unrouseable, or if they observed weakness in one or more of his limbs or inequality in the size of his pupils. He told them that the plaintiff should not be left alone. He advised them to take him to a Chinese-speaking doctor the next morning to arrange for an X-ray and for any ongoing care which might be necessary.Comment

Mr Wang’s case against the hospital was put on two alternative bases. Firstly, it was alleged that Nurse Carruthers’ examination was inadequate and superficial and that no notice was taken of his friends’ insistence that Mr Wang needed urgent attention, so that Mr Wang was not afforded the priority which he deserved. Alternatively, accepting that his priority was appropriately assessed, Nurse Carruthers should have consulted a doctor about him before she went off duty and Nurse Smith should have done so before the plaintiff left the hospital. In either event, it was said, some attempt should have been made to dissuade Mr Wang from leaving before he had been seen by a doctor.

… it is clear that her task as triage sister was to make a primary assessment of him with a view to assessing the urgency of his need for the treatment. That assessment had to be made in the light of the other demands upon the Department at the time and the available professional resources … Sister Carruthers’ other responsibility was to keep the plaintiff under observation in the waiting area in case his condition worsened.14

It was common ground that the plaintiff was free to leave and the hospital staff had no power to restrain him. However, varying views were expressed by the experts about how the situation should have been handled. Ms Fares said that normally staff would attempt to persuade a patient from leaving and would find out how soon a doctor might be available, informing the medical staff that the patient was becoming restless.15

Another expert medical witness accepted by the judge gave evidence that:

… when patients decide to leave an emergency department without treatment, staff should attempt to discourage them from doing so. Failing that, they should try to ensure that they seek alternative medical care. The practice in the hospital where he worked was that, if it was clear that a patient could not be persuaded to wait, he or she would be given the names of medical clinics in the area … the approach of staff to the situation must be flexible and would depend on a number of variables, including the clinical presentation of the patient, where the patient intended to go upon leaving, the demands upon the resources of the department at the time, the availability of other medical services in the area and their capacity to deal with the patient’s condition.16

Given the unpredictable effects of head injuries, it was clearly in the plaintiff’s best interests to remain at the hospital, where there were the resources to observe and respond to any deterioration of his condition. I am satisfied that, if he had, he would not be in his present predicament.

The Central Sydney Area Health Service, which administers the hospital, is a statutory authority whose duty was to take reasonable care for the plaintiff’s wellbeing in the circumstances, within the limits of its resources. In my view, that duty extended to furnishing the plaintiff with appropriate advice when it was intimated that he might leave the hospital. The hospital failed to discharge that duty, and the plaintiff’s present condition is attributable to that failure.17

Example 3: McCabe v Auburn District Hospital18

The incident giving rise to this decision occurred in a public hospital in New South Wales in 1981. The case is also referred to in Chapter 7to highlight the importance of proper record keeping by nursing staff.

The relevant facts are set out below.

Facts

Mr McCabe was a 21-year-old man admitted to hospital for an emergency appendicectomy. Post-operatively he did not make the expected uneventful recovery. He could not keep food or fluids down, he developed diarrhoea and a spiking temperature pattern, and he complained of excessive abdominal pain. A chest X-ray and a microurine were ordered and proved negative. On the morning of the fifth post-operative day, which was a Saturday, the registrar was doing his rounds prior to going off duty but remaining on call at home over the weekend. The patient was still exhibiting the same symptoms. The registrar ordered a full blood count to be done that morning. The blood was taken and the result returned to the ward that afternoon after the registrar had left the hospital. The result disclosed a significantly raised white cell count and other abnormal readings indicative of some form of severe infection. The registered nurse on duty filed the pathology result in the appropriate place in the patient’s record and did not attempt to contact the registrar. Likewise, at no time during the weekend did the registrar ring the ward to ascertain Mr McCabe’s results. None of the other registered nurses who came on duty that weekend noticed the pathology result.

I am of the view that the hospital notes are not, in the current case, reliable. In particular there is unreliability in recording the manifest and observable continuing deterioration of the deceased’s condition. I am satisfied that the routine temperature checks even if accurate as to scale were accompanied by failure to note what was there to be seen, namely that the deceased was perspirant and ‘hot’. This was evident even to non-medical appreciation … I do conclude … that there were things significant in assessing the patient’s deterioration which were overlooked and the written record simply does not truly reflect the currency of events.19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree