Principles and Procedures for Nursing Care of Children

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Identify psychosocial considerations unique to children undergoing selected procedures.

• Describe techniques useful for eliciting cooperation from the child undergoing selected procedures.

• Describe step-by-step nursing actions and the rationales for performing selected procedures.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Children need preparation before and accurate information about any procedure that is performed. This information is essential to promote a sense of security, decrease fear, elicit cooperation, and improve coping skills. Parents also need preparation because their anxiety about a procedure may be transferred to the child. Teaching before performing procedures increases the knowledge base of the child and family.

After assessing the child and family, the nurse needs to plan how to carry out the procedure in the most effective manner. The nurse can implement strategies to help the child and parents through all phases of a procedure: the anticipation and preparation phase, the actual procedure, and the recovery period after completion.

Preparing Children for Procedures

Preparing children and families for procedures, especially those that are painful, threatening, or invasive, starts with a thorough, individualized assessment. This process should include an assessment of the child’s developmental stage, personality, existing level of knowledge, present level of understanding, past experiences, coping skills, and family situation. The nurse can then match explanations and teaching to the specific needs of the child and family. It is also important for the nurse to determine the communication approaches that will be most effective for the child and family based on the child’s age and developmental level as well as the family’s cultural preferences (see Chapter 4 for more information about communication).

Explaining Procedures

Before starting the process of preparing the child and family for a procedure, it is important for the nurse to review all the elements and hospital policies, if applicable. This is especially important if the procedure is new or performed infrequently. The nurse requests any needed medication for the child, gathers all supplies, and obtains assistance as necessary. Equipment is obtained and tested to ensure that it functions properly before beginning any procedure.

Explaining procedures includes demonstrating equipment and describing anything the child will feel, see, hear, and smell. The nurse uses a developmentally appropriate approach and words the child will understand. Relating the experience to an object, or situation familiar or of interest to the child is an effective communication strategy.

Appropriately timing the explanation is critical. Many children respond better to procedures if the explanation is given either just before the procedure or step by step as the procedure unfolds. Some older children and adolescents like to be prepared well in advance in case they have questions and need more information. Advance preparation allows the child to express feelings about the procedure verbally or through role playing. Parents know their child best, so the nurse asks parents about the best timing and approach to use. Time should be allowed for the child to become familiar with the equipment and for the child and family to ask questions (Box 37-1).

Also important for a child’s successful coping with an invasive or painful procedure is the presence of someone the child trusts. Time spent establishing a trusting relationship with a child is time well spent. Trust in health care providers can enhance the child’s unique coping strategies.

Before procedures, ensure the child’s privacy by closing the door to the room and drawing a curtain around the bed or, optimally, by taking the child to a treatment room if appropriate and comfortable for the child and parent. The treatment room contains suitable equipment for invasive procedures and is a private area away from the safe haven of a child’s room or the playroom (Figure 37-1). Visitors should be asked to leave, and parents might also choose to leave, although parental participation is supported and encouraged.

Telling children and parents in advance what they can and should do during the procedure provides a sense of control and decreases potential feelings of powerlessness. For example, a child who is having an intravenous (IV) catheter placed or a blood specimen drawn is told that to “help,” he or she must hold an extremity still and not move. Parents are asked to “help” the child remember to not move.

The nurse offers children choices when feasible. For example, a child is allowed to choose the type of colorful bandage that will cover an injection site or whether to have a procedure done before or after the next television show. Children are never threatened with punishment if they fail to cooperate. Nurses need to have realistic expectations that are based on the child’s developmental level and capacity for cooperation.

Parents are encouraged to be involved as much as they want according to what is possible during procedures. For example, a child might be much more cooperative in taking oral medications if the mother administers them. Often, by explaining what the parents will be seeing and what they can do, the nurse helps them feel comfortable staying with and supporting their child. The nurse should recognize, however, that parents might be uncomfortable remaining with their child during a painful or invasive procedure. The nurse gives parents permission to leave if they desire and assures them that they will be called if they are needed or as soon as the procedure is completed.

Consent for Procedures

All surgical or diagnostic invasive procedures, particularly those that involve risk to the child, require informed consent. Some examples are lumbar puncture, chest tube insertion, and bone marrow aspiration. Both legal and ethical requirements exist to inform the child, if appropriate, and the child’s parents of the benefits and risks of the proposed procedure or treatment. Informed consent must be obtained from the parent or legal guardian before the procedure is performed.

Other procedures, such as IV line insertions, specimen collection, and medication and oxygen administration, are covered under the general consent to treat that is signed at admission. It is now also customary to obtain assent from children 7 years old and older. Assent means that the child has been fully informed about the procedure and concurs with those giving the informed consent. Laws on informed consent vary from state to state, so nurses should become familiar with the laws, and the policies of their institution. (See Chapter 1 for information related to consent and other legal issues.)

The person performing the procedure should obtain the consent. Nurses need to check that the consent form is signed and witnessed, and they need to answer questions relating to the procedure. Occasionally an emergency or life-threatening situation arises in which contacting the parents or legal guardian for consent is not possible. In such cases, administrative consent may be obtained to allow physicians to perform the indicated procedures. (See Chapter 1 for legal issues related to emergency consent provisions.)

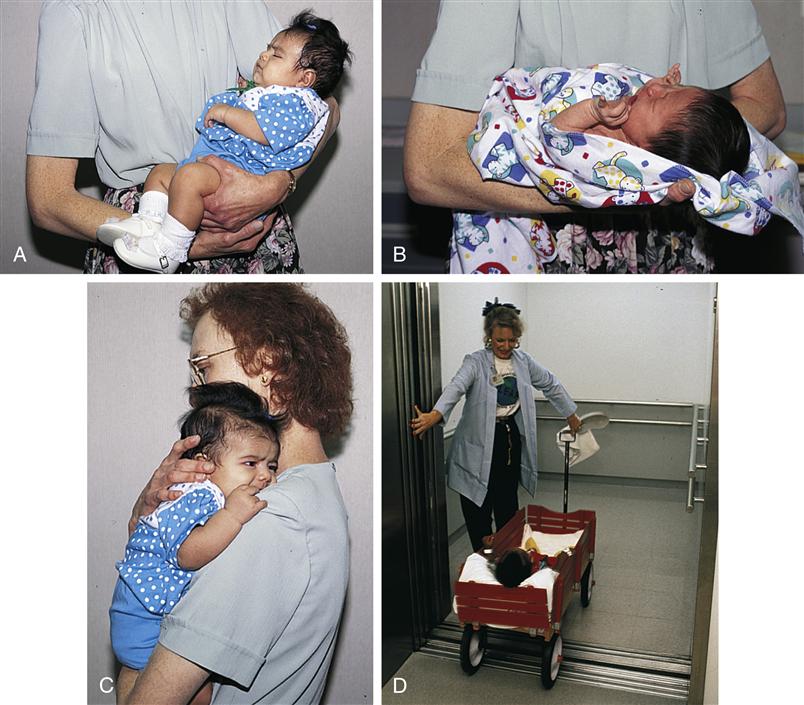

Holding and Transporting Infants and Children

Infants can be held in several positions (Figure 37-2). Before the infant is discharged from the hospital, the nurse teaches new parents how to hold the infant, and nurses working on pediatric units should hold infants in similar ways. Nurses hold infants securely, anticipating sudden movement. Because infants younger than 4 months old do not have well-established head control, supporting the head and neck is essential. Infants up to 2 to 3 months of age are cradled by holding them in a horizontal position, supporting the back, and grasping the thigh (see Figure 37-2, A). When using the football hold, the infant is tucked between the nurse’s body and elbow, with the arm carrying the infant’s body and the hand supporting the head (see Figure 37-2, B). When carrying the infant upright, the infant erect against the nurse’s chest (see Figure 37-2, C). The infant’s buttocks rest on the forearm, and the other arm supports the infant’s head and shoulders. Even for infants with well-developed neck muscles and head control, this extra support prevents infants from falling backward should they make a sudden move. Parents who use backpacks or front-facing baby carriers are advised to be sure that the infant’s head is supported at all times when in the backpack or carrier.

Hospitalized infants and children sometimes must be transported to other areas within a hospital unit or even outside the unit. A change in location might be a response to changes in the child’s condition or might be done to increase parental involvement in the child’s care (e.g., rooming-in). Children might be transported to different areas on the same unit (e.g., treatment room, playroom) or other hospital departments for specialized care (e.g., rehabilitation) or for diagnostic testing.

The method of transportation will depend on the child’s age, developmental level, and physical condition; the destination; safety factors; and whether equipment such as oxygen, an IV pump, or a cardiac monitor is needed to accompany the child. Any special accommodations should be arranged before the time of the planned transport.

Infants and toddlers can also be transported in a bassinet or crib. The rails should always be up in the highest position, and for older infants and toddlers the protective top should be in place. Strollers and wagons can be used to transfer older infants and toddlers to other areas on the unit (see Figure 37-2, D). Safety belts should be used, and the sides of the wagon should be in the raised position. An infant or a toddler is never left unattended in a wagon. With all transport methods, equipment is securely attached to a rolling cart or stand and then pushed or pulled along with the transporting vehicle. Equipment is not placed inside the transporting vehicle that infants or young children occupy.

Older children and adolescents are transported in wheelchairs or on stretchers with the side rails raised. In some cases, such as for a child in traction, transporting the child in the bed is preferable. Safety belts must be used and side rails must be in the raised and locked position. All children of all ages are supervised when in a transport vehicle.

Safety Issues in the Hospital Setting

Safety is of paramount concern for all children; infants and toddlers are at the greatest risk for injury. When an infant or toddler is in a crib, nurses and parents need to be especially vigilant about keeping crib side rails locked in the raised position to prevent the child from falling out of the crib. A hand is always placed on the back or abdomen of an infant or young child when the crib rails are down or when the small child is on an elevated surface such as a scale or treatment table. The nurse follows this practice consistently and teaches it to parents as well. As with adult patients, when children and adolescents are in hospital beds, they are maintained in the lowest position with the rails up on each side. Small objects, such as alcohol swabs and IV line caps, must be kept out of cribs and off of bedside tables, the floor, or any area within the young child’s reach. Older infants and toddlers may put these small items in their mouths, causing a significant risk for choking.

When performing a procedure on a child, techniques such as distraction by a parent or child life specialist, can facilitate the child remaining calm and unmoving (Sparks, Setlik, & Luhman, 2007). Occasionally, to prevent trauma during a procedure, holding a child is necessary to restrict movement. If holding is required, it is important to enlist the cooperation of the child (if appropriate age) and parent (Brenner, 2007). Some parents may be willing to hold their child on their lap for a procedure, or provide distraction while a second nurse holds the child. Parents should not be required to hold their child during a procedure, because this has been found to cause significant distress for the family (Brenner, 2007).

Restraints should be used only as a last resort for the protection of the child and others. Some infants and young children may require protection from pulling out a tube, removing a dressing, or disrupting a suture line by using a restraint. Thus, covering the hands with mitts, or using elbow restraints, which keep the elbows from bending so the child’s hands cannot reach a vulnerable site, may be used. If a restraint is needed for the child’s protection, most facilities require a physician’s order stating why any restraint is needed and how long it will be in place. The restraint chosen should be the least restrictive device that will prevent injury.

Before applying any form of restraint, the nurse informs the parents and child, if appropriate, the reason for the restraint, where it will be applied, what movement it will prevent, how long it will be in place, and how often a nurse will check on the child. The call button is made readily available so the child or parent can easily reach the nurse. The child’s developmental needs (e.g., thumb-sucking) are assessed, and provisions are made to meet these needs when possible (e.g., restrain a toddler’s arm so the thumb can still be placed in the mouth). Regardless of the type of restraint used, the nurse must remove the restraint and assess the patient on a regular and frequent basis (e.g., every 1 to 2 hours).

Many hospitalized children are physically active and may be at risk for injury from falls. There is considerable variability in how hospitals define, classify, and measure fall injury rates for children (Child Health Corporation of America, 2009). Factors that can contribute to children’s falls within the hospital setting include altered mental status (e.g., sedation, conditions that cause dizziness or confusion), age (younger than 3 years), need for mobility assistance, and inattentiveness by parents because of unfamiliarity with surroundings or anxiety (Razmus, Wilson, Smith, et al., 2006). It is recommended that all children undergo a complete fall risk screen when admitted to the hospital and again, if physiologic, motor, or sensory changes occur (Child Health Corporation of America, 2009). Children at risk for falls are then identified with identification bands on their wrists or ankles, signs, and stickers.

Nurses must ensure that children, parents, and other health care team members keep side and crib rails up. Infants or small toddlers can be placed in a crib with a plastic bubble top or higher extensions to the crib sides. Older children and adolescents at risk for falls are informed to not attempt to get out of bed without assistance and how to use the call system when they need help. Other preventive actions include keeping the floors free of objects and fluids, providing adequate lighting, using assistive equipment properly, wearing nonslip footwear, and frequent patient monitoring (Child Health Corporation of America, 2009). For active children, prevention strategies might include using a sitter to stay with the child, behavior modification techniques, such as a time-out, and diversional activities appropriate for the child’s developmental level and condition.

Infection Control

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is the mainstay of infection control in health care settings and in the home. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published data regarding transmission of organisms by health care workers in hospital settings. Using evidence based on research that demonstrates organisms are present both in hospitalized patients and on environmental surfaces, and that alcohol-based hand rubs are more effective for eliminating organisms, the CDC (2002) issued recommendations for hand hygiene, and these have been updated in a clinical guideline for preventing transmission of infection in the hospital (Siegel, Rhinehart, Jackson, et al., 2007):

Procedures described subsequently in this chapter assume that the nurse will use appropriate hand hygiene both before and after each procedure.

Standard Precautions

Standard Precautions, which are used in institutions and the workplace for infection prevention, apply to the following:

Two tiers of precautions are under this system. Standard Precautions, precautions in the first tier, apply in the care of all hospitalized patients without regard for diagnosis or presumed infectious state. Second-tier precautions apply in the care of specific patients and are referred to as Transmission-Based Precautions. They are for patients known or suspected to be infected by pathogens that are transmitted through air or droplets or through contact with dry skin or contaminated surfaces.

The complete guidelines for applying Standard Precautions and Transmission-Based Precautions are highly detailed and extensive (Siegel et al., 2007). Each facility is responsible for making these guidelines available and implementing the precautions. Procedures described subsequently in this chapter assume that the nurse will use appropriate Standard Precautions.

Implementing Precautions

When Transmission-Based Precautions are in effect, the items with which the infected child comes in contact are also contaminated. These items include the bed, linens, IV pump, sink, and toys. Therefore, the nurse who is going into the room to reset an IV pump, pick up soiled linens, and so forth must use whatever protective equipment is mandated by the type of precaution (e.g., gown, mask, gloves, goggles, face shield) (Siegel et al., 2007).

Children placed on Transmission-Based Precautions often need extra attention to avert boredom. They need more diversional activities, such as games or movies, and more psychosocial support. Young children, for example, may think that they are being punished. Visitors might hesitate to enter the child’s room and may need additional support or reassurance from the nurse.

Family Teaching

Family education is crucial for effective infection control or prevention. The nurse emphasizes to parents, visitors, and other health care providers that infection control precautions are important and must be closely followed. Parents often state that they are there to visit only their child and do not understand the need to wear special clothing or equipment. The nurse needs to emphasize that the organisms that cause some diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus, can live on inanimate objects such as clothing or crib rails for many hours. Thus, the disease can spread throughout the hospital or to the home if infection control or prevention measures are not followed. Family members are encouraged to visit the child frequently because visits will decrease the child’s sense of isolation. Family are taught that meticulous hand hygiene, both in the hospital setting and at home, is the best way to prevent infection.

Bathing Infants and Children

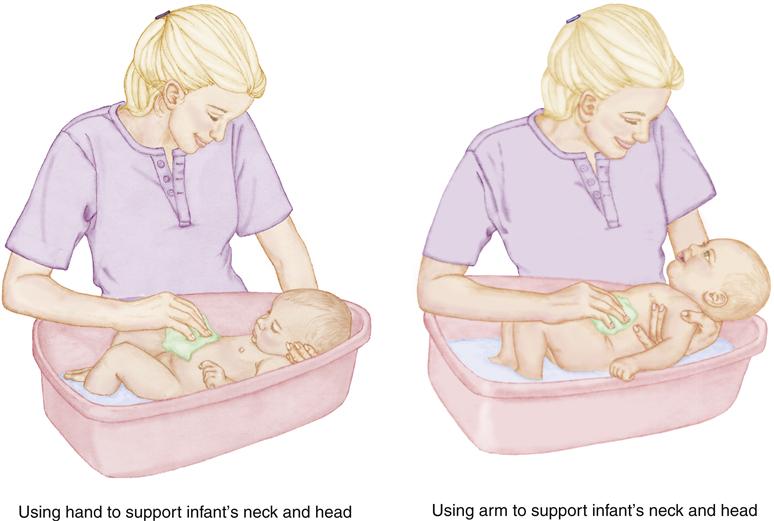

The nurse can use bath time to facilitate parent interaction with their infant. During the bath, the nurse demonstrates for the parents how to hold the infant securely and how to bathe the infant so that bath time is a positive experience for parents and children.

Strict observance of safety principles when bathing an infant or child can prevent falls, burns, or water aspiration. When bathing an infant or a child in the hospital setting, the nurse takes the opportunity to note any problems, such as altered skin integrity, surgical incisions, loss of sensation, abnormal skin color, bruising, paralysis, or any other condition that might warrant special consideration. Newborn infants can be immersed in water after the umbilical stump and circumcision sites (if applicable) have healed. The temperature of the bath water should not exceed 37.7° C (100° F)—that is, warm but not hot to the touch. If a bath thermometer is available, it should be used to check the temperature of the water. Otherwise, a temperature that is comfortable when tested on the inside of your wrist or elbow is appropriate.

Before bathing any child, assess the family’s preferences and home practices. Factors to consider include the time of day usually set aside for the bath, bathing rituals, special equipment, any product allergies, and the type of bath preferred. This time is also used to determine the amount of assistance needed by the child and the family and to address any learning needs related to hygiene. Because bathing is one of the areas over which parents might be allowed to retain control when a child is hospitalized, it is important to allow them to make as many decisions as possible. Decision making also allows parents to maintain a part of the home routine with their hospitalized child.

An infant who cannot sit unaided can be given either a sponge bath or a bath in an infant tub. The infant’s body and head are supported at all times during the bath (Figure 37-3). Older infants and toddlers can be bathed in either an infant tub or a regular bathtub. Infants and small children are never left unattended in the bath. Older children can take showers if facilities are available. The nurse should use judgment in deciding how much supervision an older child needs while bathing. Privacy for the school-age child and adolescent is extremely important.

Special Considerations

Bed baths are frequently used for hospitalized infants and children. When bathing a newborn or young infant, soap is not necessary. In fact, soap can be too drying to the skin if used frequently. If soap is necessary or desired by the parent, a gentle, non-alkaline soap should be used.

To prevent chilling when giving a sponge bath, be sure to keep the child covered with a cotton blanket. The entire body except for the body part being washed or rinsed is covered. The bath begins with the face, and the diaper area is cleaned last. If eye discharge is present, the nurse uses a clean, wet cotton ball for each eye, and cleans from the inner canthus outward. Use a clean cotton ball for each eye. The outer ears can be cleaned with a wet face cloth.

If bathing an infant, line a plastic infant tub with a towel to provide comfort, as well as traction to prevent slipping. To prevent accidental drowning should the infant slide down into the tub, fill the tub with no more than 3 inches of water.

When finished with the infant bath, the infant is wrapped in a dry towel or cotton blanket. Using the football hold and holding the infant over the tub, the nurse shampoos the infant’s scalp and hair (including the area over the fontanel) with baby shampoo. Talcum powder, baby powder, and cornstarch are not used in the diaper area. When these substances get moist, they provide a medium for organism growth. Talcum powder and cornstarch, if accidentally inhaled, can result in respiratory complications.

Older children may choose to take a bath or shower, if their condition allows. The nurse ensures that the child has adequate towels, soap, and toiletries. Either the parent, nurse, or other staff member should remain nearby to provide assistance upon request.

Should an older child or adolescent require a bed bath, adjust the room temperature to a comfortable setting, and draw the curtain around the bed. As with any bed bath, the nurse begins with the face and proceeds in a head-to-toe progression. Obtain fresh water when it is time to rinse the child. Drape the child adequately for privacy and warmth. To prevent chilling, dry each body section as it is rinsed. The bath can be followed with application of lotion or deodorant if desired. The nurse performs the same assessment as with any child and provides assistance as necessary.

Some bathing restrictions might apply to children with surgical incisions, skin traction, IV catheters, casts, urinary catheters, artificial airways, or feeding tubes. Children may be restricted or unable to tolerate certain position changes because of their underlying conditions or treatments. It is imperative to assess for these special needs before beginning the bath.

Documentation

Documentation includes the type of bath, child or parent participation, procedure tolerance, and any abnormal findings noted, such as bruising, rashes, or excoriation. Any lotions or other skin preparations used also should be recorded.

Parent Teaching

General principles of hygiene and safety might need to be reinforced with some parents. Instruction in the use of special bathing equipment, such as infant bathtubs, safety bars, or tub grips, should be included as part of discharge teaching and preparation. To prevent injury or accidental drowning, appropriate supervision of the child should be maintained at all times. Parents are taught to never leave an infant or a young child alone in the bath; the risk of drowning, even in small amounts of water, is high. Infant bath seats, which adhere to the floor of a regular bathtub by suction cups, are unsafe and should not be used because infants can slip out the sides or the seats can tip over.

Oral Hygiene

To remove excess food and bacteria, the nurse wipes an infant’s gums gently with a wet cloth after each feeding. After teeth erupt, a soft, damp cloth; a piece of gauze; or a child’s soft toothbrush can be used to clean the mouth and teeth after each feeding and before bed. Until the parent is certain that the child can perform oral care correctly and independently, young children are supervised and assisted if needed. Even then, reminders to brush might be necessary.

Children frequently need reminders to brush their teeth. Toothbrushing should be done at least twice daily with a child’s soft toothbrush and a small (pea-size) amount of toothpaste. Children may ingest excessive amounts of fluoride if they are allowed to use large amounts of toothpaste or if they eat the toothpaste (CDC, 2011). Using the recommended amount of toothpaste and encouraging the child not to swallow the toothpaste will prevent fluorosis (brown spots on the teeth caused by too much fluoride).

Flossing is useful for cleaning between teeth and maintaining healthy gums. The child should begin to floss when all the primary teeth are in or when the child’s molars begin to touch.

Immunosuppressed children, in particular, need excellent oral hygiene. Soft toothbrushes, sponge-covered Toothettes, or moistened gauze sponges can be used for dental care in the child who is at risk for gingival bleeding (see Chapter 48).

Discharge teaching in the area of oral hygiene is important and yet often forgotten. Many parents do not realize that an infant’s gums and teeth need to be cleaned. Children should have their first visit to a dentist by the time the first teeth erupt and no later than age 2½ years. Thereafter they should be seen on a regular basis (every 6 months) for services that include checkups, professional cleaning, and fluoride application.

The risk of dental caries increases if formula, milk, or other liquids remain in a child’s mouth overnight. Allowing an infant to fall asleep with a bottle containing one of these liquids can cause a condition known as bottle-mouth syndrome, which results in severely decayed primary teeth. Parents are instructed not to put a child to bed with a bottle of formula, juice, or sweetened liquid. If the child will not fall asleep without a bottle, advise the parent to use water only.

Good nutrition influences dental health. Teaching about oral hygiene often provides an opportunity to educate the child and family about proper nutrition and general health maintenance.

Feeding

Mealtimes can be difficult for the hospitalized child. Changes in routine, diet, and surroundings, as well as dietary restrictions and illness, affect the child’s ability and desire to eat. Refusing to eat might also be the way a child attempts to have some control.

The nurse assesses the child’s preferences and dislikes on admission and before ordering meals. Mealtime rituals and routines, as well as cultural food variations are noted. Serving favorite and preferred foods and offering nutritious snacks can ensure appropriate caloric and nutrient intake.

The type and form of food chosen should be appropriate to the child’s age and developmental level. (See Chapters 6 through 9 for a discussion of food types appropriate for each age-group.) When planning meals, the nurse must consider whether the child has any special needs or required restrictions. For example, an infant with gastric reflux may need formula that is thickened with rice cereal to prevent emesis, and an edematous child will likely be placed on a “no added salt” diet.

Feeding a hospitalized infant seldom differs from feeding an infant at home. Types of foods, feeding schedules, and routines should mimic home schedules and routines when possible. If the infant’s bottle or nipple brand is not available in the hospital, ask the parents to bring what the infant uses at home. Encourage parents to be present at mealtimes and feed their children if indicated. Feeding reinforces the special bond that develops between child and parent.

Nurses facilitate breastfeeding for infants by providing a private, quiet, and relaxed location so mother and infant feel comfortable and not rushed. If the mother is pumping breast milk for use when she is absent, the nurse meticulously follows hospital policy for labeling, storing, and administering pumped breast milk to the infant.

Unless medically contraindicated, infants should be held during feedings. Because of the risk of aspiration, bottles should never be propped; a pillow or rolled blanket must not be positioned next to an infant’s mouth. Frequent burping during and after feedings can reduce the incidence of regurgitation. To burp the infant, the nurse can use the upright hold and gently pats or rubs the infant’s back, or seat the infant on the nurse’s knees with a hand supporting the infant’s chin. After feeding, the infant can be positioned on the right side to facilitate the flow of the feeding toward the lower end of the stomach and allow any swallowed air to rise into the esophagus. However, if the nurse is placing an infant in the crib for sleep, the infant must be positioned supine, lying on his or her back. The supine position for sleeping infants has been shown to decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008).

Toddlers and preschoolers often use food as a source of control. They might exhibit “food jags,” during which they will eat only one or two items for a period of several days. They enjoy finger foods but are learning to use spoons or forks fairly competently. Colorful plates and cups may encourage a reluctant child to eat. Parents are encouraged to bring the child’s own cups or utensils from home to simulate usual mealtime routines as closely as possible.

For young children, the nurse cuts foods into pieces appropriate in size and texture to decrease the risk of aspiration. Foods to avoid include hot dogs, popcorn, peanuts, and grapes, because if aspirated, these can occlude the airway. Young children must be supervised when eating. They are also secured at a table, in a highchair, or in bed using an overbed table during meals. “Roaming” while eating increases the risk of food aspiration and should be avoided. Children are prompted to feed themselves independently as much as possible. Mealtime is limited to 15 to 20 minutes and discontinued if the child is playing with and not eating the food.

Older children and adolescents seldom have difficulty expressing their dietary preferences. Difficulty may arise, however, when children this age are placed on a restricted or special diet. For example, the diabetic child often has difficulty staying on a restricted diet in the face of peer pressure. The nurse needs to provide support and clear limits to ensure cooperation. Referral to a dietitian may be necessary to help the child make appropriate food choices.

Special Considerations

Keeping accurate intake and output (I&O) measurements may be necessary for many hospitalized children. The nurse measures and records all intake; oral, enteral, and parenteral. All output, including output from urine and stool; drainage from tubes, stomas, or fistulas; and emesis, is also measured and recorded. When measuring urinary output for a child in diapers, weigh each wet diaper and subtract the weight of a dry diaper of the same size. One gram of weight equals approximately 1 mL of urine output.

Documentation

Documenting the child’s nutritional intake assists in determining the child’s overall health. The nurse records food intake and preferences, as well as observations about the child’s appetite and eating patterns. Older children and adolescents are assessed for any abnormal eating patterns, because eating disorders are more prevalent in these age-groups.

Parent Teaching

Educating parents regarding feeding, special diets, and the nutritional needs of children is extremely important. The nurse should carefully instruct parents about how to manage any food or fluid restrictions, or special diets. A child with type 1 diabetes mellitus (see Chapter 51) or celiac disease (see Chapter 43) is at risk for injury if the prescribed diet is not closely followed.

Vital Signs

An underlying principle for obtaining vital signs in a child is to obtain the vital signs when the child is quiet, if at all possible. Sometimes this involves measuring the pulse and respirations when the child is asleep. If this timing is not possible, note any activity that affects accurate measurement (e.g., crying, playing).

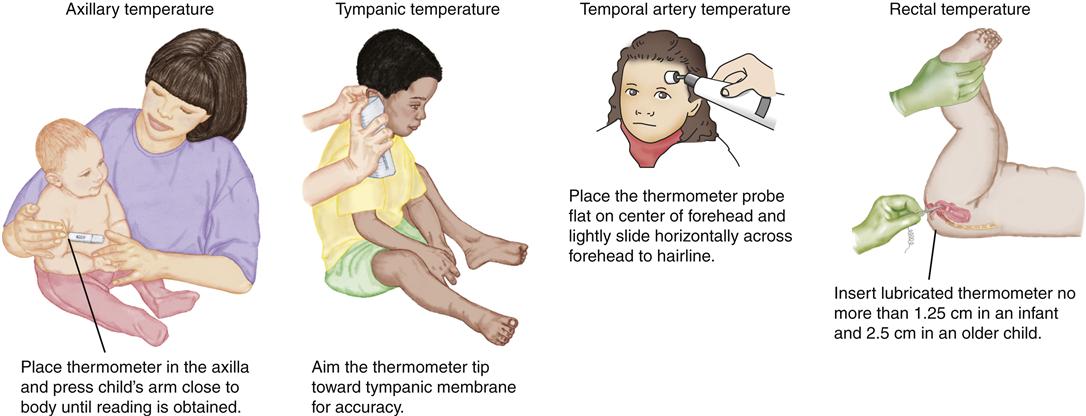

Measuring Temperature

Temperature is an objective indicator of illness, and measuring temperature is an integral part of assessing children. Oral, rectal, axillary, temporal artery (infrared), and tympanic temperature readings are often obtained using different types of electronic, digital thermometers. Beginning in 2001 and reaffirmed in 2007, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that thermometers containing mercury not be used for children in hospital or home settings because of toxicity risks (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007; Goldman, Shannon, & Committee on Environmental Health, 2001). Whatever temperature measurement method is chosen, the child’s temperature should be measured at the same site and with the same device to maintain consistency and allow reliable comparison and tracking of temperatures over time. (See Table 33-1 Chapter 33 for normal temperatures in children.)

Digital thermometers, which are most often run on batteries, measure the temperature quickly (usually in less than 30 seconds). To prevent cross contamination, a child may have a single thermometer kept in the hospital room. If an electronic thermometer is used for multiple patients, either use a new, disposable probe cover for each patient or cleanse the probe between patients in accordance with manufacturer guidelines.

There is considerable variation in the types of thermometers used to measure the temperature of a hospitalized child. Factors to consider when selecting the route to use for obtaining a temperature reading include the child’s age and ability to cooperate with the procedure, acuity of the illness, environmental factors (room conditions, food/fluid consumption), and equipment availability. For all devices used to measure temperature by any route, the accuracy of the temperature reading is dependent on correct use of the equipment; the probe must be in the correct position and held steadily in place for the required period of time (Davie & Amoore, 2010). For infants and children who are unable to properly hold an oral thermometer in their mouth, axillary, temporal artery, or tympanic thermometers are used (Figure 37-4). Rectal temperatures are more accurate in measuring core body temperature, particularly in infants (Paes, Vermeulen, Brohet, et al., 2010). However, inserting a thermometer into a child’s rectum is an invasive procedure and may be contraindicated for children at risk for anal or rectal injury, infection, or bleeding (El-Radhi & Patel, 2007). For this reason, many hospital units have policies that specify when a pediatric patient should have a rectal temperature measurement.

The advantage to temporal artery and tympanic temperature measurements is that they are obtained quickly, usually within a few seconds, and cause minimal discomfort to the child. Research has shown inconsistencies when comparing tympanic temperature measurement with axillary measurement (Carbone, Flanagan, Gibbons, et al., 2010; Devrim, Kara, Ceyhan, et al., 2007). A temporal artery temperature reading is considered to be nearly the same as the rectal (core) temperature and approximately 0.4° C (0.8° F) higher than an oral temperature (Exergen Corporation, 2005). However, the accuracy of temporal artery temperatures is still being evaluated; studies have indicated mixed results when comparing temporal artery measurements to temperature measurements via rectal and other routes (Bahr, Senica, Gingras, et al., 2010; Holzhauer, Reith, Sawin, et al., 2009).

Axillary temperatures are appropriate for infants and children younger than 4 to 6 years or any child who cannot safely have or hold an oral thermometer in the mouth. Axillary temperatures are approximately 0.6° C (1° F) lower than the body’s core temperature. For an accurate reading, the thermometer is held in the child’s axilla for a few minutes. To help the child remain still, consider holding him or her on your lap and reading a story.

Temperatures are measured orally in most children ages 6 years and older, including adolescents. Keeping a thermometer in the correct location in the mouth can be a challenge for any child. The child is instructed to keep the mouth closed, with lips in a “kiss” position, and to not bite the thermometer. Intake of foods and liquids should be avoided for 30 minutes before the oral temperature measurement. Inaccurate oral temperatures may occur because of oral intake, oxygen administration, nebulized treatments, or crying. Oral temperature measurement should not be used in any child who has had oral or tonsillar surgery or in whom epiglottitis is suspected (see Chapter 45).

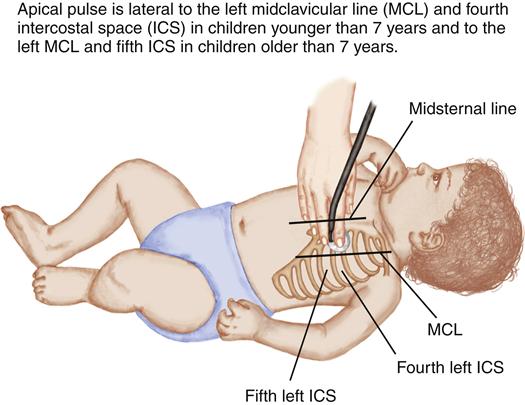

Measuring Pulse

Apical pulse rate measurements (Figure 37-5) are recommended for infants and children younger than 2 years of age and in any child who has an irregular heart rate or known congenital heart disease. It is best to auscultate the apical pulse when the child is quiet, counting for 1 full minute. The apical heart rate must be determined before administering certain medications, such as digoxin.

Radial pulse measurements are appropriate for children older than 2 years of age (see Table 33-1 for normal pulse measurements).

Evaluating Respirations

Infants often have irregular respiratory rates that change with stimulation, crying, and feeding. First, observe the pattern of inspiration and expiration to determine any irregular rhythm. Next, with an infant or young child who is quiet and at rest, measure the respiratory rate by auscultating for 1 full minute. For older children, either observe chest movement or auscultate respirations to obtain the rate (see Table 33-1 for normal respiratory rate measurements).

Measuring Blood Pressure

The blood pressure (BP) of a well child is generally assessed just once per year during routine physical examination. For the hospitalized child, BP readings are obtained on admission and then every 8 to 12 hours. If abnormalities are detected or the child’s condition is unstable, BP checks are done more frequently. When interpreting BP results, a child’s age, gender, and height must be considered (see Table 33-1 for normal values). The right arm is the standard site for routine BP measurement (Schell, 2006).

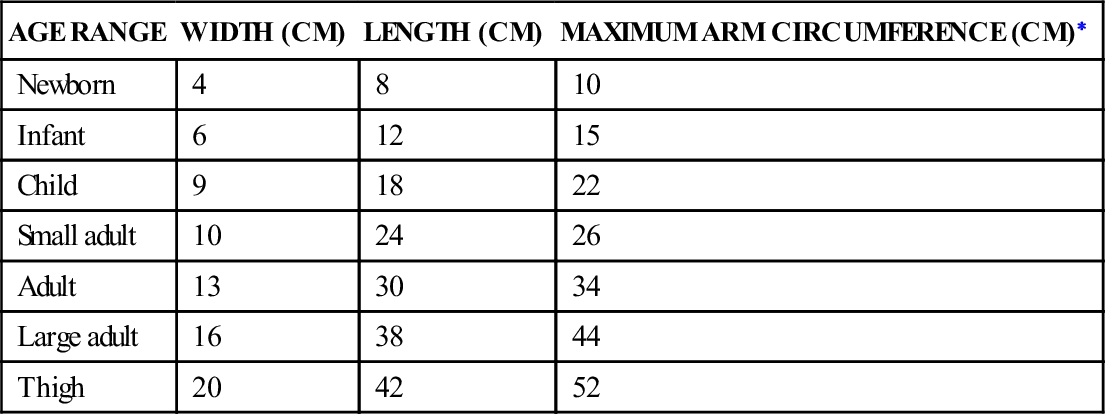

Choosing the appropriate cuff size is required if accurate BP readings are to be obtained. A cuff that is too small may cause a BP reading to be falsely high, and a cuff that is too large may result in a falsely low reading. Recommendations for how to choose an appropriate cuff size vary, but the following is a suggested procedure (Pickering, Hall, Appel, et al., 2005):

• Find the midpoint of the right upper arm between the shoulder (acromion) and the elbow (olecranon).

• Measure the BP with the arm at heart level after the child has been at rest for 3 to 5 minutes.

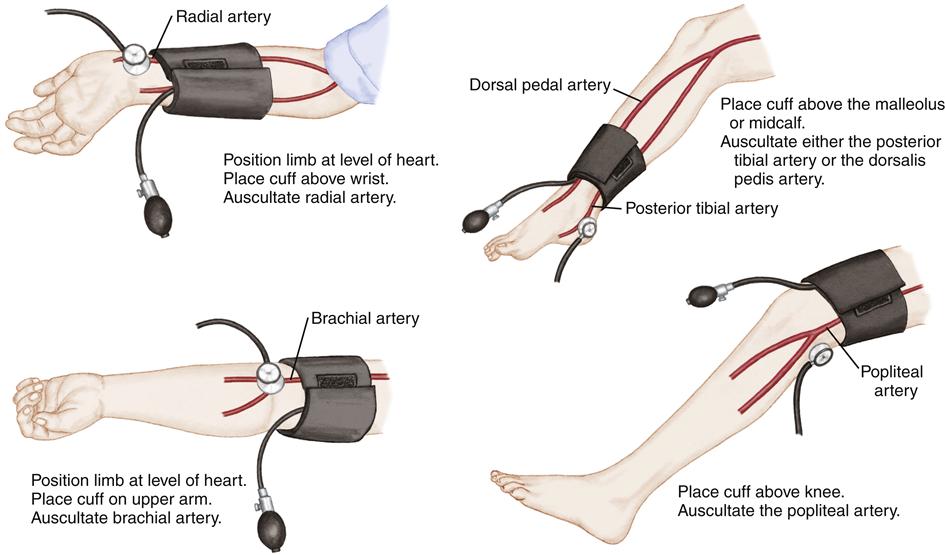

For children, BP can be measured in the upper arm, lower arm, thigh, calf, or ankle (Figure 37-6). If using a different site than the arm for BP measurement, the bladder should cover 40% of the circumference of the site used. Commercially designated BP cuffs are standardized widths, so select the closest standard width to the 40% circumference measurement. Table 37-1 illustrates average bladder widths of commercial BP cuffs.

TABLE 37-1

RECOMMENDED DIMENSIONS FOR BLOOD PRESSURE CUFF BLADDERS

| AGE RANGE | WIDTH (CM) | LENGTH (CM) | MAXIMUM ARM CIRCUMFERENCE (CM)∗ |

| Newborn | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| Infant | 6 | 12 | 15 |

| Child | 9 | 18 | 22 |

| Small adult | 10 | 24 | 26 |

| Adult | 13 | 30 | 34 |

| Large adult | 16 | 38 | 44 |

| Thigh | 20 | 42 | 52 |

∗Calculated so that the largest arm would still allow the bladder to encircle arm by at least 80%.

From National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. (2004). The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 114(2), 557.

To ensure consistency, take measurements in the same limb, in the same place, and with the child in the same position. BP measurements can differ depending on the site used, so the site must be documented (see http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/child_tbl.pdf for normal results).

The National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (2004) recommends auscultated BP measurements as the standard for children, and tables listing normal values are based on this method. For children, the systolic BP is determined by the onset of the first Korotkoff “tapping” sound, and the diastolic reading is the number at which the Korotkoff sound disappears. The systolic BP sometimes can be heard down to a measurement of zero. In this case, the BP measurement should be repeated with less pressure on the stethoscope. If a reading near zero is still obtained, the number when the Korotkoff sound muffles can be recorded as the diastolic BP (National High Blood Pressure Education Program, 2004).

Mercury sphygmomanometers are considered the “gold standard” but are rarely used because of mercury toxicity concerns. Aneroid sphygmomanometers are the substitute, although calibration is needed and accuracy is a concern (Schell, 2006). Automated, electronic devices are now frequently used because they make obtaining BP readings in children easier (Pickering et al., 2005). These oscillometric devices detect the mean arterial pressure, and then an algorithm is used to indirectly determine the systolic and diastolic BP values (Schell, 2006). Each type of device functions differently, so it is critical that the manufacturer’s guidelines be closely followed to ensure accuracy. If the BP result is low or elevated when taken electronically, retake the BP using auscultation.

Documenting Vital Sign Measurement

The nurse documents all vital signs in the child’s paper or electronic medical record; the measurement result, the method used to measure each vital sign, the site where each measurement was obtained, and any action taken is included. It is essential that the nurse reports, as well as documents, any abnormal findings or findings that are significantly different from the individual child’s baseline.

Preparing the Child and Family

The child and family are informed about the purpose of obtaining vital sign measurements. Children should be allowed to examine or handle the equipment while the nurse explains how it is used. Many children have toy medical instruments at home and may be familiar with the concept of taking vital signs.

Parent Teaching

Some parents may need to learn how to take the child’s temperature at home. The nurse demonstrates how to take the child’s temperature, and then observes the parent performing the procedure. It is important to ensure that the parent is comfortable with the procedure and is able to read the thermometer accurately.

Some parents may need to be taught how to correctly determine their child’s heart rate and respiratory rate, as well as the acceptable range for their child. Special instructions relating to when parents should notify the physician may need to be provided for children who are taking certain medications, such as digoxin.

If the child’s condition requires home BP monitoring, parents are taught to perform the procedure. The nurse provides

information about the size of the BP cuff needed and ensures that the parents can read the dial accurately. Methods to involve the child in the procedure are discussed. For example, parents might make a smaller BP cuff for the child’s favorite doll or stuffed animal.

Special Considerations: Cardiorespiratory Monitors

Some children need cardiorespiratory monitoring so that heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and temperature can be continuously measured. Children who are acutely ill or who are undergoing procedures might be placed on a monitor to help health care providers detect subtle changes in the child’s condition.

The procedure and indications for attaching a child to a cardiorespiratory monitor are no different from those for an adult. Monitors sound an alarm to warn of changes in the child’s cardiorespiratory status. In accordance with the child’s age, alarm parameters for each measurement are often preset based on hospital policies and physician orders. It is important that the nurse verify settings and test that the monitor is functioning correctly. False alarms can occur. Whenever a monitor alarm sounds, the nurse must first look at the child and perform an assessment, and then intervene if indicated. A flat line on the electrocardiogram (ECG) does not always signal a cardiac arrest. It may be nothing but a loose monitor lead. Check the manufacturer’s recommendations for attaching leads and monitoring selected vital signs.

Fever-Reducing Measures

The body’s internal thermostat, the hypothalamus, attempts to keep the body’s temperature between 36° C and 38° C (96.8° F and 100.4° F). This regulation is done through a complex series of interactions that result in heat gain or loss. The body’s mechanisms for conserving or producing heat are vasoconstriction and shivering. Heat is lost through radiation, conduction, convection, and evaporation.

Description of Fever

Fever is defined as a body temperature greater than 38° C (100.4° F) rectally or 37.5° C (99.5° F) orally that results from an insult or disease during which the body’s set point temperature rises to a higher-than-normal level. After the cause of the fever is removed, the body resets its set point at the normal level.

The body’s attempt to defend itself against illness is manifested by fever, which is triggered by endogenous pyrogens produced during the inflammatory response. Because research studies have not conclusively demonstrated whether fever is beneficial or detrimental, practitioners vary in their approach to managing fevers caused by infections. Mild degrees of fever may or may not require intervention, depending on the underlying cause and the child’s response. Most fevers are brief and benign and resolve when the underlying infection resolves. Children with chronic cardiac or respiratory disease, those with neurologic disease, and those prone to febrile seizures should be treated for fever. Children with fevers of 40° C (104° F) or higher also should be treated.

Fever is uncomfortable, and children may become irritable. For every 1° C of temperature elevation, the body’s metabolic rate increases 10% to 12%, resulting in increased insensible fluid loss, increased oxygen consumption, and increased stress on the cardiovascular system (Ward & Lentzsch-Parcells, 2009). Regardless of the fever’s cause, the child’s comfort is the primary reason for treating a fever in a normally healthy child.

Medications and Environmental Management

Treatment can consist of environmental measures, antipyretics, or a combination of interventions. Dressing the child appropriately (neither overdressed nor underdressed), providing adequate fluids, monitoring for signs of dehydration, and administering an appropriate antipyretic all are approaches to fever management. Studies have shown that the use of tepid sponging to reduce a fever can actual cause shivering and increase temperature as well as increased discomfort for the child (Axelrod, 2000; National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007).

Fevers in children are treated effectively with antipyretics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen (Perrott, Piira, Goodenough, et al., 2004). Aspirin is not used to treat fever in children because of its association with Reye syndrome and viral illnesses (influenza and varicella).

Children with elevated temperatures often have a loss of appetite. Dehydration can occur from decreased oral intake and increased insensible water loss through the lungs and skin. To provide for adequate hydration, offer the child oral fluids frequently. For those who refuse to ingest oral fluids or are unable to take in an adequate volume, evaluate the need for IV fluids.

To maintain body temperature and reduce heat loss, some infants are placed in radiant warmers or incubators (Isolettes). These microprocessor-based, servo-controlled temperature systems set the correct heating level by constantly monitoring the infant’s temperature using a skin probe and the air temperature. Infants who are being cared for in these heating units must be carefully monitored, because accidental dislodgment of the skin probe can occur, and excessive heating may result. Also, insensible water loss is greatly increased for infants in these units, and this must be considered when calculating fluid replacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree