Chapter 24

Prevention of Workplace Violence

L. Jean Henry and Gregory O. Ginn

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

Nursing is a challenging profession. Recent violent incidents in hospitals and care facilities have pushed the issue of workplace violence into the forefront of concerns among nursing communities and agencies charged with ensuring staff and patient safety. The health care industry is the site of more violence than any other industry, and nurses are victimized twice as often as other health care workers. Although the number of homicides in the health care industry is rather small, 48% of all nonfatal injuries from occupational assaults and violent acts in 2000 occurred in health care and social services (Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 2004, p. 5). To add to the gravity of the situation, most researchers agree that violence against nurses is significantly underreported.

Nurses are harmed by workplace violence. A systematic review of the literature on the effects of violence toward nurses reported the predominant responses to be anger, fear or anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, guilt, self-blame, and shame (Hogh & Viitasara, 2005). One researcher reported that physical and psychological aggression experienced by nurses was related to job dissatisfaction, turnover intention, physical symptoms, injuries, and exposure to contagious disease directly and/or indirectly through their emotional strain (irritation, anxiety, and depression) (Needham et al., 2005).

Violence in hospitals is caused by a combination of internal and external factors. External conditions include a society where violence is prevalent and the fact that many health care facilities are located in inner cities where crime rates are higher than average. Internal factors include inadequate staffing levels, larger numbers of dangerous patients, poor security for drugs and money, staff members working alone, poorly lit facilities, and unsecured, continuous access to health care facilities (OSHA, 2004).

Further, the very nature of the jobs that nurses perform places them at high risk for workplace violence, and circumstances inherent in health care work increase workers’ susceptibility to homicide or assault. Nurses often deal with people who are in pain, emotionally disturbed, or cognitively impaired; and often their families are experiencing strong emotions brought on by grief, catastrophic injuries, criminal victimization, or severe psychiatric disturbances. Staffs in nursing home/long-term care facilities, intensive care, psychiatric/behavioral or emergency departments, and geriatric facilities appear to be the most at risk. In addition, nurses are frequently confronted with situations that cause them moral distress. As professionals, nurses are engaged in a moral endeavor and thus confront many challenges in making the right decision and taking the right action. When nurses cannot do what they think is right, they experience moral distress that leaves a moral residue (Corley, 2002). The resultant stress can generate aggressive behaviors. Thus for a number of reasons, violence in the workplace is a particular concern for nurses.

Policies to prevent workplace violence can make a difference. Research has demonstrated that a stronger violence prevention climate (i.e., good prevention practices/response and low tolerance or incentives for unsafe practices) was related to less frequent violence and psychological aggression incidents experienced by nurses (Yang, 2009). Results of multiple regression analyses, controlling for appropriate factors, indicated that the odds of physical assault decreased for having a zero-tolerance policy and having policies regarding types of prohibited violent behaviors (Nachreiner et al., 2005). Reporting must be encouraged and staff asked to contribute to the development of efficient programs, thus leading to a sense of empowerment (Lanza et al., 2011). Therefore the issue is to convince organizations that (1) they can effectively institute a public health objective such as workplace violence prevention, and (2) the attainment of broader organizational objectives such as acceptable operational and financial performance is very much facilitated by successful workplace violence prevention programs (Ginn & Henry, 2002).

DEFINITIONS

Violence is narrowly defined as assault, battery, manslaughter, or homicide; and broadly defined as a range from verbal abuse, threats, and unwanted sexual advances to physical assault and homicide. Workplace violence may be conceptualized as a spectrum. One end is aggressive behavior such as verbal abuse, threats, harassment, and menacing behavior that may cause psychological harm. The other end is behavior such as assault, battery, manslaughter, or homicide that causes physical harm. It is important to define workplace violence as a spectrum because people often manifest aggressive psychological behavior as a precursor to violent physical behavior. By using a broad definition of violence, workplace violence prevention policies can respond to the psychological precursors of violence in order to preempt physical violence (Romano et al., 2011)

Sources of violence vary. One source of violence is from criminals with no other connection to the workplace, but who simply intend to commit a crime. A second source is from customers, clients, patients, or students; this is regarded as the most prevalent source of violence against nurses. A third source is from a current or former employee. A fourth source is from someone who is not employed at the workplace but has a personal relationship with an employee, such as a spouse or domestic partner (Rugala & Isaacs, 2004).

Risk factors for violence in health care organizations include working with volatile people, understaffing, long waits, poor environmental design, lack of training, inadequate security, substance abuse, poor lighting, and unrestricted access by the public. Working in hospitals may be dangerous because of the availability of drugs or money in the pharmacy area, the necessity of working evening or night shifts in high-crime areas, and the availability of furniture or medical equipment that could be used as weapons (OSHA, 2004, pp. 6-7).

REGULATORY BACKGROUND

Workplace violence has received increasing attention over the past three decades as a substantial contributor to occupational injury and death. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reported that homicide has become the second leading cause of occupational injury and death. Assaults represent a serious safety and health hazard for American workers, and violence against employees continues to increase (NIOSH, 2004).

Acknowledging that workplace violence was a pervasive and growing problem, the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 declared that employers had a general duty to provide safe and healthy working conditions. Through this act, NIOSH was charged with drafting and recommending occupational safety and health standards (OSHA, 2004).

OSHA followed up on the general duty requirement in 1989 with voluntary generic safety and health program management guidelines for all employers to use as a foundation for their safety and health programs. The guidelines were not regulations; however, under the OSHA act, employers face fines if an incident of workplace violence occurs. The agency made it clear that safety and health programs could include workplace violence prevention programs (OSHA, 2004).

In 1998, OSHA built on the 1989 generic workplace safety and health guidelines by announcing guidelines specifically targeted at the health care and social services industry. The new guidelines identify common risk factors and include policy recommendations and practical corrective methods to help prevent and mitigate the effects of workplace violence (OSHA, 2004). Clearly, managers of health care organizations have an ethical obligation to protect the safety of workers. Managers also have a general legal duty to prevent workplace violence. Given the significant economic costs of workplace violence and the potential legal liability, managers have a fiscal responsibility to prevent workplace violence.

NIOSH Recommendations

NIOSH is located within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NIOSH recognizes that workplace violence is a particular issue in the health care industry and recommends the following violence prevention strategies for employers: environmental designs, administrative controls, and behavior modifications. Environmental designs include signaling systems, alarm systems, monitoring systems, security devices, security escorts, lighting, and architectural and furniture modifications to improve worker safety. Administrative controls include (1) adequate staffing patterns to prevent personnel from working alone and to reduce waiting times, (2) controlled access, and (3) development of systems to alert security personnel when violence is threatened. Behavior modifications provide all workers with training in recognizing and managing assaults, resolving conflicts, and maintaining hazard awareness (NIOSH, 2002).

OSHA Guidelines

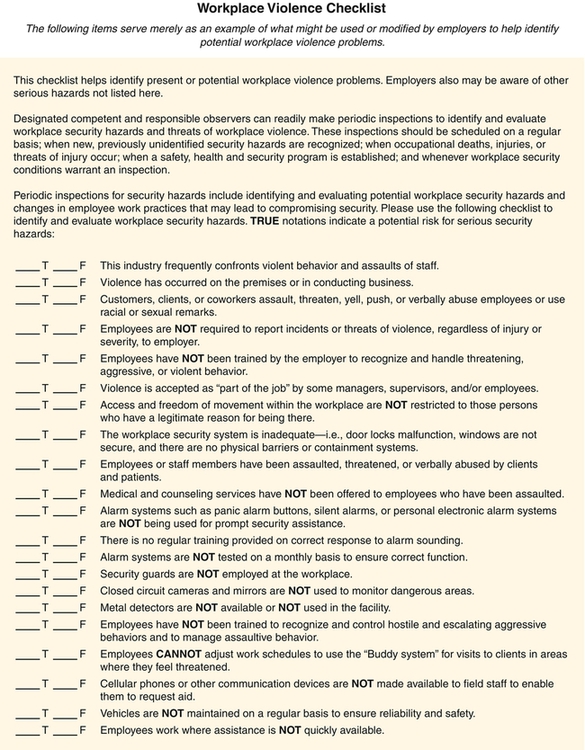

OSHA is an agency in the U.S. Department of Labor. OSHA suggests that all health care organizations have a violence prevention program. Ideally, violence prevention programs are available to all employees, track progress in reducing work-related assaults, reduce severity of injuries sustained by employees, decrease the threat to worker safety, and reflect the level and nature of threat faced by employees (OSHA, 2004). The main components in a violence prevention program are (1) a written plan, (2) worksite analysis, (3) hazard prevention and control, (4) safety and health training, and (5) recordkeeping and evaluation of program (Box 24-1 and Figure 24-1). Violence prevention written plans demonstrate management commitment by disseminating a policy that all types of violence will not be tolerated, ensures that no reprisals are taken against employees who report or experience workplace violence, encourages prompt reporting of all violent incidents, and establishes a plan for maintaining security in the workplace. Worksite analysis is a commonsense look at the workplace to find existing or potential hazards for workplace violence. Hazard prevention and control implement work practices to prevent and control identified hazards. Safety and health training makes all the staff aware of security hazards and how to protect themselves through established policies, procedures, and training. Recordkeeping and evaluation of programs provide the data to track progress in reducing work-related assaults.

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

Management Frameworks

Levels of workplace violence may vary depending on how much organizations focus on the root causes of workplace violence, such as individual characteristics and organizational environment factors (Hutchinson et al., 2010; O’Leary-Kelly et al., 1996). The implications for management of the threat of workplace violence vary depending somewhat on the source of violence. With regard to the first source of violence (criminals with no connection to the employer), a risk management approach is appropriate. With the second source of violence (patients), a total quality management approach may be effective. Concerning the third source of violence (current or former workers), good human resource management policies are essential. In dealing with the fourth source of violence (someone who has a personal relationship with an employee), employee assistance programs can be especially useful.

Risk management is an integrated effort across all disciplines and functional areas to protect the financial assets of an organization from loss by focusing on the prevention of problems that can lead to untoward events and lawsuits. A wide variety of measures are appropriate to prevent violence from criminal activity. Among these measures are posting security guards, restricting access to the general public, adequate lighting, escort services for those coming or going from parking lots, and installing alarm systems and systems to call for emergency assistance. If efforts at prevention fail, insurance is available to cover the specific costs of workplace violence (Law & Pettit, 2007). All of these actions can help prevent or mitigate losses from actions by criminals with no connection to the workplace.

Total quality management (TQM) comprises the general processes of setting standards, collecting information, assessing outcomes, and adjusting policies. TQM and risk management share the goals of eliminating problems, enhancing performance, and eliciting total organizational commitment. Under TQM, the organization uses all available resources, builds long-term relationships with both employees and patients, and remains open to ways in which processes can be improved to enhance the quality of operations. Teamwork is an integral part of TQM, along with a system for tracking violent incidents (Lanza et al., 2011; Smith, 2001; Wagner et al., 2001). All levels of the organization are expected to be involved in decision-making and employee training. Training topics should impart skills that support the strategic goals of the organization and could include prevalence, incidence, and warning signs of violence; policies and procedures; critical incident response; and availability of services associated with violence in the workplace (OSHA, 2004). Health care organizations can expand the team concept to include strategic partnerships and alliances (OSHA, 2004).

Essential to establishing a safe working environment is developing systems for reporting and documenting incidents of assaults and acts of aggression, as well as taking prompt action when a report is made. The reporting system should include the creation of special forms to report violent incidents, as well as the establishment of a hotline and confidential procedures for employees, to encourage timely and accurate reporting of all forms of violence (OSHA, 2004, pp. 21-24). The principles of TQM are manifested in OSHA’s guidelines for violence prevention programs in health care; Henry and Ginn (2002) illustrated and discussed this relationship in more depth.

Human Resource Management Policies

A comprehensive violence prevention policy and procedural manual should be developed to guide organizational violence prevention efforts. Violence prevention occurs on three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary refers to lowering the risk of occurrence; secondary refers to containing or limiting the violence; and tertiary refers to retrospective assistance and support to the injured (Hogh & Viitasara, 2005).

A number of management policy recommendations in the literature can be applied to the prevention of workplace violence. Organizations should be particularly careful regarding employees’ perceptions of procedural fairness concerning layoffs, performance, and conflict resolution. Explaining to employees how or why certain events, such as layoffs, have occurred will lessen the likelihood of workplace aggression. Further, organizations can train employees on how to handle situations of unfairness and how to create fair working environments. Organizations can implement a zero-tolerance policy toward aggression to lessen the possibility of work groups encouraging an individual to act aggressively (Beugre, 2005).

In the area of personnel, some suggest that organizations have policies to require thorough screening of applicants to weed out those who may have a propensity for violence. Such procedures may eliminate some violence from co-workers, because a history of violence is the best indicator of future violence (Corbo & Siewers, 2001). One possibility is to include screening for domestic violence in new employee screening (Anderson, 2002). Thorough employee screening and appropriate termination policies will, at the least, contribute to a legal defense that reasonable action to prevent violence has been taken.

In dealing with potential violence from co-workers, threat assessment and threat management are important concepts to consider. Threat assessment consists of the evaluation of the threat itself and an evaluation of the threatener. Health care managers must make some effort to determine whether the person making threats was serious about inflicting harm or just verbalizing frustration; however, this is not to diminish the seriousness of verbal assaults. Threat management refers to the course of action taken after conducting a threat assessment. Health care managers might want to investigate the person making threats and admonish, reprimand, counsel, or terminate the employee, as well as provide post-incident counseling for the victim of the threats (Rugala & Isaacs, 2004). Still another procedural approach is to circulate generalized information such as typical profiles of workplace killers (violent employees), characteristics of disgruntled employees, motivations for violent actions, and factors that contribute to the problem (Boxes 24-2 and 24-3).