Pressure ulcers and traumatic wound care

Preventing, staging, and treating wounds

Preventing, staging, and treating wounds

Pressure ulcer care

As their name implies, pressure ulcers result when pressure—applied with great force for a short period or with less force over a longer period—impairs circulation, depriving tissues of oxygen and other life-sustaining nutrients. This process damages skin and underlying structures. Untreated, the ischemic lesions that result can lead to serious infection.

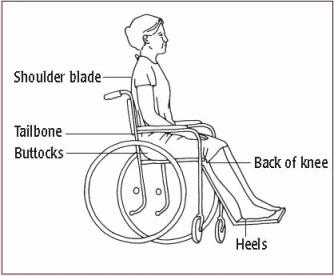

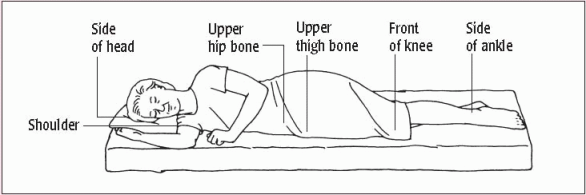

Most pressure ulcers develop over bony prominences, where friction and shearing force combine with pressure to break down skin and underlying tissues. Common sites include the sacrum, coccyx, ischial tuberosities, and greater trochanters. Other common sites include the skin over the ears, vertebrae, scapulae, elbows, knees, and heels in bedridden and relatively immobile patients. (See Pressure points: Common sites for ulcers.)

Successful treatment of pressure ulcers involves relieving pressure, restoring circulation and, if possible, resolving or managing related disorders. Typically, the effectiveness and duration of the treatment depend on the characteristics of the pressure ulcer. (See Staging pressure ulcers, pages 452 and 453.)

Ideally, prevention is the key to avoiding extensive therapy. Preventive measures include ensuring adequate nourishment and mobility to relieve pressure and promote circulation.

When a pressure ulcer develops despite preventive efforts, treatment includes methods to decrease pressure, such as frequent repositioning to shorten the duration of the pressure and the use of special equipment to reduce the intensity of the pressure. Treatment may also involve the use of special devices, such as beds, mattresses, mattress overlays, and chair cushions. (See Pressure reduction devices, page 454.) Other therapeutic measures include reducing risk factors and using topical treatments, wound cleaning, debridement, and moist dressings to support wound healing.

The nurse usually performs or coordinates treatments according to facility policy. The procedures described here address cleaning and dressing pressure ulcers. Always follow the “Standard Precautions” guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Equipment and preparation

Hypoallergenic tape or elastic netting ♦ piston-type irrigating system ♦ two pairs of gloves ♦ normal saline solution, as ordered ♦ sterile 4″ × 4″ gauze pads ♦ selected topical dressing (moist saline gauze, hydrocolloid, transparent, alginate, foam, or hydrogel) ♦ linensaver pads ♦ impervious plastic trash bag ♦ disposable wound-measuring device ♦ sterile cotton swabs ♦ optional: 21G needle and syringe, alcohol pad, pressure-reducing device, turning sheet

Assemble the equipment at the patient’s bedside. Cut the tape into strips for securing dressings. Loosen the lids on cleaning solutions and medications for easy removal. Make sure that the impervious plastic trash bag is within reach.

Implementation

♦ Before performing any dressing change, wash your hands and review the principles of standard precautions.

Cleaning the pressure ulcer

♦ Provide privacy and explain the procedure to the patient to alleviate his fears and promote cooperation.

♦ Position the patient in a way that maximizes his comfort while allowing easy access to the pressure ulcer site.

♦ Cover the bed linens with a linensaver pad to prevent soiling.

♦ Open the normal saline solution container and the piston syringe. Carefully pour normal saline solution into an irrigation container to avoid splashing. (The container may be clean or sterile, depending on facility policy.) Put the piston syringe into the opening provided in the irrigation container.

♦ Open the packages of supplies.

♦ Put on gloves to remove the old dressing and expose the pressure ulcer. Discard the soiled dressing in the impervious plastic trash bag to avoid contaminating the sterile field and spreading infection.

♦ Inspect the wound. Note the color, amount, and odor of drainage and necrotic debris. (See Tailoring wound care to wound color, page 455.) Measure the perimeter of the wound with the disposable wound-measuring device (a square, transparent card with concentric circles arranged in a bull’seye fashion and bordered with a straightedge ruler).

♦ Using the piston syringe, apply full force to irrigate the pressure ulcer to remove necrotic debris and help to decrease bacteria in the wound.

♦ Remove and discard the soiled gloves and put on a fresh pair.

♦ Insert a gloved finger or a sterile cotton swab into the wound to assess wound tunneling or undermining. Tunneling usually signals extension of the wound along fascial planes. Gauge the

depth of the tunnel by determining how far you can insert your finger or the cotton swab.

depth of the tunnel by determining how far you can insert your finger or the cotton swab.

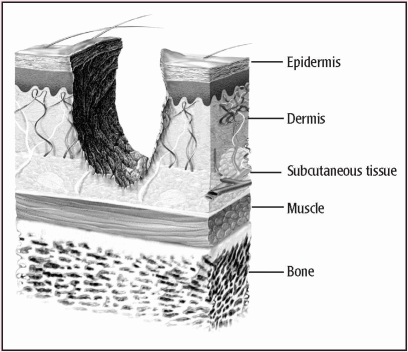

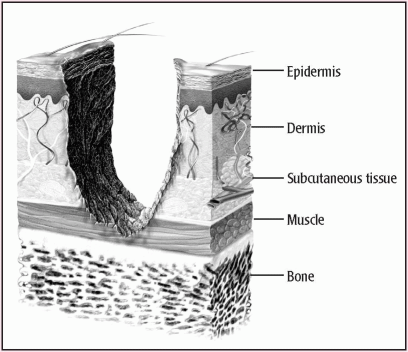

Staging pressure ulcers

The pressure ulcer staging system described here, used by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, reflects the anatomic depth of exposed tissue. Keep in mind that if the wound contains necrotic tissue, you won’t be able to determine the stage until you can see the wound base.

Suspected deep tissue injury

Deep tissue injury is characterized by a purple or maroon localized area of intact skin or a blood-filled blister caused by damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure or shear. The injury may be preceded by tissue that’s painful, firm, mushy, boggy, or warm or cool compared to adjacent tissue. Further, it may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones.

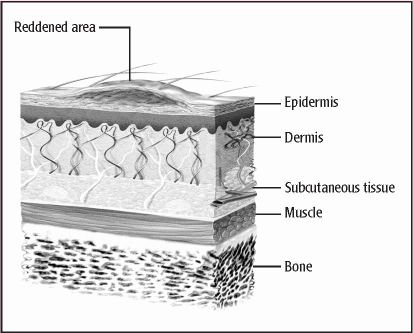

Stage I

A stage I pressure ulcer is characterized by intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area, usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching, but its color may differ from the surrounding area.

|

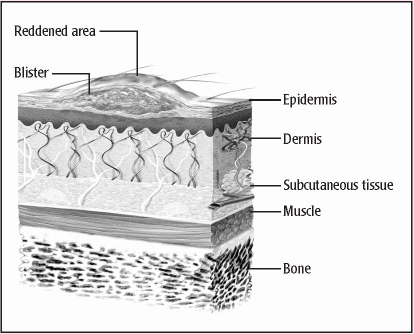

Stage II

A stage II pressure ulcer is characterized by partial-thickness loss of the dermis, presenting as a shallow, open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed without slough. It may also present as an intact or open serum-filled blister

|

Stage III

A stage III pressure ulcer is characterized by full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible, but bone, tendon, and muscle aren’t exposed. Slough may be present but doesn’t obscure the depth of tissue loss. Undermining and tunneling may be present. The depth of a stage III ulcer varies by anatomical location.

|

Stage IV

A stage IV pressure ulcer involves full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed. Undermining and tunneling are also common. The depth of a stage IV ulcer varies by anatomical location.

|

Unstageable

An unstageable ulcer is characterized by full-thickness tissue loss in which the base of the ulcer in the wound bed is covered by slough, eschar, or both. Until enough slough or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, can’t be determined.

Pressure reduction devices

The use of special pads, mattresses, and beds can help to relieve pressure when a patient is confined to one position for long periods.

Gel pads

Gel pads disperse pressure over a wide surface area.

Water mattress or pads

A wave effect provides even distribution of body weight.

Alternating-pressure air mattress

Alternating deflation and inflation of the mattress tubes changes the areas of pressure.

Foam mattress or pads

Foam areas, which must be at least 3″ (7.5 cm) thick, cushion skin and minimize pressure.

Low-air-loss beds

The surface of low-air-loss beds consists of inflated air cushions. Each section is adjusted to provide optimal pressure relief.

Air-fluidized beds

Air-fluidized beds contain beads that move under an airflow to support the patient, thus reducing shearing force and friction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access