Pregnancy-Related Complications

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Discuss the effects and management of hyperemesis gravidarum.

• Describe the development and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

Complications during pregnancy sometimes threaten the well-being of the expectant mother, her fetus, or both. The most common pregnancy-related complications are hemorrhagic conditions that occur in early pregnancy, hemorrhagic complications of the placenta in late pregnancy, hyperemesis gravidarum, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and blood incompatibilities between the mother and fetus.

Hemorrhagic Conditions of Early Pregnancy

The three most common causes of hemorrhage during the first half of pregnancy are abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and hydatidiform mole.

Abortion

Abortion is the loss of pregnancy before the fetus is viable, that is, before it is capable of living outside the uterus. The medical consensus today is that a fetus of less than 20 weeks of gestation or one weighing less than 500 g is not viable. Abortion may be either spontaneous or induced. Miscarriage is a term used by laypeople to denote an abortion that has occurred spontaneously as opposed to one that has been induced, and the term is becoming accepted by professionals as well. Elective termination of pregnancy, also called induced abortion, is described in Chapter 32. Spontaneous abortion denotes termination of a pregnancy without action taken by the woman or any other person.

Spontaneous Abortion

Determining the exact incidence of spontaneous abortion is difficult because many unrecognized losses occur in early pregnancy. The incidence of spontaneous abortion increases with parental age. The incidence is 12% for women younger than 20 years, rising to 26% for women older than 40 years. Increasing paternal age is also associated with rising spontaneous abortion rates, from 12% in men younger than 20 years to 20% in men older than 40 years. Most spontaneous abortions occur in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, with the rate declining rapidly thereafter. Fetal death occurs before the signs and symptoms appear (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al, 2010; Porter, Branch, & Scott, 2008).

The most common cause of spontaneous abortion is severe congenital abnormalities that are often incompatible with life. Chromosomal abnormalities account for about 50% to 60% of spontaneous abortions in the first trimester. Additional causes may include maternal infections and endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism or insulin-dependent diabetes. Still other women who have repeated early pregnancy losses appear to have immunologic factors that play a role in their higher-than-expected spontaneous abortion incidence. Anatomic defects of the uterus or cervix may contribute to pregnancy loss at any gestation (Cunningham et al., 2010).

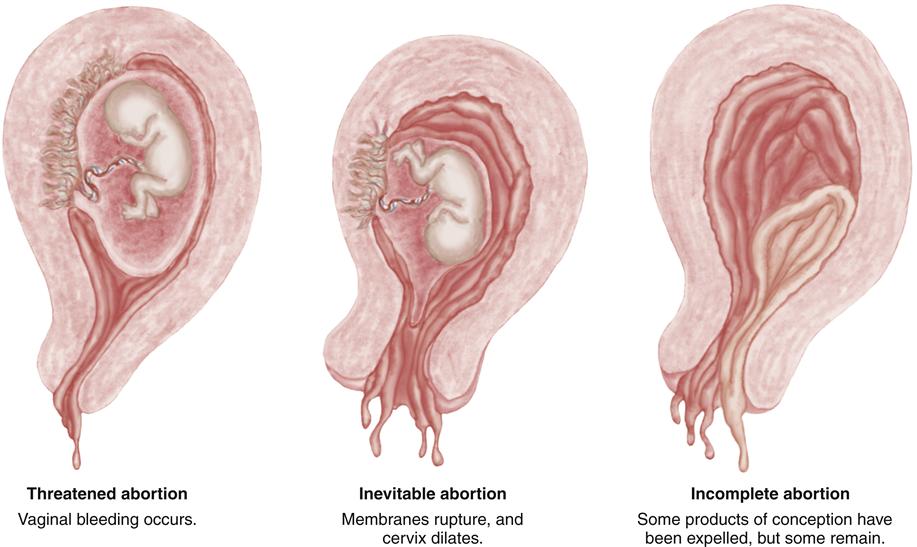

Spontaneous abortion is divided into six subgroups: threatened, inevitable, incomplete, complete, missed, and recurrent. Figure 25-1 illustrates threatened, inevitable, and incomplete abortion.

Threatened Abortion

Manifestations

The first sign of threatened abortion is vaginal bleeding. Up to 25% of all women experience “spotting,” or light bleeding, in early pregnancy, and about half of these pregnancies will not survive. Vaginal bleeding, which may be brief or last for weeks, may be followed by uterine cramping, persistent backache, or feelings of pelvic pressure. These added symptoms of pain and pressure are more likely to be associated with progression to loss of the pregnancy. When examined using a speculum, the cervix is closed. Laboratory tests show rising levels of beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG or possibly b-hCG or β-hCG), and the uterine size increases with embryonic growth if the pregnancy remains viable (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Therapeutic Management

Bleeding in the first half of pregnancy must be considered a threatened abortion, and women should be advised to notify their physician or nurse-midwife if they note vaginal bleeding. The nurse obtains a detailed history that includes length of gestation or time of last menstrual period and the onset, duration, and amount of vaginal bleeding. Accompanying discomfort, such as cramping, backache, abdominal pain, or pelvic pressure, is evaluated. Fever or uterine tenderness suggests infection.

Vaginal ultrasound is performed to determine whether a fetus is present and, if so, whether it is alive. Levels of beta-hCG may be done to determine if they are appropriate for the gestation and if they are rising as the fetus grows.

The woman may be advised to curtail sexual activity until bleeding has ceased. Bed rest or other restriction of physical activity has not been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of threatened abortion. The woman is instructed to count the number of perineal pads (peripads) used and to note the quantity and color of blood on the pads. She should also look for tissue passage. Drainage with a foul odor suggests infection.

The woman often wonders whether her actions may have contributed to the situation and is anxious about her own condition as well as that of the fetus. The nurse should offer accurate information and avoid false reassurance, because the woman may lose the fetus despite every precaution. In addition, later complications, such as preterm birth or low birth weight may occur, even if the pregnancy progresses.

Inevitable Abortion

Manifestations

Abortion is usually inevitable (i.e., it cannot be stopped) when the membranes rupture and the cervix dilates. Active bleeding that is heavier than that of threatened abortion is common.

Therapeutic Management

Natural expulsion of the uterine contents is common, and no further treatment may be needed. If tissue remains or if bleeding is excessive, the physician performs a dilation and vacuum curettage (D&C) to clean the uterine walls and remove remaining uterine contents while the woman is under intravenous (IV) sedation or anesthesia.

Incomplete Abortion

Manifestations

Incomplete abortion occurs when some but not all of the products of conception are expelled from the uterus. The major manifestations are active uterine bleeding and severe abdominal cramping. The cervix is open, and fetal and placental tissue is passed. All products of conception may have been expelled from the uterus but remain in the vagina because of their small size, often no larger than a Ping-Pong ball if the gestation is very early.

Therapeutic Management

Retained tissue prevents the uterus from contracting firmly, thus allowing profuse bleeding from uterine blood vessels. Initial treatment should focus on ensuring the woman’s cardiovascular stability. Blood is drawn for a type and screen, and an IV line is inserted for fluid replacement and drug administration. A later pregnancy and a larger amount of fetal tissue may require greater cervical dilation and evacuation (D&E) followed by vacuum or surgical curettage. This procedure may be followed by IV administration of oxytocin (Pitocin) or intramuscular (IM) administration of methylergonovine (Methergine) to contract the uterus and control bleeding.

Because of the danger of excessive bleeding, curettage may not be performed if the pregnancy has advanced beyond 14 weeks. In this case, oxytocin or prostaglandin is administered to stimulate uterine contractions until all products of conception (fetus, membranes, placenta, amniotic fluid) are expelled.

Complete Abortion

Manifestations

Complete abortion occurs when all products of conception are expelled from the uterus. Uterine contractions and bleeding abate, and the cervix closes after all products of conception are passed.

Therapeutic Management

Once complete abortion is confirmed, no additional intervention is required unless excessive bleeding or infection develops. The woman should be advised to rest and watch for further bleeding, pain, or fever. She should abstain from vaginal intercourse until after a follow-up visit with her health care provider. Contraception will be discussed at this visit if she wishes to avoid pregnancy.

Missed Abortion

Manifestations

Missed abortion occurs when the fetus dies during the first half of pregnancy but is retained in the uterus. When the fetus dies, the early symptoms of pregnancy (nausea, breast tenderness, urinary frequency) disappear. The uterus stops growing and often decreases in size, reflecting the absorption of amniotic fluid and fetal maceration, or discoloration and softening of tissues, and eventual disintegration of the fetus.

Therapeutic Management

In most cases, the pregnancy ends spontaneously after fetal death (Cunningham et al., 2010). If the fetus is not expelled, fetal death is confirmed by ultrasound examination. When fetal death is confirmed, the uterus may be evacuated by D&C. Prostaglandin E2 or misoprostol (Cytotec) may be necessary to induce contractions and empty the uterus during the second trimester.

Two major complications of missed abortion are infection and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). If there are signs of uterine infection, such as an elevated temperature, vaginal discharge with a foul odor, or abdominal pain, evacuation of the uterus is delayed until antibiotic therapy is initiated.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (Consumptive Coagulopathy)

DIC is a defect in coagulation that may occur if the fetus is retained for a prolonged period. Although DIC may occur with other pregnancy complications, such as abruptio placentae (p. 585) or hypertension (p. 590), the coagulation defects may occur in the absence of pregnancy.

With DIC, anticoagulation and procoagulation factors are activated simultaneously. DIC develops when the clotting factor thromboplastin is released into the maternal bloodstream as a result of placental bleeding and consequent clot formation. The circulating thromboplastin may activate widespread clotting in small vessels throughout the body. This process consumes, or “uses up,” other clotting factors such as fibrinogen and platelets. The condition is further complicated by activation of the fibrinolytic system to lyse, or destroy, clots. The result is a simultaneous decrease in clotting factors and increase in circulating anticoagulants, which leaves the circulating blood unable to clot. This situation allows bleeding to occur from any area, such as IV sites, incisions, or the gums or nose, as well as from expected sites such as the site of placental attachment during the postpartum period.

In DIC, fibrinogen and platelets are usually decreased, prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times may be prolonged, and fibrin degradation products, the most sensitive measurement, are increased. The D-dimer serum assay, which is normally negative, is a specific measurement of fibrin degradation activity that may be ordered.

The priority in treating DIC is delivery of the fetus and placenta to stop the production of thromboplastin, which is fueling the process. In addition, blood replacement products, such as whole blood, packed red blood cells, and cryoprecipitate, are administered to maintain the circulating volume and to transport oxygen to body cells.

Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion

Manifestations

Recurrent spontaneous abortion is sometimes referred to as habitual abortion; the current definition is three or more consecutive spontaneous abortions. The primary causes of recurrent abortion are believed to be genetic or chromosomal abnormalities or anomalies of the woman’s reproductive tract, such as bicornuate uterus that has two horns or incompetent cervix.

Additional causes include an inadequate luteal phase with insufficient secretion of progesterone and immunologic factors that involve increased sharing of human leukocyte antigens by the sperm and ovum of the man and woman who conceived. The theory is that because of this sharing, the woman’s immunologic system is not stimulated to produce blocking antibodies that protect the embryo from maternal immune cells or other damaging antibodies. Systemic diseases, such as lupus erythematosus and diabetes mellitus, have been implicated in recurrent abortions. Reproductive infections and some sexually transmitted diseases are also associated with recurrent abortions.

Therapeutic Management

The first step in managing recurrent spontaneous abortion is a thorough examination of the woman’s reproductive organs to determine whether anatomic defects, such as a bicornate uterus with two horns, are the cause. If her reproductive organs are normal, the woman is usually referred for genetic screening to identify genetic factors that would increase the possibility of recurrent abortions. Additional therapeutic management of recurrent pregnancy loss depends on the cause. For example, antimicrobials are prescribed for the woman with infection, or hormone-related drugs may be prescribed if imbalance preventing normal fetal implantation and support is found.

Recurrent spontaneous abortion may be caused by cervical incompetence, an anatomic defect that results in painless dilation of the cervix in the second trimester. In this instance, the cervix may be sutured to keep it from opening (i.e., cerclage). Sutures may be removed near term if vaginal delivery is expected, or they may be left in place if a cesarean birth is planned. Prophylactic antibiotics may be necessary if the woman is judged to be at high risk for infection. Preterm labor may still occur but, it is hoped, after the fetus is viable.

Nursing Considerations

Spontaneous abortion may be accompanied by various amounts of bleeding. Prevention or identification and treatment of hypovolemic shock (rapid pulse, lightheadedness, syncope, falling blood pressure) are the nursing priorities when a woman is bleeding heavily. The nurse should observe for tachycardia (often the earliest sign of hypovolemia), a falling blood pressure (late sign), pale skin and mucous membranes, confusion, restlessness, and cool and clammy skin. The nurse manages fluid and blood replacement as ordered.

Vaginal bleeding of any amount during pregnancy is frightening, and waiting and watching are difficult, although often the only reasonable treatment. Moreover, many families feel an acute sense of loss and grief with spontaneous abortion. Grief often includes feelings of guilt, which may be expressed as wondering if the woman could have done something to prevent the loss. Nurses may be able to help by emphasizing that most spontaneous abortions occur because of factors or abnormalities that could not be avoided.

Anger, disappointment, and sadness are commonly experienced emotions, although the intensity of the feelings may vary. For many women, the fetus has not yet taken on specific physical characteristics, but they grieve for their fantasies of the lost child. The woman or couple may want to express their sadness but may feel that family, friends, and often health personnel are uncomfortable or diminish their loss. Nurses may identify if their clinical facility offers options to dispose of fetal tissue and work to identify improvements (Limbo, Kobler, & Levang, 2010; Nansel, Doyle, Frederick, et al., 2005).

To recognize the meaning of the loss to each family, nurses must listen carefully to what the couple say and observe how the partners behave. Nurses must attempt to convey unconditional acceptance of the feelings expressed or demonstrated. The couple should be permitted to remain together as much as possible. Providing information and simple, brief explanations

of what has occurred and what will be done facilitates the family’s ability to grieve.

It is helpful for the family to realize that grief may last from 6 months to a year, or even longer. Family support, knowledge of the grief process, spiritual counselors, and the support of other bereaved couples may provide needed assistance during this time.

Ectopic Pregnancy

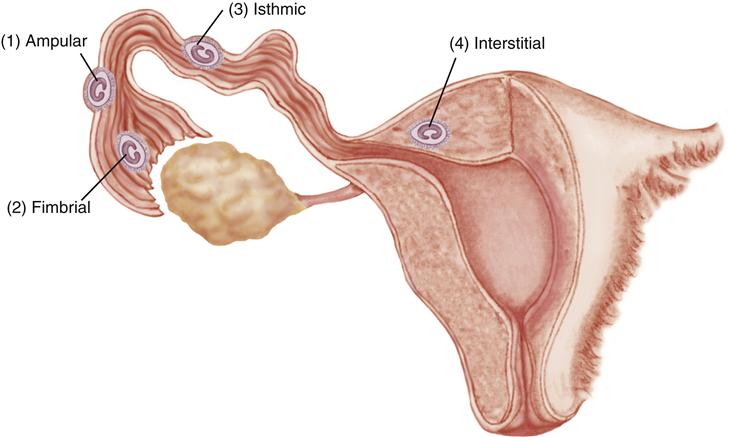

Ectopic pregnancy refers to implantation of a fertilized ovum in an area outside the uterine cavity. More than 95% of ectopic pregnancies are in the fallopian tube, usually the ampulla, or middle part of the tube. Figure 25-2 shows common sites of tubal implantation. Anything that slows the transport of the fertilized ovum through the tube or causes it to implant too early increases the risk that implantation will occur in the tube rather than the uterus.

Incidence and Etiology

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased dramatically throughout the world since 1970 from 4.5 per 1000 pregnancies to 19.7 per 1000 pregnancies. Ectopic pregnancy rates are higher in nonwhite women and older women. The highest rate is seen in nonwhite women older than 35 years (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2010c; Cunningham et al., 2010; Seeber & Barnhart, 2008). The rapid increase in incidence is attributed to the growing number of women of childbearing age who experience scarring of the fallopian tubes caused by pelvic infection, inflammation, or surgery. Pelvic infection or inflammation (pelvic inflammatory disease [PID]) is often the result of sexually transmitted diseases such as Chlamydia or Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Pelvic infection also may occur after induced abortion or childbirth. Women who require assisted reproductive techniques to conceive also have a greater risk, probably the result of the underlying pathology that caused infertility (Box 25-1).

Additional risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include:

Manifestations

Early signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy are:

More subtle signs and symptoms depend on the site of implantation. If implantation occurs in the distal end of the fallopian tube, which can accommodate a larger embryo, the woman may at first exhibit the usual early signs of pregnancy. Several weeks into the pregnancy, intermittent abdominal pain and small amounts of vaginal bleeding occur. These early manifestations are easily mistaken for those of threatened abortion. An embryo implanted in the tube may also die early and be reabsorbed by the body.

If implantation has occurred in the proximal end of the fallopian tube, rupture of the tube may occur within 2 to 3 weeks of the missed period. Symptoms include sudden, severe pain in one of the lower quadrants of the abdomen as the tube tears open and the embryo is expelled into the pelvic cavity. Pain is often accompanied by intraabdominal hemorrhage. Irritation of the diaphragm, manifested by shoulder or neck pain that is worse on inspiration, occurs in about half of women (Cunningham et al., 2010; Seeber & Barnhart, 2008). Signs of hypovolemic shock may develop with no or minimal external bleeding.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The combined use of transvaginal ultrasound examination (see Chapter 15) and determination of the beta-hCG level usually results in early detection of ectopic pregnancy. An abnormal pregnancy is suspected if beta-hCG is present but at lower levels than expected. If a gestational sac cannot be visualized when beta-hCG is present, a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy may be made with great accuracy. Visualization of an intrauterine pregnancy, however, does not absolutely rule out an ectopic pregnancy. A woman may have an intrauterine pregnancy and concurrently have an ectopic pregnancy.

The use of sensitive pregnancy tests, maternal serum progesterone levels, and high-resolution transvaginal ultrasound has largely eliminated invasive tests for ectopic pregnancy. Laparoscopy (examination of the peritoneal cavity by means of a laparoscope) occasionally may be necessary to diagnose rupture of an ectopic pregnancy. A characteristic bluish swelling within the tube is the most common finding.

Therapeutic Management

The management of tubal pregnancy depends on whether the tube is intact or ruptured. Medical management may allow preservation of the tube, thus improving the chance of future fertility. Medical management is most successful if the tube is intact, the pregnancy is early, the size of the pregnancy is less than 3.5 cm, and the fetus is not living. The cytotoxic drug methotrexate (a folic acid antagonist that interferes with cell reproduction) inhibits cell division in the embryo. Single-dose methotrexate therapy has shown a higher failure rate and two-dose or fixed multidose therapy is more often used. Laboratory evaluation of beta-hCG levels are repeated as needed to evaluate success of drug therapy. Surgical treatment may be needed if methotrexate treatment fails or if the woman shows a high suspicion of tubal rupture (ACOG, 2010c; Cunningham et al., 2010; Seeber & Barnhart, 2008).

Surgical management of a tubal pregnancy that is unruptured may involve a linear salpingostomy to salvage the tube for future pregnancies. The tube is opened with a fine linear incision, the products of conception are removed, and to reduce scarring, the tubal incision is left to heal without suturing. Linear salpingostomy also may be attempted if the fallopian tube is minimally ruptured and a slightly greater tubal opening is needed for removal of tubal pregnancy material.

When ectopic pregnancy results in rupture of the fallopian tube, the goal of therapeutic management is to control the bleeding and prevent hypovolemic shock. When the woman’s cardiovascular status is stable, a salpingectomy is performed to remove the affected tube and ligate bleeding vessels. Future pregnancies can still occur when only one tube is present, although the likelihood of fertility decreases. In addition, the same conditions that caused the ectopic pregnancy in the tube that was removed may exist in the other tube.

Nursing Considerations

Nursing care focuses on preventing or identifying hypovolemic shock, controlling pain, and providing psychological support for the woman who experiences an ectopic pregnancy. If methotrexate is used, the nurse must explain temporary side effects (e.g., nausea and vomiting) and the importance of communicating to the health care team bothersome drug effects or worsening symptoms that suggest rupture (e.g., pelvic, shoulder, or neck pain; dizziness or faintness; increased vaginal bleeding). The woman must be instructed to refrain from drinking alcohol or ingesting vitamins that contain folic acid, which would reduce the drug’s effectiveness. She should not have sexual intercourse until beta-hCG levels are undetectable (Cunningham et al., 2010). The importance of keeping follow-up appointments should be emphasized because medical treatment is not always successful, and surgical intervention may be needed.

The woman and her family often need emotional support to resolve emotions, which may include anger, grief, guilt, and self-blame. The woman may also be anxious about her ability to become pregnant in the future. Although the pregnancy is unsuccessful very early, the nurse should be aware that these women may feel an acute sense of loss similar to that of women suffering miscarriage. Nurses may need to clarify the physician’s explanation and to use therapeutic communication techniques that assist the woman to deal with her anxiety and grief.

Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (Hydatidiform Mole)

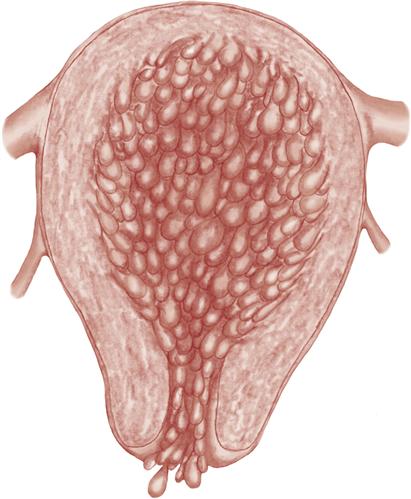

Hydatidiform mole is a form of gestational trophoblastic disease that occurs when the trophoblasts (peripheral cells that attach the fertilized ovum to the uterine wall) develop abnormally. As a result of the abnormal growth, the placenta, but not the fetus, develops. Gestational trophoblastic diseases are a spectrum of diseases that include benign hydatidiform mole and gestational trophoblastic tumors, such as invasive moles and choriocarcinoma.

Molar pregnancy is characterized by proliferation and edema of the chorionic villi. The fluid-filled villi form grapelike vesicles that may grow large enough to fill the uterus to the size of an advanced pregnancy if not diagnosed and treated (Figure 25-3). The mole may be complete, with no fetus present, or partial, in which fetal tissue or membranes are present. Malignant change and proliferation of residual trophoblastic tissue (gestational trophoblastic neoplasm, or choriocarcinoma) is a life-threatening complication. Acute respiratory distress may occur if vesicles of the hydatidiform mole enter the woman’s circulation and embolize to her lungs.

Incidence and Etiology

In the United States and Europe, the incidence of gestational trophoblastic disease is 1 in every 1000 to 1500 pregnancies. Age is a factor, with the frequency of molar pregnancies highest at both ends of reproductive life. Women who have had one molar pregnancy are at greater risk for another (Cohn, Ramaswamy, & Blum, 2009; Cunningham et al., 2010; Li, 2008).

A complete mole is believed to occur when the ovum is fertilized by a sperm that duplicates its own chromosomes while the chromosomes of the ovum are inactivated. In a partial mole, the maternal contribution is usually present, but the paternal contribution is double, and thus the karyotype is triploid (69,XXY or 69,XYY). Anomalies are present if a fetus is present.

Persistent gestational trophoblastic disease may undergo malignant change (choriocarcinoma), with possible rapid spread to distant sites such as the vagina, lung, liver, kidney, and brain.

Manifestations

Most molar pregnancies are diagnosed early by ultrasound that reveals the vesicles and no fetal gestational sac or cardiac action. Levels of beta-hCG are high because of the rapidly proliferating abnormal villi. Other signs and symptoms of a complete molar pregnancy vary with gestation, but may include:

Diagnostic Evaluation

Ultrasound examination allows a differential diagnosis to be made between two types of molar pregnancies. A complete mole shows multiple small cystic structures but no fetus. Current diagnostic techniques allow early identification and treatment of a molar pregnancy rather than later, when it ends spontaneously and is more likely to be accompanied by hemorrhage.

Therapeutic Management

Management includes (1) evacuation of the mole and (2) follow-up to detect any malignant changes in any remaining trophoblastic tissue. Before evacuation, chest imaging studies, metabolic and blood chemistry tests, and a baseline serum beta-hCG level are done. A complete blood count, laboratory assessment of clotting factors, and blood typing and crossmatching are performed in case a transfusion is needed. Treatment for hypertension or hyperemesis may be needed if these added complications have occurred (Cunningham et al., 2010; Li, 2008).

Vacuum aspiration is usually used to extract the mole. After tissue has been removed, IV oxytocin is used to contract the uterus. It is important to avoid uterine stimulation with oxytocin before evacuation. Uterine contractions can cause trophoblastic tissue to be drawn into the venous circulation, resulting in embolization of the vesicles. Curettage with a sharp curette follows the evacuation to remove all remaining molar tissue, and the tissue obtained is sent for laboratory evaluation to identify malignant changes.

Follow-up is critical to detect choriocarcinoma. The follow-up protocol involves evaluation of serum beta-hCG levels every 1 to 2 weeks until three normal prepregnancy levels are attained. The test is repeated every 1 to 2 months for up to a year and following any subsequent pregnancies (Cunningham et al., 2010; Li, 2008). Pregnancy, which normally raises beta-hCG levels, must be avoided during follow-up because it would obscure the evidence of choriocarcinoma. Oral contraceptives are the usual method.

Malignant transformation of any remaining tissue is suspected if the beta-hCG levels do not fall or if they rise after an initial fall. Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for gestational trophoblastic neoplasm (choriocarcinoma) and has a high cure rate.

Nursing Considerations

Women who have had a hydatidiform mole experience many of the same emotions as those who have had any other type of pregnancy loss. In addition, they may be anxious about the possibility of malignancy and the need to delay pregnancy (Bess & Wood, 2006).

Nursing Care

The Woman with a Hemorrhagic Condition of Early Pregnancy

Nurses play a vital role in the management of early pregnancy bleeding, regardless of its cause. Nurses monitor the condition of the pregnant woman and collaborate with the physician to provide treatment.

Assessment

Confirmation of pregnancy and length of gestation is an important initial step. Physical assessment priorities are to determine the amount and character of bleeding and the description, location, and severity of pain. Estimate the amount of vaginal bleeding by examining linen and peripads. If necessary, make a more accurate estimation by weighing the linen and peripads (1 g weight equals 1 mL volume).

Bleeding may be accompanied by pain. Uterine cramping usually accompanies spontaneous abortion; deep, severe pelvic pain is associated with ectopic pregnancy. Remember that in ruptured ectopic pregnancy, bleeding may be concealed within the abdomen and pain is the only symptom.

Assess the woman’s vital signs and urine output to evaluate her cardiovascular status. Check laboratory values for hemoglobin and hematocrit, and report abnormal values to the physician. Determine the Rh factor so that all women who are Rh-negative can receive Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) (see p. 601).

Because any spontaneous abortion may be associated with infection, assess the woman for fever, malaise, and prolonged or malodorous vaginal discharge. Teach her to continue these observations at discharge.

Determine the family’s knowledge of needed follow-up care and how to prevent complications such as infection.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The potential complications prenatal bleeding and infection are collaborative problems that should be considered in the woman with a bleeding complication in early pregnancy. Because current diagnostic techniques allow early diagnosis before hemorrhage, a nursing diagnosis that is more often encountered that would apply to early bleeding disorders is:

Expected Outcomes

The woman will verbalize understanding of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, signs and symptoms of additional complications, and measures to reduce the risk for infection. The woman will develop a plan for obtaining follow-up care, including signs or symptoms that should be reported.

Interventions

Providing Information about Tests and Procedures

Women and their families experience less anxiety if they understand what is happening. Explain necessary diagnostic procedures, such as transvaginal or abdominal ultrasound. Include the purpose of the tests, their duration, and whether the procedures cause discomfort. If surgical intervention is necessary, reinforce the explanations of the physicians who will perform the surgery and administer anesthetic. Briefly describe the reasons for blood tests, such as those for determining beta-hCG, hemoglobin or hematocrit values, coagulation factors, and blood type and screen. Explain that diagnostic and therapeutic measures are performed quickly at times to reduce blood loss.

Teaching Measures to Prevent Infection

The risk for infection is greatest during the first 72 hours after spontaneous abortion or operative procedures, but most women are discharged within a few hours of uterine evacuation. To prevent infection, peripads should be used instead of tampons until bleeding has stopped. Teach the woman to wash her hands before and after changing peripads. She should consult with the health care provider before resuming sexual intercourse.

Providing Dietary Information

Nutrition and adequate fluid intake help maintain the body’s defense against infection and help correct anemia. The woman needs foods high in iron to increase hemoglobin and hematocrit values. These foods include liver, red meat, spinach, egg yolks, carrots, and raisins. In addition, she needs foods high in vitamin C, which may increase the utilization of iron (Erick, 2012), such as citrus fruits, broccoli, strawberries, cantaloupe, cabbage, and green peppers.

Iron supplementation is often prescribed, and the woman may require information about how to reduce the gastrointestinal upset that is often experienced with oral iron. Less gastric upset is experienced when iron is taken with meals. Iron supplements with a slow release may also be better tolerated. A diet high in fiber and fluid helps prevent the commonly associated constipation.

Teaching Signs of Infection to Report

Teach the woman where she can buy a thermometer if she does not have one, and instruct her to take her temperature every 8 hours for the first 3 days at home. Tell her to seek medical help if her temperature goes above 37.8° C (100° F) or as instructed by her physician. She should also report to the physician additional signs of infection, such as vaginal discharge with foul odor, pelvic tenderness, or general malaise.

Emphasizing the Importance of Follow-up Care

A variety of follow-up procedures such as repeat ultrasound examinations or repeated determinations of serum beta-hCG levels may be necessary, depending on the pregnancy disorder. The couple who experiences recurrent abortions may become involved in complex investigations of immunologic or genetic abnormalities. Teaching about contraceptive use may be needed before discharge.

The nurse should acknowledge the couple’s grief, which often manifests as anger. Many women have guilt feelings that must be recognized. They often need repeated reassurance that the loss was not caused by anything they did or by anything they neglected. Older mothers are often more concerned about pregnancy loss or the need to delay pregnancy after gestational trophoblastic disease because their age imposes limits for successful subsequent pregnancy. A woman may be anxious about the possible development of choriocarcinoma as well.

Evaluation

Hemorrhagic Conditions of Late Pregnancy

After 20 weeks of pregnancy, the two major causes of hemorrhage are disorders of the placenta called placenta previa and abruptio placentae. Abruptio placentae may be further complicated by DIC.

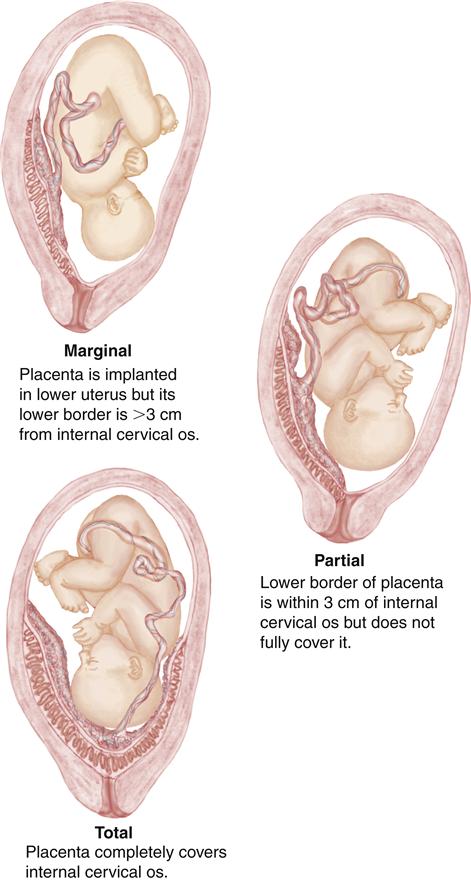

Placenta Previa

Placenta previa is an implantation of the placenta in the lower uterus, near the fetal presenting part. Use of both abdominal and transvaginal ultrasound allows measurement of the distance between the internal cervical os and the lower border of the placenta to classify placenta previa (Figure 25-4):

Marginal placenta previa is common in early ultrasound examinations and often appears to “move” upward and away from the internal cervical os. The growing placenta does not move, however, but is drawn upward as the myometrium beneath it develops with pregnancy progression.

Incidence and Etiology

Placenta previa occurs in about 1 in 200 to 300 pregnancies in the United States. It is more common in older women, multiparas, women who have had cesarean births, and women who have had suction curettage for induced or spontaneous abortion. It is also more likely to recur in a future pregnancy. Women of Asian or African ethnicity have an increased risk. Smoking and cocaine use are also associated with placenta previa. Placenta previa is also more likely to occur if the fetus is male (Cunningham et al., 2010; Hull & Resnik, 2009; Kay, 2008).

Manifestations

The classic sign of placenta previa is the sudden onset of painless uterine bleeding in the latter half of pregnancy. Many cases of placenta previa, however, are diagnosed by ultrasound examination before the onset of bleeding. Bleeding occurs when the placental villi are torn from the uterine wall, resulting in hemorrhage from the uterine vessels. Bleeding is typically painless because it does not occur in a closed cavity and therefore does not cause pressure on adjacent tissue. Bleeding may be scanty or profuse, and it may cease spontaneously, only to recur later.

Bleeding may not occur until labor starts, when cervical changes disrupt placental attachment. The admitting nurse may be unsure whether the bleeding represents heavy “bloody show” or is a sign of a placenta previa. Also the woman may have pain associated with the bleeding because of active labor contractions.

Digital examination of the cervical os when placenta previa is present can cause additional placental separation or can tear the placenta itself, causing severe maternal and fetal bleeding. Until the location and position of the placenta are verified by ultrasound to determine the cause of excessive vaginal bleeding, manual examinations and administration of oxytocin to stimulate labor should be avoided. Manual vaginal examination or contraction stimulation can interrupt connections between maternal and placental vessels if the placenta is attached low in the uterus.

Therapeutic Management

When the diagnosis of placenta previa is confirmed, medical interventions are based on the condition of the mother and fetus. The woman is evaluated carefully to determine the amount of hemorrhage, and external electronic fetal monitoring is initiated to determine if the patterns are reassuring (see Chapter 17). A third consideration is the fetal gestational age.

Options for management include conservative management if the mother’s cardiovascular status is stable and the fetus is immature and has a reassuring status by monitoring and ultrasound examination. Delaying birth may increase birth weight and maturity and allow administration of corticosteroids to the mother to speed maturation of the fetal lungs. Conservative management may take place in the home or hospital.

Nursing Considerations

Nursing care may be provided in the home or the hospital if conservative management is chosen by the caregivers.

Home Care

Criteria for outpatient management include (Hull & Resnik, 2009; Kay, 2008):

• The woman is clinically stable, with no evidence of active bleeding.

• The woman can maintain bed rest at home.

• Home is within a reasonable distance from the hospital.

• Emergency transportation is available 24 hours a day.

Nurses help the family develop a plan of care that includes bed rest as ordered, the presence of a responsible adult at all times, and ready transportation to the hospital. Nurses must teach the mother and the family what to monitor and emphasize the importance of (1) assessing vaginal discharge or bleeding after each urination or bowel movement, or more often as needed; (2) counting fetal movements daily (see Chapter 15); (3) assessing uterine activity daily; and (4) omitting sexual intercourse to prevent disruption of the placenta. Spontaneous membrane rupture can occur at any time and with varying amounts of fluid loss, so the woman and her family should be taught to return to the hospital for evaluation. Home care nurses may provide assessments of uterine activity (cramping, regular or sporadic contractions), bleeding, fetal activity, and adherence to the prescribed treatment plan with regular phone contact. In addition, nurses can make regular home visits for maternal-fetal assessments such as nonstress tests with portable equipment. The family is instructed to report decreased fetal movements, uterine contractions, or increased vaginal bleeding at once.

Nurses should also provide specific, accurate information about the condition of the fetus. For example, parents are reassured when they hear that the fetal heart rate is within the expected range and daily “kick counts” are reassuring of fetal well-being. Moreover, it may be necessary for nurses to help the family understand the physician’s plan of care, such as a cesarean delivery with possible blood transfusion.

Inpatient Care

Hospitalization is needed if the woman does not meet the criteria for home care. Nursing assessments in the hospital are similar to those done at home and are focused on observing the presence and character of bleeding and looking for signs of preterm labor. Periodic nonstress tests and biophysical profiles provide added information about the fetal condition. A significant change in fetal heart activity, an episode of increased vaginal bleeding, or signs of preterm labor should be reported immediately to the physician. Rupture of membranes should be reported, whether when on home care or in the hospital.

At times, conservative management is not an option. For example, delivery by cesarean birth is often scheduled if the fetus is greater than 36 weeks of gestation and the lungs are mature. Immediate delivery of an immature fetus may be necessary if bleeding is excessive and does not stop, the woman’s cardiovascular status is unstable, or there are signs of fetal compromise.

Nurses prepare the woman for surgery whenever cesarean birth becomes necessary (see Chapter 19). Signed consents for cesarean birth, blood transfusion, and anesthesia should be kept current for women with late pregnancy bleeding, because surgery may be required suddenly. IV access may be maintained with a saline lock if a woman has late pregnancy bleeding, but immediate delivery is not necessary. Crossmatched blood may be kept on hold. When many emergency preparations occur at once, the nurse should constantly provide appropriate reassurance to reduce the woman’s anxiety and that of her family.

Abruptio Placentae

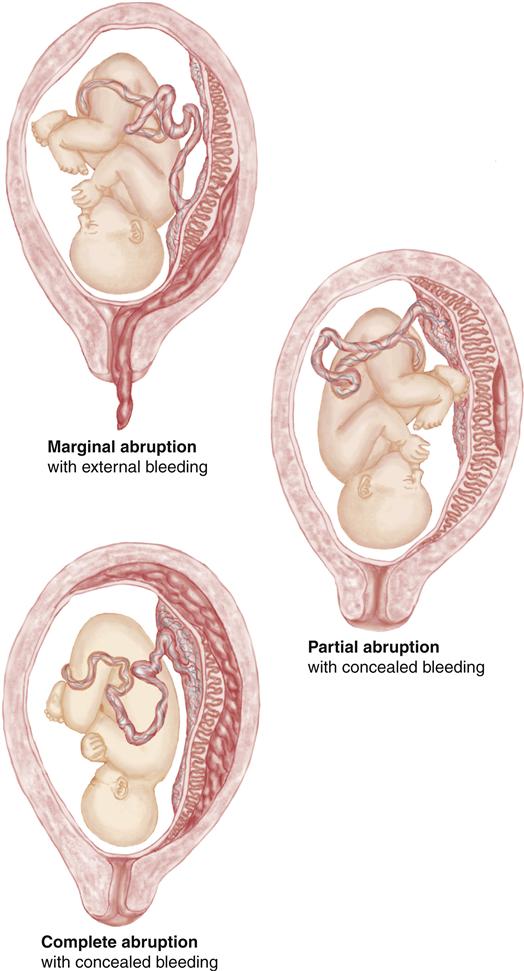

Separation of a normally implanted placenta before the fetus is born (called abruptio placentae, placental abruption; or premature separation of the placenta) occurs when there is bleeding and formation of a hematoma on the maternal side of the placenta. As the clot expands, further separation occurs. The severity of the complication depends on the amount of bleeding and the size of the hematoma. The hematoma can expand and thus obliterate intervillous spaces where fetal gas and nutrient exchange occurs. Moreover, fetal vessels will be disrupted as placental separation occurs, resulting in fetal as well as maternal bleeding. Small abruptions may, however, be self-limiting (Cunningham et al., 2010; Hull & Resnik, 2009; Kay, 2008).

The major danger for the woman is hemorrhage and consequent hypovolemic shock and clotting abnormalities such as DIC (see p. 578). The major dangers for the fetus are related to anoxia, blood loss, and preterm birth.

Incidence and Etiology

The incidence of abruptio placentae varies but occurs in about 0.5% to 1% of pregnancies. However, abruptio placentae accounts for 10% to 15% of perinatal deaths. The cause of abruptio placentae is unknown, but risk factors include hypertension, smoking, multigravida status, abdominal trauma from a motor vehicle accident or domestic violence, and a history of a previous premature separation of the placenta. Maternal use of cocaine, which causes vasoconstriction, or narrowing of the vessel lumen, in the endometrial arteries, is a leading cause of abruptio placentae (Cunningham et al., 2010; Hull & Resnik, 2009; Kay, 2008).

Recently identified factors that are associated with abruptio placentae can be grouped under the classification of autoimmune antibodies that result in various coagulopathies. This group includes anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant. Other coagulopathies may be caused by genetic factors, such as a factor V Leiden mutation. Women who have these coagulopathies have a tendency to form clots in the placenta. Hypertension, a frequent companion of abruptio placentae, occurs more frequently in women with some autoimmune disorders as well.

Manifestations

Five classic signs and symptoms of abruptio placentae are:

• Vaginal bleeding, which may not reflect the true amount of blood loss

• Abdominal and low back pain that may be described as aching or dull

• Uterine irritability with frequent low-intensity contractions

• High uterine resting tone identified by use of an intrauterine pressure catheter

• Uterine tenderness that may be localized to the site of the abruption

Additional signs include back pain, nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns, signs of hypovolemic shock, and fetal death.

Hemorrhage from abruptio placentae may be concealed or apparent. In either type, the placental abruption may be complete or partial. Concealed hemorrhage is bleeding that occurs behind the placenta while the margins remain intact. The hemorrhage is apparent when bleeding separates or dissects the membranes from the endometrium and blood flows out through the vagina. The amniotic fluid often has a classic “port-wine” color. Figure 25-5 illustrates variations of abruptio placentae with external and concealed bleeding. The actual amount of blood lost may be greater than the visible bleeding. Signs of maternal hypovolemia may be present when there is little or no external bleeding.

Abdominal pain is also related to the type of separation. It may be sudden and severe when there is bleeding into the myometrium (uterine muscle) or intermittent and difficult to distinguish from labor contractions. The abdomen may become exceedingly firm (boardlike) and tender, making palpation of the fetus difficult. Ultrasound examination is helpful to rule out placenta previa as the cause of bleeding, but it cannot be used to diagnose abruptio placentae because the placental separation and bleeding look similar on ultrasound images.

Therapeutic Management

A woman who exhibits signs of abruptio placentae should be hospitalized and evaluated at once. Evaluation focuses on the condition of the fetus and the cardiovascular status of the mother.

Although rare, conservative management may be initiated if the abruption is mild and the fetus is less than 34 weeks of gestation, shows no signs of distress, and if bleeding is minimal. Measures include bed rest and may include administration of tocolytic medications to decrease uterine activity. Serial Kleihauer-Betke (K-B) tests determine if fetal bleeding is worsening. For the Rh-negative woman, RhoGAM is ordered to prevent maternal Rh sensitization.

Women may be observed for 24 hours after significant abdominal trauma such as a motor vehicle collision or domestic violence, because it may take this long for an abruptio placentae to become evident. If they are not having contractions after the trauma, and the fetal heart rate pattern and laboratory studies are reassuring, monitoring for 4 to 6 hours may be sufficient (Bobrowski, 2011).

If signs of fetal compromise are present or if the woman or her fetus exhibit signs of excessive bleeding, either obvious or concealed, prompt delivery of the fetus is necessary. Intensive monitoring of both the woman and the fetus is essential because rapid deterioration of either can occur. One or more large-gauge IV lines should be placed for replacement of fluid and blood.

Nursing Considerations

If immediate cesarean delivery is necessary, the woman may feel frightened and powerless as the health care team hurriedly prepares her for surgery. She may be experiencing severe pain and be aware of the risks to her baby and herself. If at all possible, nurses should explain anticipated procedures to the woman and her family to reduce their feelings of fear and anxiety.

Excessive bleeding and fetal hypoxia are always major concerns with abruptio placentae, and nurses are responsible for continuous monitoring of both the expectant mother and the fetus so that problems can be detected early, before the condition of the woman or the fetus deteriorates.

Nursing Care

The Woman with a Hemorrhagic Condition of Late Pregnancy

Assessment

For hemorrhagic conditions of late pregnancy, medical and nursing assessments are concurrent. Some assessments are delayed or not done if the maternal or fetal condition is not reassuring. The priority assessments are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree