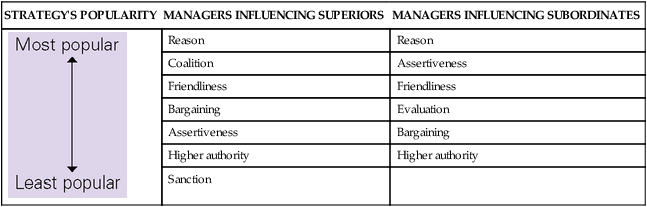

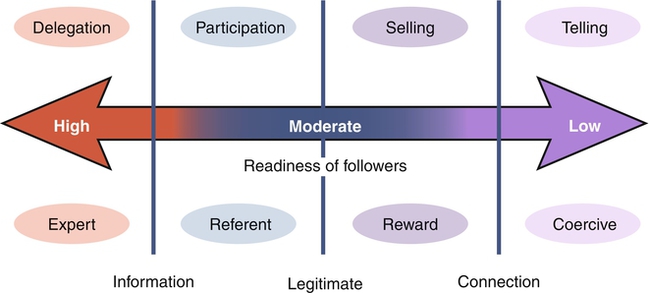

In 2009, national health expenditures grew 4.0% to $2.5 trillion, or $8086 per person, and accounted for 17.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011). Further, the number of Americans without health insurance coverage rose to 49.9 million in 2010 from 49 million in 2009 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2011. Despite the abundance of government and private sector safety initiatives, health care errors persist at alarming rates. Adverse events occurred in approximately 33% of hospital admissions (Classen et al., 2011). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report (CHDIR, 2011), health care quality and access are suboptimal, especially for minority and low-income groups; and although quality is improving, access and disparities are not improving. • Nurses should practice to the full extent of their education and training. • Nurses should achieve higher levels of education and training through an improved education system that promotes seamless academic progression. • Nurses should be full partners, with physicians and other health care professionals, in redesigning health care in the United States. • Effective workforce planning and policy making require better data collection and information infrastructure (IOM, 2010). The enactment of the health care reform law and issuance of the IOM report on the future of nursing provide unlimited opportunities for the profession to establish a power base and become a force in the U.S. health care system. Manojlovich (2007) noted that power is necessary to influence patients, physicians, and other health care professionals, as well as each other. Increasingly, nurse leaders recognize that understanding and acknowledging power and learning to seek and wield it appropriately are critical if nurses’ efforts to shape their own practice and the broader health care environment are to be successful (Schira, 2004). Powerless nurses are ineffective nurses, and the consequences of nurses’ lack of power have recently come to light (Manojlovich, 2007). Powerless nurses are less satisfied with their jobs and more susceptible to burnout and depersonalization. Lack of nursing power may also contribute to poorer patient outcomes (Manojlovich, 2007). As the largest health care profession, nursing must use power and influence as a legitimate tool to facilitate change in health care organizations and the health care system. The following are the three formal dimensions of power (Bacharach & Lawler, 1980): The relational aspect of power suggests that power is a property of a social relationship. Many classic definitions (Blau, 1964; Kaplan, 1964) indicate that power has to do with relationships between two or more actors in which the behavior of one is affected by the other. Weber (1947) defined power as “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will, despite resistance, and regardless of the basis on which this probability rests” (p. 52). Dahl (1957) also defined power as an interactive process and stated that “A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something B would not otherwise do” (pp. 202-203). The second formal aspect, the dependency aspect of power, was addressed by Emerson (1957), who suggested that power resides implicitly in the other’s dependency. Dependency is particularly evident in organizations that require interdependence of personnel and subunits. Daft (2013) defined interdependence as the extent to which departments depend on each other for resources or materials to accomplish their task. The highest level of interdependence is reciprocal interdependence. Reciprocal interdependence exists when the output of operation A is the input to operation B, and the output of operation B is the input back again to operation A. Daft noted that hospitals are excellent examples of reciprocal interdependence because they provide coordinated services to patients. Empowerment is a corollary concept to power in groups and organizations. Empowerment is defined as giving individuals the authority, responsibility, and freedom to act on what they know and instilling in them belief and confidence in their own ability to achieve and succeed (Kramer & Schmalenberg, 1990). Thus empowerment has two meanings: the transfer of actual power and the inspiring of self-confidence. Both aspects enable others to act. Empowerment is a key leadership component. Empowerment for nurses may consist of three components: a workplace that has the requisite structures to promote empowerment, a psychological belief in one’s ability to be empowered, and acknowledgment that there is power in the relationships and caring that nurses provide. A more thorough understanding of these three components may help nurses become empowered and use their power for better patient care (Manojlovich, 2007). Psychological empowerment is a psychological response to empowered work environments and consists of four components: meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact (Spreitzer, 1995). Psychologically empowered employees feel that the requirements of the job are congruent with their own beliefs and values, which gives the job greater meaning. They are confident in their ability to perform the job, have control over their work, and have an impact on important organizational outcomes. Employees with low levels of psychological empowerment have less capacity to cope with organizational stressors and are more likely to respond passively. Laschinger and colleagues (2007) found that higher levels of structural empowerment were predictive of greater psychological empowerment, which in turn resulted in lower levels of emotional exhaustion and higher job satisfaction. Creating conditions that foster a sense of empowerment in managers is thus important to their well-being and retention. Employee empowerment became a popular topic in the 1990s, especially in the business literature. With an emphasis on customer service and improving the bottom line through capitalizing on the creative and innovative energy of employees, businesses sought a strategic advantage. Empowerment programs were developed to improve productivity, lower costs, or raise customer satisfaction. However, growing evidence suggests that these empowerment programs fail to meet either managers’ or employees’ expectations, possibly because although empowerment programs promise employees power, they may not deliver on the promise (Hardy & Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1998). Empowerment initiatives take two forms. First is the relational approach. The aim here is to improve performance by decentralizing power by delegating power, authority, and decision making. In theory, this reduces organizational barriers to getting the job done. Self-managing teams are one example (Hardy & Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1998). Authority and influence are two major content dimensions of power (Bacharach & Lawler, 1980). There have been three conceptualizations of authority and influence: (1) some authors equate these terms; (2) others tend to equate power with influence and assert that authority is a special case of power; (3) still others view authority and influence as distinctly different dimensions of power. Several points of contrast are summarized in Table 10-1. TABLE 10-1 Authority and Influence Contrasted 1. Assertiveness means expressing one’s own position to another without inhibiting the rights of others. 2. Ingratiation means trying to make the other person feel important—giving praise or sympathizing. Ingratiation is attempting to advance oneself by trying to make another person feel important. 3. Rationality means using logical and rational arguments, providing pertinent information, presenting reasons, and laying out an idea in a logical, structured way. 4. Sanctions are threats. Positive sanctions, or rewards, are addressed within motivation mechanisms. 5. Exchange means that to persuade, an exchange is offered; this is sometimes called “scratching each other’s back.” 6. Upward appeal means going to a higher authority—the childhood threat of “if you don’t play by my rules, I am going to go tell Mom.” Upward appeal simply means taking the appeal to a higher authority to arbitrate. 7. Blocking means deliberately keeping others from getting their way, threatening to stop working with them, ignoring them, not being friendly, or simply attempting to make sure others cannot accomplish their aims. 8. Coalitions are the result of a group of people getting together to speak or negotiate as one voice. In their three-nation study of managerial influence styles, Kipnis and colleagues (1984) identified the most to least popular strategies (Table 10-2). TABLE 10-2 Most to Least Managerial Influence Strategies Used in all Countries Modified from Kipnis, D., Schmidt, S.M., Swaffin-Smith, C., & Wilkinson, I. (1984). Patterns of managerial influence: Shotgun managers, tacticians, and bystanders. Organizational Dynamics, 12(3), 58-67. Yukl and Falbe (1991) continued the work of Kipnis and colleagues (1980). They developed an instrument, the Influence Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ), to measure the influence behavior of managers. In later studies, the IBQ was developed further, and psychometric tests were performed (Yukl et al., 1992, 1993). The nine tactics cover a wide range of influence behavior relevant for managerial effectiveness or, in a broader sense, for getting things done in an organization. Influence tactics are identified in Table 10-3. TABLE 10-3 Definitions of Influence Tactics From Yukl, G., Falbe, C., & Joo, Y.Y. (1993). Patterns of influence behavior for managers. Group and Organization Management, 18(1), 5-28. Although multiple mechanisms of power have been identified, the most widely accepted power base classification is French and Raven’s (1959) five sources of power. Their original conceptualization identified the following five power sources (Box 10-1): (1) reward, (2) coercive, (3) expert, (4) referent, and (5) legitimate. Raven and Kruglanski (1975) and Hersey and colleagues (1979) identified two additional sources of power: (1) connection power, and (2) information power. A third type of power also has been identified: (3) group decision-making power (Liberatore et al., 1989). These three other sources of power are related to groups and organizations specifically, as opposed to French and Raven’s (1959) original five sources of power, which relate more to an individual. Another source of power is derived from group decision making. This means that a creative synergy and force is created when a group comes together, makes decisions, and acts as a united front. For example, some professional groups have formed strong lobbies to influence state and national legislation. With more than 3.1 million licensed registered nurses in the United States (American Nurses Association, 2011), group decision making with resultant unity of action could be a powerful strategy for nurses to use to advance nursing’s goals or policy agenda. Persuasive power is an additional source of power identified by later researchers investigating French and Ravens’ (1959) taxonomy. Persuasive power refers to skill in making rational appeals (Yukl & Falbe, 1991). Yukl and Falbe (1991) differentiated between position power and personal power. According to these authors, position power consists of legitimate, reward, coercive, and information power. Personal power consists of expert, referent, persuasive power. Kanter’s theory has been tested extensively in nursing populations. These populations have been found to be only moderately empowered, with varying levels of access to information, support, opportunity, and resources (Laschinger & Havens, 1997; Laschinger et al., 2001b). Higher levels of structural empowerment have been associated with higher levels of organizational commitment (Laschinger et al., 2000), greater participation in organizational decision making (Laschinger et al., 1997), higher levels of job autonomy (Sabiston & Laschinger 1995), higher levels of job satisfaction (Laschinger & Havens 1997; Laschinger et al., 2001a), greater organizational trust (Laschinger et al., 2000), and a greater likelihood of feeling respected in the workplace (Faulkner & Laschinger, 2008). All these findings lend support to Kanter’s theory. Kotter (1979) maintained that the basic methods for acquiring and maintaining power are gaining control over tangible resources, obtaining information and control of information channels, and establishing favorable relationships. Basically, acquiring and maintaining power is an exercise in developing credibility by getting people to feel obligated in some way, building a good professional reputation through visible achievement, encouraging identification by trying to look and behave in ways that others respect, and finally, creating perceived dependence either for help or security. Control of information and resources and development of support systems are common elements in both Kanter’s and Kotter’s theories. Subunit or horizontal power pertains to relationships across departments. Daft (2013) noted that although each department makes a unique contribution to organizational success, some contributions are greater than others. Pfeffer (1981) identified the following structural determinants of power within organizations: • Power is derived from dependence. Simply stated, power comes from having something that someone else wants or needs and being in control of the performance or resource so that there are few, if any, alternative sources for obtaining what is desired. • Power is derived from providing resources. Organizations require a continuing provision of resources such as personnel, money, customers, and technology in order to continue to function. Those subunits or individuals within the organization that can provide the most critical and difficult to obtain resources come to have power in organizations. Their power is derived from their ability to furnish those resources upon which the organization most depends. • Power is derived from coping with uncertainty. Coping with uncertainty is a critical resource in the organization since it ensures organizational survival and adaptation to external constraints. • Power is derived from being irreplaceable. Members must not only provide a critical resource for the organization but also prevent themselves from being readily replaced in that function. The degree of substitutability is not a fixed thing, however, so it might be expected that various strategies will be employed by individuals and subunits who are interested in enhancing their power within the organization. Some of these might involve the availability of documentation, use of specialized language, centralization of knowledge, and maintenance of externally based sources of expertise. • Power is derived from the ability to affect the decision process. Because decisions are made in a sequential process, it is possible for an individual to acquire power because of his or her ability to affect the premises of basic values or objectives used in making any decision. A person can gain power by influencing the information about the alternatives being considered in the decision process. • Power is derived if there is a shared consensus within the organizational subunit. If individuals within a subunit share a common perspective, set of values, or definition of the situation, they are likely to act and speak in a consistent manner and present to the larger organization an easily articulated and understood position and perspective. Such a consensus can serve to enhance the power of the subunit among other organizational members. The Theory of Group Power within organizations was developed from a synthesis and reformulation of King’s (1981) interacting systems framework and the Strategic Contingencies Theory of power (Hickson et al., 1971). Variables within the Strategic Contingencies Theory of power and their relationships were reformulated within King’s framework. These variables relate to controlling the effects of environmental forces, position, resources, and role. Sieloff (2003) noted that although nursing groups are proposed to have a power capacity resulting from controlling the effects of environment forces, position, resources, and role, not all nursing groups have acted powerfully. Therefore four additional concepts were added to the theory as variables that intervened between a nursing group’s power capacity and its ability to actualize that power capacity. These concepts are communication competency, goal/outcome competency, nurse leader’s power competency, and power perspective. Every nursing group has a power capacity. The group has the potential to achieve its goals and become a more visible contributor to the progress of the organization. The value of the theory is that it provides nurse leaders at all levels with strategies that could be implemented to improve a nursing group’s actualized power (Sieloff, 2003). According to Robbins and Judge (2011), leadership and power are two different concepts and need to be defined separately. Leadership is focusing on goal achievement in conjunction with followers. Power is used as a way to accomplish the goal, and often followers contribute to accomplishing the goal. Leaders focus on using their leadership downward to influence others to help them achieve their tasks. On the other hand, power is deployed to influence and to gain something upward or laterally. to assess and predict style choice and power source use based on the situation and readiness of followers. Readiness is the ability and willingness of individuals or groups to take responsibility for directing their own behavior in a situation. There appears to be a direct relationship between the level of readiness in individuals and groups and the power base type that has a high probability of effectiveness (Figure 10-1). Readiness is a task-specific concept. At the lowest level of readiness, coercive power is most appropriate. As people move to higher readiness levels, connection power, then reward, then legitimate, then referent, then information, and finally, expert power impact the behavior of people. At the highest level, the followers have competence and confidence, and they are most responsive to expert power (Hersey et al., 2008). If power is the basic energy needed to initiate and sustain action, then power is a quality without which a leader cannot lead. Power is fundamental to leadership, in that leadership may be the wise use of power. This is especially true for transformative leadership (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). Power need is highly desirable in leaders and managers because power is necessary in influencing others. Assertiveness and self-confidence are associated with power and leadership. Leadership may be characterized as power in the service of others (Kouzes & Posner, 1987). For nurses, this may mean that they need to view power as an integral part of their professional roles in care management and client advocacy. Nursing leadership requires a willingness and ability to take on a power role and to expand the use of power bases. The same turbulent health care environment that demands the use of power also creates the conditions that breed conflict. Health care in the United States has gone through dramatic changes in recent decades. Change increases conflict in organizations. Gerardi (2004) summarized the direct and indirect consequences of conflict in terms of costs, including direct costs such as the following: • Litigation costs that include attorneys’ fees, expert testimony, deposition, lost work time, and document production • Decreased managerial productivity as a result of time spent on resolving conflict • Regulatory fines for noncompliance or loss of contracts or provider status with insurers and Medicare/Medicaid • Costs associated with increased expenditures for patients with preventable, poor or adverse outcomes Indirect costs include the following: • Loss of team morale, loss of motivation for organizational change, damaged workplace relationships, and unresolved tensions that lead to future conflicts • Lost opportunities for pursuing capital purchases, expanding services, enhancing customer satisfaction programs, and developing staff and leaders • Cost to reputation of an organization and of care professionals; negative publicity/media coverage • Loss of strategic market positioning because of public disclosure of information regarding the dispute/bad public relations • Increased incidence of disruptive behavior by staff and medical professionals • Emotional costs including the turmoil for those involved in conflict. There is evidence in the literature that conflict leads to bullying. Leymann (1996) and Einarsen and colleagues (1994) claimed that a bullying case typically is triggered by a work-related conflict. Matthiesen and colleagues (2003) noted that bullying can be described as certain subsets of conflict. When behavior similar to bullying occurs among health care providers from different disciplines, the term disruptive behavior is often used to name the behavior (Dumont et al., 2012). Conflict, as included in definitions of disruptive behaviors, is defined as “any inappropriate behavior, confrontation, or conflict, ranging from verbal abuse to physical and sexual harassment” (Rosenstein, 2002, p. 27). The Joint Commission (2011) acknowledged that unresolved conflict and disruptive behavior can adversely affect safety and quality of care, and they issued leadership standards calling for a stop to disruptive and inappropriate behaviors and a process to manage them. The Joint Commission requires that accredited institutions have a code of conduct that defines acceptable, disruptive, and inappropriate behaviors and that leaders have a process for managing them. In 2011, the elements of performance standards language were changed from “disruptive behavior” to “behavior or behaviors that undermine the culture of safety” (The Joint Commission Online, 2011). Health care organizations must find ways of managing conflict and developing effective working relationships to create healthy work environments and cultures of safety. The effects of unresolved conflict on clinical outcomes, staff retention, and the financial health of the organization lead to many unnecessary costs that divert resources from clinical care (Gerardi, 2004). In addition, unresolved conflict and behaviors that undermine a culture of safety diminish the nursing profession and limit the profession’s power to facilitate change in health care organizations and the health care system. Understanding how to maneuver around and manage conflict situations increases the ability to be more effective in both personal and professional roles. According to Kelly, a generally accepted definition of conflict does not exist (Kelly, 2006). Conflict is defined here as a clash or struggle that occurs when a real or perceived threat or difference exists in the desires, thoughts, attitudes, feelings, or behaviors of two or more parties (Deutsch, 1973). It exists as a tension or struggle arising from mutually exclusive or opposing actions, thoughts, opinions, or feelings. Conflict can be internal or external to an individual or group. It can be positive as well as negative. Organizational conflict is defined as the struggle for scarce organizational resources (Coser, 1956). Values, goals, roles, or structural elements may be the specific locus of the struggle for scarce organizational resources. For example, two parties may be in opposition because of perceived differences in goals, a struggle over scarce resources, or interference in goal attainment. This opposition prevents cooperation (Deutsch, 1973). Job conflict is defined as a perceived opposition or antagonistic process at the individual-organization interface (Gardner, 1992). Conflict levels have an effect on productivity, morale, and teamwork in organizations A review of the classic literature revealed several definitions of conflict. Social conflict is a struggle between opponents over values and claims to scarce status, power, and resources (Coser, 1956). According to Deutsch (1973), a conflict exists whenever incompatible activities occur or when one party is interfering, disrupting, obstructing, or in some other way making another party’s actions less effective. The factors underlying conflict are threefold: (1) interdependence, (2) differences in goals, and (3) differences in perceptions. Conrad (1990) indicated that conflicts are communicative interactions among people who are interdependent and who perceive that their interests are incompatible, inconsistent, or in tension. Conflict is thus the interaction of interdependent people who perceive incompatible goals and interference from each other in achieving those goals (Folger et al., 1997). Walton (1966) defined conflict as opposition processes in any of several forms (e.g., hostility, decreased communication, distrust, sabotage, verbal abuse, coercive tactics). Interpersonal conflict is a dynamic process that occurs between interdependent parties as they experience negative emotional reactions to perceived disagreements and interference with the attainment of their goals (Barki & Hartwick, 2001).

Power and Conflict

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

POWER

DEFINITIONS

Empowerment

AUTHORITY AND INFLUENCE

AUTHORITY

INFLUENCE

Authority is the static, structural aspect of power in organizations.

Influence is the dynamic, tactical element.

Authority is the formal aspect of power.

Influence is the informal aspect.

Authority refers to the formally sanctioned right to make decisions.

Influence is not sanctioned by the organization and is, therefore, not a matter of organizational rights.

Authority implies involuntary submission by subordinates.

Influence implies voluntary submission and does not necessarily entail a superior-subordinate relationship.

Authority flows downward, and it is unidirectional.

Influence is multidirectional and can flow upward, downward, or horizontally.

The source of authority is solely structural.

The source of influence may be personal characteristics, expertise, or opportunity.

Authority is circumscribed.

The domain, scope, and legitimacy of influence are typically ambiguous.

Influence Tactics

STRATEGY’S POPULARITY

MANAGERS INFLUENCING SUPERIORS

MANAGERS INFLUENCING SUBORDINATES

![]()

Reason

Reason

Coalition

Assertiveness

Friendliness

Friendliness

Bargaining

Evaluation

Assertiveness

Bargaining

Higher authority

Higher authority

Sanction

TACTIC

DEFINITION

Rational persuasion

The agent uses logical arguments and factual evidence to persuade the target that a proposal or request is viable and likely to result in the attainment of task objectives.

Inspiration appeals

The agent makes a request or proposal that arouses target enthusiasm by appealing to his or her values, ideals, and aspirations or by increasing target self-confidence.

Consultation

The agent seeks target participation in planning a strategy, activity, or change for which target support and assistance are desired, or the agent is willing to modify a proposal to deal with target concerns and suggestions.

Ingratiation

The agent uses praise, flattery, friendly behavior, or helpful behavior to get the target in a “good mood” or to think favorably of the agent before asking for something.

Personal appeals

The agent appeals to target feelings of loyalty and friendship toward him or her before asking for something.

Exchange

The agent offers an exchange of favors, indicates willingness to reciprocate at a later time, or promises a share of the benefits if the target helps to accomplish a task.

Coalition tactics

The agent seeks the aid of others to persuade the target to do something or uses the support of others as a reason for the target to agree as well.

Legitimating tactics

The agent seeks to establish the legitimacy of a request by claiming the authority or right to make it or by verifying that it is consistent with organizational policies, rules, practices, or traditions.

Pressure

The agent uses demands, threats, frequent checking, or persistent reminders to influence the target to do what the agent wants.

SOURCES OF POWER

Individual Sources of Power

Other Sources of Power

THE POWER OF THE SUBUNIT

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

POWER AND LEADERSHIP

CONFLICT

BULLYING AND DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR

DEFINITIONS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access