Postpartum Adaptations

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain the physiologic changes that occur during the postpartum period.

• Discuss the role of the nurse in health education and identify important areas of teaching.

• Compare nursing assessments and care for women who have undergone cesarean birth and vaginal birth.

• Explain the process of bonding and attachment, including maternal touch and verbal interactions.

• Identify maternal concerns and how they change over time.

• Discuss the cause, manifestations, and interventions for postpartum blues.

• Describe the processes of family adaptation to the birth of a baby.

• Explain factors that affect family adaptation.

• Discuss cultural influences on family adaptation.

• Describe assessments and interventions for postpartum psychosocial adaptations.

• Describe criteria for discharge and available health care services.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

The first 6 weeks after the birth of an infant are known as the postpartum period, or puerperium. During this time, mothers experience numerous physiologic and psychosocial changes. Many postpartum physiologic changes are retrogressive—that is, changes that occurred in body systems during pregnancy are reversed as the body returns to the nonpregnant state. Progressive changes such as the initiation of lactation also occur.

Reproductive System

Involution of the Uterus

Involution refers to the changes the reproductive organs, particularly the uterus, undergo after childbirth to return to their nonpregnant size and condition. Uterine involution entails three processes: (1) contraction of muscle fibers, (2) catabolism (the process of converting cells into simpler compounds), and (3) regeneration of uterine epithelium. Involution begins immediately after delivery of the placenta, when uterine muscle fibers contract firmly around maternal blood vessels at the area where the placenta was attached. This contraction controls bleeding from the area left denuded when the placenta separated. The uterus becomes smaller as the muscle fibers, which have been stretched for many months, contract and gradually regain their former contour and size.

The enlarged uterine muscle cells are affected by catabolic changes in protein cytoplasm that cause a reduction in individual cell size. The products of this catabolic process are absorbed by the bloodstream and excreted in the urine as nitrogenous waste.

Regeneration of the uterine epithelial lining begins soon after childbirth. The outer portion of the endometrial layer is expelled with the placenta. Within 2 to 3 days, the remaining decidua (endometrium during pregnancy) separates into two layers. The first layer is superficial and is shed in lochia. The basal layer remains to provide the source of new endometrium. Regeneration of the endometrium, except at the site of placental attachment, occurs by 16 days after birth (Blackburn, 2013).

The placental site, which is about 8 to 10 cm (3 to 4 inches) in diameter, heals by a process of exfoliation (scaling off of dead tissue) (James, 2008). New endometrium is generated from glands and tissue that remain in the lower layer of the decidua after separation of the placenta (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). This process leaves the uterine lining free of scar tissue, which would interfere with implantation of future pregnancies. Healing at the placental site takes approximately 6 weeks.

Descent of the Uterine Fundus

The location of the uterine fundus (top of the uterus above the openings of the fallopian tubes) helps determine whether involution is progressing normally. Immediately after delivery, the uterus is about the size of a large grapefruit and weighs approximately 1000 g (2.2 lb). The fundus can be palpated midway between the symphysis pubis and umbilicus and in the midline (middle) of the abdomen. Within 12 hours the fundus rises to about the level of the umbilicus (Blackburn, 2013; James, 2008).

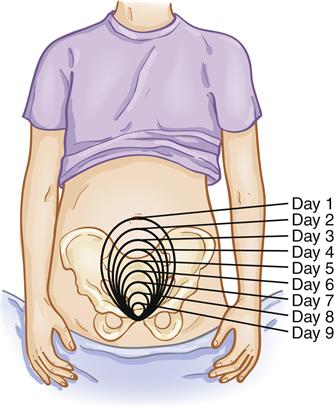

The fundus descends by approximately 1 cm, or one fingerbreadth, per day, so that by the 14th day it is in the pelvic cavity and cannot be palpated abdominally (Blackburn, 2013) (Figure 20-1). The fundus may be slightly higher in multiparas or in women who had an overdistended uterus. When the process of involution does not occur properly, subinvolution occurs. Subinvolution can cause postpartum hemorrhage (see Chapter 28).

Descent is documented in relation to the umbilicus. For example, U − 1 or ↓ 1 indicates the fundus is palpable 1 cm or fingerbreadth below the umbilicus. Within a week, the weight of the uterus decreases to about 500 g (1 lb); at 4 weeks, the uterus weighs about 100 g (3.5 oz) or less (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Afterpains

Etiology

Intermittent contractions, known as afterpains, are a source of discomfort for many women. The discomfort is more acute for multiparas because repeated stretching of muscle fibers leads to loss of muscle tone that causes alternate contraction and relaxation of the uterus. The uterus of a primipara tends to remain contracted, but she may also experience severe afterpains if her uterus has been overdistended by multifetal pregnancy, a large infant, hydramnios, or if retained blood clots are present. Oxytocin released from the posterior pituitary during breastfeeding may cause strong contractions of the uterine muscles. Afterpains usually decrease to mild discomfort by the 3rd day postpartum (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Nursing Considerations

Analgesics are frequently used to lessen the discomfort of afterpains. Most commonly prescribed analgesics may be used for short-term pain relief without harm to the infant. The benefits of pain relief, such as comfort and relaxation, facilitate the milk-ejection reflex or letdown reflex, the release of milk from the alveoli into the ducts. These benefits usually outweigh the small effects of the medication on the infant.

Some mothers find that lying in a prone position with a small pillow or folded blanket under the abdomen helps keep the uterus contracted and provides relief. Afterpains are self-limited and decrease rapidly after 48 hours.

Lochia

Changes in the color and amount of lochia also provide information about whether involution is progressing normally.

Changes in Color

For the first 3 days after childbirth, lochia consists almost entirely of blood, with small particles of decidua and mucus. Because of its reddish or red-brown color, it is called lochia rubra. The amount of blood decreases by about the 4th day, and the color of lochia changes from red to pink or brown-tinged (lochia serosa). Lochia serosa is composed of serous exudate, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and cervical mucus. By about the 11th day, the erythrocyte component decreases. The discharge becomes white, cream, or light yellow in color (lochia alba). Lochia alba contains leukocytes, decidual cells, epithelial cells, fat, cervical mucus, and bacteria. It is present in most women until the 3rd week after childbirth but may persist until the 6th week (Whitmer, 2011). Table 20-1 summarizes the characteristics of normal and abnormal lochia.

TABLE 20-1

| TIME AND TYPE | NORMAL DISCHARGE | ABNORMAL DISCHARGE |

| Days 1-3: lochia rubra | Bloody; small clots; fleshy, earthy odor, red or red/brown | Large clots; saturated perineal pads; foul odor |

| Days 4-10: lochia serosa | Decreased amount; serosanguineous; pink or brown-tinged | Excessive amount; foul smell; continued or recurrent reddish color |

| Days 11-21: lochia alba (may last until 6th week postpartum) | Further decreased amounts; white, cream, or light yellow | Persistent lochia serosa; return to lochia rubra, foul odor; discharge continuing |

Amount

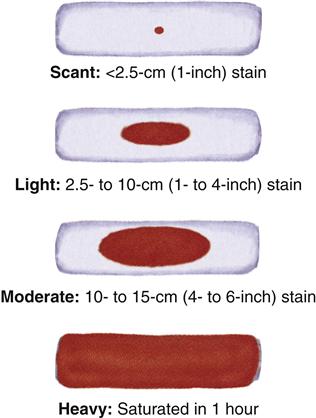

Because estimating the amount of lochia on a peripad (perineal pad) is difficult, nurses frequently record lochia in terms that are difficult to quantify, such as “scant,” “moderate,” and “heavy.” One method for estimating the amount of lochia in 1 hour uses the following labels (Whitmer, 2011):

Scant: Less than a 2.5-cm (1-inch) stain on the perineal pad

Light: 2.5- to 10-cm (1- to 4-inch) stain

Moderate: 10- to 15-cm (4- to 6-inch) stain

Determining the time the peripad has been in place is important in assessing lochia. What appears to be a light flow may actually be a moderate flow if the peripad has been in use less than an hour (Figure 20-2).

Lochia is less for women who had a cesarean birth because some of the endometrial lining is removed during surgery. The lochia will go through the same phases as that of the woman with a vaginal birth, but the amount will be less. Lochia is often heavier when the new mother first gets out of bed, because gravity allows blood that has pooled in the vagina during the hours of rest to flow freely when she stands.

Cervix

Immediately after childbirth the cervix is formless, flabby, and open wide. Small tears or lacerations may be present, and the cervix is often edematous. Healing occurs rapidly, and by the end of the 1st week the cervix feels firm, and the external os is dilated 1 cm (Whitmer, 2011). The internal os closes as before pregnancy, but the shape of the external os is permanently changed. It remains slightly open and appears slit-like rather than round, as in the nulliparous woman.

Vagina

Soon after childbirth the vaginal walls appear edematous, and multiple small lacerations may be present. Very few vaginal rugae (folds) are present. The hymen is permanently torn and heals with small, irregular tags of tissue visible at the vaginal introitus.

Although the rugae are regained by 3 to 4 weeks, it takes 6 to 10 weeks for the vagina to complete involution and to gain approximately the same size and contour it had before pregnancy. The vagina does not entirely regain the nulliparous size, however (Blackburn, 2013).

During the postpartum period, vaginal mucosa becomes atrophic, and vaginal walls do not regain their thickness until estrogen production by the ovaries is reestablished. Because ovarian function, and therefore estrogen production, is not well established during lactation, breastfeeding mothers are likely to experience vaginal dryness and may experience dyspareunia (discomfort during intercourse).

Perineum

Because of pressure from the fetal head, the muscles of the pelvic floor stretch and thin greatly during the second stage of labor. After childbirth the perineum may be edematous and bruised. Some women have a surgical incision (episiotomy) of the perineal area to enlarge the opening for birth. Initial healing of the episiotomy site occurs in 2 to 3 weeks, but complete healing may take 4 to 6 months (Blackburn, 2013). Lacerations of the perineum also may occur during delivery. Lacerations and episiotomies are classified according to tissue involved (Box 20-1). (See episiotomy discussion in Chapter 19, p. 423.)

Discomfort

Although the episiotomy is relatively small, the muscles of the perineum are involved in many activities (walking, sitting, stooping, squatting, bending, urinating, and defecating). An incision or laceration in this area can cause a great deal of discomfort. In addition, many pregnant women are affected by hemorrhoids (distended rectal veins), which are pushed out of the rectum during the second stage of labor.

Nursing Considerations

Hemorrhoids, as well as perineal trauma, episiotomy, or lacerations, can make physical activity or bowel elimination difficult during the postpartum period. Relief of perineal discomfort is a nursing priority and includes teaching self-care measures, such as applying ice, performing perineal care, using topical anesthetics, and taking ordered analgesics.

Cardiovascular System

Hypervolemia, which produces as much as a 45% increase in blood volume at term, allows the woman to tolerate a substantial blood loss during childbirth without ill effect (Jones, 2009). On the average, up to 500 mL of blood is lost in vaginal deliveries, and 1000 mL is lost in cesarean births (Blackburn, 2013).

Cardiac Output

Despite the blood loss, a transient increase in maternal cardiac output occurs after childbirth. This increase is caused by (1) an increased flow of blood back to the heart when blood from the uteroplacental unit returns to the central circulation, (2) decreased pressure from the pregnant uterus on the vessels, and (3) the mobilization of excess extracellular fluid into the vascular compartment. The cardiac output returns to prelabor values within an hour after delivery. Gradually, cardiac output decreases and returns to prepregnancy levels by 6 to 12 weeks after childbirth (Blackburn, 2013).

Plasma Volume

The body rids itself of excess plasma volume needed during pregnancy by diuresis and diaphoresis:

• Diuresis (increased excretion of urine) is facilitated by a decline in the adrenal hormone aldosterone, which increases during pregnancy to counteract the salt-wasting effect of progesterone. As aldosterone production decreases, sodium retention declines and fluid excretion accelerates. A decrease in oxytocin, which promotes reabsorption of fluid, also contributes to diuresis. A urinary output of up to 3000 mL/day is common, especially on days 2 through 5 of the postpartum period (Blackburn, 2013).

Blood Values

Several components of the blood change during the postpartum period. Marked leukocytosis occurs, with the white blood cell (WBC) count increasing to as high as 30,000/mm3 during labor and the immediate postpartum period. The average range is 14,000 to 16,000/mm3 (Cunningham et al., 2010). The WBC falls to normal values by 6 days after birth (Blackburn, 2013).

Maternal hemoglobin and hematocrit values are difficult to interpret during the first few days after birth because of the remobilization and rapid excretion of excess body fluid. The hematocrit is low when plasma increases and dilutes the concentration of blood cells and other substances carried by the plasma. As excess fluid is excreted, the dilution is gradually reduced. The hematocrit returns to normal values within 4 to 6 weeks unless excessive blood loss has occurred (Blackburn, 2013).

Coagulation

During pregnancy, plasma fibrinogen and other factors necessary for coagulation increase. As a result, the mother’s body has a greater ability to form clots and thus prevent excessive bleeding. Fibrinolytic activity (ability to break down clots) is decreased during pregnancy. Although fibrinolysis increases shortly after delivery, elevations in clotting factors continue for several days or longer, causing a continued risk of thrombus formation. It takes 4 to 6 weeks before the hemostasis returns to normal prepregnant levels (Blackburn, 2013).

Although the incidence of thrombophlebitis has declined greatly as a result of early postpartum ambulation, new mothers are still at increased risk (see Chapter 28). Women who have varicose veins, a history of thrombophlebitis, or a cesarean birth are at further risk, and the lower extremities should be monitored closely. Pneumatic compression devices should be applied before cesarean delivery for all women not already receiving anticoagulants (American College of Obstetricians, 2011). A national voluntary standard for perinatal care is that all women having a cesarean birth have prophylaxis with heparin or pneumatic compression devices (National Quality Forum, 2009).

Gastrointestinal System

Soon after childbirth, digestion begins to be active and the new mother is usually hungry because of the energy expended in labor. She is also thirsty because of the decreased intake during labor and the fluid loss from exertion, mouth breathing, and early diaphoresis. Nurses anticipate the mother’s needs and provide food and fluids soon after childbirth.

Constipation is a common problem during the postpartum period for a variety of reasons. Bowel tone and intestinal motility, which were diminished during pregnancy as a result of progesterone, remain sluggish for several days. The abdominal musculature is relaxed. Decreased food and fluid intake during labor may result in small, hard stools. Perineal trauma, episiotomy, and hemorrhoids cause discomfort and interfere with effective bowel elimination. In addition, many women anticipate pain when they attempt to defecate and are unwilling to exert pressure on the perineum.

Temporary constipation is not harmful, although it can cause a feeling of abdominal fullness and flatulence. Stool softeners and laxatives are frequently prescribed to prevent or treat constipation. The first stool usually occurs within 2 to 3 days postpartum. Normal patterns of bowel elimination usually resume by 8 to 14 days after birth (Blackburn, 2013).

Urinary System

During childbirth, the urethra, bladder, and tissue around the urinary meatus may become edematous and traumatized as the fetal head passes beneath the bladder. This condition often results in diminished sensitivity to fluid pressure, and many new mothers have no sensation of needing to void even when the bladder is distended.

The bladder fills rapidly because of the diuresis that follows childbirth. As a consequence, the mother is at risk for overdistention of the bladder, incomplete emptying of the bladder, and retention of residual urine. Women who have received regional anesthesia are at particular risk for bladder distention and for difficulty voiding until feeling returns.

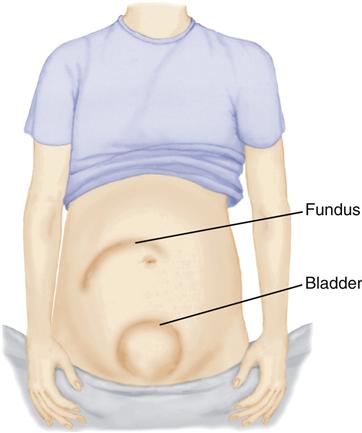

Urinary retention and overdistention of the bladder may cause urinary tract infection and increased postpartum bleeding. Urinary tract infection occurs when urinary stasis allows time for bacteria to multiply. Bleeding may increase because the uterine ligaments, which were stretched during pregnancy, allow the uterus to be displaced upward and laterally by the full bladder. The displacement results in decreased uterine muscle contraction (uterine atony), a primary cause of excessive bleeding (Figure 20-3).

Stress incontinence may begin during pregnancy or during the postpartum. It usually improves within 3 months after birth (James, 2008). For some women, the problem resolves with pelvic floor exercises and time for healing. Others may have continued problems (see Chapter 32).

The dilation of the ureters and kidney pelvis improves by the end of the first week. The structures generally regain their nonpregnant state by 2 to 8 weeks after delivery (Cunningham et al., 2010). Both protein and acetone may be present in the urine in the first few postpartum days. Acetone suggests dehydration, which may occur during the exertion of labor. Mild proteinuria is usually the result of the catabolic processes involved in uterine involution.

Musculoskeletal System

Muscles and Joints

In the first 1 to 2 days after childbirth, many women experience muscle fatigue and aches, particularly of the shoulders, neck, and arms, because of the effort of labor. Warmth and gentle massage increase circulation to the area and provide comfort and relaxation.

During the first few days, levels of the hormone relaxin gradually subside and the ligaments and cartilage of the pelvis begin to return to their prepregnancy positions. These changes can cause hip or joint pain that interferes with ambulation and exercise. The mother should be told that the discomfort is temporary and does not indicate a medical problem. Correct posture and good body mechanics are extremely important during this time to help prevent low back pain and injury to the joints (see Figures 13-10 and 13-11).

Abdominal Wall

During pregnancy, the abdominal walls stretch to accommodate the growing fetus, and muscle tone is diminished. Many women, expecting the abdominal muscles to return to the prepregnancy condition immediately after childbirth, are dismayed to find the abdominal muscles weak, soft, and flabby.

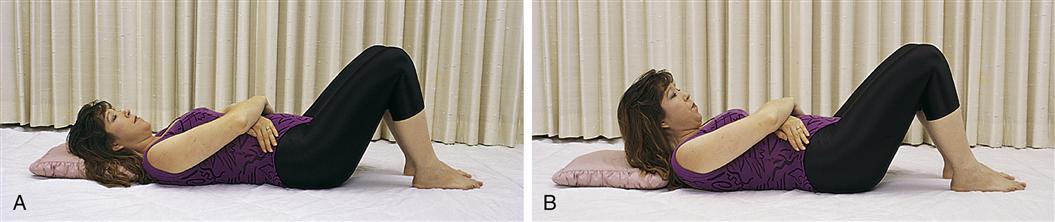

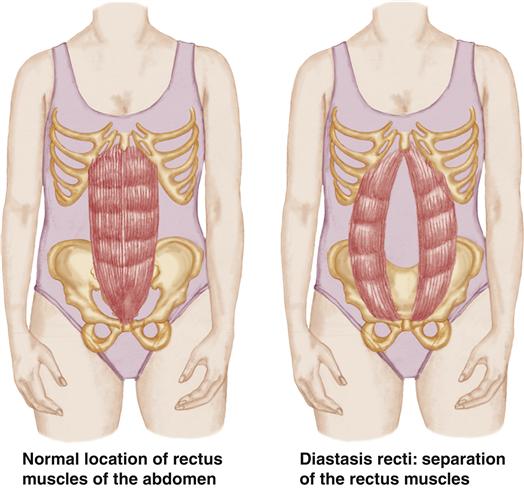

The longitudinal muscles of the abdomen may separate (diastasis recti) during pregnancy (Figure 20-4). The separation may be minimal or severe. The mother may benefit from gentle exercises (Figure 20-5) to strengthen the abdominal wall. The diastasis usually resolves within 6 weeks (Whitmer, 2011).

Integumentary System

Many skin changes that occur during pregnancy are caused by an increase in hormones. When the hormone levels decline after childbirth, the skin gradually reverts to the nonpregnant state. For example, estrogen, progesterone, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone, which caused hyperpigmentation during pregnancy, decrease rapidly after childbirth and pigmentation begins to recede. This change is particularly noticeable when melasma (mask of pregnancy) and linea nigra fade and disappear for most women.

Striae gravidarum (stretch marks), which develop during pregnancy when connective tissues in the abdomen and breasts are stretched, gradually fade to silvery lines but do not disappear.

Loss of hair may especially concern the woman. This is a normal response to the hormonal changes that caused decreased hair loss during pregnancy. Hair loss begins at 4 to 20 weeks after delivery and is regrown in 4 to 6 months for two thirds of women and by 15 months for the rest (Blackburn, 2013).

Neurologic System

Many women experience discomfort and fatigue after childbirth. Afterpains, discomfort from episiotomy, lacerations, incisions, muscle aches, and breast engorgement (swelling from increased blood flow, edema, and presence of milk) may contribute to a woman’s discomfort and inability to sleep. Anesthesia or analgesia may produce temporary neurologic changes such as lack of feeling in the legs and dizziness. During this time, prevention of injury that could occur as a result of falling is a priority.

Complaints of headache need careful assessment. Bilateral and frontal headaches are common in the first postpartum week and may be a result of changes in fluid and electrolyte balance (Blackburn, 2013). Although they are uncommon, spinal headaches after spinal anesthesia may occur. They may be most severe when the woman is in an upright position and are relieved by a supine position. They should be reported to the appropriate health care provider, usually an anesthesiologist (see Chapter 18). Headache, proteinuria, blurred vision, photophobia, and abdominal pain may indicate development or worsening of preeclampsia (see Chapter 25).

Pain continues after discharge. Mothers report being surprised at the amount of pain they experienced when they went home. Some mothers feel that pain interferes with their ability to care for themselves and their infants (Declercq, Cunningham, Johnson, et al., 2008).

Endocrine System

After expulsion of the placenta, a fairly rapid decline occurs in placental hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and human placental lactogen. Human chorionic gonadotropin is present for 3 to 4 weeks. If the mother is not breastfeeding, the pituitary hormone prolactin, which stimulates milk secretion, returns to nonpregnant levels in 14 days (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011).

Resumption of Ovulation and Menstruation

Although the first few cycles for both lactating and non-lactating women are often anovulatory, ovulation may occur before the first menses (Whitmer, 2011). For some women, ovulation resumes as early as 3 weeks postpartum (Cunningham et al., 2010). Therefore contraceptive measures are important considerations when sexual relations are resumed for both lactating and non-lactating women (see Chapter 31).

Approximately 40% to 45% of non-nursing mothers resume menstruation at 6 to 8 weeks after childbirth, 75% by 12 weeks, and all within 6 months. Menses while lactating may resume as early as 8 weeks or as late as 18 months (Whitmer, 2011). Frequent breastfeeding with no supplements is more likely to delay menses, but menses and ovulation are increasingly likely after the infant is 6 months old.

Lactation

During pregnancy, estrogen and progesterone prepare the breasts for lactation. Although prolactin also rises during pregnancy, lactation is inhibited at this time by the high level of estrogen and progesterone. After expulsion of the placenta, estrogen and progesterone decline rapidly, and prolactin initiates milk production within 2 to 3 days after childbirth. Once milk production is established, it continues because of frequent removal of milk from the breast.

Oxytocin is necessary for milk ejection, or “letdown.” Oxytocin causes milk to be expressed from the alveoli into the lactiferous ducts during suckling (see Chapter 23).

Weight Loss

Approximately 5.5 kg (12 lb) is lost during childbirth. This includes the weight of the fetus, placenta, amniotic fluid, and blood lost during the birth. An additional 4 kg (9 lb) over the next 2 weeks and another 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) are lost by 6 months after delivery (Cunningham et al., 2010). Adipose (fatty) tissue that was gained during pregnancy to meet the energy requirements of labor and breastfeeding is not lost initially, and the usual rate of loss is slow. Younger women with lower prepregnancy weight and lower parity lose weight sooner and faster (Blackburn, 2013).

Many women do not lose all the weight gain and retain an average of 1 kg (2.2 lb) with each pregnancy (Blackburn, 2013). Women are often frustrated because they want to have an immediate return to prepregnancy weight. Nurses can provide information about diet and exercise that will produce an acceptable weight loss but does not deplete energy or impair the mother’s health (see Chapter 14).

Postpartum Assessments

Providing essential, cost-effective postpartum care to new families is a challenge for maternity nurses. Most women stay in the birth facility for 48 hours after a vaginal birth and 96 hours after a cesarean birth. Some choose to go home earlier, however.

Although the length of stay is short, the family’s need for care and information is extensive. This need causes nurses a great deal of concern for families who are discharged without adequate preparation or support.

Clinical Pathways

Some institutions use clinical pathways (also called critical pathways, care maps, care paths, or multidisciplinary action plans) to guide necessary care while reducing the length of stay. Clinical pathways identify expected outcomes and establish time frames for specific assessments and interventions that prepare the mother and infant for discharge. The clinical pathway is a guideline and documentation tool.

Initial Assessments

When caring for postpartum women, the nurse faces a high risk of contact with body fluids (colostrum, breast milk, and lochia from the mother as well as urine, stool, and blood from the infant). Therefore the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for standard blood and body fluid precautions must be followed diligently. Postpartum assessments begin during the fourth stage of labor (the first 1 to 2 hours after childbirth). During this time the mother is examined to determine whether she is physically stable. Initial assessments include:

Chart Review

When the initial assessments confirm the mother’s physical condition is stable, nurses should review the chart to obtain pertinent information and determine if there are factors that increase the risk of complications during the postpartum period. Relevant information includes:

• Time and type of delivery (use of vacuum extractor, forceps)

• Presence and degree of episiotomy or lacerations

• Anesthesia or medications administered

• Significant medical and surgical history, such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease

• Medications given during labor and delivery or routinely taken and reasons for their use

• Chosen method of infant feeding

Laboratory data are also examined. Of particular interest are the prenatal hemoglobin and hematocrit values, the blood type and Rh factor, hepatitis B surface antigen, rubella immune status, syphilis screen, and group B streptococcus status.

Need for Rho(D) Immune Globulin

Prenatal and neonatal records are checked to determine whether Rho(D) immune globulin should be administered. Rho(D) immune globulin may be necessary if the mother is Rh negative, the newborn is Rh positive, and the mother is not already sensitized. To prevent the development of maternal antibodies that would affect subsequent pregnancies, Rho(D) immune globulin should be administered within 72 hours after childbirth (see Chapter 25).

Need for Vaccines

Rubella Vaccine

A prenatal rubella antibody screen is performed on each pregnant woman to determine if she is immune to rubella. If she is not immune, rubella vaccine is recommended after childbirth to prevent her from acquiring rubella during subsequent pregnancies, when it can cause serious fetal anomalies. Although there is no evidence of fetal damage when the vaccine was inadvertently given to pregnant women, there is a theoretical risk of defects because rubella vaccine contains live virus. Therefore, women are advised not to become pregnant for at least 28 days after receiving rubella vaccine (Atkinson, Wolfe, Hamborsky, et al., 2009).

Before administration, some agencies require that a woman sign a statement giving permission to be given the vaccine and indicating that she understands the risks of becoming pregnant again too soon after the injection (see Drug Guide). If this statement is not required, the nurse should record in the chart that the risk has been explained and the woman has verbalized understanding.

Pertussis Vaccine

Recent outbreaks of pertussis have had serious effects in infants and young children. Although most

adults have been vaccinated as children, the effectiveness fades with time. Full protection of vaccinated infants does not occur until the entire series is completed.

The CDC (2010) recommends that all adults in contact with infants and young children get a booster dose of pertussis vaccine. The vaccine may be offered to women before hospital discharge after childbirth.

Risk Factors for Hemorrhage and Infection

Nurses must be aware of conditions that increase the risk of hemorrhage and infection, the two most common complications of the puerperium.

Focused Assessments after Vaginal Birth

Nurses perform postpartum assessments according to facility protocol. For example, a protocol might require assessment every 15 minutes for the first hour, every half hour for the next hour, every 4 hours for the first 24 hours, and every 8 hours thereafter. Of course, assessments are performed more frequently if findings are abnormal.

Although assessments vary according to particular problems presented, a focused assessment for a vaginal delivery generally includes the vital signs, fundus, lochia, perineum, bladder elimination, breasts, and lower extremities. The assessment for post-cesarean mothers is more extensive (see p. 445).

Vital Signs

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure (BP) varies with position and the arm used. To obtain accurate results, the BP should be measured on the same arm with the mother in the same position each time. Postpartum BP should be compared with that of the predelivery period so that deviations from what is normal for the mother can be quickly identified. An increase from the baseline may be caused by pain or anxiety. If the BP is 140/90 mm Hg or higher, preeclampsia may be present. A decrease may indicate dehydration or hypovolemia resulting from excessive bleeding.

Orthostatic Hypotension

After birth, a rapid decrease in intraabdominal pressure results in dilation of blood vessels supplying the viscera. The resulting engorgement of abdominal blood vessels contributes to a rapid fall in BP of 15 to 20 mm Hg when the woman moves from a recumbent to a sitting position. This change causes mothers to feel dizzy or lightheaded or to faint when they stand. The nursing diagnosis Risk for Injury applies to women with orthostatic hypotension (see Nursing Care Plan: Postpartum Hypotension, Fatigue, and Pain, p. 447).

Hypotension may also indicate hypovolemia. Careful assessments for hemorrhage (location and firmness of the fundus, amount of lochia, pulse rate for tachycardia) should be made if the postpartum BP is significantly less than the prenatal baseline blood pressure.

Pulse

Bradycardia, defined as a pulse rate of 40 to 50 beats per minute (bpm) may occur in some women (James, 2008). The lower pulse rate may reflect the large amount of blood that returns to the central circulation after delivery of the placenta. The increase in central circulation results in increased stroke volume and allows a slower heart rate to provide adequate maternal circulation.

Tachycardia may indicate pain, excitement, fatigue, dehydration, hypovolemia, anemia, or infection. If tachycardia is noted, additional assessments should include BP, location and firmness of the uterus, amount of lochia, estimated blood loss at delivery, and hemoglobin and hematocrit values. The objective of the additional assessments is to rule out excessive bleeding and to intervene at once if hemorrhage is suspected.

Respirations

A normal respiratory rate of 12 to 20 breaths per minute should be maintained. Assessing breath sounds is especially important for mothers who have a cesarean birth, are smokers, have a history of frequent or recent upper respiratory infections or asthma, and for those receiving magnesium sulfate (see Chapter 25).

Temperature

A temperature of up to 38° C (100.4° F) is common during the first 24 hours after childbirth and may be caused by dehydration or normal postpartum leukocytosis. If the elevated temperature persists for longer than 24 hours or if it exceeds 38° C (100.4° F) or the woman shows other signs of infection the nurse should report it to the physician or nurse-midwife (see Chapter 28).

Pain

Pain, the fifth vital sign, should be assessed to determine the type, location, and severity on a pain scale. Nurses must remain alert to signs of afterpains, perineal discomfort, and breast tenderness. Nonspecific signs of discomfort include an inability to relax or sleep, a change in vital signs, restlessness, irritability, and facial grimaces. The nurse should encourage women to take prescribed medications as needed and should evaluate the effectiveness of pain-relief measures.

Fundus

The fundus should be assessed for consistency and location. It should be firmly contracted and at or near the level of the umbilicus. If the uterus is above the expected level or shifted (usually to the right) from the middle of the abdomen (midline position), the bladder may be distended. The location of the fundus should be rechecked after the woman has emptied her bladder.

If the fundus is difficult to locate or is soft or “boggy,” the nurse stimulates the uterine muscle to contract by gently massaging the uterus. The nondominant hand must support and anchor the lower uterine segment if it is necessary to massage an uncontracted uterus. Uterine massage is not necessary if the uterus is firmly contracted.

The uterus can contract only if it is free of intrauterine clots. To expel clots, the nurse must first massage the fundus until it is firmly contracted. The nurse then supports the lower uterine segment, as illustrated in the Procedure: Assessing the Uterine Fundus. This support prevents inversion of the uterus (turning inside out) when the nurse applies firm pressure downward toward the vagina to express clots that have collected in the uterus. Nurses should observe the perineum for the number and size of clots expelled. If lochia is excessive or large clots are present, they should be weighed to estimate amount (see Chapter 28). Table 20-2 describes normal and abnormal findings of the uterine fundus and includes follow-up nursing actions for abnormal findings.

TABLE 20-2

OBSERVATIONS OF THE UTERINE FUNDUS AND NURSING ACTIONS

| NORMAL FINDINGS | ABNORMAL FINDINGS | NURSING ACTIONS |

| Fundus firmly contracted. | Fundus soft, “boggy,” uncontracted, or difficult to locate. | Support lower uterine segment. Massage until firm. |

| Fundus remains contracted when massage is discontinued. | Fundus becomes soft and uncontracted when massage is stopped. | Continue to support lower uterine segment. Massage fundus until firm, then apply pressure to express clots that may be accumulating in uterus. Notify health care provider and begin oxytocin administration, as prescribed, to maintain a firm fundus. |

| Fundus located at level of umbilicus and midline. | Fundus above umbilicus and/or displaced from midline. | Assess bladder elimination. Assist mother in urinating or catheterize, if necessary. Recheck the position and consistency of fundus after bladder is empty. |

Drugs are sometimes needed to maintain contraction of the uterus and thus to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. The most commonly used drug is oxytocin (Pitocin) (see Drug Guide for oxytocin, Chapter 19, p. 417).

Lochia

Important assessments include the amount, color, and odor of lochia. Nurses observe the lochia on perineal pads and while checking the perineum. They also assess vaginal discharge while palpating or massaging the fundus to determine the amount of lochia and the number and size of any clots expressed during these procedures. Important guidelines include:

The odor of lochia is usually described as “fleshy,” “earthy,” or “musty.” A foul odor suggests endometrial infection, and assessments should be made for additional signs of infection. These signs include maternal fever, tachycardia, uterine tenderness, and pain.

Absence of lochia, like the presence of a foul odor, may also indicate infection. If the birth was cesarean, lochia may be scant because some of the endometrial lining was removed. Lochia should not, however, be entirely absent.

Perineum

The acronym REEDA is used as a reminder that the site of an episiotomy or a perineal laceration should be assessed for five signs: redness (R), edema (E), ecchymosis (bruising) (E), discharge (D), and approximation (the edges of the wound should be closed, as though stuck or glued together) (A).

Redness of the wound may indicate the usual inflammatory response to injury. If accompanied by excessive pain or tenderness, however, it may indicate the beginning of localized infection. Ecchymosis or edema indicates soft tissue damage that can delay healing. There should be no discharge from the wound. Rapid healing requires that the edges of the wound be closely approximated (Procedure: Assessing the Perineum).

Bladder Elimination

During the early postpartum period women may not experience the urge to void even if the bladder is full. Nurses must rely on physical assessment to determine whether the bladder is distended. Bladder distention often produces an obvious or palpable bulge that feels like a soft, movable mass above the symphysis pubis. Other signs include an upward and lateral displacement of the uterine fundus and increased lochia. Frequent voidings of less than 150 mL suggest urinary retention with overflow. Signs of an empty bladder include a firm fundus in the midline and a nonpalpable bladder.

Two or three voidings should be measured after birth or the removal of a catheter to determine if normal bladder function has returned. When the mother can void 300 to 400 mL, the bladder is usually empty. Regardless of the amount voided, however, the fundus must be assessed after the woman voids to confirm that the bladder is empty. Subjective symptoms of urgency, frequency, or dysuria suggest urinary tract infection and should be reported to the health care provider.

Breasts

For the first day or two after delivery, the breasts should be soft and nontender. After that, breast changes depend largely on whether the mother is breastfeeding. The breasts should be examined even if she chooses formula feeding because engorgement may occur. The size, symmetry, and shape of the breasts should be observed. The skin should be inspected for dimpling or thickening, which, although rare, can indicate a breast tumor.

The areola and nipple should be carefully examined for problems such as flat or retracted nipples, which may make breastfeeding more difficult. Signs of nipple trauma (redness, blisters, fissures) may be present during the first days of breastfeeding, especially if the mother needs assistance in positioning the infant correctly (see Chapter 23).

The breasts should be palpated for firmness and tenderness, which indicate increased vascular and lymphatic circulation that may precede milk production. The breasts may feel “lumpy” as various lobes begin to produce milk.

The breast assessment is an excellent opportunity to provide information or reassurance about breast care and breastfeeding techniques. The mother should be taught how to assess her own breasts so she can continue after discharge.

Lower Extremities

The legs are examined for varicosities and signs or symptoms of thrombophlebitis. Indications of thrombophlebitis include localized areas of redness, heat, edema, and tenderness. Pedal pulses may be obstructed by thrombophlebitis and should be palpated with each assessment (see Chapter 28).

Homans Sign

Discomfort in the calf with passive dorsiflexion of the foot is a positive Homans sign and may indicate deep vein thrombosis. A negative Homans sign is indicated by absence of discomfort. A positive Homans sign should be reported to the health care provider, along with redness, tenderness, or warmth of the leg. Assessment of Homans sign can be confusing because a deep venous thrombosis may not produce calf pain with dorsiflexion. In addition, women may report pain that is caused by strained muscles from positioning and pushing during delivery.

Edema and Deep Tendon Reflexes

Pedal or pretibial edema may be present for the first few days, until excess interstitial fluid is remobilized and excreted. Diuresis is highest between the 2nd and 5th days after birth (Blackburn, 2013).

Deep tendon reflexes should be 1+ to 2+. Report brisker than average and hyperactive reflexes (3+ to 4+), which suggest preeclampsia. (See p. 596 for a description of assessing deep tendon reflexes.)

Care in the Immediate Postpartum Period

The postpartum period is often divided into three periods. The first 24 hours is the immediate postpartum period; the 1st week is the early postpartum period; and the 2nd week through the 6th week is the late postpartum period. Care of the mother during the immediate postpartum period focuses on physiologic safety, comfort measures, bladder elimination, and health education.

Providing Comfort Measures

Ice Packs

Ice causes vasoconstriction and is most effective if applied soon after the birth to prevent edema and numb the perineum. Chemical ice packs and plastic bags or nonlatex gloves filled with ice may be used during the first 12 to 24 hours after a vaginal birth. The ice pack is wrapped in a washcloth or paper before it is applied to the perineum. It should be left in place until the ice melts. It is then removed for 10 minutes before a fresh pack is applied. Some peripads have cold packs in them. Condensation from ice may dilute lochia and make it appear heavier than it actually is.

Sitz Baths

Sitz baths are used in some agencies to cleanse and comfort the traumatized perineum. Cool water may be used during the first 24 hours to reduce pain from edema. Warm water increases circulation and promotes healing and may be most effective after 24 hours. Nurses must place the emergency bell within easy reach in case the mother feels faint during the sitz bath. The woman often takes the disposable sitz bath container home. She should clean it well between uses.

Perineal Care

Perineal care consists of squirting warm water over the perineum after each voiding or bowel movement. This is important for all postpartum women whether the birth was vaginal or by cesarean. The bottle should not touch the perineum. Perineal care cleanses, provides comfort, and prevents infection. The perineum is gently patted rather than wiped dry.

Topical Medications

Anesthetic sprays decrease surface discomfort and allow more comfortable ambulation. The mother is instructed to hold the nozzle of the spray 6 to 12 inches from her body and direct it toward the perineum. The spray should be used after perineal care and before clean pads are applied. Astringent compresses should be placed directly over the hemorrhoids to relieve pain. Hydrocortisone ointments may also be applied over the hemorrhoids to increase comfort.

Sitting Measures

The mother should be advised to squeeze her buttocks together before sitting and to lower her weight slowly onto her buttocks. This measure prevents stretching of the perineal tissue and avoids sharp impact on the traumatized area. Sitting slightly to the side is helpful to prevent the full weight from resting on the episiotomy site.

Analgesics

Mothers should be encouraged to take prescribed medications for afterpains and perineal discomfort. Many analgesics are combinations that include acetaminophen. The nurse should be careful that the woman receives no more than 4 g of acetaminophen in a 24-hour period. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, are frequently prescribed for their antiinflammatory properties. They can be given along with other analgesics.

Promoting Bladder Elimination

Many new mothers have difficulty voiding because of edema and trauma of the perineum and diminished sensitivity to fluid pressure in the bladder. As soon as they are able to ambulate safely, mothers should be assisted to the bathroom. It is important to provide privacy and to allow adequate time for the first voiding. Common measures to promote relaxation of the perineal muscles and to stimulate the sensation of needing to void include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree