Chapter 7 Planning public health strategies

Introduction

Until fairly recently, health policy in the UK was thought to be about how the health service is funded and the provision of medical care. Health is not just the realm of the health service, but engages all sectors of the society, government administration and the globalisation of the economy. The inter-relationships of all these factors play a part in both individual and population health. Changes in philosophy that have occurred within past few years acknowledge that it is not just the individual state of good or bad health that decides human survival, but also the social determinants of health (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003).

Health strategy

The broad-based NHS strategies are set by government and are based on party ideologies and what the electorate has mandated. The past few years have seen a plethora of policy changes that have centred on the community, with the focus being on public health, partnerships and public participation.

Proposals for reconfiguration are underway for the possibility for primary care trusts (PCTs) to take on the responsibility for commissioning and securing services from a range of providers. Therefore, some of the traditional community services that were provided by PCTs can be provided by other organisations, including the independent and voluntary sector (Department of Health (DH) 2005a). Accordingly:

Practice-based commissioning

Wanless (2002) looked at future funding models for the NHS and suggested that health needs should be focused on health promotion and disease prevention, and that generalising of National Service Frameworks for other diseases could cost less than anticipated. However, the report also says that development not considered to be cost effective should be abandoned.

Part of the challenge within the NHS is that services are reorganised in terms of the political ideologies and many decisions about resources need to be made for the long term; for example, the number of people to be trained, the skills they will require, the types of buildings likely to be needed and the information and communication technologies upon which the efficient operation of the system will depend (Wanless 2002).

Policy context

The Health Act 1999 mandated an emphasis on promoting health, reducing inequalities and social exclusion, working in partnership and involving communities. saving lives: our healthier nation (Secretary of State for Health 1999) and reducing health inequalities (DH 1999a) built on the previous requirements under The Health of the Nation (DH 1992) targets. Providers are expected to take action on health targets at all levels, including the PCTs (DH 1997, 1998). Strategic Health Authorities are responsible for giving guidance and performance monitoring of the PCTs (England) on the national plan for the NHS (The NHS Plan) and National Service Frameworks. Explicit targets and objectives will be met by all PCTs and objectives carried out strategically. In the hierarchy of responsibilities, each unit of the organisation will adjust its focus to meet the national priorities. National priorities are based on people making healthier choices (DH 2005b). The six health priorities are:

Each health authority is obliged to produce a Health Improvement and Modernisation Plan to set the strategic framework for improving health, reducing inequalities and offering faster, more responsive services of a consistently high standard (DH 2002).

Local Strategic Plans and Local Delivery Plans

Inclusiveness will be sought through the widest possible involvement in planning from the outset, rather than consultation on a near final product.

The Scottish Executive strategy includes six priority areas:

Both the New NHS – modern dependable (DH 1997) and Saving lives: our healthier nation (Secretary of State for Health 1999) stressed was user involvement in aspects in health. This area had been less well developed in the NHS but there were expectations that more work would be done to include what local people think about health and health services. The role of the users of health services became a priority in the NHS reforms in The NHS Plan (DH 2000).

The NHS is a huge and complex organisation employing large numbers of people, many of whom are from professional groups and in particular nursing. Nurses are the largest professional workforce in the NHS and responsible for a majority of the care delivered within the NHS. Health care is also administered through the independent and voluntary sectors, both of which may have contracts with the NHS or work at the interface between their respect-ive organisations in order to care for people who have health needs. Community nurses therefore play a major role in delivering care and liaising with nurse colleagues, and many other organisations, for and on behalf of their clients and patients. Whichever organisation delivers care, it does so within a structural framework through an overall health care plan. The difference between the institutional care and community care is the mode or plan of delivery. For community nursing and health visiting, access to other parts of the health care system entails knowledge of the local systems, good communication, liaison, and negotiating care with other providers, as well as an intimate knowledge of the individual needs. But changes are affecting the workforce and more than 25% of community nurses, health visitors and district nurses are aged over 50 years. There are 13 000 health visitors and approximately 2500 school nurses, compared with 40 000 social workers for children and families and 440 000 teachers. Employers need to encourage this group to stay in work as this will impact on the care of people in the community (Health Development Agency 2004).

Setting the context – public health

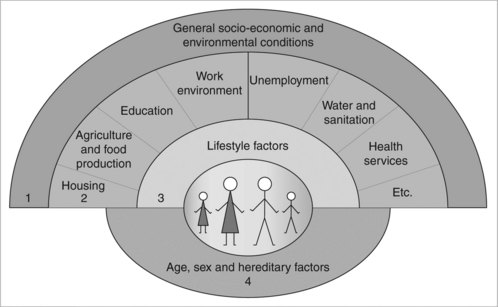

Public health is about the health of the local population. Its origins lie in economic, social, environmental and ecological aspects of health and disease. Public health is both a collective and an individual issue. The health of the population is affected by health-sustaining policies of other government departments that are responsible for agriculture and food production, the fiscal system and transport. Inequalities and health outcomes have as much to do with community and individual resources as with an individual’s genetic blueprint, and it is the reduction of health hazard that can help reduce the burden of disease. The wide range of these so-called ‘determinants of health’ is encapsulated in Dahlgren and Whitehead’s diagram, shown in Figure 7.1.

Health draws on wider influences outside the control of the NHS: the local authority, community groups, business and commerce and the media. They are inter-related and affect health and wellbeing (Taylor et al 2002).

Public health reports

In England, public health departments within PCTs are required to produce an annual Public Health Report, focusing on health priorities and local epidemi-ology. It includes comparative national and local district data, and information on the health services’ performance in relation to health targets set. Data from the Health Protection Agency are included in the report. It is a public document and, therefore, is open for scrutiny by the public. Public health departments take a population approach and measure health at different levels by age group, condition-specific groups and disease prevalence. PCTs are responsible for assessing the health needs locally and, therefore, need support to take on this wider role. The assessment of need might include participative techniques, such as rapid appraisal through key informants, and may commission other ad hoc studies. Each information source gives a different standpoint, but what is higher on the public health agenda is the user perspective. It has the purpose of ensuring the longer-term health planning and identification of unmet health needs. Health intelligence, therefore, involves the bigger picture of health, which is about not only how resources are used for health services, but also how the total community impacts on health (Pearson 1998).

Health needs assessment

Health needs assessment is a methodology that reviews population health issues in order to produce a set of recommendations for action to improve health outcomes. The interventions have to be realistically acceptable to the population and the priorities are usually those that can reduce health inequalities.

Community-based needs assessment

Community-based needs assessment has three main approaches: sociology, epidemiology and health economics (Billings & Cowley 1995). Biomedical models of health have been the most prominent features of medical and nursing education but it was the inclusion of social aspects of health and disease in health visiting and school nurse education that gave them specialised knowledge and skills of public health in a wider context. Poverty and deprivation in childhood have a major impact in the health of adults.

Needs assessment methods include the use of data and information to pre-sent a case for health improvement, service change or investment in a health programme. Much of the information gathered currently is used for the purpose of estimating total activity and total cost of services and really is an unsophisticated process for commissioning services. Careful consideration of community-based needs assessment is essential and should be carried out for an identified reason. According to research carried out by the London Health Economics Consortium (LHEC 1995), needs assessment has not had any major impact on purchasing decisions. The study found that purchasers and staff in primary and community services made a fairly accurate assessment of need in their local communities. But it did suggest that it may not be worthwhile going into detailed community enquiries, as needs may already have been identified by the local agencies. Local community nurses, in particular health visitors and school nurses, have long been required to produce community profiles, which have included a needs-based approach to their caseloads. What appear to be important in the process are: staff with good local knowledge of the area, good lines of communication and stable management structures within the organisation (LHEC 1995). Stable management structures do not appear to feature in the ever-changing policies.

Difference between need and want

To take a pragmatic view, need is about those things that are life sustaining, e.g. food, water, heat, shelter and health care. ‘Want’ may be a demand to have health and social care, which is felt to be a right in a modern society and which many older people may feel that they have invested in during their working lives. What may be more meaningful to ask is what people require. Requirements lie somewhere in between need and want, and may be about quality of the service (see also Chapter 13). It is a balance of competing demands and expectations. In the health services, users both need and want the good communications and staff to respond with respect to their human dignity, as often this is where users make value judgements of their care in terms of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. These are often related not so much to clinical interventions, but the way people are treated on a personal level (Stewart & Turner 1998, p. 142). Quality became a statutory duty for health service providers in the new NHS (DH 1998). Building on this, new standards for better health have now been set out, which must be met (DH 2004e). These are:

A strategy for health

What does a strategy involve? It is usually a corporate plan, which can be developed at a local or national level. Strategies can be developed to encompass a different size of area, or to focus on a specific topic or aspect of health. An example of a national level strategy focusing on one important aspect of health is the overall government strategy laid out in Every child matters: change for children (DfES 2004a), which is described in more detail in Chapter 4. This is a co-ordinated approach for the wellbeing of children and young people from birth to age 19 years. It includes the National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (NSF), which is a service specification that operates at a macro level, including all the elements required to meet the health needs for this part of the population.

The aim is for every child, whatever background or circumstances, to have the necessary support to:

Like all the NSFs, it was developed to tackle the fundamental issues of fragmentation, gaps and overlaps in the services that are delivered for children and young people. The contribution that community nursing and health visiting brings to this is vast, since they can offer so much to families in terms of identification of need, health promotion and prevention. However, a major concern for any strategy is the capacity of the workforce to meet the needs of children, young people and their families. By integration of the services and introducing core competencies for those working with the most vulnerable of children and young people, it is possible that practitioners can work across the boundaries of health and social care, allowing for more teaching and learning in a multidisciplinary setting. Shortages in the workforce have, in some cases, created opportunities for skill mix with the introduction of, for example, nursery nurses and child development workers into the local Sure Start programmes. There is a new statutory duty for local authorities that early years and child care will be part of an overall strategy as a result of the wider Every Child Matters agenda and the Children Act 2004 (HM Treasury 2004).

‘People will work in effective multi-disciplinary teams, be trained jointly to tackle cultural and professional divides, use a lead professional model where many disciplines are involved, and be co-located, often in extended schools or children’s centres’ Every Child Matters: Change for Children (See http://www.everychildmatters/gov.uk/aims/childrenstrusts/).

Integrated processes will support Children’s Trusts:

Community strategy for health improvement

A useful model for thinking about a strategy is the Seven ‘S’ Model (Pascale 1990), the use of which is illustrated in Box 7.1. Included in the model are hard ‘Ss’ – structure, strategy, and systems – and soft ‘Ss’ – staff, skills, style and shared values. Marsh and Macalpine (1995) say that nurses tend to focus more on the soft ‘Ss’, but need to develop skills and include the hard ‘Ss’.

Box 7.1

A community health strategy framework

Structure, strategy and systems

Local level

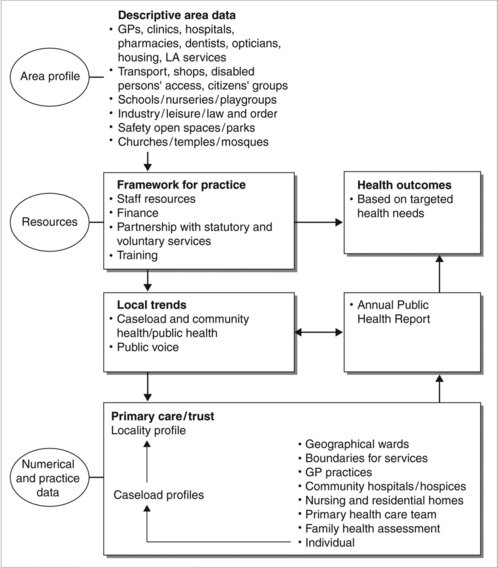

Community nurses, health visitors and allied health practitioners collect and hold both quantitative and qualitative information that is very live. The caseload analysis presents a picture of local need and outcomes of services accessed by clients or patients. It can have the advantage of informing the local practice, but how does this fit with locality need? The aggregation of data and profiles of the practices in a locality or for the PCT has a local intelligence function so that community nursing and health visiting resources can be estimated. Equally, by gathering information, levels of unmet need can be obtained. The involvement of ‘community matrons’ in identifying need is a public health approach and a model for case management (DH 2005c). The approach involves assessing not only people on the caseload, but the wider population.

The role of allied health professions is recognised as invaluable in the treatment and management for people with long-term medical conditions, particularly those living in the community. Patients can be taught: to become independent through rehabilitation, self-care and how they can prevent readmission to hospital (DH/Allied Health Professions 2005) (Figure 7.2).

Values in public health

The local authority and PCT/organisation must have a value system because it is accountable for the services that are commissioned and purchased on behalf of the local population. Central values are openness, fairness, equity, effectiveness, value for money and responsiveness (Ham et al 1993). Decisions have to be made on what the NHS will offer in terms of health care because resources are limited. Likewise, local authorities must make decisions through the democratic processes. Decisions made may be on the basis of clinical efficacy and information provided through NICE will be able to provide information about new drugs and technologies that have increased opportunities for better health, but which also bring dilemmas in decision making. Patients are much better informed of the possibilities and will wish to have any life-saving treatments offered by the NHS. Decisions, therefore, must be considered on the balance of clinical possibilities, outcome probabilities and quality of life. Sometimes decisions made are reasonable, but may be unpalatable for patients.

Health impact assessment

More recently, health impact assessment or environmental impact assessments have been carried out within communities where major modifications to land, buildings and services are occurring within a community. These may challenge the health and wellbeing of the local community. Environmental impact assessments have been mandatory under the EC regulation since 2001 and include any plans or programmes for agriculture, forestry, fisheries, water and waste management and town and country planning (EC 2001). Some of the changes can be major, such as building a new housing development, or relatively minor, such as closing a local health or facility. More local authorities are now requiring an impact assessment, which can include a health component. Normally, health impact assessments are carried out to identify positive and negative impacts of changes so the communities have a voice in the decisions made about their local neighbourhoods.

The principles that underlie health impact assessment are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree